RICHARD ROQUES

Between the two cities, London and Westminster, stood the mansions of the wealthiest of the aristocracy, rising from the river, accessible by land and water, ideally situated for commerce and court. Today there are still signs of these lost palaces hidden among the shops, railway stations and crowded streets of the twenty-first-century West End, but for most of the city’s history the space between the two cities was open land where people would come to hunt or for a breath of fresh air outside the foul, overcrowded walls of the medieval city.

Charing Cross and Trafalgar Square

STANDING OUTSIDE CHARING Cross railway station is the cross that gave this station its name. But things are not quite as they seem …

In 1290 Eleanor of Castille, the wife of Edward I, died in Harby in Lincoln and her body was brought to be buried in Westminster Abbey. At each of the twelve places that the funeral cortege rested on its way to London, a cross was erected in her memory. Two of these ‘Eleanor crosses’ were set up within the city, at Cornhill and at the village of Charing, the name of which means ‘to turn’, where the road turned away from the River Thames to head west.

The cortege had passed out of the old city of London through the gates at Temple Bar, past the heads on spikes (the heads boiled in salt to prevent birds pecking away at the features). Eleanor would have been glad to leave London: when she had been imprisoned in the Tower and had tried to escape she had been pelted with rubbish by Londoners. Now, Eleanor’s coffin moved down the Strand, with fields to the right and the river to the left, past the Savoy Palace, ever closer to her resting place. Durham House shielded the river from her sightless eyes and now the procession paused at the village of Charing.

A cluster of cottages stood here where the cross is today outside Charing Cross station. An ancient medieval cross outside a railway station … except the cross that stands here is the wrong cross in the wrong place. To find the site of the original Eleanor cross we need to walk a little further along the Strand to Trafalgar Square. Here is the original place the cross was located in the 1290s. The Square has vital significance for Londoners, in fact, as this is the dead centre of London. From here are all measurements calculated.

Here you’ll find a statue of Charles I, beheaded just a few minutes’ walk away in Whitehall on 30 January 1649. After Cromwell had abolished the monarchy he gave the statue, built in the 1630s by the Frenchman Hubert le Sueur, to John Rivett, a brazier. Rivett subsequently made a killing from the regicide by selling commemoration knives and forks he claimed were manufactured from the melted-down statue of the dead king. When Charles II was restored to the throne, however, he asked Rivett if he knew anything of the whereabouts of the statue of his father and it turned out that the brazier had hidden it in his garden. He returned it to Charles II, who was never so hypocritical as to admonish another conman. The fish shop that stood there was pulled down and the statue put on the spot of the original twelfth Eleanor cross. When the railway came to be built the Victorians named the station Charing Cross and asked Thomas Earp to build a replica of the cross, which they placed outside their terminus. So what you have today is a copy, and in the wrong place.

WHERE TO READ THIS

It has to be Gordon’s Wine Bar down the steps from Villiers Street. The river was not embanked until the 1850s and now this spot is a little park on land reclaimed from the Thames. Gordon’s Wine Bar has tables with large umbrellas where you can eat and drink, even in the rain. Also the balcony of Somerset House, with fabulous views of the South Bank and the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. There is a café with tables.

Villiers Street and Embankment

Down a narrow flight of steps off Villiers Street, by the side of the station, is Gordon’s Wine Bar, a fantastic old cellar. At the end of the tables is the water gate from the 1670s, now stranded a hundred yards away from the river. Built in elegant Portland stone, this was the entrance by water to the Duke of Buckingham’s mansion. Servants in rich livery would help you out of a gilded barge, through the stone archway into Buckingham House. The building is no longer here but the entrance by water remains.

Walking down the side of the water gate into Embankment Gardens you will see a large area with deckchairs, free to sit in, arranged facing a large open-air stage. You might even get to see a concert there in the summer. If you walk out on to the Embankment itself there’s a wonderful view of the river. Further down is Cleopatra’s Needle. This, however, has nothing to do with Cleopatra as it predates her by a thousand years. If it looks familiar it’s because it’s one of a pair – the other is in Central Park, New York. The sphinxes, by the way, are the wrong way round; they look at the obelisk, whereas they should be looking out, guarding it.

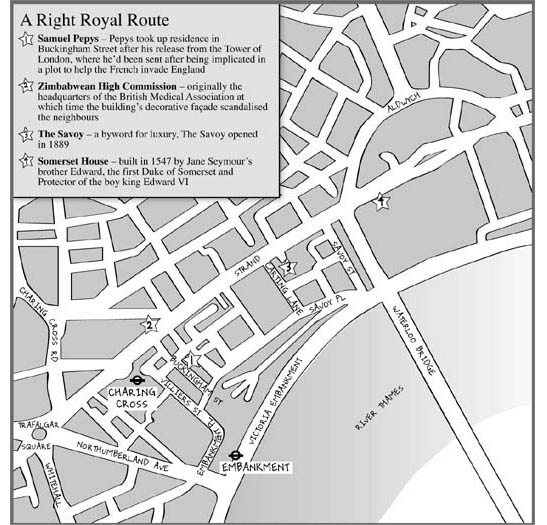

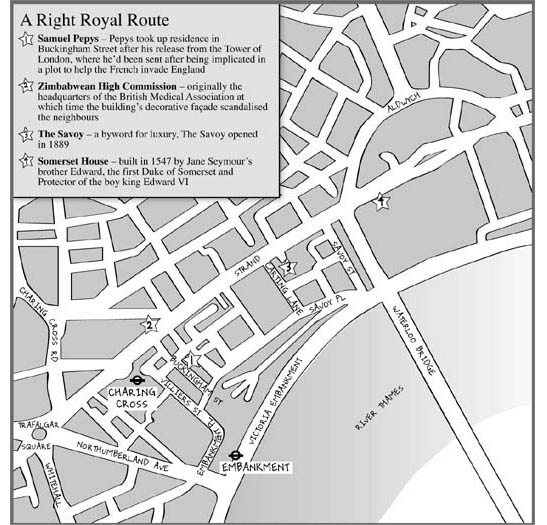

Back up at the water gate, if you walk over the archway and up the steps, this will take you in to Buckingham Street. Here you will find a plaque to Samuel Pepys, the diarist of the 1660s. If you were going to write a diary this was a good time to be doing it. The year 1660 was the restoration of the monarchy. Pepys himself, only a young man, went out on a ship to the Low Countries to bring Charles II back to be restored to the throne. Later, in 1665, Pepys’s diary records red crosses on the doors of houses in nearby Drury Lane and the words ‘Lord have mercy on their souls’. Pepys survived the Great Plague and the next year, 1666, the Great Fire. He describes digging a hole with Sir William Penn (whose son was to found a state in the US) and burying his Parmesan cheese in it, then digging it up again when the fire was over.

Pepys was not living in the house that bears the plaque when writing the diary; he came here after he’d been imprisoned in the Tower of London. For a wonderful account of the life of Pepys, read Claire Tomalin’s The Unequalled Self.

Opposite the plaque to Pepys is a house with the original fanlight window above the door and link snuffers. Until Sir Rowland Hill invented the penny post in 1840, houses did not have numbers. Instead, on letter-headed notepaper or on an invitation to visit would be the name of the street and a copy of the pattern on the fanlight window above your front door.

The link snuffers, the upturned cones attached to the railings, were to snuff out a ‘cressit’ or ‘link’, a naked-flame torch made from hemp rope dipped in pitch. It was so dark along London’s streets in the days before street lighting that those travelling by carriage would frequently pay someone to light them through the streets, the person running in front of the carriage holding a rope torch aloft. John Gay (best known for The Beggar’s Opera) wrote in his work Trivia that:

Though thou art tempted by the Linkman’s call

Yet follow him not along the lonely wall

In the mid way he’ll quench the flaming brand

And share the booty with the pilfering band.

A warning of those linkmen who had mates hiding down a dark alley and who might lead your carriage driver down there, drop his ‘link’, and in the dark he and his friends then leap out and rob the people in your coach. Those who did manage to get home in one piece would extinguish their rope links in the up-turned link snuffers.

Buckingham Street still has some lovely eighteenth-century houses in it, now all business premises. Further up you’ll find a house with masks, some like gargoyles with a fearsome aspect, protecting the occupants from evil spirits. Charles Dickens as a twelve-year-old worked here in Warren’s blacking factory while his father and the rest of the family were in the Marshalsea debtors’ prison. He came back to live in this street as a young man and used the area, before it was embanked and reclaimed from the river, as Murdstone and Grinby in David Copperfield, drawing directly from his own time working in the factory.

Further along the Strand is the Zimbabwean High Commission, built in 1907 as the HQ of the British Medical Association. Jacob Epstein was commissioned to decorate the facade and he did so with full-length representations of the human body, some clothed, some not. The nude statues caused an outcry; 1907 was, after all, the year in which the tango was banned for being too sensual. The company that owned the building on the other side of the Strand fitted opaque frosted windows so their employees could not see the scandalous naked figures. The BMA themselves eventually got a man with a hammer and chisel to remove the heads of the sculptures in the hope that this would make them seem less naturalistic. This was an act of terrible cultural vandalism, as Epstein was one of the greatest sculptors of the twentieth century. Time, the weather and the frost played its part, and other bits gradually dropped off as well, rendering them less of an offence to public decency.

The building that installed the frosted windows was in Durham House Street, the name ‘Durham House’ all that remains of the mansion that had been there since medieval times. Simon de Montford lived there, the baron who convened the first parliament without the permission of the King and then convened representatives of the burgesses of the shires to sit as commoners. When later Henry III was proceeding down the Strand and there was a terrible storm, de Montford came out of Durham House and offered him shelter. The King replied that ‘thunder and lightning fear I much, but by the head of God I fear thee more’. He kept going and got wet.

It was during the reign of Henry III that the next palace was built. Henry gave the land here – east along the Strand from Durham House Street – to his wife Eleanor of Provence’s Uncle Peter, the Count of Savoy. Today the hotel on the site – the Savoy – is one of the most famous hotels in the world. Look carefully at this road. It is different from any other road in the British Isles because drivers must drive on the right-hand side.

In the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, Londoners destroyed the Savoy Palace because the hated Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt, lived there. Disdaining to steal from the burning palace, the rioters threw a box that was thought to contain jewels on to the fire. It contained gunpowder and destroyed the great hall.

Up close – the Strand

If you go down a tiny, steep alley just past the Savoy Hotel, you will find all that is left of the old Savoy Palace, the Queen’s Chapel. Geoffrey Chaucer was married here and in the eighteenth century John Wilkinson conducted illegal weddings advertising ‘five private ways by land to this chapel and two by water’, presumably so you could get away quickly if anyone turned up to put a stop to the nuptials.

Next to the Savoy is the Coal Hole, a great pub where Edmund Kean the actor formed the Wolf Club for repressed husbands whose wives wouldn’t let them sing in the bath. Richard D’Oyly Carte built a theatre here, also called the Savoy, for Gilbert and Sullivan. It was rebuilt in the late 1920s and is a lovely example of Art Deco.

The Savoy Hotel had the first suites of rooms in England and the first electric ascending rooms. The dance floor rises as well. It’s a great place to have tea, but a riverside suite will cost you several hundred pounds a night. Auguste Escoffier was chef here and he invented peach melba in honour of Dame Nelly Melba, the Australian soprano who stayed regularly. I used to see Richard Harris there a lot, particularly in the Coal Hole, where he always appeared to be talking, not to friends, but to people he’d just met. He had a permanent suite in the hotel. Nice, if you don’t like washing up or housework.

Further east along the Strand is Aldwych with one of my favourite parish churches in London, St Mary-le-Strand. Pop your nose in. The interior is like a jewel box, a riot of Italianate baroque.

One palace that does remain is Somerset House on the Strand. Somerset House was rebuilt in the eighteenth century as offices for civil servants in impressive Portland stone. This elegant baroque courtyard looks more like a palace than nearly anything else in London. The original renaissance palace that stood there was built for Edward Seymour who was made executor of Henry VIII’s will. The new King, Edward VI, was only nine, so a council of regency was formed to help the little guy out. Edward Seymour was his uncle (the new king was Jane Seymour’s son, the only male heir to Henry). Now in a powerful position, he had himself made the Duke of Somerset and set about building himself a great palace befitting his new status. However, he did not enjoy his dukedom or his palace, because he got his head chopped off a few years later. But the name stuck and this is Somerset House, home to three fantastic art collections, the best of which is the Courtauld.

It was George III who ordered these buildings constructed. Look for the statue of him here. It’s hilarious. It looks nothing like him, the sculptor was so eager to flatter that George’s wife Queen Charlotte had no idea who it was. There are now fifty-five fountains here, which dance on the hour and half-hour and are lit up at night. There are tables and chairs strewn around which don’t belong to any café and a few clever people have realised you can take a picnic and a bottle of wine and just sit. If you have children on a warm day they will just run in and out of the fountains for hours, quite safely as there is no traffic and it’s very difficult for them to escape out of sight. If it is winter there may be an ice-skating rink.

Walk through the magnificent courtyard towards the river and out on to the balcony. There are tables set out in an outdoor café that no one seems to find where you will get a fantastic view over the river. This huge balcony leads on to Waterloo Bridge. You could walk over and see if there’s anything on at the National Theatre (where there’s often free music in the foyer), the National Film Theatre (literally under the bridge and with a great happening bar), the IMAX cinema (on top of the bridge) or the Royal Festival Hall. Music, drama and film, then, for an evening’s entertainment after your walk.