SUE JACKSON

On Christmas Day 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey, and the Middle Ages began. Or at least this is as good a starting point as any. William would largely control his new kingdom by force but, faced with the ‘restlessness of its large and fierce population’, he was wise to approach the citizens cautiously.

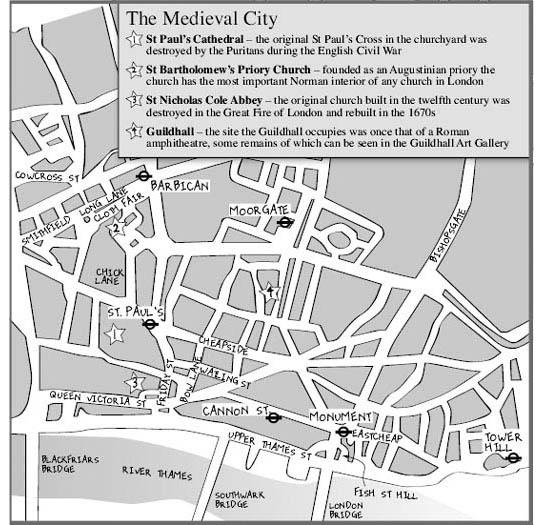

IN A GESTURE of conciliation, William confirmed all their existing rights and privileges in a document known as William’s Writ. For his part, he inherited a city that was already well organised, and to a degree self-governing, a city that was wealthy, proud and conscious of its power. By the early Middle Ages, the boundaries of the city had expanded beyond the old walls to encompass an area of about a square mile, the Square Mile that is virtually unchanged to this day. The great Old St Paul’s Cathedral dominated Ludgate Hill and throughout the area a forest of spires rose above the skyline. Beyond the walls to the north was the ‘smooth field’ – corrupted to ‘Smithfield’ – an open space used for entertainment, sport, executions and where a weekly horse fair and meat market was held.

Outside the wall to the west flowed the River Fleet, a natural defence and the means by which goods could be brought deep into the city. At the end of the eleventh century, a prison was built on its banks. On the south side of the city, the remains of the old riverside wall were at this time crumbling into the Thames, to be replaced by stone warehouses. London was now a thriving international port and the river, the main highway of London, ‘teeming with craft’.

By 1209, a stone London Bridge over the Thames had been completed that was to last more than six centuries. At its centre was a chapel dedicated to St Thomas Becket, a Londoner who had risen to become Archbishop of Canterbury. The bridge was crowded with houses and shops. Its gatehouse displayed the gruesome sight of severed traitors’ heads.

Huddled together along the narrow streets and alleys of the city were overhanging thatched houses and shops. Down the centre of the stinking and filthy lanes ran gutters, overrun with rats, into which everything, including human slops, was thrown. Cats, dogs, hogs and chickens wandered freely. Rubbish piled up and some streets served as open sewers, most obviously Cloak Street, which was originally Cloaca (sewage) Street.

WHERE TO READ THIS

You might sit and read this story in the old churchyard of St Bartholomew’s Church, Smithfield. Here you will be sitting in what was once the covered nave of St Bartholomew’s priory church of 1123, later the graveyard – which is why you are four feet above the level of the remaining south aisle! The lower part of the gatehouse dates from the late thirteenth century and one side of the cloisters still remains.

William balanced the benevolence of his Charter by building formidable strongholds. The wooden stockade he had built on the east side of the city would, by the end of the eleventh century, be replaced by the great stone keep later known as the White Tower, with walls up to fifteen feet thick. Commanding the eastern approach to the city, it served as a threatening presence not only to possible invaders but to the Londoners themselves, and it was echoed on the western side by Baynard’s Castle and Montfichet Tower.

Little remains physically of the medieval city, except the Tower, parts of the walls, the odd crypt and sections of churches, but it is still possible to conjure up a vivid picture of what it must have been like from the street names which haven’t changed, the multiplicity of blue plaques recording the location of many ’lost’ churches and livery company halls.

The Normans were nothing if not organised and efficient. All over the city, churches were built or rebuilt. By the end of the twelfth century, there were an estimated 126 parish churches, one on virtually every corner. Many were dedicated to the same saint – there were sixteen St Mary’s for example – often with a distinguishing suffix. Sometimes this was the name of the church’s benefactor, for example, St Martin Orgar or St Lawrence Pountney. St Margaret Patten refers to the raised iron shoes or pattens made in the adjacent lane to protect clothes from the mud, and St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside is named after the arched vaulting in the crypt. And it was the great tenor bell of that church that signalled the nine o’clock evening curfew when all citizens had to be back within the walls. True citizens of the city were those who lived within the sound of Bow Bells.

The churches, part and parcel of everyone’s life, were tiny and dark, lit by candle and perfumed with incense. The walls were painted with biblical stories – most people were illiterate. The mass was murmured through the sanctuary screen, confessions were made (though probably only once a year, in Lent), marriages performed in the porch, and the dead buried in the churchyard, which over the centuries rose to several feet above ground level. The seatless naves of churches were often used as public meeting places or, as time went on, for commerce.

Sermons would be attended elsewhere – and the citizens loved a good sermon, particularly at St Paul’s Cross in the cathedral’s churchyard. A wooden pulpit surmounted by a cross, it also served as a place where proclamations were made – to announce royal deaths and births, victories or defeats – and where felons were punished. In 1087, the Saxon cathedral burned down, to be replaced by a vast stone building, the spire rising to 450 feet above the ground. The rose window on the east wall became so famous it was replicated in embroidery, as on Absalom’s slippers in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

In the churchyard was the Jesus Bell Tower, which summoned the citizens to the great assembly or folkmoot on Christmas Day, Midsummer’s Day and Michaelmas Day. Booksellers, usually itinerant, set up their stalls permanently here, and became known as ‘stationers’ as they were no longer on the move.

From the thirteenth century, monasteries, priories and abbeys found space on the edges of the city – Augustinians, Franciscans, Carmelites, Benedictines, Carthusians, Dominicans and others – all came to preach to and help the poor. Chaucer, living above Aldgate as a collector of dues on goods entering the city from the east, was able to observe them, and have them find a way into his Canterbury Tales. Of the nine religious characters on pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral, virtually all of them are corrupt. Right under Chaucer’s nose in Aldgate was the vast Holy Trinity Priory (some of the remains of which are preserved in an office building in Mitre Street). Founded by Queen Matilda in 1108, the priory spent so lavishly on fixtures and fittings that the brothers hadn’t enough money for food. Further, its prior forced the brothers to swear that a Mrs Joan Hodgiss was the official embroideress, rather than his mistress. When Henry VIII closed the priory down in 1532, no one was sorry to see them go.

It wasn’t unusual for unmarried women to enter a nunnery, where life might be pretty comfortable. St Helen the Great’s Priory became notorious for its frivolity, the nuns having to be ticked off for rushing through their services, wearing ostentatious veils and kissing secular persons. The prioress was ordered to keep to her own room.

Up close – Life in Medieval London

Still surviving on Smithfield are the remains of St Bartholomew’s Priory Church. Built in 1123, and with vast Norman columns and arches, it is the oldest parish church in the City. Although the nave has been pulled down, two stumps of pillars that supported the south aisle roof remain.

So the Church was part of the daily fabric of life in the Middle Ages and its teachings and strictures influenced almost every aspect of life. Diet, for example. At certain times during the year meat was forbidden by religious observation and fish was substituted instead – its importance evident in street names such as Fish Street Hill, near Billingsgate, where most fish was landed, Old Fish Street and Friday Street, near St Paul’s, where fish was also sold. The local church was St Nicholas Cole Abbey in Queen Victoria Street, St Nicholas being the patron saint of sailors and fishmongers. Many of them are buried here.

But meat was the staple, and Smithfield was the meat market. Beasts and poultry were brought to market along the nearby lanes, which gained predictable names such as Chick Lane and Cowcross Street. Sold and slaughtered, the offal from the animals was thrown into the River Fleet. Smithfield apart, the main market streets were Cheapside and Eastcheap – ‘cheap’ from the Anglo-Saxon for ‘market’. The names of their side streets tell us where the various traders had their houses and shops, each gathered together in one area, for example Bread Street, Milk Street, Honey Lane, Ironmonger Lane, Poultry.

To practise a trade meant joining the relevant guild that protected and promoted that trade. A young boy of about fourteen years would serve a seven-year apprenticeship and it was the Master’s responsibility to house, clothe and feed him. If his work ‘passed Master’ he could set up on his own and gain the freedom of the City. And being a Freeman was the passport to possible position and fortune. But apprentices had a reputation for getting involved in fights at the drop of a hat, drinking too much and being only too easily distracted by the lure of sport and entertainment. Chaucer sums it up in ‘The Cook’s Tale’:

There was a prentice living in our town,

Worked in the victualing trade and he was brown.

At every wedding would he sing and hop

And he preferred the tavern to the shop

Whenever any pageant, goodbye to his profession

He’d leap out of the shop to see the sight

And join the dance and not come back that night.

And, indeed, in the first written description of London of 1177 by William FitzStephen, though waxing lyrical about virtually every aspect of the city, he condemns the ‘immoderate drinking of fools’.

By the Middle Ages, there were over one hundred guilds. By the late fifteenth century, in an attempt to settle the many disputes that had arisen over precedence, the companies were put in order and the top twelve were, and are, known as the Great Twelve. Unsurprisingly, it was the merchant element that held sway over the craft guilds. Number one were the Mercers, controlling the fine cloth trade – but the Fishmongers and the Salters were there too, salt being so important in preserving meat and fish. Numbers six and seven were the Skinners (furs) and the Merchant Tailors. So persistent were the latter in arguing that they should be number six, that in the end the Skinners and Tailors were ordered to swap places each year, a custom that, it is said, gave rise to the expression ‘to be at sixes and sevens’.

Every August, in the precincts of St Bartholomew’s, a cloth fair was held, with merchants coming from all over Europe. Temporary courts were set up to deal with any complaint that arose and these were known as ‘courts of pie powder’, a corruption of ‘pieds poudrés’ – or dusty foot, the notion of justice on the hoof along the dusty roads before the fair moved on. Here, a local tavern called the Hand and Shears was used as a court and its successor still stands today on Cloth Fair.

Most of these livery companies and their rebuilt halls still exist, though many are no longer actively involved in the original trade. Exceptions are the Fishmongers, whose Fishmonger’s Hall still stands alongside London Bridge and whose members still examine the quality of fish at Billingsgate market. The market is now located in Docklands, where the rent is one fish a year. Meanwhile the Goldsmiths still weigh new coinage in the Assay Office at the Trial of the Pyx and are still involved in the jewellery trade. Down near the river was and is Vintners Hall in Upper Thames Street, where the wine merchants dealt, and the name of the nearby church, St Michael Paternoster Royal, College Hill, is a reminder of La Reole, a district of Bordeaux where the wine came from.

There was time for recreation in daily life. There was always the chance of a game of football on Smithfield, miracle plays to watch, dog fights, archery and ice-skating on the frozen watery meadows of Moorfields in winter, where skates could be fashioned from animal bones. The youth were nothing if not reckless and games were often dangerous, if not fatal. Best of all, there might be an execution – perhaps a beheading on Tower Hill or a hanging, drawing and quartering on Smithfield. Citizens were expected to attend executions, which were intended as a deterrent. You got a day off and plenty to drink and eat and you could cheer it all on. In 1305, William Wallace suffered a horrific traitor’s death at Smithfield, his head later ground on to a spike and placed on the gatehouse of London Bridge as a terrible warning. The Tower itself was of course an object of fear associated with dark tales of imprisonments (often of the high and mighty), torture and escapes. The Bishop of Durham famously swung to freedom from the top of the White Tower on a rope which had been hidden at the bottom of a barrel of wine he’d spirited into his cell.

And the Tower continued to grow, to include two concentric walls and further towers circling the central keep. A menagerie was set up during Henry I’s reign and he received as a gift three leopards and lions, alluding to the royal coat of arms, a polar bear and even an elephant, which no one had ever seen before.

As the Middle Ages progressed, wealthy individuals built fine houses all over the City. These were usually merchants or aldermen who made most of the vital decisions regarding the affairs of the City. Power resided with them, and the City gradually but inexorably consolidated its independence. In 1215, King John confirmed its right to elect a Mayor on condition that an oath of allegiance be sworn to the monarch at Westminster. Thus was born the Lord Mayor’s Show, which continues to this day. Then, as now, within the City the Lord Mayor took precedence over everyone except the monarch.

The Mayor, who would already have held the post of sheriff, came to be elected from the Court of Aldermen. But the platform on which the City’s government rested was the Court of Common Council, which developed from the folkmoot, and provided some six to eight representatives from each ward. Meetings were held in the Guildhall, on the corner of Gresham Street and Aldermanbury, which was always the centre of civic government and certainly existed in the twelfth century. Parts of today’s building date from the early 1400s.

If little physically remains today of the City of the Middle Ages, it does still rest on a network of medieval streets and their evocative names. Many of the churches are of medieval origin, and the livery companies still exist and play an important role within the City, their medieval traditions and ceremonies still played out. The government is still made up of Lord Mayor, sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen, and Midsummer’s Day and Michaelmas Day are still the dates on which the sheriffs and Lord Mayor are elected.

The City is still fundamentally medieval and is still the ‘flower of cities all’.