Chapter 2

These Ain’t No Baby Blues: PPD, Up Close and Personal

In This Chapter

Recognizing the signs of baby blues

Recognizing the signs of baby blues

Knowing when the baby blues turns into postpartum depression

Knowing when the baby blues turns into postpartum depression

Understanding who’s at high risk

Understanding who’s at high risk

Keeping an eye on dads and adoptive mothers

Keeping an eye on dads and adoptive mothers

Here’s the way your mind works post-delivery: Any depression or anxiety that has been hanging around you in the past, however mild, typically becomes exaggerated. For instance, if you’ve dealt with low-grade depression before, after delivery it can go over the line and become postpartum depression (PPD). Or, if you’ve always had what you thought was a personality quirk of checking twice to make sure the stove burner is off, this “quirk” can become a full-blown obsessive-compulsive episode after delivery.

Research shows that the months both immediately before and after giving birth are the times when women are the most vulnerable for mood disorders. These disorders have various physical, emotional, and psychological causes, one of the primary causes being that dramatic hormone changes occur after delivery. The reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone plummet even below pre-pregnancy levels, to just about zero. Cortisol also increases to high levels by the end of the pregnancy and drops significantly after delivery. These hormones are known to have a major effect on psycho- logical functioning.

Many women, doctors, and postpartum depression researchers think that these dramatic hormonal changes, among others, contribute to postpartum depression, and many women who have postpartum depression seem to be very sensitive to hormonal changes. After delivery, about 80 percent of moms feel the baby blues, which is totally normal. But, if the brain chemistry of a woman is wired so that she already has a tendency toward mood imbalances, she’s at high risk for PPD.

In this chapter, I start out by showing you the differences between PPD and its much milder “cousin,” the baby blues. Then I delve into PPD itself so you can get an idea about its symptoms and timing. I also discuss the risk factors and causes of PPD (to the degree its causes are understood), as well as depression during pregnancy, a subject that’s all too often overlooked.

Baby Blues: Cute Name for a Crummy Time

After pregnancy and birth, new moms often experience a general emotional letdown, along with a huge sense of responsibility for taking care of a newborn infant. They may think, “Why did I do this? Was I nuts?” It’s also not uncommon for new moms to be disappointed by the amount of support they’re receiving (or not receiving, as the case may be), especially when it comes to their partners. On top of all this emotional baggage, new moms face certain undeniable physical challenges too, including tiredness, lack of sleep, and the increased physiological requirements of healing from the birth itself. If she chooses to breastfeed or pump her breast milk for her baby, the mom has a greater requirement for sufficient nutrients, such as protein and iron, that she needs to provide for herself.

What the lighter side looks like

After giving birth, it’s perfectly normal for a woman to have a bout of what has affectionately been labeled “the baby blues.” Research shows that between 50 and 85 percent of all new moms experience the baby blues. It’s interesting to note that the majority of women worldwide seem susceptible to them and, in fact, experience them to some degree. Feelings often include one or more of the following:

Weepiness

Weepiness

Stress

Stress

Vulnerability

Vulnerability

Sadness

Sadness

Worry

Worry

Lack of concentration

Lack of concentration

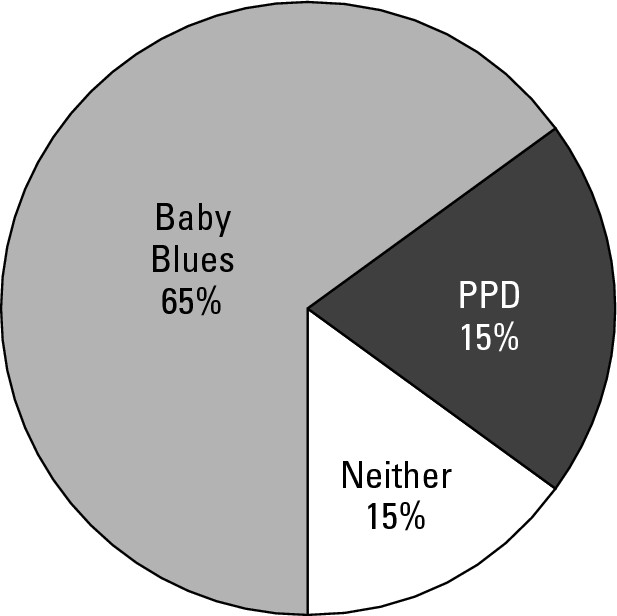

To see how often the baby blues surfaces compared to PPD and a healthy postpartum experience, see Figure 2-1.

|

Figure 2-1: The occurrence of the baby blues, PPD, and a healthy postpartum experience. |

|

.jpg)

Getting support

Even though no research proves whether a highly supportive partner and social network help a new mom shake off baby blues more quickly than without them, it certainly makes sense that when a woman faces biochemical and emotional challenges, having a supportive partner and family environment makes life a lot easier for her.

Along with family support, all new moms need to have some basic education and information about the baby blues, if only to know that the condition isn’t likely to last long and to help her distinguish them from PPD (see the upcoming section “Distinguishing between baby blues and PPD”).

When the Misty Blues Turn to Darker Hues

If you’ve been waiting for a few weeks for your baby blues to go away and they’re still hanging around, or if you’re unable to identify with other women in your support group because your blues just seem to feel worse than theirs, you may be dealing with something other than the mild baby blues. More than likely you’re suffering from the more severe, but completely treatable, PPD. If you’re not sure, don’t worry, you’ve come to the right place. In this section, I help you determine what you’re suffering from.

Distinguishing between baby blues and PPD

PPD and the baby blues look similar in some ways: They both involve some kind of low mood, worry, and feelings of sadness and irritability, and they both affect new moms. But, PPD is a more serious condition that requires a whole different level of intervention than the baby blues. Because of the seriousness of PPD, you need to know how to tell the difference between the two so you can get help as soon as possible.

Here are two basic ways to differentiate the baby blues from PPD:

Duration of the symptoms: The first way to tell the difference is by noting how long your symptoms last — regardless of how mild they seem to be. Anything past two (or at the most, three) weeks, even if you feel only mildly blue, is now considered to be PPD.

Duration of the symptoms: The first way to tell the difference is by noting how long your symptoms last — regardless of how mild they seem to be. Anything past two (or at the most, three) weeks, even if you feel only mildly blue, is now considered to be PPD.

Often a woman will feel down, stressed, and emotional for months and tell herself (and her partner, family, and friends) that she just has a case of the baby blues and that her feelings aren’t bad enough to get help. Don’t wait and assume that your feelings will eventually go away. Ignoring your symptoms for such an extended period only prolongs your condition and makes recovery more difficult. In fact, sometimes the baby blues hang on for the long haul and spiral down into more serious PPD symptoms.

Severity of the symptoms: If, as a new mom, your symptoms interfere with your daily life in a big way, you may be suffering from PPD or another postpartum mood disorder (see Chapter 3 for details on the other disorders).

Severity of the symptoms: If, as a new mom, your symptoms interfere with your daily life in a big way, you may be suffering from PPD or another postpartum mood disorder (see Chapter 3 for details on the other disorders).

If your symptoms are in fact strong enough to affect your daily life, you need to contact a professional, even if it happens to overlap the baby blues timing of the first two weeks (or so) after pregnancy. The sooner you get help, the better.

In my own case, after the placenta was delivered and my internal hormones radically shifted, I immediately plummeted into a severe case of depression. In other words, as soon as the pregnancy hormones left my body, I found myself at the bottom of a deep psychological well and knew that something was terribly wrong.

Also helpful in distinguishing between PPD and baby blues is perspective. For example, whereas a mom with the normal baby blues typically has a perspective about becoming herself again, a woman with PPD usually loses that perspective. PPD is a thief — it steals away the woman’s perspective and her feelings of competence and confidence. Generally, women with PPD feel as if they’ve lost themselves.

The question to ask yourself is this: “Do I generally feel like myself?” If the answer is “Well, I’m tired because I’m up with the baby a lot, and sometimes I cry for no reason, but yes, I’m still me,” you have a case of the baby blues. If you answer the question with something like, “No, I don’t know who this is, but it’s not me,” you’re probably looking at PPD.

If you do feel as if you may be facing PPD, no matter what anyone tells you, don’t wait to get help. If you’re feeling that bad (or if you know a new mom who is feeling that bad), by golly, it may be PPD and help is needed now. If it turns out not to be PPD, no harm is done. The worst that happens is that help is sought, the new mom finds out it’s the baby blues, and she leaves the therapist’s office with a plan of action. And usually she starts feeling better right away.

.jpg)

You’re unable to function normally

You’re unable to function normally

You’re feeling sad, angry, anxious, or scared for much of the day

You’re feeling sad, angry, anxious, or scared for much of the day

You can’t cope with everyday life

You can’t cope with everyday life

You have scary thoughts (refer to Chapter 3 for much more on scary thoughts)

You have scary thoughts (refer to Chapter 3 for much more on scary thoughts)

Identifying the symptoms of PPD

The symptoms of PPD, and the severity of those symptoms, differ greatly from woman to woman. But even one of the following symptoms, no matter what the magnitude, may signal that you’re suffering from PPD.

Sleeping too much or inability to sleep at night, even when you’re not up with your baby

Sleeping too much or inability to sleep at night, even when you’re not up with your baby

Irritability, anger, or rage

Irritability, anger, or rage

Worrying much of the time

Worrying much of the time

Feeling overwhelmed or anxious

Feeling overwhelmed or anxious

Difficulty making even minor decisions

Difficulty making even minor decisions

Problems concentrating and lack of focus

Problems concentrating and lack of focus

Change in appetite (usually loss of, but sometimes the opposite)

Change in appetite (usually loss of, but sometimes the opposite)

Overeating or binging on carbs and sugar

Overeating or binging on carbs and sugar

Loss of sex drive

Loss of sex drive

Sad a majority of the time

Sad a majority of the time

Guilty feelings

Guilty feelings

Low self-esteem or feelings of worthlessness

Low self-esteem or feelings of worthlessness

Hopelessness

Hopelessness

Inability to experience pleasure

Inability to experience pleasure

Discomfort with the baby (uncomfortable holding or interacting with the baby)

Discomfort with the baby (uncomfortable holding or interacting with the baby)

Physical problems without apparent cause (backaches or other pains that the doctor can’t figure out)

Physical problems without apparent cause (backaches or other pains that the doctor can’t figure out)

I’ve often heard women lament that they’ve never really felt like themselves since the birth of a previous child. Sometimes this fact isn’t clear to them until they begin to get help for their current bout of PPD. It usually turns out that they suffered PPD after the birth of another child, but they never received adequate help. Even though it can be a bit tougher to get rid of this depression that’s been hanging on for years, the good news is that these women can still return to their old selves.

Given this general lack of confusion, it’s extremely important to conduct individual assessments of new moms who may be suffering from PPD so that those women who are indeed afflicted can receive treatment and intervention as early as possible. If PPD goes untreated, it can become chronic depression — 25 percent of moms are still depressed after one year.

Understanding the risk factors

PPD can occur after the birth of any child, regardless of the baby’s gender or place in the birth order. A popular misconception about PPD is that if it’s going to happen, it will happen after the first baby. But, this belief isn’t necessarily true. Many women who show up in my support groups or in my office are flabbergasted that they, in fact, didn’t have any depression after their first child but they did with a later baby. Doctors don’t know why this happens, but be aware that it does.

Your OB (or another professional that you’re in contact with) should have already given you proper PPD information and should have alerted you if you’re at high risk. The strongest predictors of PPD are depression and anxiety during pregnancy (about one third of all postpartum mood disorders start during pregnancy). And, whether you’re at high risk or not, someone in your OB’s office (or wherever you received prenatal care) should have screened you for PPD during and after pregnancy. If you haven’t been screened, you can use the information in this chapter to self-screen. But, also remember to ask the OB (or other medical practitioner) to screen you in the office.

A few factors make it more likely that you will suffer from, or are already suffering from, PPD. The more risk factors that apply to you, the more at risk you are. Ask yourself the following questions to assess your risk factors:

□ Did you have PPD after the birth of another child?

□ Were you anxious or depressed during your pregnancy, especially during the third trimester?

□ Have you ever had PMS or PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder)?

□ Have you ever suffered from mood changes while taking birth control pills or fertility medication?

□ Do you have a personal or family history of depression or anxiety?

□ Have you ever had an eating disorder?

□ Do you have good physical and emotional support?

If you answered yes to any of the preceding questions, you’re at risk for experiencing PPD. Hormonal changes are a big factor. If you have ever had PMS or PMDD or have struggled with mood swings from hormone medication, you’re more likely to react strongly to hormonal changes, which means that the changes due to childbirth may make the suffering more intense. Also, a woman’s perceived support — both of the physical kind (someone doing chores, making her food, and so on) and the emotional kind (someone to talk to and lean on) is crucial for a healthy postpartum period. If she feels alone and unsupported, she’s at high risk for PPD.

The rates of depression during and after pregnancy are also higher among women with eating disorders, especially bulimia and binge-eating. Perfectionism, which is the fear of making mistakes, seems to be a factor linking eating disorders to PPD. Interestingly, women with eating disorders are at just as high a risk for developing PPD as women who have a history of depression. (A personal history of depression raises the new mom’s risk of PPD to 30 percent.)

.jpg)

The thyroid factor

About 10 percent of new moms develop postpartum thyroiditis, which means that the thyroid gland is inflamed. This condition can result in temporary hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) or hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid). Some of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism are weight loss, anxiety, panic attacks, and insomnia. Symptoms of hypothyroidism are tiredness, depression, weight gain, and loss of memory. Sometimes postpartum thyroiditis goes away on its own, but for others it can turn into chronic thyroiditis.

Because this condition is so common, if I had my way, every new mother would be tested between two and three months postpartum just to rule it out. If she’s depressed due to a thyroid imbalance, all the antidepressants and therapy in the world wouldn’t fix it. The thyroid imbalance needs to be addressed directly — nutritionally, with alternative medicine, or with prescription medication (or a combination of all the options).

Especially if you have a family history of thyroid imbalance, ask your doctor (preferably an endocrinologist) to test your TSH, T4, anti-TPO, and antithyroglobulin. The last two test your antibodies, which may be too high (indicating an imbalance) even if the first two are within normal range.

Traveling in time and place

As medical science becomes more enlightened, it doesn’t embrace and promote as radical a split between mind and body as it used to. Now medicine is starting to put forth a more integral, useful, and usable definition of PPD. More and more medical doctors, healthcare providers, and caring professionals in all disciplines are now informed about PPD. Recent legislation in some states is increasing awareness of those working with pregnant and postpartum women so that many more doctors are conducting at least preliminary screenings for maternal depression. More than 60 percent of moms who get PPD have an onset of PPD within the first six weeks following delivery.

In other countries, the general level of knowledge about PPD is far ahead of what’s found in the United States. In France, England, Australia, and Canada, for instance, the detection and assessment of PPD is considered a priority. In Canada, at the very first well-baby check, the doctor notes any sign of depression on the part of the mom and sends her to a clinic for help.

When you’re well and have the strength to participate in this important and growing movement, as a member of Postpartum Support International, you can join hundreds of other passionate individuals to help promote legislation, education, and resources for postpartum women and their families. Check out the following Web site for details: www.postpartum.net.

Considering Special Situations Where PPD May Be on the Horizon

No one is immune to PPD. It can happen to anyone — even dads and women who didn’t give birth. And in addition to the high risk factors already discussed earlier in this chapter, there are specific situations that make parents especially vulnerable. These specific situations are highlighted in this section.

If Baby is seriously ill

Having a baby with serious health challenges is no picnic, and unfortunately, these challenges can cause moms to spiral into PPD. These moms are often tending to their ailing infants so much that they pretty much ignore their own needs — eating, sleeping, and taking breaks, for starters. Moms with babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) are prime examples. Often these moms, no matter how strongly they’re urged to contact me, choose not to until they’re literally falling over and unable to function. They practically live at the hospital and they’re constantly wracked with guilt. They’re thinking, “If I would have done things differently, my baby would be fine. It’s my fault that he’s suffering.” Nurses practically have to kick these moms out of the NICU to go home.

When a mom of a child born with disabilities sees other babies leave the hospital thriving, she’s left with the sinking feeling of knowing that her child’s health issues may always be a factor in her and her child’s life. When the baby is well enough to come home, no matter what the health challenge was or still is, it’s often then that mom crashes. She’s filled with anxiety about taking care of her fragile child and continues to put her needs last (if she even recognizes them at all).

It’s harder for you than it is for her.

It’s harder for you than it is for her.

Your baby needs you to have the strength to care for her when she comes home (finally). So, make time to eat and sleep.

Your baby needs you to have the strength to care for her when she comes home (finally). So, make time to eat and sleep.

Take breaks away from the hospital.

Take breaks away from the hospital.

If you have other children, spend time with them — they need you, too.

If you have other children, spend time with them — they need you, too.

Remember that it’s not your fault.

Remember that it’s not your fault.

Lean on your partner or a therapist, friend, or other support person.

Lean on your partner or a therapist, friend, or other support person.

Many of my clients throughout the years are mothers of children with various disabilities (it has helped tremendously that my first career was in the field of special education). Counseling and support groups for them and their partners can be extremely helpful so they meet other moms and parents in similar situations and receive tools to help with their grief and plans for the future.

If Baby passes on

It’s a cruel fact that even when a pregnancy ends without a live baby to show for it, PPD can still rear its ugly head. All the body “knows” is that it’s no longer pregnant. No matter why or how the pregnancy was terminated — by nature or by human choice — the symptoms of PPD are often present. The mom usually has some level of grief due to the loss of her baby, but she can also experience a biochemical reaction of her pregnancy hormones dropping, which can cause PPD.

A significant percentage of women experience high levels of anxiety after a miscarriage for about six months, and they’re also at increased risk for obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Men, even though they grieve differently than women, can also experience depression and anxiety following a termination. Resolve is an organization that specifically helps with the painful subject of infertility — whether it’s the inability to get pregnant or the inability to stay pregnant. Check out this helpful resource at www.resolve.org .

With her next pregnancy and postpartum period, a woman needs to be monitored for anxiety and depression because it’s normal for her feelings to surface at this time (she may be depressed about her last loss, anxious about losing this one too, guilty about being happy, and so on).

Different types of support groups are also available, and these professional organizations can often point you in the direction of an appropriate group that specifically fits the type of loss you’ve experienced — miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal death including SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome), or any other situation where the death of a baby occurs.

If babies come in pairs (or more)

More than 25 percent of mothers of multiples have depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy and after delivery. Some of the reasons for this high percentage of depression and anxiety include the following:

The high rate of preterm deliveries: Mothers of preterm infants experience a higher level of depression than mothers of full-term infants, and multiples are notorious for being born preterm.

The high rate of preterm deliveries: Mothers of preterm infants experience a higher level of depression than mothers of full-term infants, and multiples are notorious for being born preterm.

Sleep deprivation: It’s difficult enough getting the sleep you need with a single screaming baby, let alone with many mouths crying and eating throughout the night.

Sleep deprivation: It’s difficult enough getting the sleep you need with a single screaming baby, let alone with many mouths crying and eating throughout the night.

Social isolation: Because organizing yourself, the babies, and all of the baby stuff takes so much work, it’s challenging to meet anyone out of the house. Many moms of multiples feel that it’s just not worth it.

Social isolation: Because organizing yourself, the babies, and all of the baby stuff takes so much work, it’s challenging to meet anyone out of the house. Many moms of multiples feel that it’s just not worth it.

The never-ending demands of the babies: When one’s napping, the other one’s screaming, and at least for a while, sleeping and feeding schedules are close to impossible (and maybe not your style or choice). And if you’re breastfeeding or pumping, you’ll feel like a continuous milk machine.

The never-ending demands of the babies: When one’s napping, the other one’s screaming, and at least for a while, sleeping and feeding schedules are close to impossible (and maybe not your style or choice). And if you’re breastfeeding or pumping, you’ll feel like a continuous milk machine.

If you’re a teenage mom

Young mothers — under the age of 19 — have an extremely high risk (as much as 48 percent) of becoming depressed postpartum. Two of the main reasons are isolation and lack of support. Think of it this way: Their parents often kick them out of the house, the fathers of their babies take off, and their friends are busy living regular teenage lives. As you can see, PPD affects the teenage mom’s ability to have relationships, which, in turn, lowers her self-esteem even more.

Like their adult counterparts, these moms often cry, are lonely and sad, have difficulty sleeping, and experience mood swings. But some symptoms are more unique to teenage moms. For example, many teen moms with PPD are scared and feel unprepared for motherhood. They also feel torn between the responsibilities of motherhood and being a teenager, and they may fear being abandoned or rejected by friends and family. Because their world is different from the adult reality and because they often can’t identify with adult moms with PPD, teen moms desperately need their own support groups to help their isolation — whether they’re in-school groups or community groups.

Extending beyond Biological Moms: PPD in Dads and Adoptive Moms

Just as PPD in moms that deliver their babies is becoming well-accepted and much more understood, news is suddenly cropping up about PPD in people who didn’t actually birth their babies. This is confusing and odd for many people to grasp. Even though it isn’t really a funny fact, many folks are surprised and sometimes humored that postpartum dads get depressed too. And women who adopt babies are also at risk. This section explains.

Letting go of preconceptions: Dads with PPD

Men, too, have PPD after their babies are born, and it’s at the rate of at least 10 percent. Their symptoms are different from the fluctuating moods and emotions that moms with PPD exhibit. Fathers seem to have more tension and short-temperedness as the main symptoms of their PPD. Other feelings are confusion, fear, anger, frustration, and helplessness. Fathers with PPD are concerned about their partners, their disrupted family life, and their financial problems. They also have increased expectations for themselves, decreased sleep, confusion over their new role, and increased responsibilities (if the mother has PPD or is otherwise ill). It’s assumed, for obvious reasons, that a dad’s depression isn’t hormonally induced.

The strongest predictor of whether a father will become depressed postpartum is the presence of PPD in the mother. The father whose partner has PPD has between a 24 to 50 percent chance of developing PPD symptoms. The other factors that put dads in the high-risk category are previous bouts of depression and instability in the relationships with their partners. It’s interesting to note that the onset of a father’s depression occurs later in the postpartum period than the onset of PPD in moms. In Chapter 16, I discuss why partners, if the partners weren’t receiving adequate help themselves, sometimes become depressed as the moms recover.

While working with moms, I often suggest that their partners accompany them to a therapy session. During that session I check in with the partners to make sure they’re receiving the support that they need. I can tell if a dad is depressed, no matter how he tries to cover it up with statements such as “I’m just here for her — I’m fine.” Sometimes (but more rarely) a dad has the awareness to know he’s suffering and will call me directly to ask for an appointment.

Even though this is changing for the better, men often avoid going to support groups. But, they’re usually willing to talk on the phone with another dad who’s “been there.” Even if that’s all he does, it will be helpful. Your therapist may have a reference — person or Web site — for him, so be sure to ask. Two of the many good Web sites for postpartum dads are www.postpartumdads.org and www.postpartum.net/fathers.html .

Feeling the weight without the labor: Adoptive moms

These moms have a difficult time when they’re hit with PPD because they usually aren’t given permission (by themselves or by others) to feel depressed after finally having a baby. They feel and hear things such as, “Isn’t having a baby what you’ve wanted all these years? How can you complain about anything now?” Or, “You’ve spent all your savings, energy, and time on this project, so you should just be happy.”

Because these moms typically aren’t screened in OB offices, other professionals, such as pediatricians, family practice doctors, and adoption agencies need to be on the lookout for symptoms of depression. These professionals also need to understand that it’s difficult enough for a mom with PPD who delivered her baby to acknowledge that she’s in distress because she’s afraid that her baby will be taken away. So, they need to take into consideration the fear of adoptive moms who, for good reason, often have that worry to begin with.

The sudden impact of becoming a mother — often the primary caretaker — may also be a factor in PPD, as well as the sleep deprivation that accompanies having an infant in the home.