CHAPTER ELEVEN

Crying in the Wilderness

You have been a “voice crying in the wilderness,” but I believe that you are going to be well pleased with the following.

—Mississippi judge Tom P. Brady to Louis E. Faulkner, July 18, 1955

October 8, 1949, marked a day of transition in Hattiesburg. On that Saturday afternoon, hundreds of local white citizens gathered beneath a cloudy sky at Oaklawn Cemetery for the burial of W. S. F. Tatum. Having first arrived in Hattiesburg in 1893 “looking for pine trees,” Tatum had for more than fifty years played an enormous role in shaping local life. He was a two-time mayor, a major municipal investor, and a benefactor of dozens of white churches, schools, and civic organizations. When news of Tatum’s death became public, Hattiesburg’s mayor issued a special proclamation declaring a “day of mourning” and ordered the closure of all municipal offices to commemorate the passing of Hattiesburg’s preeminent pioneer.1

Meanwhile, a celebration raged across town. That Saturday marked homecoming at Mississippi Southern College. Festivities began that morning with a parade that “splashed color” across the downtown, noted one reporter. Thousands of local residents filled downtown sidewalks and crowded into the windows of office buildings to watch the lively procession. Student organizations competed for prizes awarded to the most attractive or most inventive parade floats. The Kappa Alpha fraternity received an award for a float featuring a pretty female student sitting in a champagne glass filled with balloons made to look like bubbles. Chi Omega won the sorority prize for a float adorned with twelve hundred homemade golden paper flowers.2

Filled with cheer and vigor, the day-long fete featured student and alumni lunches, campus tours, open houses at the student lounge and the Pan-Hellenic Council, an afternoon tea at the Home Economics Department, smokers hosted by an athletic booster club and the Hattiesburg Junior Chamber of Commerce, two dances, and, of course, the football game. That evening, ten thousand raucous fans watched the Mississippi Southern College Southerners dismantle the McMurray College Indians by a score of 55–32.3

The featured guest of the 1949 Mississippi Southern College Homecoming Ceremony was the enormously popular Mississippi governor Fielding Wright. Wright led the morning parade and attended that evening’s football game. A longtime politician from the Mississippi Delta, Wright was lieutenant governor in 1946 when the governor died and left him the office. Wright was reelected the following year, bucking a longstanding state political trend by becoming the first governor-elect from the Delta region in over thirty years. In Forrest County, he even beat out Hattiesburg native Paul B. Johnson Jr. in that summer’s primary.4

Governor Wright was not a racial demagogue in the mold of Theodore Bilbo, but like all the state’s leading politicians of the time, he was an ardent and outspoken white supremacist. As with the senatorial campaign of 1947, each major gubernatorial candidate ran on a platform vowing to maintain Mississippi’s racial hierarchy amid perceived threats to Jim Crow.

In Governor Wright’s 1948 Inaugural Address, he criticized what he considered to be “anti-Southern legislation” proposed by Northern Democrats. According to Wright, these included the “FEPC, anti-lynching legislation, anti-poll tax bills, and now the anti-segregation proposals.” These proposals, Wright charged, promised to “eventually destroy this nation and all the freedoms which we have long cherished and maintained.”5

By 1948, white Southern segregationist Democrats did indeed have cause for concern. On February 2, 1948, President Harry Truman delivered a civil rights message to Congress, calling for federal anti-lynching legislation and greater protections for African Americans’ civil and voting rights. Northern Democrats were joined by Republican leaders in the North and West who also advocated for increased civil rights for African Americans. Later that summer, the Republican Party national platform included calls for anti-lynching legislation, the abolition of poll taxes, the end of racial segregation in the armed forces, and federal legislation to ensure that “equal opportunity to work and to advance in life should never be limited in any individual because of race, religion, color, or country of origin.”6

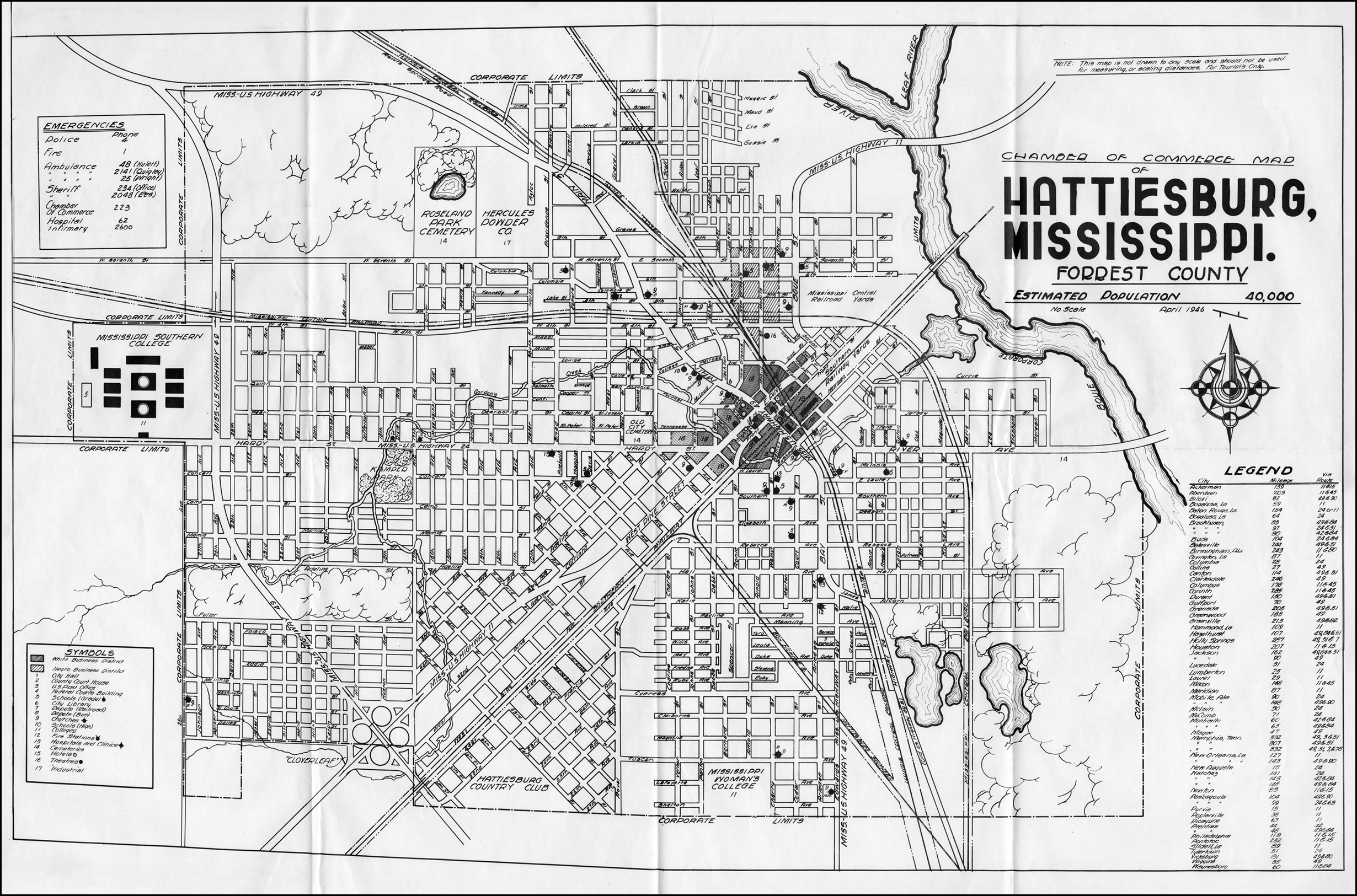

Map of Hattiesburg, 1946, produced by the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce. The “White Business District” is indicated with heavy cross-hatching, and the “Negro Business District” by light cross-hatching. (McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi)

Bear in mind that none of this was particularly radical. Every component of these proposals fell within the basic framework of constitutional rights already guaranteed to American citizens. The problem was that the federal government had not genuinely protected the individual liberties of black Southerners since the 1870s. This civil rights advocacy of the 1940s was significant because it symbolized the greatest support for Southern black rights by Northern politicians since Reconstruction.

There were several factors behind the timing of such support. First and foremost was the plain fact that Jim Crow–era disfranchisement was an undeniable contradiction to the foundations on which American democracy was purported to have been built; this basic detail cannot be overlooked. Black people in the Jim Crow South were expected to pay taxes and abide by laws without having any ability to vote for representatives who might serve their interests.

Second was the expanding political influence of a Northern black electorate. The black migration that began in the 1910s accelerated once again during World War II, bringing hundreds of thousands of new black voters into Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and elsewhere. During the 1940s, nearly three hundred thousand African Americans left Mississippi alone. These newly enfranchised black voters helped elect several African Americans to Congress and increased pressure on Northern white politicians to support black civil rights in the North and South. Any white politician running for a major office in New York, for example, needed to consider the potential effects of the black vote.7

Another factor was the glaring hypocrisies on the international stage between the rhetoric of American democracy and the realities of Southern Jim Crow. As the United States claimed to be the world’s greatest purveyor of freedom and democracy during the early years of the Cold War, Southern racial violence, disfranchisement, and segregation threatened to undermine the country’s purported commitment to liberalism and self-determination. Southern Jim Crow created an obvious conundrum with global implications: if people within America’s own borders could not vote because of their skin color, then how could people in the nations of Africa, Asia, and South America possibly view the United States as the world’s leading democracy?8

A fourth major factor was the collection of racially progressive precedents—especially the FEPC (Fair Employment Practices Committee), the “Black Cabinet,” anti-discrimination clauses in New Deal programs, and Smith v. Allwright—that were enacted during the Roosevelt Administration. New Deal policies often worked in sync with Southern Jim Crow, but in the postwar years, Northern New Deal Democrats, including Eleanor Roosevelt, continued to expand their vision of a greater federal role in enhancing individual freedom and opportunity in American life. As the reach of the federal government continued to broaden through the 1930s and 1940s, there appeared to be significant national interest in supporting the basic civil rights of African Americans. Of course, white Southern segregationists viewed these developments as serious threats to the foundations of institutionalized white supremacy.9

Less than two weeks after President Truman’s civil rights address, Mississippi governor Fielding Wright called a meeting of state legislators and other influential white leaders. With approximately five thousand “true white Jeffersonian democrats” in attendance, the meeting opened with rebel yells, Confederate flag waving, and a loud rendition of “Dixie,” the Confederate States of America’s unofficial national anthem. The group denounced all components of President Truman’s civil rights message to Congress and adopted a resolution warning the National Democratic Party that Mississippi legislators would “make every effort within the party to defeat such proposals,” even if they had to “nominate our own candidate for president and vice president and throw our electoral vote to those men,” asserted House Speaker Walter Sillers.10

Eight days later, on February 20, fifty Southern Democrats in the United States House of Representatives met in Washington, DC, where according to the Associated Press, they “declared war today on President Truman’s civil rights program” and adopted their own resolution expressing concern over “an invasion of the sovereignity [sic] of the states.” The following day, Democratic leaders from ten Southern states gathered in Jackson, where they also adopted resolutions outlining a break with the national Democratic Party and the formation of a new “States’ Rights” political party. After decades of unflinching loyalty, these white Southern Democrats stood ready to abandon the political party of their forebears.11

Despite Governor Wright’s warning that federal overreach threatened “to tear down and disrupt our institutions and our way of life,” by the late 1940s, nearly two decades of federal spending had saved Mississippi from utter destitution and generated the best economic conditions in the history of the state. First came the New Deal of the 1930s and 1940s, which created tens of thousands of jobs and injected an immeasurable amount of capital into the state’s payroll and infrastructure. Then came the federal wartime spending of the 1940s, which created unprecedented statewide economic growth. Although most of Mississippi’s wartime boom was concentrated at Camp Shelby, Kessler Field in Biloxi, and the Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula, the economic benefits of wartime mobilization touched every corner of the state. Smaller military installations and federal contracts boosted the economy of several additional cities. And thousands of Mississippians flocked to Camp Shelby and the shipyards on the Gulf Coast for temporary jobs. Between 1940 and 1946, Mississippi’s annual per capita income nearly tripled, increasing from $218 to $605. Mississippi remained one of the poorest states in America, but federal spending over the preceding decades ensured a level of stability unimaginable just twenty years earlier during the onset of the Great Depression.12

It is important to understand that the Southern dogma of states’ rights as it was employed in 1948 was both a ruse and a logical fallacy. Beyond issues related to race, Southern Democrats showed little concern over federalism or Northern involvement in Southern affairs. In fact, many of them and their constituencies had not only supported the New Deal of the 1930s but had also actively sought to expand federal programs and spending in their states. Furthermore, no white Southern elected official could accurately claim to represent the entire citizenry of their state. African American residents comprised enormous portions of the population in every state in the Deep South and factored into the calculations that determined the number of congressional representatives each state was assigned. Yet most black people were completely blocked from political participation. In reality, Southern states’-rights politicians represented the rights and interests of white residents only. State sovereignty was of little concern to states’-rights advocates in 1948. The real concern was the ability of white Southerners to maintain white supremacy by continuing to violate the constitutional rights of African Americans.13

In any case, during the 1948 presidential election, white Southern Democrats formed a new political party called the States’ Rights Democrats and left the national Democratic Party for the first time in a presidential election since Reconstruction. Also known as the Dixiecrats, these white Southern legislators nominated South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond for president and Mississippi governor Fielding Wright for vice president.14

As might be expected, the Dixiecrats were enormously popular among white Mississippi voters, carrying 87 percent of the popular vote in the 1948 presidential election. They performed even better in Hattiesburg. Local attorneys Stanton Hall and Dudley Conner helped lead a get-out-the-vote campaign, and the Hattiesburg American offered free transportation to the polls while encouraging local whites to cast ballots “against indignities proposed against the South.” A record turnout in Forrest County supported the Dixiecrat ticket with over 90 percent of the vote.15

Although the Dixiecrats captured approximately one-fifth of the popular vote in the South, the party ultimately failed to achieve its broader goals. Struggling to secure financial contributions and develop broad grassroots support, the Dixiecrats won only four Southern states in the general election—Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana—and did not significantly alter the 1948 Democratic Party platform. Nonetheless, the movement was important for several reasons. Representing the first time since Reconstruction that the South had not voted solidly Democratic, the Dixiecrat movement demonstrated an unprecedented level of partisan flexibility in the region. Remember that Democratic president Franklin Roosevelt of New York had carried at least 93 percent of the popular vote in Mississippi during each of the previous four elections. No Democratic presidential candidate has ever again approached such broad support in the Deep South. The Democratic Party recaptured each of the Dixiecrat states in 1952, but the Dixiecrat revolt of 1948 symbolized a clear fracture in the New Deal political coalition of the 1930s and 1940s.16

The Dixiecrat movement also demonstrated once again the immense political capital available to white Southern politicians who explicitly resisted any threat to Jim Crow. In hindsight, it is easy enough to condemn the Dixiecrats’ most famous racial demagogues. But we must not forget the people who voted for them. In the late 1940s, it would have been obvious to any Southern politician that hysteria and hardline defiance created widespread political appeal among white voters. As the South prepared to enter its most prosperous era, white Southerners stood ready to defend racial supremacy. In Hattiesburg and elsewhere, the most defiant politicians—Fielding Wright among them—were regarded as heroes. And as heroes, they were invited to events like the Mississippi Southern College Homecoming.17

Less than three weeks after the war ended, the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce launched an initiative called the “Post-War Development Fund” to avoid what the Hattiesburg American labeled a potentially “disastrous post-war slump.” With Shelby demobilizing, the organization once again turned its attention to recruiting new manufacturing firms. Previous experience in pursuing industries had shown that interested firms might require the city to provide land, buildings, tax credits, equipment, or subsidies. The Chamber of Commerce postwar development fund was conceived in anticipation of these expenses. The plan was to collect enough capital from local businesses to purchase $75,000 worth of United States Treasury Bonds. The bonds were a conservative yet lucrative investment. They promised to generate yearly interest and could be sold as needed to obtain liquid capital.18

The effort to attract new industries was widespread across Mississippi. Aided by a newly formed Mississippi Agricultural and Industrial Board, dozens of cities across the state successfully attracted new industries in the years after World War II. The Magnolia State never became a major manufacturing center, but it did enjoy significant industrial growth. In 1939, Mississippi had 1,235 manufacturing establishments that paid a total of $27.1 million in wages. Eight years later, the state had 1,985 firms that paid $116.2 million in wages. By 1954, Mississippi’s manufacturing establishments numbered 2,252 with a total payroll of $188.8 million. In a state with an essentially static population over those same years, the wages paid by manufacturing establishments increased by an inflation-adjusted factor of three.19

Similar growth occurred throughout the South. Much of that development took place in major cities such as Atlanta or Birmingham, but industrial growth also touched hundreds of mid-sized Southern towns that attracted new industries by offering state-supported development bonds, tax exemptions, and the promise of cheap labor. Between 1939 and 1954, the number of manufacturing establishments in the six Southern states of Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Tennessee expanded from 11,391 to 21,756, a 90 percent increase that created over 466,000 jobs in all corners of those six states.20

The Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce, its members flush from the wartime boom, met its goal for the postwar development fund in less than two months. “It was [an] appropriate and proper time to put on a drive,” explained the Chamber of Commerce president, “as practically every business house in Hattiesburg had prospered tremendously from the activities of Camp Shelby.” Contributions ranging between $5 and $1,500 poured in from every type of business—bakeries, groceries, restaurants, banks, contractors, theatres, chain stores, cleaners, law offices, doctor’s offices, and automobile dealers. In less than sixty days, the campaign closed with $91,886.50 “to be used EXCLUSIVELY,” noted a Chamber of Commerce report, “in the development of industrial and agricultural activities.” The organization purchased $75,000 in United States Treasury Bonds and invested the remainder in two local banks.21

Board of directors of the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce, 1947. Louis Faulkner is seated in the lower-right-hand corner. (McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi)

The growth of Hattiesburg’s postwar development fund was enabled almost entirely by federal spending. New Deal programs notwithstanding, the federal government between 1940 and 1945 poured tens of millions of dollars into Camp Shelby, creating thousands of local jobs and paying the salaries of hundreds of thousands of troops who spent their earnings across the city. The white business owners who profited most handsomely from this economic boom then contributed a portion of their profits into a fund that was used to purchase federally insured treasury bonds.22

Before Shelby mobilized in 1940, the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce was powerless to save the city’s crumbling economy. As the Hattiesburg American bluntly observed of the prewar era, “The Chamber of Commerce was broke.” Then came Shelby’s salvation. “This community,” observed the local paper in 1945, “has been blessed, economically, as few others in the nation have been blessed.”23

In 1946, the Chamber of Commerce went to work with over $93,000. Members identified a number of strategies to secure future prosperity: establishing Camp Shelby as a permanent military training center, recruiting new industries, developing more local farms, and establishing a new airport. Despite their best efforts, most of these goals failed to come to fruition.24

Camp Shelby demobilized in 1946 and did not again play a significant role in the local economy for nearly fifty years. The federal government did spend roughly $3 million in 1953 to prepare the site for troop training during the Korean War, but the base was never activated for deployments. And although Shelby became a permanent military establishment in 1956, it did not host a large number of troops until the late twentieth century. During the Vietnam War, only one brigade deployed from Shelby. In more recent years, Shelby has once again become a major military installation, offering similar benefits to Hattiesburg as it did during World War II. But for most of the postwar era, Camp Shelby remained a “ghost town,” as one National Guardsman dubbed the site in 1947. As the 1940s came to a close, it became clear that new jobs and revenues would have to come from elsewhere.25

The effort to recruit new industries also met limited success. The Chamber of Commerce spent much of the late 1940s gauging the interest of dozens of companies across the United States. In 1947, the organization sent representatives on a long road-trip through Tennessee, Missouri, and Illinois to meet with officials from some thirty companies about plans for future plant locations. The Hattiesburg representatives seemed optimistic, but nearly all of these interactions appear to have been nothing more than courtesy meetings. Attracting new industries in the postwar era was more difficult than they had anticipated. Their challenges were rooted in a combination of increased competition and lack of capital.26

With virtually every Southern city interested in attracting new firms, Hattiesburg promoters were often simply too late. On several occasions, Chamber of Commerce representatives met with company officials only to learn that the particular firm was already in negotiations with cities such as Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Gulfport, Mississippi; Monroe, Louisiana; Greenville, Mississippi; Savannah, Georgia; Dallas, Texas; or, in one case, “a little town in Alabama.”27

The other major problem was that companies required too much of the city. Increased competition for factories led to increased subsidies, tax credits, land, and buildings required by companies. None of these requirements was necessarily new. In fact, the Chamber of Commerce’s postwar development fund was created in anticipation of such requests. But the organization was not prepared to contend in the highly competitive postwar era. They simply did not have the capital.28

In 1947, the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce entered negotiations with the National Gypsum Company, a wallboard manufacturing firm based in Buffalo, New York. National Gypsum was seeking a site for a new factory that would annually employ over 450 people and contribute an estimated $2 million to the local economy. But the firm also asked the city of Hattiesburg to donate land for the new factory and provide at least $2.5 million to subsidize half the construction costs. Hattiesburg’s entire operating budget in 1946 was only $207,805, and the city already had a bonded indebtedness—for libraries, schools, parks, and sewers, among other public projects—of over $1.4 million. After some talk of a municipal bond referendum, the organization ultimately realized it could not proceed. Even with their postwar development fund, this was simply far beyond their range of affordability.29

Such limitations prevented Hattiesburg from developing into a major industrial center, but the city was able to add some jobs. In 1946, the Chamber of Commerce used portions of the postwar development fund to organize a small farming cooperative that marketed agricultural products. In addition, the economic recovery of the war years enabled the foundation or expansion of several small firms, including Hattiesburg Concrete Products, Dixie Pine Products, American Sand & Gravel Company, Burkett Sheet Metal Works, Gilkey’s Welding and Boiler Works, and Roby & Anderson Machine Works. Other jobs were offered at automobile service stations, grocery stores, cleaners, electric companies, building contractors, plumbing firms, and retail stores. And the city still had some larger employers from the prewar era that expanded during and after the war. These existing firms were their greatest asset.30

For most of the late 1940s and 1950s, Hattiesburg’s largest employer was the Reliance Manufacturing Company. Having first opened its Hattiesburg plants in 1933, the Chicago-based firm profited handsomely during World War II with orders for over sixteen million units of clothing that were manufactured in over twenty plants across the country. In 1943, Reliance built a second Hattiesburg factory, known as the “Freedom Plant,” to help meet demand.31

Buoyed by wartime growth and a strong postwar domestic economy, production at Reliance expanded throughout the late 1940s. The Hattiesburg plants were so inundated with orders that they struggled to find enough employees. Reliance managers erected employment booths at local grocery stores and operated busses to transport workers from nearby towns. By the time Reliance celebrated its fifteenth anniversary in 1948, the company employed approximately eight hundred people and provided an annual payroll of over $1 million. For hundreds of young women, a position at Reliance was the first—perhaps the only—job they had ever held. One did not need any significant amount of training or skill to procure a desirable entry-level job at the factory. The only requirement was that one needed to be white.32

Hattiesburg’s second-largest employer during the postwar era was the Hercules Powder Company, the Delaware-based firm that first arrived in 1923. Hercules profited during the war by selling munitions to the Allies. The company continued growing after the war with the production of explosives and naval stores products such as turpentine, pine oil, and rosin. In 1950, Hercules invested approximately $1.5 million in the Hattiesburg plant to expand production of toxaphene, a highly toxic insecticide that was later banned in the United States. The dangerous products manufactured in Hattiesburg may have been hazardous to the environment and to public health, but they also provided over 650 local jobs through the 1960s.33

Unlike Reliance, Hercules employed large numbers of both white and black workers, all of whom belonged to the AFL-CIO affiliate Hattiesburg Chemical Workers Local No. 385. Although white and black employees belonged to a single union, this type of interracial labor organizing did not signify any significant threat to local segregation ordinances. In fact, the first incarnation of the union held racially separate meetings. The national AFL-CIO eventually convinced locals to abandon that practice, but black and white employees continued using separate entrances and restrooms, playing on segregated softball teams, and participating in separate social clubs. Interracial unionization and Jim Crow were not inherently incompatible.34

Nevertheless, the union did help facilitate a handful of examples of racial progress. Longtime African American Hercules employee Richard Boyd credits the union with his ability to become the “first black man to get and hold an operating position at Hercules,” a promotion he received in 1954, his fourteenth year with the company. Such cases, however, were rare. Most of the plant’s roughly two hundred-plus black employees held menial jobs and enjoyed far fewer opportunities for advancement than did their white counterparts.35

Jobs at Hercules were at once dangerous and desirable. White and black workers who had survived the Great Depression in America’s poorest state rushed to take positions handling dangerous chemicals because those positions offered stable work and decent wages. “That job at Hercules was supreme back in those days,” remembered Huck Dunagin, who worked at the plant between 1933 and the 1970s. Though the local union did not add much in terms of occupational safety, a nine-day strike in 1946 helped raise wages. By the late 1940s, wages at Hercules ranged from $0.67 to $1.38 per hour; employees who worked full-time at Hercules could thus earn between $1,580 and $2,870 per year. At the time, Mississippi’s average per capita income was $609. In the Southeast region, the average per capita income was $885; in the United States, it was $1,247. Even by national standards, Hercules workers were relatively well paid.36

The most exciting development in postwar Hattiesburg was the rapid expansion of Mississippi Southern College. Originally founded in 1910, the college changed its name from State Teachers College to Mississippi Southern College in 1940 to reflect the school’s transformation from a small teaching institute to a fully accredited college. Enrollment at the school declined briefly during World War II, but then it exploded during the 1940s and 1950s. From a low enrollment of roughly three hundred undergraduates in 1945, the student body expanded to approximately two thousand by 1950 and nearly five thousand by the end of the decade.37

Mississippi Southern’s growth was enabled by the GI Bill, the widely popular federal program that provided educational grants and low-interest loans to veterans. During the 1946–47 academic year, GI Bill–related expenditures accounted for an estimated $700 million of the roughly $1 billion the federal government spent on higher education. One historian of World War II veterans’ education has estimated that the program funded the higher education of approximately 450,000 veterans who otherwise would not have attended college. By 1947, veterans accounted for nearly 70 percent of all male college undergraduate students.38

The GI Bill fundamentally changed the student body at Mississippi Southern. Women had once comprised a large majority on the campus. During the 1935–36 academic year, for example, only 22 percent of students were men. Two decades later, men accounted for up to 63 percent of undergraduates. “Mississippi Southern College as it was known when I became president, had very few men students,” recalled school president R. C. Cook. “With the 1946–47 session, we began to get a large number of GI students.” Of course, this growth only included white male veterans. Most of Mississippi’s roughly eighty-five thousand black World War II veterans were also eligible for GI Bill benefits, but none of them were permitted to enroll at Mississippi Southern or any of the state’s other white institutions.39

The federally funded GI Bill provided enormous benefits to Mississippi Southern and a new generation of white students, enabling thousands of male students from working-class families to attend college. Their presence strained the campus’s residential and academic capacities, but also facilitated rapid growth of the school. Mississippi Southern responded to expanding enrollments by securing housing facilities from Camp Shelby and arranging for busses to transport students. The wave of new pupils justified curriculum expansion. Student demand led to new programs and departments, including a business school, departments of biology, speech and hearing, and physical education, and a graduate program in education. With such a rapid influx of students, the school successfully lobbied the state for additional funds that helped maintain constant growth throughout the 1950s. President Cook also expanded Greek life to include national sororities and fraternities, revamped the school’s marching band, and hired a full-time director to run the school’s athletic program, which joined the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1952. The increased enrollments remade the small teachers’ school into a large college with division-one sports. As President Cook later observed, “the influx of GI students changed the whole nature of the school.”40

In the postwar years, Mississippi Southern emerged as a central part of local life. The Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce was thrilled with the growth of the college. Rising enrollments brought thousands of educated residents to town, expanded retail opportunities, and created new jobs. The school also helped enhance a sense of community. Football games and homecoming parades were terrific for local boosterism and communal spirit, even among those who did not attend the college. Local white residents also benefitted from access to a large campus library and the beautiful on-campus park, Lake Byron, both of which had been financed by New Deal projects in the 1930s. As Mississippi Southern grew, the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce increasingly incorporated the college into its activities and programming. The organization even reserved a spot for President Cook and his successor on its board of directors.41

Although the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce was never able to fulfill its most ambitious industrial dreams, by the early 1950s, the city’s economy stood on solid ground. People who needed work could generally find it. Less than 25 percent of local adults held high school diplomas, but most people did not need an extensive education to earn a living wage in Hattiesburg. Thousands of men and women found blue-collar jobs at Reliance, Hercules, or in one of the city’s smaller manufacturing firms, service stations, restaurants, and retailers. In 1950, the city’s unemployment rate was 4.5 percent, and the median individual income was $1,578, roughly 50 percent higher than the state average. Local African Americans were blocked from many opportunities, but even their median individual income of $1,028 was the highest for a non-white population of any city in the state.42

The economic story of Hattiesburg in the postwar era was one not of explosive expansion but rather of slow and steady growth. Hattiesburg was not a bustling Southern metropolis in the model of Nashville or Dallas, but it was a place that offered opportunity for thousands of working-class people. So once again, people came. Between 1940 and 1950, the city grew from 21,026 residents to 29,474, an increase of over 40 percent. Most of these folks had lived through the depression and the war and were quite happy to find stability in postwar Hattiesburg. They worked hard, went to church, sent their kids to school, and continued to abide by the rules of a rigidly segregated society. Those who violated the rules faced severe consequences.43

Louis Faulkner was infuriated by the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision. Faulkner, a native Pennsylvanian and longtime Republican, was not a typical homegrown white Southern segregationist. But since arriving in Mississippi in 1905, he had become an ardent defender of Southern Jim Crow. As a longtime member of the Chamber of Commerce, deacon of Hattiesburg’s First Presbyterian Church, and leader in a variety of local organizations ranging from the Boy Scouts to the Rotary Club, Faulkner enjoyed a great deal of local influence. When federal policies threatened white supremacy, he sought to expand that influence far beyond local affairs.

Faulkner’s first major gripe was with the FEPC, the World War II–era executive order designed to prevent companies that practiced segregation from receiving defense contracts. When some members of the national Democratic Party began floating the idea of establishing a permanent FEPC after the war, Faulkner used his platform as a leader in the First Presbyterian Church to voice his opposition to any organization that supported the FEPC, including churches. Faulkner’s own company, Faulkner Concrete, and his employer, the Mississippi Central Railroad, had both received federal contracts during the New Deal and World War II; he had no real grievance over federal spending or influence when it benefitted him. The source of his agitation lay in the suggestion that white Southerners should be required to share the spoils of federal money with African Americans.

In 1947, Faulkner “urged withdrawal of the Southern Presbyterian church from the Federal Council of Churches of Christ (FCC),” reported the Hattiesburg American, because the FCC “had ‘committed more than 27,000,000 church members to FEPC legislation.’ ” In the following years, Faulkner constantly attacked the FCC (which in 1950 became the National Council of Churches [NCC]), delivering scores of speeches, writing hundreds of letters, and publishing numerous anti-NCC op-eds in the Hattiesburg American. Like many segregationists of his era, Faulkner positioned his critiques within the framework of the postwar Red Scare. Increasingly paranoid about the influence of non-Southerners, Faulkner in 1950 ceased all donations to national organizations based on growing suspicion of their support for civil rights or socialism.44

The Brown decision in May of 1954 intensified Faulkner’s activism. That July, Faulkner received a copy of an anti-Brown letter written by a Jacksonville businessman to an NAACP official. Faulkner was “so well impressed” by this letter that he mimeographed a thousand copies and “mailed them to the Governors, Attorney Generals and other officials of several southern states, and to a large number of ministers and other church officers.” This was the first of many efforts to distribute segregationist literature. Between 1954 and 1960, Faulkner essentially operated as a one-man clearinghouse for hundreds of segregationist pamphlets and essays. He had many allies.45

No state mounted a more venomous response to Brown than Mississippi. The state’s politicians seemingly scrambled to outdo one another with extraordinarily racist and cataclysmic rhetoric that went so far as to suggest the possibility of another civil war. “Negro education and interracial comity,” stated Congressman John Bell Williams, “suffered their most damaging setback since the War Between the States.” Congressman William Winstead argued that the decision would retard educational progress in the South “for at least half a century.” Mississippi senator James Eastland launched into a bitter, hour-long tirade on the Senate floor, accusing members of the United States Supreme Court of being “brainwashed” and promising “The South will retain segregation.”46

Louis Faulkner’s mailing campaign placed him in touch with a number of Mississippi’s leading segregationist voices, including Congressman Williams and Senator Eastland. In addition to distributing segregationist literature, Faulkner also worked to challenge the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s tax-exempt status as a nonprofit organization. Beginning in 1955, he wrote dozens of letters to high-ranking public officials, including administrators at the United States Treasury Department, the governor of Mississippi, White House chief of staff Sherman Adams, the commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, urging these officials to investigate the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and revoke the organization’s nonprofit status. None of these requests produced the desired results, but Faulkner was continuously encouraged by his fellow Mississippi segregationists. “You are certainly doing fine work,” Eastland wrote to Faulkner, “and the position which you take is the right one.”47

The motivations behind Faulkner’s crusade are curious. Apart from his angst over the school desegregation ruling, Faulkner in 1954 lived in relative ease and comfort. Having turned seventy-one that year, the longtime city leader was slowly retreating into retirement. He had given up his seat on the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce board of directors and was in the process of grooming his son-in-law to replace him as the head of Faulkner Concrete, which had rapidly expanded since securing federal contracts during the New Deal and World War II. He and his wife of over forty years lived in a beautiful, 6,000-square-foot home they had built in the 1920s. And his daughter and son-in-law lived just two blocks away with his grandchild. Life was seemingly good for Louis Faulkner. Nevertheless, he spent his final years on earth engaged in an obsessive fight against a school desegregation ruling that bore no practical consequences for his own life.48

With limited influence at the federal level, Mississippi segregationists employed several new strategies to fight desegregation. Their first tactic, which actually predated the Brown decision, was to provide more funding for black public schools in a preemptive attempt to ward off a broad federal mandate. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mississippi officials built new black public schools (with construction of a new black high school in Hattiesburg beginning in 1949) and raised black teacher salaries in an attempt to show that segregated schools could be equal. Between 1946 and 1953, the state spent an unprecedented $11 million on black public schools.49

Yet broad racial disparities remained. Despite increased funding for black schools, Mississippi never came even remotely close to equalizing segregated schools. Even if state legislators insisted that funds be proportionately distributed between black and white schools, local white superintendents and school boards still allocated far more resources toward white schools. The $11 million spent on black schools between 1946 and 1953 paled in comparison to the $30 million spent on white schools during that same period.50

This half-hearted school equalization program continued after the Brown decision. In another case known as Brown II, the United States Supreme Court in May of 1955 ordered school districts to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” language that was designed to alleviate potential social upheavals if states were forced to instantaneously restructure their public school systems. Brown II gave some segregationists hope that they might be able to continue avoiding school desegregation by equalizing school funding. But disproportionate public school funding continued. As late as 1962, Mississippi’s average per-pupil expenditure was still nearly four times higher for white students than for black ones.51

The second tactic to combat desegregation was the creation of a statewide investigative unit named the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, which surveilled any group or individual advocating civil rights or desegregation. “The duty of the commission,” read the enacting legislation, was “to protect the sovereignty of the State of Mississippi, and her sister states, from encroachment thereon by the Federal Government.” To conduct its mission, the state-funded Sovereignty Commission employed full-time investigators, worked with local law enforcement officials, and even hired African American informants. The organization was particularly concerned with the NAACP because of its central role in the Brown decision. Anyone with suspected NAACP ties was subject to intensive investigation and potential retribution.52

The third and most proactive approach toward resisting desegregation was led by the Citizens’ Council, a grassroots organization. Founded on July 11, 1954, the Mississippi Citizens’ Council was organized by a man named Robert Patterson as a vehicle for white segregationists to “stand together,” in Patterson’s words, “forever firm against communism and mongrelization.” The Citizens’ Council was led by middle- and upper-class white professionals who primarily used economic pressure to restrict civil rights activism. As one of its founding members explained, “It is the thought of our group that the solution to this problem may become easier if various agitators and the like be removed from the communities in which they now operate. We propose to accomplish this through the careful application of economic pressures.” The council, which exchanged intelligence and received financial support from the Sovereignty Commission, hounded suspected civil rights activists through financial penalties. Among other activities, the organization instructed banks to deny loans, employers to terminate employees, and wholesalers to cut off supplies to anyone accused of advocating civil rights. The Citizens’ Council touched virtually every corner of the state. Sixty thousand Mississippians joined in the first year alone. Within two years, the organization counted over eighty thousand dues-paying members in Mississippi and had spread to all parts of the South.53

The Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council was founded at the downtown courthouse on the night of March 22, 1956. The inaugural meeting was announced in a front-page story in the Hattiesburg American. One hundred people attended the first meeting, a turnout that disappointed attorney Dudley Conner, who concluded that with dues as low as $5, the local Citizens’ Council “should have at least 5,000 members.” Another early member, businessman M. W. Hamilton, explained the essence of the organization’s racially based motivations. “The black race,” Hamilton later told an interviewer, “in our opinion hadn’t advanced to the point where they could contribute anything to the schools.” “The white race,” he claimed, “is probably ten thousand years ahead of them in intelligence.”54

The Citizens’ Council promoted its message publicly but operated subversively. Although the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council left behind no public membership rolls, newspaper accounts reveal the names of some members: attorney Dudley Conner was the first president; another attorney, Thomas Davis, served as vice president; real estate agent Dennis Frost was the treasurer; and postal clerk David Reed was the secretary. Luther Cox, the longtime Forrest County circuit clerk infamous for asking black voter registrants about bubbles in a bar of soap, was also among the original members. The composition of other Citizens’ Councils suggests that most members were middle- to upper-class white citizens, the same demographic that would have belonged to the Kiwanis, the Rotary Club, or the Chamber of Commerce. Unlike those other civic organizations, however, the Citizens’ Council operated almost entirely in secret.55

Louis Faulkner’s name does not appear on any Citizens’ Council rosters, but an abundance of evidence suggests he was a member. Faulkner not only helped distribute Citizens’ Council literature, he also regularly corresponded with high-ranking Mississippi Citizens’ Council officials, including the organization’s founder, Robert Patterson, and its most notorious member, Judge Tom P. Brady, whose 1954 segregationist pamphlet “Black Monday” is widely credited with inspiring the creation of the Citizens’ Council. Later in life, Brady was labeled by Time magazine as “the philosopher of Mississippi’s racist white Citizens’ Councils” and recognized by the New York Times as the “intellectual godfather of the segregationist Citizens Council movement.” Brady and Faulkner often exchanged letters and appear to have been fairly close acquaintances. In fact, they had known each other for decades; during the 1920s, Brady’s father worked for Faulkner as legal counsel of the Mississippi Central Railroad.56

As the Citizens’ Council spread, Mississippi became increasingly deadly for civil rights activists. In May of 1955, voting rights activist Reverend George Lee was killed in a drive-by shooting in Belzoni, Mississippi. In August of the same year, voting rights advocate Lamar Smith was shot and killed in Brookhaven, Tom P. Brady’s hometown. That November, one of George Lee’s allies, Gus Courts, was also shot and almost killed in Belzoni. Other African Americans murdered that year include Emmett Till, Timothy Hudson, and Clinton Melton. The final three were not killed explicitly in retaliation for civil rights activities, but it is impossible to ignore the context. Rumors of a “death list” floated among the state’s NAACP leaders. Any black civil rights activist operated under a pall of fear.57

The Citizens’ Council always denied involvement in violence, but at the very least, the organization helped identify and publicize targets. When Louis Faulkner came across copies of a Jackson-based pro–civil rights newspaper named the Eagle Eye, for example, he took it upon himself to distribute copies to white segregationists across the state. Arrington High, the Eagle Eye’s publisher, was later arrested and committed to the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, where he lived for five months before being smuggled out of the state in a casket. Most cases of retribution cannot and should not be accredited to any single Citizens’ Council member, but the organization’s affiliates clearly played a vital and active role in spreading information about civil rights activists. Members of one branch claimed that “the Council is not an anti-negro organization, but that it is opposed to radical outside elements who are attempting to break down the Southern way of life.” Virtually all of their activities, however, were designed to hurt native black Mississippians.58

Repercussions in Hattiesburg were generally less severe. Locally, the broadest consequence was probably a decline in membership of the Hattiesburg NAACP from 110 in 1955 to 25 in 1956, then 20 in 1957. Deterrents were obvious. People were concerned about job loss, informal economic sanctions, and violence. The threat of violence was nothing new to black Southerners, but the long reach of the Sovereignty Commission and the Citizens’ Council elevated the risk of racially subversive activities.59

Those who remained in the Hattiesburg NAACP tended to be either entrepreneurs or ministers, who were less susceptible to economic repercussions. Milton Barnes, owner of Barnes Cleaners and the Embassy Club, led the organization for much of the late 1950s. Other entrepreneurial members included Hammond and Charles Smith, Vernon Dahmer, grocer Benjamin Bourn, newsstand owner Lillie McLaurin, grocer Annie B. Howze, and several local black teachers. This small group also included the pastor of each of the four largest churches in the Mobile Street District—George Williams of St. Paul Methodist, James Chandler of Mt. Carmel Baptist, W. D. Ridgeway of True Light Baptist, and W. H. Hall of Zion Chapel A.M.E.60

The involvement of ministers offers interesting implications for local NAACP activities. Although the organization counted only twenty official members in 1958, it was supported by at least several hundred local residents. One did not necessarily need to formally belong to the NAACP to support its cause. In 1958, several disgruntled members of Mt. Carmel Baptist told a Sovereignty Commission investigator that Reverend James Chandler had been passing around a collection plate in support of the NAACP. When these particular members objected, Chandler “had them thrown out of the church,” read the Sovereignty Commission report. Chandler also organized an ad hoc budget committee that in some unknown way managed the funds raised in support of the NAACP. This type of activity suggests that the NAACP was supported by potentially hundreds of members at Mt. Carmel, which rebuilt in 1953 to accommodate eight hundred people. It is not known if Chandler’s contemporaries at St. Paul Methodist, True Light Baptist, and Zion Chapel A.M.E employed similar fundraising tactics. If they did, then the actual number of NAACP supporters in the Mobile Street District could have numbered in the thousands.61

Financial independence helped insulate clergy and entrepreneurs but did not leave them completely immune to retribution. In 1957, Reverend W. D. Ridgeway of True Light Baptist Church traveled to Washington, DC, where he testified in front of a Senate subcommittee about voting rights. According to Mississippi NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers, when Ridgeway returned to Hattiesburg, a man arrived at his home to inform him that his car was being repossessed. Soon thereafter, Ridgeway’s son-in-law was suddenly denied a previously arranged loan to purchase a home. That same year, local NAACP leader Milton Barnes lost the license to sell beer in his club. The following year, the club burned down in an unsolved fire. There is no evidence directly connecting the Citizens’ Council to either event, but let each reader consider the delicate balance between context and coincidence.62

Although most activities of the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council remain unknown, there were at least two definitive victims—one white, one black—whose lives were ruined in retaliation for challenging racial segregation. The first was a white man named P. D. East. Born in 1921, East grew up in the Piney Woods near Hattiesburg. After briefly serving in the military during World War II, he took a job as a railroad ticket agent before being hired to manage the newsletter produced by the union at the Hercules Powder Company. In 1953, he started his own newspaper, called the Petal Paper, in Petal, a small township in the northeast part of Hattiesburg.63

At first, the Petal Paper was fairly popular among locals. Desiring to “keep everyone happy,” East focused on local events and profiles of community leaders. He wrote about the local football team and church events, and included a “Citizen of the Week” in every issue. His theory for running a successful local paper was simply to “mention everyone’s name.” “Had Joseph Pulitzer established a prize for ‘Pleasing Everyone,’ ” East recalled, “I feel certain I’d have won it twice in the same year.” In its first year, the Petal Paper had nearly two thousand subscribers and almost forty advertisers. But then East began discussing school desegregation.64

East was not drawn into the school desegregation issue by the Brown decision but rather by a statewide referendum in December of 1954 to close Mississippi’s public schools. The referendum, which passed by a majority of two to one, would have allowed the state legislature to “abolish public schools” and use the saved expenditures to subsidize tuition for white students to attend private schools. East, who never publicly endorsed Brown, labeled the amendment “a black mark against the state,” editorializing that “whenever we are forced to pay taxes for private education we are just that much closer to a dictatorship.” East’s editorials generated immediate backlash. One store owner who advertised in the Petal Paper told East, “Well, I sure won’t advertise in any paper that’s against the school amendment. Anybody who wants niggers to go to school with my children, I won’t do business with.” Soon after East printed his editorial, the man and several other advertisers pulled their support.65

East lost additional supporters with a string of editorials that increasingly drew the ire of local white residents. Some people were unhappy when he labeled Abraham Lincoln’s death “unfortunate.” Others cancelled subscriptions or pulled advertisements after East criticized the acquittal of the two men who killed fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in another part of the state. East also received angry letters from disgruntled readers after he suggested that heaven was not racially segregated. And he received even more flak for making the simple observation that only eight of Forrest Country’s twelve thousand African American citizens were registered to vote. “In the state of Mississippi,” East wrote, “a Negro asking to register to vote is about like asking Satan for a drink of water.”66

East’s greatest offense occurred in March of 1956 when he published a parodic advertisement known as the “Jack-Ass Ad” that mocked the formation of the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council. In a searing editorial, he referred to the group as the “Citizens Clan” and warned locals against the travails of “fear,” “ignorance,” and “mass insanity.” Subsequent editorials further mocked the organization, calling it the “Ku Klux Council” and the “Bigger and Better Bigots Bureau,” while charging the council with responsibility for a slew of violent public incidents directed against local African Americans. When a seventeen-year-old boy was randomly beaten unconscious by a group of white youths in May of 1956, East editorialized, “We do not believe that Council members were in any way involved, but we believe that with the organization of such an outfit, certain unintelligent, bigoted, inferior whites feel something resembling guardian-angel protection of their existence.”67

Retribution came swiftly. By autumn of 1956, East had lost every single one of his local advertisers and his circulation had fallen from a high of nearly two thousand to just nine. The Citizens’ Council, he later learned, had warned local merchants against advertising in his paper. During this time, he also experienced constant harassment and social ostracism. People whom he had known since childhood stopped speaking to him in public and inviting him to social functions. Strangers delivered threats via phone, mail, and daily interpersonal interactions. His wife was followed. He bought a gun for self-defense. He developed an ulcer and a drinking problem. With the loss of advertisers and subscribers, he fell deeply into debt. His wife left him. The Citizens’ Council kept a large file on him and reported his activities to the Sovereignty Commission. “We have a full file on East’s activities,” reported a Citizens’ Council official to the Sovereignty Commission. Rumors spread of a price on his head. “They’re going to kill you,” warned a member of his family. East eventually fled the state.68

The second victim of the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council was a black man named Clyde Kennard. Born on June 12, 1927 (he was delivered by Dr. Charles Smith), Kennard grew up on his grandmother’s farm in Eatonville, a small rural settlement located just north of Hattiesburg. He spent much of his youth working on the farm and attending the tiny local black school. In 1945, he left Hattiesburg to join the United States Army. While enlisted, Kennard served in Korea, obtained his GED, and took courses at the all-black Fayetteville State Teachers College while stationed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. After his honorable discharge in 1952, Kennard enrolled at the University of Chicago.69

In 1955, Kennard returned to Mississippi to help his mother run the family farm. Desiring to continue his education, Kennard applied for admission to Mississippi Southern College. A self-described “segregationist by nature,” Kennard might have applied to a black college if one had been located closer to his home. But the nearest black college was located more than an hour away in Jackson. When Kennard called Mississippi Southern to ask for an application, he “stated that he was a negro,” reported the registrar, and thus never received the form. Kennard then visited the campus, where he met with the school’s new president, William D. McCain, who informed Kennard that applicants to Mississippi Southern needed to secure “five recommendations from former alumni in Forrest County,” which was, of course, a virtually impossible task for any African American applicant at that time. Kennard submitted his application anyway, but was rejected on the grounds that he had submitted an incomplete file. Kennard dropped the issue and spent most of the next three years helping run his family farm.70

Mississippi Southern president William McCain was a white supremacist neo-Confederate who idolized Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan pioneer Nathaniel Bedford Forrest. He hung a portrait of Forrest in his office and changed the school’s mascot from the Yellow Jackets to “General Nat.” “Hopefully,” McCain once wrote, “General Nathan Bedford Forrest whose courage and valor gave this County its name will continue to inspire victory over adverse circumstances and good citizenship.” Committed to preserving segregation, McCain joined the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council and worked with the segregationist organization when Kennard once again decided to apply for admission to Mississippi Southern.71

Between 1955 and 1958, Clyde Kennard helped run his mother’s farm and worked as a general laborer for a downtown department store. He also became increasingly involved in the local NAACP. Vernon Dahmer, who lived near Kennard in Eatonville, helped introduce the former serviceman to the organization. Kennard attended local NAACP meetings and served as advisor for an NAACP Youth Council in nearby Palmer’s Crossing. After he was denied the opportunity to register to vote in 1957, Kennard was one of several local African Americans who completed affidavits for Mississippi NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers. In 1958, he decided to reapply to Mississippi Southern College.72

That November, Kennard telephoned Mississippi Southern registrar Aubrey Lucas to request five applications for himself and four other African Americans for the upcoming winter semester. Lucas, whose black maid was acquainted with Kennard and reported him to be “well educated” and “very intelligent,” told the black applicant he could only send him one application. If there were indeed four other interested prospective black students, none of the rest called to ask for an application. Kennard acted alone. He did not even ask the NAACP for help, but the organization and several national black media outlets did closely follow his case.73

In response to Kennard’s 1958 application, the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council worked with the Sovereignty Commission to launch a major investigation into Clyde Kennard. Sovereignty Commission investigators examined his public and Army records, interviewed dozens of acquaintances, checked his credit report, examined property transactions, searched for any potential FBI records, and even hired a former FBI agent to investigate Kennard’s activities in Chicago. The goal of this extensive investigation was to uncover some past transgression that might serve as grounds to reject Kennard’s application. Regardless of his credentials, Mississippi Southern College officials had no intention of ever voluntarily admitting Kennard. But they and other segregationist leaders were concerned about having to wage a legal battle against the national NAACP. Despite searching far and wide for some major character flaw, the Sovereignty Commission found no damning evidence in Kennard’s past. Even the white people they interviewed uniformly endorsed his character and intelligence.74

Dudley Conner, the head of Hattiesburg’s Citizens’ Council, suggested that Kennard could be killed. According to a Sovereignty Commission investigator, “Mr. Connor [sic] stated that Kennard’s car could be hit by a train or he could have some accident on the highway and nobody would ever know the difference.” Conner was not alone. That December, the head of security at Mississippi Southern was approached by a group of unnamed individuals who suggested planting dynamite in the starter of Kennard’s vehicle.75

The Sovereignty Commission decided not to follow these suggestions. Instead, it recruited a group of influential black Hattiesburgers—principals N. R. Burger, Clarence Roy, and Alfred Todd and local pastor Reverend Ralph Woullard (a Sovereignty Commission informant)—to meet with Kennard to convince the prospective student to withdraw his application. One interesting item of note is that each of the black principals “brought into the conversation their need for a Negro Junior College in that area.” “The inference was inescapable,” noted the Sovereignty Commission investigator, “that they were attempting to bargain in a subtle manner.” In any case, this meeting achieved its intended result. Kennard withdrew his application. But he was not yet finished.76

The following autumn, Clyde Kennard once again applied to Mississippi Southern. Unable to procure the required five letters of recommendation from local alumni, Kennard instead submitted five letters from “professional people who live in my community, and have at least the equivalent of a degree from Mississippi Southern College.” “As a Negro,” Kennard argued in his application cover letter, “I feel that these people would be in a much better position to attest to my moral character.” After receiving a call from President McCain, the Sovereignty Commission opened another investigation and explored the possibility of once again recruiting the ad hoc “negro committee” to speak with Kennard. This time, however, local actors took more initiative. Because their actions were planned in secret, there is no record of which individuals were responsible for each action. What follows is a description of the basic facts.77

Less than two weeks after McCain learned of Kennard’s intention to reapply, the office manager of the Forrest County Cooperative, where Kennard conducted business, filed a $4,300 claim against Kennard based on an unsubstantiated breach of contract. After Kennard refused to transfer a deed of trust to the co-op, representatives from the co-op seized and sold all the hens on Kennard’s farm. Soon thereafter, the Southern Farm Bureau Insurance Company cancelled the insurance policy on Kennard’s automobile.78

McCain invited Kennard to meet with him in his office on the morning of September 15, 1959. At the meeting, Kennard steadfastly refused McCain’s requests to withdraw his application. After a twelve-minute meeting, Kennard was “ushered out of a side door,” reported the Sovereignty Commission, to avoid members of the media who had gathered outside McCain’s office. When Kennard arrived at his automobile, he encountered two local policemen who claimed to have seen the vehicle speeding earlier that morning. The policemen arrested Kennard on the charges of reckless driving. Once at the jail, the thirty-two-year-old veteran learned that he was also being falsely charged with illegal possession of whiskey. Clyde Kennard did not drink.79

Upon making bail, Kennard drove to Jackson, where he conferred with NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers, who helped arrange legal counsel for Kennard’s defense. The trial was a sham. Kennard was convicted of all charges and lost subsequent appeals. The convictions provided the grounds for Mississippi Southern to reject any further applications from Kennard based on moral depravity. And yet he persisted. Over the following months, Kennard published two letters in the Hattiesburg American outlining the reasons why he should be admitted to Mississippi Southern. “The question,” he stressed in one letter, “is whether or not citizens of the same country, the same state, the same city, shall have equal opportunities to earn their living, to select the people who shall govern them, and raise and educate their children in a free democratic manner.” During these months, he also continued his work with the local and statewide NAACP.80

On Sunday, September 25, 1960, Clyde Kennard was rearrested on false charges that he helped orchestrate the theft of $25 worth of chicken feed from the Forrest County Cooperative. A nineteen-year-old black man named Johnny Lee Roberts, whose car was spotted leaving the scene of the crime, identified Kennard as a co-conspirator. Roberts later recanted this testimony on numerous occasions, most openly in 2005 when he told a reporter that Kennard “wasn’t guilty of nothing.” Nonetheless, the accuser’s testimony in 1960 provided adequate evidence for a jury to deliberate for just ten minutes before finding Kennard guilty of burglary. Roberts, who actually committed and admitted to the burglary, received a suspended sentence. Kennard was sentenced to seven years in prison. NAACP-led efforts to overturn his conviction at the state level were unsuccessful, and a federal judge sent the case back to the Mississippi Supreme Court.81

While in prison, Kennard contracted stomach cancer. In June of 1962, a physician gave Kennard a mere 20 percent chance of living longer than five years and recommended immediate parole for the sake of survival. Despite pressure from the NAACP and other advocacy groups, officials at the Parchman State Penitentiary not only refused parole but continued forcing Kennard to perform hard labor in the fields surrounding the prison. Dying of stomach cancer, Kennard was forced to work for at least six months after his diagnosis. Whenever he collapsed of exhaustion, other inmates dragged him back to his bed. Clyde Kennard was finally released in January of 1963. On July 4, 1963, he died of stomach cancer at the age of thirty-six.82

Clyde Kennard and Mississippi Southern president William McCain stand as remarkable contrasts to the accessibility of opportunity for black and white residents of Hattiesburg in the postwar era. Whereas Kennard was a humble, hard-working veteran of the Korean War who spent much of his time in service to others, McCain was an arrogant plagiarist who was later discredited by the American Historical Association for submitting portions of a student’s master’s thesis as his own work. Yet McCain was white, and Kennard was black; one enjoyed full access to the finest opportunities available in the postwar era, while the other was imprisoned for merely suggesting that he too deserved an opportunity. In arguing his case for admission to Mississippi Southern in 1958, Clyde Kennard wrote, “What we request is only that in all things competitive, merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race.” But such a stance contradicted the essence of Jim Crow. Race trumped merit, and individual dignity provided no additional safety. The consequences for people like Clyde Kennard were devastating and tragically unfair.83

Louis Faulkner passed away of a chronic heart condition on January 16, 1961, at the age of seventy-seven. For over fifty years, he and his colleagues in the Chamber of Commerce and other organizations had tried to increase their access to resources provided by Northerners and the federal government while mitigating the effects of outside influence on the local racial hierarchy. When outside forces appeared to threaten the foundations of white supremacy, they howled about federal overreach and “states’ rights,” while trying to suppress local attempts at black advancement. Paradoxically, they also appealed to federal officials for help in maintaining their society’s racial order. In 1955 and 1956, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover felt compelled to explain in letters to Louis Faulkner that it was “not within the province” of the FBI to make judgments over the tax status of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.84

The hysteria of white segregationists over the FEPC and the Brown decision created a powerful and dangerous backlash, but their fight to maintain Jim Crow still contained one fundamental flaw: the continued denial of black voting rights. Black disfranchisement was central to Jim Crow because it undercut African Americans’ ability to influence social policies and resource allocation by voting. But such systematic and blatant disfranchisement always left open the possibility that federal legislators might take seriously the continuous violations of the Fifteenth Amendment. The burden to prove those violations, however, lay with black Southerners. In 1950, black Hattiesburgers had first attempted to prove these constitutional violations with the case Peay et al. v. Cox. The early 1960s presented another opportunity. Just months before Louis Faulkner died, FBI agents arrived at the Forrest County Courthouse to check “on voting,” noted a Sovereignty Commission report, “and voting registration of negroes.”85