Chapter Seventeen

John Fante Writes Again

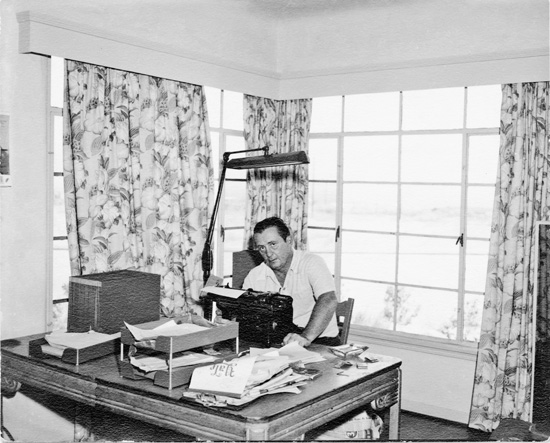

By the mid-1960s, Pop hadn’t published a book in thirteen years. He did well-paid, imaginative, grunt-work screenwriting but was washed up as a novelist and had become furious with himself. John Fante felt he was a failure at what he most loved—writing books.

In 1964, John Fante, after another break from writing fiction, was sending off half the manuscript of his proposed novel later entitled 1933 Was a Bad Year. The rejection letters he got back were all similar in their harshness toward this new work: You’ve lost your touch, Fante. Stop writing about your past and your family.

Pop became seriously depressed and began drinking again—diabetes or no diabetes. Several nights a week he could be found at the Malibu Cottage. One night, after several hours on a stool, in a heated conversation over the L.A. Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants, he was invited “outside.” Before Pop’s combatant could get his jacket off and his hands up, he was caught with a succession of hooks and crosses that left him bloody on the parking lot blacktop. No one, but no one, insulted the Dodgers—especially after Pop’d had five drinks.

Over time Billy Asher, one of our Malibu neighbors and a poker-playing buddy, had become friends with my dad. Billy had directed I Love Lucy and was a big success by television standards. But Asher had an Achilles’ heel that my old man discovered almost immediately: With all his accolades on the small screen, he had never made a successful transition from television to movies. It was his weakness. A sore spot.

In discussions with Asher, my father had come up with an idea for a TV series called Papa. It would feature a cigar-smoking, aging Italian male parent of six kids, their troubles, and his homespun, old-world solutions.

Asher loved the idea and used his clout in the TV industry. Hopes were high. He took the pilot script with him to New York and wound up making several trips to present it to the various networks’ brain trusts. While reception to the idea was warm, there were no firm takers. Time went by and nothing happened. The idea was finally dropped.

A year or so later, my father had just finished a spec script and bumped into Billy in Malibu. By now Asher had gotten divorced and moved away but was on holiday at the beach, visiting. Pop told him he had just finished a script that he was sure would make a great film. Billy suggested that my dad send it to him and that maybe he could help in placing it with the right production company.

John Fante greatly disliked having to be solicitous, asking for anything from anyone. Six weeks later, when he had not heard back from Asher, he made the phone call. When Asher came on the phone, they chatted for a few minutes and then Pop asked his TV giant pal what he thought of the film script. “Great, Johnny. I loved it. No kidding, but it’s a bit too character driven with not much action. It’s the kind of film idea that’s not hot right now.”

There was a long pause on my father’s end of the line, then the snarling words, “You mean because it’s not a fucking sitcom! I forgot you’re a limp dick—a guy who’s been a no-show in the movie business for the last twenty years.”

The two men did not speak again for years.

In the late 1960s, another novel was in the works, My Dog Stupid. John Fante had been forced through lack of screen work to return to what he truly loved. The book would posthumously be judged by many critics as one of his best. It was set in the present and involved an aging screenwriter needing to find something worthwhile in his life and marriage. There was sadness and irony and humor and great wisdom in its flawed main character, a man floundering to rediscover himself. Pop’s character Henry looks out from the window of success and security to examine a life of easy choices and mistakes. It was brilliant stuff written with my father’s characteristic simplicity and insight. Sadly, one more time, another fine piece of fiction was completed that would not see print until after my father was dead.

My father was an artist, win, lose, or draw. He avoided his passion for long periods but never denied it. Throughout a life of near obscurity, he clung to his gift. Most of his novels were written for nothing. Not fame. Not recognition. He wrote because a writer was what he was. For me, his second son, a ne’er-do-well, a whackjob, and an alcoholic, this enduring example made me love him with all my heart.

Back in New York my life began to crash. My relationship with Mo was winding down. I had become a version of my father: snarling, angry, and uncommunicative. For months I’d made a habit of spending as much time away from home as possible and our sex had stopped long before. Talking without hysterics had stopped too. I’d come from a family with a hundred secrets that no one ever spoke about. The outside looked fine—the inside was a snake pit. I’d been raised by smart, verbal people who never discussed their own madness or differences except to assign blame. My relationsip with Mo was a photocopy of that.

I had been changing jobs regularly: night guard, waiter, proofreader, and hardware-store stock clerk. I quit them all or got fired. Drinking and porn had been the only things that had ever helped to stop my brain and its endless accusations. Now they were gone. Unmedicated, on a natch, I had an unfiltered streaming internal monologue keeping me awake every night. Sometimes it’d be louder than others. Sometimes it would scream: You dumb fuck, why did you talk to your manager like that? You don’t know what you’re doing. They’ll fire your ass for sure. You’re a mental cripple.

I spent a month studying for the taxi exam and with Mo’s coaching passed it, having never driven a car in New York City and not knowing Wall Street from Fifth Avenue. My hack license was issued, #7912.

A few weeks after I started the taxi job, Mo and I finally split up. The relationship had essentially been over for months.

I moved my clothes to a residential hotel on Fifty-first Street in Manhattan, and began drinking again in earnest.

With the end of the relationship came another physical reaction: I stopped eating. I knew I needed food, but the best I could do was a quart of Pepsi and a bag of Fritos a day. This went on for three months.

I knew I was crazy. Two or three times a week I’d find myself drunk at porno movies on Forty-second Street. During the day, while driving, I’d become overwhelmed by a feeling from nowhere and have to pull my cab over to the curb because I would be sobbing and out of control.

Because sleep was impossible, I began walking again at night to exhaust myself. Forty or fifty blocks. The East River to the Hudson River and back again. Sometimes I would stop to get a blow job from whatever Times Square guy was handy, then return to my hotel and drink myself to the point where I could pass out.

A darkness had come to my life, a despair that only those who have known the unendingness and bottomlessness of their own psyche can understand. No matter what I did or what female hostage I took in a relationship, I knew that sooner or later I would die from suicide. And, as it turned out, I would continue to drink for at least another fifteen years.