FLEET STREET – ‘SMALL EARTHQUAKE IN CHILE: NOT MANY DEAD’1

ADAM SCOTT

Of all the Londons hidden along storied Fleet Street – the London of the pre-Reformation bishops, of the long-dissolved monasteries, Londons of half-forgotten battles, fire and riots, of mythical close shaves and cannibalism – the London most recently departed is the hardest to find. Our business – raking up the past – takes on a new twist here. In this neck of the woods, the past has long been a valuable commodity. Especially a sordid past. A scandalous past. An incriminating, shameful past. The kind of back story that shifts newspapers.

THE PAST BELONGING to the newspapers themselves, however, is another matter. Perhaps Fleet Street hides its recent history because the biter seldom likes to be bitten. Maybe it’s too early to be tossing plaques and platitudes around – it is, after all, only twenty and some years since the printing business’s exodus from its home of five hundred years. The business of news exists entirely in the present. Who indeed, as Mick Jagger (himself a scarred veteran rider of the newspaper tiger) once asked, wants yesterday’s papers? The answer to that is easy: we do. Unearthing the past is rewarding work, setting history in hot metal as opposed to pushing computerised pages across a silent screen.

WHERE TO READ THIS

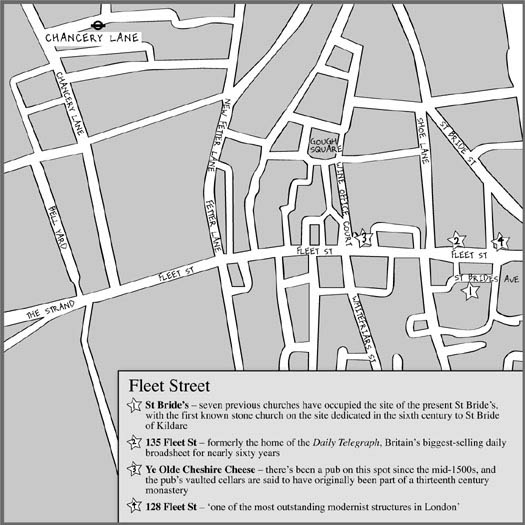

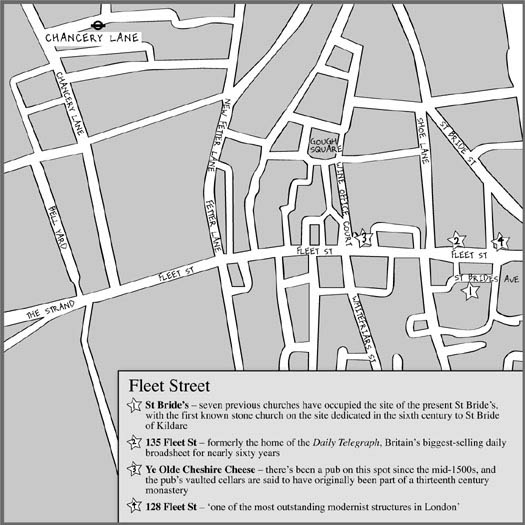

London teems with enclaves that, just a few steps off the roaring highway, afford a peace and quiet greatly at odds with their noisy surroundings. These insider’s hideaways spring up where one least expects them – and they come no better than at St Bride’s churchyard.

All along Fleet Street

Like all wide-eyed, fledgling newspapermen we will start at the top, only to find ourselves sinking inexorably to the bottom. The devil has all the best tunes, they say: and all the circulation-boosting stories, too. The top in this case is the western extremity, where we get precious little help from a famous man of letters. Who, after all, would collude in the exhumation of ghosts that want to be left well alone? Certainly not Samuel Johnson, loitering behind St Clement Danes where The Strand meets Fleet Street.

In a statue by Percy Fitzgerald, the good doctor seems intent on minding his own business: knees bent in a sprightly walk, nose buried in a book, a ‘Who sir? Me sir?’ attitude surrounds him like the smoke of a surreptitious fag in the school toilet. He’s even standing in The Strand, just shy of Fleet Street itself, trying to disguise a sidelong glance down that fabled thoroughfare. He couldn’t look more guilty if he were self-consciously whistling a jaunty air. Cast as both gatekeeper and denouncer, this St Peter of Fleet Street seems set to surpass the fiery apostle’s hat trick of denials and then some. ‘Fleet Street? Me? A man of my standing?’

Don’t you believe a word of it. Try as he might, Johnson will later give himself up. We know, as the old saying goes, where he lives. Better yet in Fleet Street: we know where he lunches.

Reuters has gone, the last of the big boys to leave, departing its Edwin Lutyens-designed building in 2005. D C Thomson is the last man standing, its London HQ guarding the western extremity of the Street. Unsuccessfully, as it turns out. The Scottish megalith publishes both the Beano and the Sunday Post (once the world’s biggest sale, achieving the unique feat of having readership figures in excess of 9 million). The names of its stable – People’s Friend, Dundee Evening Telegraph – are set into the very fabric of the building. In anticipation of a thousand-year Reich? Newspapermen should have known better.

Journalists come and go. Newspapers, likewise. The blank look in the eye of your news vendor when you ask for a copy of Today (dead since 1995) the Sketch (1971), the Chronicle (departed 1930, coincidentally in the same year as its most famous correspondent, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) or even the Post (launched and folded within five weeks in 1985) is testimony to that. We’ll not be sentimental, though: the Street would never have allowed it. That the nickname of the famous journo watering hole the White Hart was ‘The Stab in the Back’ suggests that sentimentality was never welcome here at the best of times.

That ‘The Stab’, like the papers and the presses, is also long gone brings us to a change in the Street, less well documented than the moving of Murdoch and his News International stable to Wapping in the mid-1980s.

The King and Keys, the old Daily Telegraph pub, closed recently without so much as a squeak. Forty years ago, the headline ‘Pub Closes In Fleet Street – Drinkers Go Elsewhere’ would have been a ‘Man Bites Dog’ sensation. In polite tourism circles the Street is known as ‘The Street of Ink’. By those in the know, this has long been seen as a misprint, an error on the subs’ desk. Of course, ink has been integral to the neighbourhood since the 1400s, but there has been another fluid just as vital to the folklore of the place. It’s not ink. But it sounds like ink.

Sitting proud of Fleet Street over in the People’s Republic of Soho, that enclave of non-conformity providing the perfect base from which to throw brickbats, the satirical magazine Private Eye still has fun with the antics of newspapermen and women, in its fictionalised old-timer Lunchtime O’Booze. Indeed, that magazine coined the popular euphemism for inebriation, ‘tired and emotional’, tailored for George Brown, the Labour politician of the 1960s whose thirst made even those on Fleet Street seem tame by comparison.

Up close – Fleet Street

The great editor of the Daily Express Arthur Christiansen (in the chair from 1932–56) always reminded his staff: ‘Never forget the man in the backstreets of Wigan’ – never, in short, lose touch with the Common Man. The common man in London terms was always ‘The Man on the Clapham Omnibus’, a description created by Fleet Street’s bothersome, killjoy neighbours, the legal profession in the early twentieth century as a metaphor for the ordinary man in the street. The title was resurrected by the late Stewart Steven when editor of the Evening Standard as a byline for one of that paper’s columns in the early 1990s. As for the omnibus itself, there are still a couple in service. The No. 15 Routemaster is one of only two ‘heritage routes’ (the other is the No. 9) that still trundle and growl their way through central London. Pick up the No. 15 at Trafalgar Square and it will take you clear to Tower Hill – via Fleet Street, of course. Aggressive in acceleration and growling noisily – a bus that behaves like a born Londoner – the Routemaster was only in production between 1954 and 1968 but was a good and faithful servant to the metropolis for a further thirty-seven years.

Despite recent closures, the Street still retains a retinue of fine pubs and bars – including the first Irish pub outside the Emerald Isle. A refreshing change from the chain homogeneity of those dismal Feck O’Donnell’s Green Beer Emporia, the Tipperary at 66 Fleet Street was formerly the Boar’s Head (from around 1700) and was renamed by the print workers returning to the Street after the end of the First World War (after the popular song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’). Built on the site of a monastery where the monks brewed ale, it was the first pub in London to sell both bottled and then later draught Guinness.

The Irish connection holds true at the bottom of the Street, too, in the shape of the journalists’ church, St Bride’s on St Bride’s Avenue. St Bride is not, paradoxically, the patron saint of journalists – that difficult job belongs to St Francis de Sales. Neither does she particularly watch out for women on their wedding day – although Wren’s tiered spire for her church was the inspiration for the traditional wedding cake. St Bride occupies an honoured place in the pantheon of Irish saints bettered only by St Patrick himself. Her miracle? She turned the water into … beer.

A walk along Fleet Street becomes a mere frivolous skip down memory lane if we do not acknowledge the mighty Irish contribution to English letters. It is best summed up in the words of a West End man who spent much of his professional life on Fleet Street: Kenneth Tynan, legendary drama critic of the Observer (the world’s first Sunday newspaper, established in 1791). Of the great dramatist (and fierce drinker) Brendan Behan, he put it thus: ‘The English hoard words like misers: the Irish spend them like sailors on leave.’ How much poorer would our Fleet Street and literary culture be if they hadn’t? Without T P O’Connor’s title the Star (founded 1887), for example, we would lack some of the most vivid reporting on the Jack the Ripper case.

Words remain the currency here; even now the papers have gone. We may live in the digital age but, as sure as Dogs’ Home follows Battersea, Fleet Street is still wedded to journalism, even now that the lawyers have gleefully spilled in like so many cuckoos from their neighbouring enclave.

It is both an irony and a frustration that the Street always had the Law peeking over its shoulder, twirling the baton of libel like some overzealous policeman looking for trouble. With rich and scandalous pickings at either end of the Street, our old-school editors must have drooled all morning long. No wonder they needed a drink come lunchtime.

And what temptation: at the eastern extremity lies the City. And to turn that old northern capitalist’s cliché upside down, where there’s brass, there’s muck. At the other end there’s the City of Westminster, where the good people of London go to enjoy themselves. And where, on occasion, having enjoyed themselves a little too much, they turn from Jekylls into Hydes. Perfect fodder for the front page. Our politicians also work there. But surely that unimpeachable bunch wouldn’t ever trouble our newspaper editors with their above-board endeavours and pastoral leisure pursuits. Would they?

Rather like the proverbial bad surgeon, Fleet Street buries its mistakes. Or rather, it spikes them, an act that also functions as a rather delicious allusion to London’s gruesome past. And those who have published that which should have been spiked have been, if not quite damned, then certainly slapped on the wrist for libel. Sometimes slapped in irons.

The first Fleet Street libel case involved the publisher and editor John Walter. Walter founded the Daily Universal Register on New Year’s Day 1785. As a third birthday present for his publication, he gave it a new name, the name by which it has been known these last 220 years: The Times. Eighteen months after that he was sentenced to a year in Newgate Prison for a libel on the Duke of York.

His publication gained the satirical epithet ‘The Thunderer’ in the 1840s. But the only building that thunders on Fleet Street – even today – is the former HQ of rival publication the Daily Telegraph. Elcock and Sutcliffe’s Egyptian-inspired edifice at No. 135 was home to Britain’s biggest-selling daily broadsheet from 1928 until 1987 when it followed the exodus east, ending up at 1 Canada Square at the horribly nicknamed ‘Vertical Fleet Street’ (it’s since flitted back west to Victoria). Amid the timid Victoriana of the Street, this impressive ‘newspaper palace’ looks as if it has dropped directly from Batman’s Gotham City. And if you look up high, just below the level of the old director’s penthouse apartment, you can still see shadows of things that have gone before: the 3-D lettering is long gone, but the words ‘Daily Telegraph’ are still spelled out in sooty relief, looking for all the world like inky finger smears. London’s dirt still makes the names of the newspapers here.

The Telegraph, that bastion of the establishment, has long enjoyed a reputation, amid all its austerity, for being a paper that rather enjoys writing about sex. So much so that many consider it to be the home of the Marmalade Dropper: a story so salacious, so downright filthy, a threat to the established order and, therefore, so riveting, that one’s attention is taken utterly. The newspaper reader, sitting happily at breakfast, is suddenly gripped by a headline. With toast poised precariously halfway between plate and ever-gaping mouth, the tale consumes his interest. Reading on enraptured, he forgets the toast altogether – until, that is, the marmalade plops into the lap of his cavalry twills.

It is not, however, the proximity of scandal and skulduggery that brought the Press to this part of town. That distinction falls to Wynkyn de Worde, assistant to Joseph Caxton, father of the printing press. When de Worde inherited the business from Caxton in 1491, he simply moved it to where his customers were. In this case, just outside the City wall, to be near the educated and literate brothers at the Blackfriars monastery.

The church still enjoys a strong presence in this street so often concerned with lower matters. St Bride’s has St Dunstan-in-the-West (186 Fleet Street) for company (its namesake in the east a bombed-out shell converted into the City’s prettiest garden). Its location, on the north side of the Street, has accommodated a church for some thousand years. The current St Dunstan’s is the work of John Shaw the Elder, completed by his son John the Younger and opened in 1883. It is dedicated to a popular British saint and former Archbishop of Canterbury who, legend has it, caught the devil by the nose and hammered horseshoes into his hooves. I wonder how he would have been immortalised by the subs desk of the Sun? Perhaps: ‘Hoof Sorry Now?’ ‘Dunstan Casts Devil to the Land of Shod’? Or ‘Dunstan and Dusted!’? Come to think of it, ‘Gotcha!’ would work equally well.

What Samuel Johnson would have made of the inclusion of the word ‘gotcha’ in his dictionary we can only speculate. Perhaps he would have tried to distance himself from such vulgarity. Had Johnson’s home at nearby Gough Square not been turned into a wonderful museum, or if we couldn’t find his cat Hodge (in statue form) waiting for his master, we would still have evidence to catch the Doc red-handed as a pillar of this inky community. For his spirit is still in Fleet Street – in liquid form at the bar at one of Johnson’s favourite haunts: Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese (145 Fleet Street in Wine Office Court).

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese has a board outside that reads like a who’s who of Eng. Lit. Johnson tops the bill, alongside a roster of some fifteen monarchs who have reigned over us, happy (and miserable) and glorious (and ignominious). And one can ask for Johnson’s spirit by name: it is brandy. ‘Claret,’ he said, ‘is the liquor for boys; port for men; but he who aspires to be a hero must drink brandy.’

The most salacious item ever served on the menu at this historic pub was a very cold dish indeed: Dead Man’s Letters. During the days of the death penalty (abolished finally in 1971), informants keen to make a few bob from the insatiable papers could strike up correspondence with condemned men. Doomed to dance at the end of a rope, the miscreant would often be found on fine confessional form. The correspondence would turn into a friendship and the memories and confessions would pour forth like water. On the day of the hanging, the dead man’s new best friend would hot-foot it to the Cheshire Cheese where he would sell the story to the highest bidder. These latter-day Resurrection Men profited not from the contents of dead bodies, but the more ephemeral cargo of departed memories.

Nearing the bottom of the Street, the elegant No. 128 glints into view – arguably the Street’s most famous building. Just as the Telegraph was still preening in all its Citizen Kane-ish glory, along came Ludgate House a mere four years later. It remains one of the most outstanding modernist structures in London. Perhaps it is even a mark of our reticence to embrace the architectural new that it still stands out as outré some eighty years after its creation. Nicknamed the Black Lubyanka (again by Private Eye, a nod to the Moscow HQ of the KGB) it boasts London’s first ever curtain wall. Behind this architectural first, the beautiful Art-Deco foyer captures Express proprietor Lord Beaverbrook’s vision of his beloved British Empire. One wall is a fresco of scenes and riches from the former colonies, the other of the might and splendour of England. Linking the two across the tiled floor, a series of wavy lines, undulating from wall to wall representing those waves ruled, of course, by Britannia.

One Fleet Street legend from the newspaper days remains unexplored – El Vino’s. And it’s still there, back up the hill at No. 47.

The closest this bunch of rogues and footpads ever had to a gentlemen’s club (once upon a time, not so very long ago, women were forbidden from ordering at the bar), El Vino’s was a great favourite haunt of my late father-in-law, Commonwealth Press Union supremo Terence Pierce-Goulding, who loved its unassuming atmosphere cloaked in coat-and-tie formality. Robert Edwards, editor of four national papers including the Express at the height of its powers (when it sold 4 million copies a day in the 1960s) records it wistfully in his autobiography, Goodbye Fleet Street. The distance between the Express and El Vino, he bemoans, was just too great to cover if Beaverbrook called on the phone. From many another hostelry, one could be back at one’s desk in a matter of mere minutes, pretending to have been in a meeting with the chapel (as the printers’ unions were known). Not so El Vino’s, making it out-of-bounds for Edwards of a lunchtime. A good thing, if you ask me: the ample charms of this great Fleet Street institution are too great to be interrupted by anything – even a call from Lord Beaverbrook.

Now that the Fleet Street era of newspapers is over, it is perhaps appropriate that we end our tale with that most forbidden of old Fleet Street lunchtime fluids: water. The Street, after all, takes its name from the shadowy Fleet River that rises on Hampstead Heath and runs beneath its eastern extremity before making its final watery genuflection at the hem of the Thames beneath Blackfriars Bridge. Traces of the old newspapers are almost as hard to find, twenty years after they went east, as the elusive Fleet River itself. But while the Street these days chains together the two great beasts of City and Westminster, its very name remains soaked in ink. No Londoner in the twenty-first century thinks cabbages and carnations at the mention of Covent Garden. But the words Fleet Street still set the presses thundering and the headlines spinning in the Moviola of the popular imagination.

1. Winner of unofficial, in-house Most Boring Headline Competition at The Times, early 1950s