CHARLES DICKENS’S A CHRISTMAS CAROL

JEAN HAYNES

This is a walk for the wintertime. ‘It is required of every man,’ quoth the ghost of Jacob Marley, ‘that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow men … and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death, to wander through the world and witness what it cannot share but might have shared and turned to happiness.’

LET US GO forth and wander, as Dickens often did, the streets in search of A Christmas Carol and the transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge, ‘hard and sharp as flint and solitary as an oyster’. Dickens’s story was written with the purpose to act as a ‘sledge hammer’ to rouse the public spirit on behalf of the poor and destitute. It has never been out of print! The Christmas book, and it moves us still.

The ghosts of London past

Intertwining the story are the festive decorations, the myths and customs which celebrate the season as we walk the City streets. Scrooge knew his city well. His counting house was here and his dwelling nearby. It’s a gloomy house and the very large knocker on the front door is described in the story as taking on the appearance of Scrooge’s dead partner – who died ‘seven years ago, this very Christmas Eve’– with ‘a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar’. (There’s a similar door-knocker on the Hung, Drawn & Quartered pub in Great Tower Street.) St Dunstan’s Hill may have been the location for Scrooge’s house, as Dickens makes reference to the saint who, with his red-hot tongs, tweaked the Devil’s nose: ‘Foggier yet and colder … if the Good St Dunstan had nipped the evil spirit’s nose with a touch of such weather as that, then indeed he would have roared to lusty purpose.’

WHERE TO READ THIS

Trinity Gardens on Tower Hill has seats and is pleasant in fine weather. The walk starts there. Or try one of the pubs/eateries in Leadenhall Market, or the Crypt at St Paul’s.

Travelling westward along Eastcheap, we come to an elaborate building over the way which stands near the site of the tavern where Falstaff, Prince Hal and their crew used to carouse – the Boar’s Head. If you look up, beneath the central arch, there is a representation of the beast emerging from some rushes, which evokes an ancient yuletide song, ‘The Boar’s Head Carol’. Its origins are in a Scandinavian yule feast, in praise of a dish sacred to the heroes in Valhalla. It is celebrated still. On 16 December each year at the Cutlers’ Feast in London, St Paul’s Choir sings ‘The Boar’s Head in hand I bear, Adorned with bay and rosemary’ as the boar’s head is carried in procession, the traditional apple in its mouth.

Carols were not religious to begin with but grew out of round dances at feastings. Suppressed in the seventeenth century, these songs were revived and rightly should not be sung until Christmas Day. In London, carols were sung by the official band of ‘City Waits’ and this is the name of the tune of the carol most associated with Dickens’s tale. A boy comes to Scrooge’s door and begins ‘God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen’, but is soon chased off. The Waits were very jealous of their official standing and if an opposition choir set up, would resort to fisticuffs.

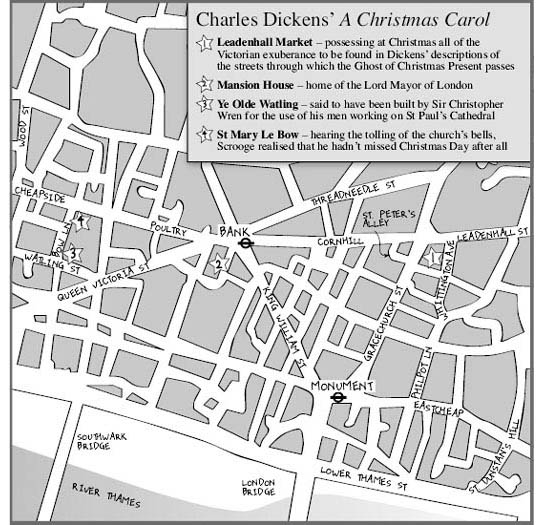

We now cross the road to Philpot Lane. An Italianate building stands at the eastern corner. If you look carefully you’ll see two little mice set on the join between this building and the next. They are a reminder of the mice that stole the builders’ bread and cheese while the shop was being erected. Forward now to Leadenhall Market. Although built after Dickens’s time, in 1881, Leadenhall has all of the Victorian exuberance he wrote about and a link with Dickens’s description of the streets through which the Ghost of Christmas Present passes:

The fruiterers were radiant in their glory. There were great round-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen lolling at the doors and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence: there were pears and apples clustered high in blooming pyramids … piles of filberts, mossy and brown … bunches of grapes … Norfolk Biffins [a kind of apple] squat and swarthy, setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons … The scales descending on the counter made such a merry sound … the canisters were rattled up and down like juggling tricks … the candied fruits so caked and spotted with molten sugar … the figs were moist and pulpy … the French plums blushed from their highly decorated boxes … everything was good to eat and in its Christmas dress … but the customers were all so hurried and eager in the hopeful promise of the day that they tumbled up against each other – clashing their wicker baskets wildly, and left their purchases upon the counter and came running back for them – in the best humour possible.

Crossing the Central Hall is Whittington Avenue, named after the famous Lord Mayor of London who is celebrated as that poor boy-cum-entrepreneur, ‘Dick’, in pantomime. The topsy-turvydom of pantomime has its roots in the old Roman Saturnalia and Whittington Avenue is as happens on the site of the Roman Forum and Basilica. At such festive times merriment and anarchy prevailed. Roles were reversed: masters served their servants. ‘Disguising’ or masking took place, which later occurred also in the old Mumming Plays of St George and the Dragon. The metamorphosis of pantomime continued in Britain as an import from Italy, the Commedia del Arte with its Harlequin and Columbine and Pantaloon. The London pantomimes date from the time of John Rich, a famous eighteenth-century Harlequin. Transformation scenes and cross-dressing remain today in our modern ‘Panto’ shows.

There is usually a large Christmas tree set up in Leadenhall, an evergreen symbol of Eternity, as is the greenery of the florists. Holly to remind us of the blood on the Crown of Thorns; ivy to keep out the witches; and mistletoe, the ‘Golden Bough’ with its white berries, a kiss for each under the Kissing Bunch. Viscum album it is named – ‘all heal’ – and is good against hypertension, but poisonous. It is the wood with which the evil Norse spirit Loki killed Balder the Beautiful, a pagan connotation and so not used in church decorations.

One special piece of greenery is the Glastonbury Thorn. Legend says the tree sprang from the staff of Joseph of Arimathea when he stuck it in the ground of Wearyall Hill in Somerset while escorting the young Jesus here (‘And did those feet in ancient time, Walk upon England’s mountains green?’). The Queen is sent slips of this tree, which is said to flower on Christmas Eve, for her table display.

Now cross Gracechurch Street and head down St Peter’s Alley, where the pub is called the Counting House. Very appropriate, as we are in the vicinity of Scrooge’s office in St Michael’s Churchyard:

The ancient tower of a church whose gruff old bell was always peeping slyly down at Scrooge out of a Gothic window, became invisible, and struck the hours and quarters in the clouds with tremulous vibrations, afterwards, as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head, up there. It was cold, bleak, biting weather … and the fog came pouring in at every chink and keyhole so that, although the court was of the narrowest, the houses opposite became mere phantoms.

When seven o’clock came that Christmas Eve, Scrooge grudgingly allowed Bob Cratchit to go home and take Christmas Day off – ‘Be here all the earlier next day!’ Grudgingly, for until 1870 bank holidays were unknown: ‘The office was closed in a twinkling and the clerk went down a slide on Cornhill at the end of a lane of boys, twenty times in honour of its being Christmas Eve.’ We, too, will go out into Cornhill, past the George and Vulture, where Mr Pickwick was ‘suspended’ prior to the breach-of-promise trial, past Simpsons, another old chop-house, both looking very much as they did in Dickens’s day and where, at the former, his descendants still meet to toast his memory.

Up close – A Christmas Carol

In St Martin-le-Grand, there is a statue, that of Sir Rowland Hill, outside what was the main Post Office. It was he who in 1840 instituted the Universal Penny Postage, encouraging communication which, a few years later, included the first Christmas card. The stamp on these letters and cards was the ‘Penny Black’ with an image of the young Queen Victoria. It was her consort, Prince Albert, who made popular that ‘pretty German Toy’ – the Christmas tree.

We have reached the Royal Exchange where, when Scrooge was being shown by the Spirit of a Christmas Yet to Come, ‘He saw no likeness of himself among the multitudes that poured in through the porch’, and his heart was full of dread that his ‘place knew him no more’. At Bank Junction is the home of the Lord Mayor of London, during his year of office: ‘The Lord Mayor in the stronghold of the mighty Mansion House gave orders to his fifty cooks and butlers to keep Christmas as a Lord Mayor’s household should.’ Leftovers from such festivities were handed out through the side windows to the poor, who lined up for such treats.

Christmas pudding for the day was traditionally made on the Sunday before Advent, ‘Stir up Sunday’. The church Collect for that day runs: ‘Stir up, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people that they, plenteously bringing forth the fruit of Thy good works, may of Thee be plenteously rewarded.’ In A Christmas Carol, Mrs Cratchit’s pudding was a source of anxiety for them all; she over its consistency; the young ones that someone might have got over the back wall and stolen it:

Hello! A great deal of steam. The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like washing day – that was the cloth; a smell like an eating house and a pastry cooks next door … Mrs Cratchit entered with the pudding like a speckled cannon ball … blazing in half of half a quartern of ignited brandy and bedight with Christmas holly stuck in the top.

The Cratchits were slightly better off than the tailor and his wife who would have dined off beef. No goose for them, though even the Cratchits’ was a small one, ‘eked out by the apple sauce and mashed potato, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family’.

People used to save up all the year round in Goose Clubs and when Christmas came their names were drawn out of a hat. If lucky, their goose was large; if not, the difference in money for a small goose was made up in ale – pleasing the men, but not their wives with mouths to feed. The fowl would be taken to the baker’s to be cooked, along with many others, in his big oven at the cost of a few pence. The young Cratchits claimed they had identified their own by the aroma as they came home. Later, after his reformation, Scrooge sent them an enormous turkey: ‘What, the one as big as me?’ exclaimed the boy he dispatched to order it; and if we look across Poultry, we can see a cherub, struggling with a similar-sized goose.

Moving westwards we come to the site of the Temple of Mithras, a Persian God of Light whose ‘Dies Nationalis Invicta Solis’ – Birthday of the Invincible Sun – was celebrated on 25 December, a pagan date taken over by the Christians in the fourth century. The cult of Mithras was very popular with the Roman military in this country, so we might like to fancy that Christmas in London began here.

Along Bow Lane now, which during the festive time is decorated with lights, towards the Olde Watling, a pub built by Christopher Wren for his workmen. At this time of year taverns would serve ‘Lambs Wool’, warmed ale containing roasted crab apples, sugar, spices, eggs, thick cream and sippets of bread. Mulled wine and punch were also popular. Dickens always mixed the punch himself. He was a good host, writing out the menus in his own hand and seeing that his guests had a good time. The word ‘punch’ is derived from the Indian word panch or ‘five’, the number of ingredients in a good punch.

After Scrooge’s conversion, he offers Bob Cratchit a bowl of ‘Smoking Bishop’. This was made by baking six Seville oranges, each stuck with five cloves, then placing them in a warmed earthenware bowl, adding sugar, a bottle of Portuguese red wine and leaving the oranges warm for a day. Then the oranges are squeezed, a bottle of port added and the whole heated and served. The colour is then that of a Bishop’s vest.

St Mary-le-Bow is world famous for its bells. Born within the sound you will be a true Cockney. Scrooge delighted in the City’s carillon when he realised he had not missed Christmas Day after all: ‘The churches ringing out the lustiest peal he had ever heard … ding, dong, bell, hammer, clang, clash … glorious, glorious.’

We come out on Cheapside, the old medieval marketplace, and cross to the site of St Peter Cheap, under the tree at the corner of Wood Street. Here we find: ‘A churchyard. Here, then, the wretched man whose name Scrooge was yet to learn, lay … walled in by houses, choked up with too much burying, fat with repleted appetite. A worthy place.’ Discovering his own name there, Scrooge, unmourned and unloved, has his life changed: ‘I will honour Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all the year.’

Crossing St Martin-le-Grand, we see a statue, that of Sir Rowland Hill, outside what was the main Post Office. It was he who in 1840 instituted the Universal Penny Postage, encouraging communication which, a few years later, included the first Christmas card. The stamp on these letters and cards was the ‘Penny Black’ with an image of the young Queen Victoria. It was her consort, Prince Albert, who made popular that ‘pretty German Toy’ – the Christmas tree.

In 1843, Dickens was writing his ‘little book’, as he described it and of which it has been said that it ‘fostered more kind feelings, prompted more positive acts of benevolence.’ A Christmas Carol is forever associated with the season it may, it could be said, have reinvented. True to his own dictum that ‘We should all be children, sometime, and what better time than at Christmas when its Mighty Founder was a child Himself,’ Dickens would enter wholeheartedly into the spirit of the time. He was an expert conjurer; he rehearsed his sons when they came home from school in the plays they would put on for family and friends; and his parties were as joyous as that at the Fezziwigs, with dancing and blind man’s bluff and snapdragon.

Influenced by A Christmas Carol, Victorian philanthropy began to flow into many channels where ‘want is keenly felt’ for, like Scrooge after the visits of the Spirits, Dickens ‘knew how to keep Christmas well’, if any man in the Good Old City of London knew.