I HAD ALWAYS WANTED TO WORK ON A BOOK with Marilyn Monroe, from the first time I met her on a freelance photographic assignment back in September 1954. At that time she was in New York City on location for The Seven Year Itch. I initially conceived of the book as an ongoing series of my photographs of her as she went through her daily activities over the next several years, accompanied by her words as I interviewed her. Unfortunately such a book was never to be, but I think the one you are reading now gives new life to Marilyn.

Earlier in 1954, I had suggested to one of my editors, the late Donald Feitel of the Metro Group, that I produce a picture-text story. Since Marilyn had become so popular, her fans and the public couldn’t read enough about her, especially about the candid, off-guard moments in her life. Feitel agreed and suggested I take as many pictures of her as I could manage.

When I first caught sight of Marilyn, she was leaning out the window of a brownstone on fashionable 61st Street on the East Side of Manhattan, posing for a film scene. Actually my first glimpse was of her behind. When I took some photos of that now-famous backside, the sound of the camera’s shutter surprised her. She quickly turned around, spotted me, and smiled. I took a dozen more pictures, we both laughed, and the ice was completely broken. She certainly had a sense of humor. I subsequently followed Marilyn around for days, interviewing her and taking photos. She was great to work with.

What I particularly liked about Marilyn was that she didn’t act like a movie star. She was down to earth. Although she was then twenty-eight, she looked and acted like a teenager. Sure, she was beautiful and sexy, but there was an almost childlike innocence about her. I was most impressed that Marilyn was always polite and friendly to everyone on the set. She was no phony or snob.

Amazing as it seems, in the few days I worked with her we became friends. We discovered that we’d been born under the same sign: Gemini. Marilyn’s birthday was June 1; mine June 14. We liked the same things, and she was easy to talk to. I told her I’d like to work with her on a book about her life. She thought about it for a while; then her eyes opened wide, she smiled and answered, “Why not? Let’s do it someday.”

But it wasn’t until 1962 that we finally got around to seriously thinking about putting our book together. She had been busy making film after film and had become the international star I knew she was meant to be. I was busy traveling the world doing my stories. And though we had not seen each other, we had kept in touch—thanks to the telephone.

In May 1962 I was on assignment for Cosmopolitan magazine for a cover story on Elizabeth Taylor, who was then filming Cleopatra in Rome. Elizabeth was the first actress to receive a million dollars, plus expenses, for appearing in a film. The film shoot had begun in England, where Liz became ill and nearly died. Twentieth Century-Fox, the same studio that then employed Marilyn, had moved the production to Rome, where the warm climate better suited Elizabeth. There she could recuperate from a recent operation and resume filming. Not only was the star sick, but the entire production was in serious trouble. The studio was going bankrupt because of the film’s enormous expenses. There was no completed script; writers were writing scenes the same day they were filmed. Richard Burton was having an affair with Taylor while she was married to singer Eddie Fisher. Fisher had no idea how to put a stop to his wife’s affair. What a fiasco—I couldn’t wait to get back to New York.

Once back in the City, I had lunch with Bob Atherton, the editor of Cosmopolitan. As a photojournalist my livelihood usually depended on suggesting salable magazine stories to the editors I freelanced for. My friend Marilyn Monroe was making news. She was starting her thirtieth film, which would be her last for Twentieth Century-Fox under her old contract. It was time I did a major story on her. The idea I presented to the Cosmopolitan editor: What was Marilyn’s future now that she was turning thirty-six? The title of the film she was working on, Something’s Got to Give, could well apply to her career. Could she at thirty-six continue to play sexy, beautiful young women?

Atherton loved the idea. We agreed that it would make a cover and eight to ten pages in the magazine. The idea so excited us both that we didn’t even finish our lunch. He asked me how soon I could leave for Hollywood, where the film was already in production at the Fox studios. I told him I could leave immediately.

When I got to Hollywood, I checked into the Sunset Tower apartments on the Sunset Strip. After a good night’s sleep, a studio limousine took me the next morning to the Fox studio and Stage 14, where Marilyn was filming. Would she be glad to see me? Would she even remember me by sight? Many big stars meet so many people they have trouble remembering who they were introduced to the previous day—and we hadn’t seen each other for a few years.

When I entered Stage 14, I spotted Marilyn right away and walked over. Her back was to me, so I tapped her on the shoulder. “Hi. Remember me?”

She turned around, smiled, and, with a big hug, said, “It’s been a long time. What’s the occasion?”

“Well,” I replied, “since today is June first, I thought I’d fly out from New York to see my ol’ friend—note I said ol’, not old.”

She laughed as I hugged her again and said, “Happy-happy, and may you have only happy ones.” I told her about the Cosmo story; she loved it.

“Maybe, Marilyn,” I suggested, “it’s time we did the book we talked about all these years.”

She laughed. “Maybe the time is right now. Why not?” George Cukor called for her to appear on the set. Marilyn asked me to stick around—we could talk about the book, and other things, later.

Marilyn seemed excited about the film. Her leading man was Dean Martin, whom she had always wanted to work with, and she had gotten good parts for two of her friends. Both were comedians—Phil Silvers, the TV star of the old Sergeant Bilko show, and Wally Cox, who had played Mr. Peepers on TV years before. Also in the film was her friend Cyd Charisse, the dancer and wife of actor-singer Tony Martin.

At five thirty that Friday afternoon, Marilyn had finished her scene. It was time for her to call it a day. Then someone shouted “Happy birthday, Marilyn!” One of the crew wheeled out a huge birthday cake. It had white frosting with a sexy sketch of Marilyn in a bikini and HAPPY BIRTHDAY MARILYN written in huge letters—topped with July Fourth sparklers shooting tiny stars. And of course there was Marilyn’s champagne, Dom Perignon.

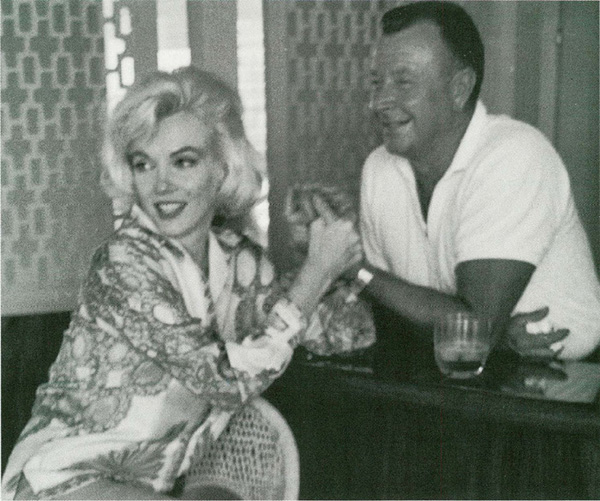

The Fox film crew and cast had remembered Marilyn on her birthday, and this brought tears of joy to the excited actress. She motioned to me to come over and help her cut the enormous cake. The photographers took pictures of us together while everyone was singing “Happy birthday, dear Marilyn / We all love you, and may all your wishes come true.” I had never seen a happier Marilyn.

By six thirty, Marilyn had passed out slices of the cake and glasses of champagne to everyone. She waved a goodbye, turned to me, and said, “Let’s get together Monday morning early on the set, around eight.”

Monday, June 4, arrived, and I was on the set early—but there was no Marilyn. In fact, Marilyn did not show up for work all week. She sent word that she was sick at home with a virus, a high temperature, sore throat, and stomach pains.

With Marilyn out sick all week, the Fox executives began to panic. They had depended on Marilyn’s movie to rescue the studio from its impending bankruptcy. They did not want to believe that she was sick. They even sent the studio doctor to check her out, and when he reported back on her illness, they still refused to believe she was too sick to work.

The publicity department released stories to the press (under studio executives’ orders) that Marilyn was out to ruin Fox. They implied that she did not care about the huge staff of workers on the film who were now unemployed because she refused to show up for work. The studio brass became so desperate that on Friday, June 8, they ordered a story released to the press stating they were going to sue Marilyn for half a million dollars for delaying production. They would also replace her with another actress, and this would be the end of Marilyn’s career.

When Marilyn heard, she was shocked. She couldn’t believe what the studio was doing to her. She said, “It’s all right when the Fox executives get sick. They can stay home. But Marilyn, what right has she to get sick? Those bastards, how could they do this to me, after all the millions I’ve made for that studio?” Finally the Fox executives decided to suspend Marilyn and shelve Something’s Got to Give until further notice.

That very weekend Marilyn and I began working on our Cosmopolitan and book projects. This would keep us busy, and I hoped it would keep Marilyn from thinking about her problems with the studio. She had asked me to shop for clothes for her to wear in the photographs, and I also had to locate a house for our sessions, since Marilyn’s was unfurnished. She was still waiting for the arrival of furniture she had bought in Mexico some time ago.

On my shopping spree for Marilyn, I went to two of her favorite stores, Jaks on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills, and Saks Fifth Avenue. At Jaks I bought her some beautiful slacks and decorative Emilio Pucci sport shirts. Then off to Saks for a bulky sweater, terry-cloth threequarter hooded beach jacket, a blanket, a large towel for those peek-a-boo beach shots, and a sexy bikini. I did not buy Marilyn any undergarments—she never wore them.

My friend Tim Leimert was willing to let us use his house, located in the North Hollywood Hills, providing I would introduce him to Marilyn. Tim’s home was beautifully furnished with expensive paintings and sculpture. He also had a huge garden and patio. Only a swimming pool was missing—but Marilyn’s house had one—so the high quality of our backgrounds was assured. Tim promised not to hang around while I interviewed and photographed Marilyn.

When Marilyn and I got to Tim’s house, I introduced him and his maid, Louise, to Marilyn. Louise became so nervous when Marilyn shook her hand that she fluttered and stuttered, saying, “Is that really you? No one will believe me when I say I met and shook hands with Marilyn Monroe. I can hardly believe it myself. Is that really you?”

Marilyn, laughing, replied, “Sometimes I can hardly believe it, too.” Tim kept his word, and soon afterward, accompanied by the still flustered Louise, he left his house.

So, for the weeks from June 9 until July 18, I was busy working with Marilyn. I had taken a group of indoor and outdoor shots, including a series at Santa Monica beach, and I had interviewed Marilyn at length for our Cosmo story and for our book. She was wonderful to work with the entire time; she never looked more beautiful, nor was she ever so talkative. Our book project was more important than ever to her after all those lies the Fox studio had handed out to the press. The media didn’t even have the common courtesy to tell her side of the story.

I returned to New York July 20 to work on our projects and was spending the weekend in the country with my family. On Sunday I drove my brother-in-law to the local general store. I was waiting outside in the car when my brother-in-law came running out, shouting to me that he’d just heard on the radio that Marilyn Monroe was dead, at the age of thirty-six.

After Marilyn’s death, the press was constantly hounding me for interviews about Marilyn, especially since I had seen and spoken with her so shortly before her death. To escape the pressure I fled to Paris, where I remained for over twenty years. I married a French actress, Sylvie Constantine, and we have two lovely daughters, Caroline and Stephanie. In 1982 I moved back to the United States with my family, and we settled in the Los Angeles area. My family was eager to see where Marilyn was interred, so I took them to visit her crypt, where I introduced them to Marilyn. We all said a prayer for her—she had become part of our lives.

Why have I waited all these years before deciding to have this book published? I was in a state of shock after Marilyn died. Of course I wanted to keep our last conversations and many of her photos private. But now that I have grown older and wiser, I realize that Marilyn belongs to the public and her millions of fans.

She was in great spirits in her final days. She was full of life and couldn’t wait to get started on the next phase of her career. Although none of her husbands or friends seemed to bring her the happiness she was seeking, I will never believe that she took her own life. It will always be my conviction that she was murdered. But no matter how she died, we all lost her too soon. I hope this book brings you pleasure, as she did.

—GEORGE BARRIS