5

“I THOUGHT I WAS TOO COLD, FRIGID”

Let me tell you more about how my marriage to Jim Dougherty developed. When I was still fifteen Aunt Grace decided to get me off her hands, even though she was my legal guardian. The best way she thought was for me to get married. I remember her telling me, “Norma Jeane, you really are now quite a mature woman,” and that it was time for me to think about marriage.

Wow. This really frightened me. I had never thought about marriage. You know, going with boys was fun and all that, but marriage, no. I was only fifteen. Maybe I looked like a woman, but I was still a kid. I protested to Aunt Grace. “But I'm too young,” I pleaded. Her answer: “Only in years, only in years. You're really quite a mature woman, even though you are only fifteen.” It was all my aunt Grace's doing; she instigated my marriage to Jim Dougherty. Jim was older—around twenty-one, going on twenty-two.

We dated for several months to get to know each other better. I never had an engagement. And just three weeks after my June first birthday was when we had our double-ring ceremony. Marriage to Jim brought me escape at the time. It was that or my being sent off again to another foster home. Once more it was the case of not being wanted. It wasn't fair to push me into marriage. What did I know about sex? When I told Aunt Grace I was frightened of what a husband might do to me, she seemed quite surprised at my innocence.

What shocked me the most then was finding out before marriage that I was an illegitimate child! Then finding out for the first time the true facts of life. My aunt Ana bought me a book that contained the facts and hints a bride-to-be should know. I had told my aunt Grace I didn't feel confident that I could be a good wife. I thought I was too cold, frigid.

After our marriage, Jim said I was a most responsive bride, perfect in every respect—except in the cooking department. I was a warm, loving wife. If only I could cook.

GEORGE BARRIS: When Marilyn turned sixteen, she was practically forced to get married. Otherwise she probably would have had to live in another foster home. Jim Dougherty seemed a nice enough sort of young man. Yes, she said, he was a nice, caring person—but marriage at age sixteen for the rest of her life? Didn't loving your husband count? What about the intimate part of marriage? Sex and marriage no doubt scared the life out of Norma Jeane. She was still a virgin. Maybe she did let the boys kiss her, maybe she even petted a little—but that was all. It didn't mean she was ready to be a bride. She and Jim did as best they could.

Marilyn and Jim spent many of the early days of their marriage at Santa Monica's “Muscle Beach,” which was famous for its

Jim never wanted me to become a model or actress. In fact, he never encouraged me in any way. He would discourage me by telling me that there were plenty of beautiful girls that could sing and dance and act. Hollywood was full of them. They're all looking for work. What, he would say to me, what makes you think you're any better than them? I don't think he really knew how I felt.

It was 1944, during World War Two, that Jim enlisted in the U.S. Merchant Marine. After his boot training he was stationed at Catalina Island, not far from where we had been living in Los Angeles. He was a physical training instructor there, and the best part was I was able to join him. It was a world of men, all sailors with their wives and families. I didn't mind it being a world of men as long as I was a woman in it. You never saw so many sailors, so many men.

Besides the sailors there, [there were some] marines, Seabees, coast guardsmen—but not too many girls. I was always true to my husband, but he seemed jealous and annoyed when the men would whistle at me. He would lecture me about the type of clothes I was wearing. Actually, I wore the same clothes the other girls wore, you know, tight sweaters, shorts, and what Jim would call bathing suits. I just couldn't understand his acting that way.

population of handsome men who gathered there to show off their feats of strength. Theyoung couple would relax and watch the muscle men perform. When Jim was not around, many of those young men would flirt with Marilyn and ask her for dates. All she had to do to discourage them was to smile and flash her wedding band, saying “Sorry.” She was faithful in those days.

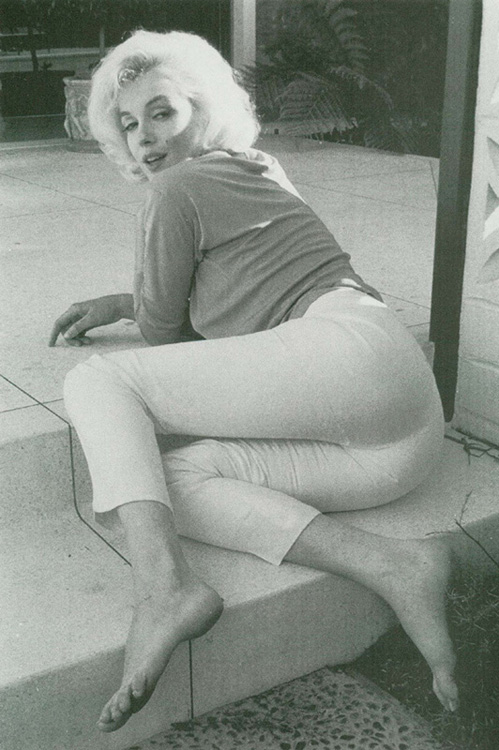

Photographing Marilyn, I sometimes wondered how she could possibly be faithful to one man. As she would say, “I wish there were more of me to make all those men out there happy.” I often thought she had been blessed with too much in this world; men desired her and women were envious of her beauty. I hoped her life would bring her happiness someday.

When Jim was shipped to Shanghai, I went back to Van Nuys to live with his family. I got a job at the Radio Plane plant in Burbank [a defense plant]. They started me there as a parachute inspector, and later I was promoted to the “dope room,” where I would spray this liquid dope, which is made by mixing banana oil and glue, on the planes' fuselages. These were miniature planes used for target practice. The dope was sprayed on the fuselage to give it strength. I worked in overalls and kept my head covered most of the time so that the dope wouldn't get into my hair, since it was messy and difficult to wash out.

Well, one day an army photographer came to our plant. He was from the army's pictorial center in Hollywood. His assignment was to take pictures for the army newspapers and magazines of people working in defense plants, showing them doing their share in the war effort. He called them morale-booster photos. I was later told most of these photos were of pretty girls at work.

So when this army photographer, David Conover, passed by where I was working, he says, “You are a real morale booster. I'm going to take your picture for the boys in the army to keep their morale high.” I didn't know what he was talking about at that time, but he later explained it to me. First he took pictures of me in my overalls, but when he discovered I had a sweater in my locker, he asked if I would mind wearing it for more pictures. He said, “I want to show the boys what you really look like.”

Those pictures he took of me were the first that ever appeared in a publication. They appeared in hundreds of army camp newspapers, including the army's famous Yank magazine and Stars and Stripes.

When David Conover phoned me a few weeks later, he said he had shown my pictures to a commercial photographer friend in Los Angeles and if I was interested in modeling he would like to see me. I soon called the photographer, Potter Hueth, and made an appointment to see him. At his studio he explained to me that he couldn't pay me for modeling then, but if I wanted to speculate with him he would take pictures of me

and when he sold them to the magazines he would pay me. The fee, he said, was usually five to ten dollars an hour, which was a lot of money in those days.

What did I have to lose? So I agreed, providing I could pose at night so as not to lose time from my job. That was okay with him. I worked at his studio several nights. He told me I had that natural look. I told him I always tried to be natural. Secretly I'd always wanted to be a photographer's model. Maybe this would be the beginning for me.