An Appreciation

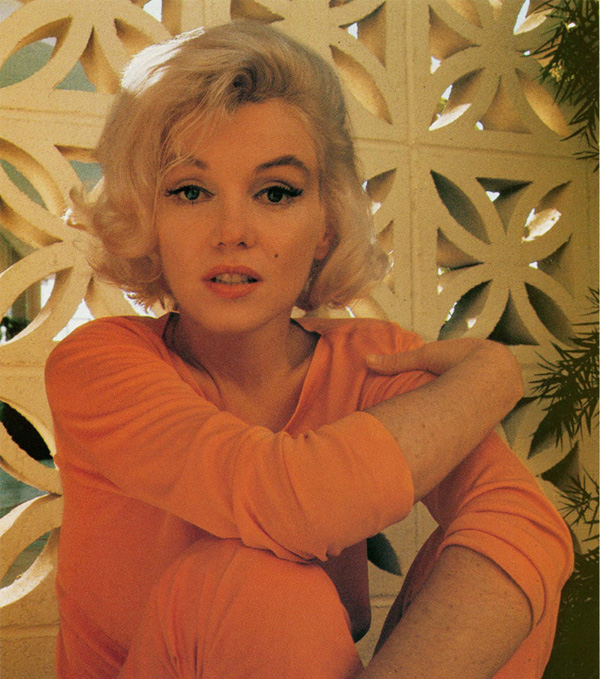

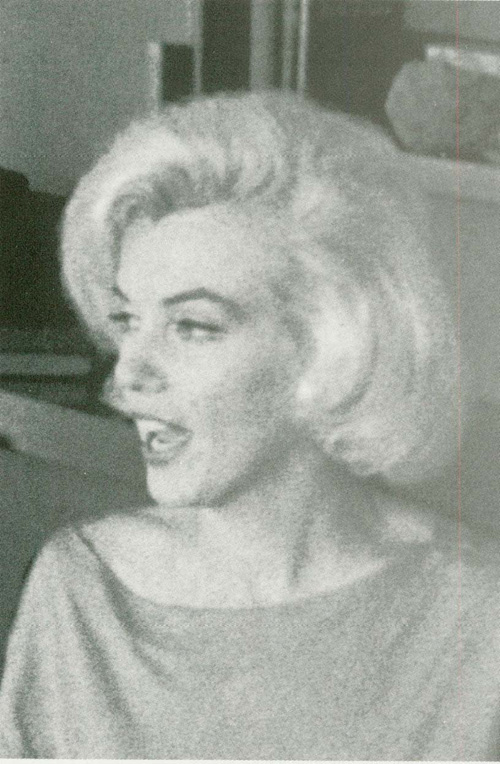

THAT SUNDAY IN JUNE 1962 when I rang Marilyn’s doorbell for the first time, she appeared in a blue-gray Turkish bathrobe that matched her sparkling blue-gray eyes. She held a half-full glass of champagne that caught the sunlight. Even though the robe was tightly wrapped around her body, it could not conceal those famous curves; clearly she wore nothing underneath. She spelled s-e-x from the top of her golden head to the tips of her toes. She had a peaches-and-cream complexion and a fabulously sexy voice. Here was every man’s dream of the sexiest woman in the world. I could hardly believe my eyes—this beautiful creature had turned thirty-six on June 1—it seemed that the older she grew, the younger she looked. The first thing she said to me was, “Hi,” and then she offered an open smile and invited me to come in.

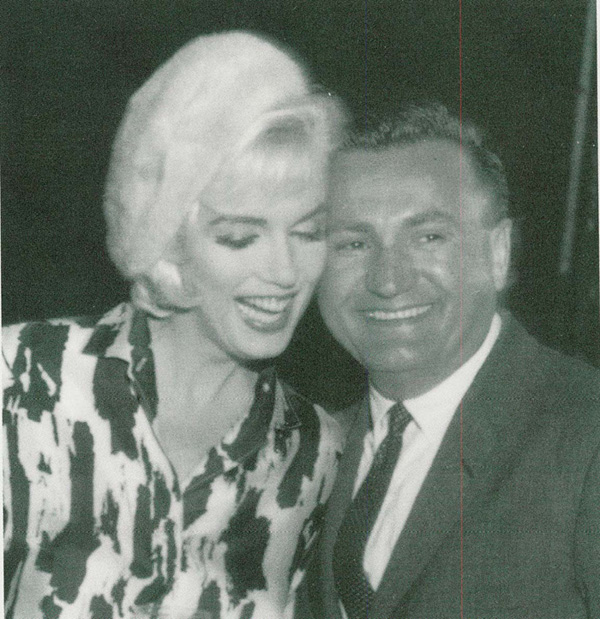

I was there because Marilyn had finally found time for us to work on our photoessay for Cosmopolitan and make some headway on our longdelayed book project. I was to interview Marilyn at home for our book, and she had suggested I bring along a tape recorder. So, along with the (borrowed) recorder, the most beautiful single rose I could buy, and a bottle of her favorite Dom Perignon, I had rung her doorbell, prepared to tape our exclusive interviews.

Marilyn went into the kitchen to get me a beer, and when she returned, we made ourselves comfortable. It turned out that she had changed her mind about talking on tape. She said it made her nervous; she’d be on guard and not able to speak freely. She thought she could give a more intimate interview if I just took notes—and then later on I could fill in the details of our conversations.

Of course I was disappointed, but what she said made sense to me. I

began to realize that she was a very smart woman who knew exactly how she wanted to work with me. I was going to play by her rules on our project; she would call all the shots. So I agreed and sat back in her new home, the first she had ever owned, to toast her and our project. She said, “Now that I’ve turned thirty-six, this is a dream come true for me—my having my own home, my own house. I have an apartment in New York City on Sutton Place, and I’m officially a legal resident of New York, but since pictures are still made in Hollywood, that’s where I have to be for work. I decided it was time for me to buy a house, instead of leasing one all the time… It’s a cute little Mexican-style house with eight rooms, and at least I can say it’s mine—but not alone. I have a partner.”

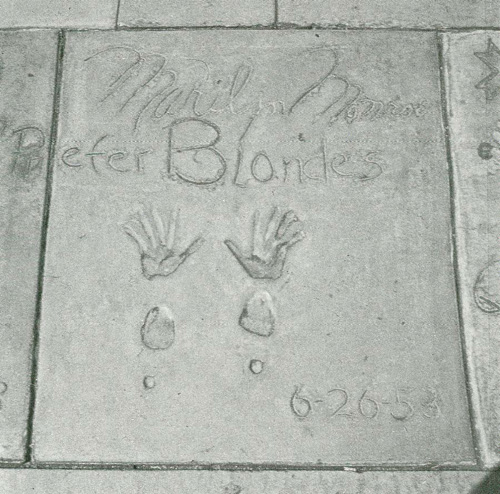

When I asked her who that might be, she said, “The bank! I have a mortgage to pay off. There’s a six- or eight-foot wall for privacy, and my mailbox has no name on it, but the mailman knows who lives here. I don’t know if you noticed there are fourteen red stone squares leading to my front door, where there is a ceramic-tile coat of arms with the motto CURSUM PERFECIO, meaning ‘end of my journey.’ I hope it’s true. What’s great, too, is that this house is near the ocean and the studio. The address is cute, too: 12305 Fifth Helena Drive, Brentwood. And get this, I’m in a cul-de-sac or, as we call it, a dead-end street. It’s small, but I find it rather cozy that way. It’s quiet and peaceful—just what I need right now.

“I want to give small dinner parties for my friends where we can relax and have some good times. I live here all alone with my snowball, my little white poodle—he was given to me by my dear old friend Frank Sinatra. I call him Maf. Oh sure, it gets lonesome at times living alone; I’d rather be married and have children and a man to love—but you can’t always have everything in life the way you want it. You have to accept what comes your way. I live alone and I hate it!”

This friendly, cordial woman seemed nothing at all like a Hollywood power to reckon with, didn’t act the stereotype of the star at home. She made me feel welcome right away. She had just recovered from another of the numerous illnesses that had caused Fox to suspend her from work on Something’s Got to Give, and I could hear sadness in her voice and see it on her face as she described the many “friends” who had deserted her in this crisis.

Later on, we began our photo sessions in the borrowed house in North Hollywood that would stand in for Marilyn’s new Brentwood home. Brentwood was near Beverly Hills and Hollywood, but it could have been a million miles away as far as Marilyn was concerned. Although she would have no doubt preferred to be photographed in her own home, I thought its barely furnished condition made it a bit depressing.

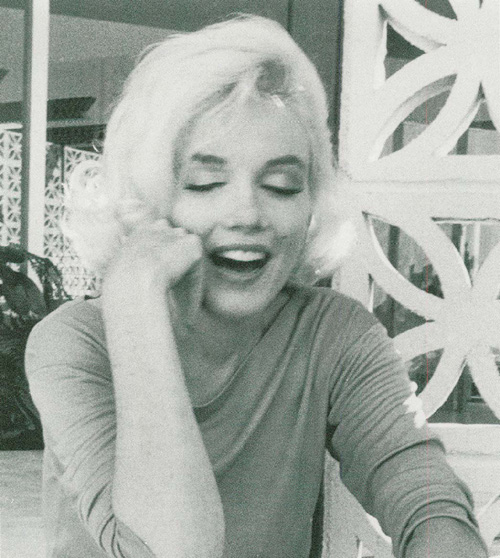

As I took pictures of her in Tim Liemert’s lovely home, Marilyn would now and then lapse into a blue mood. She would cover her face with both hands, lower her head for a moment or two, and then, smiling, become her old self again—cheerful and clowning for the camera. But I could see a residual tear or two.

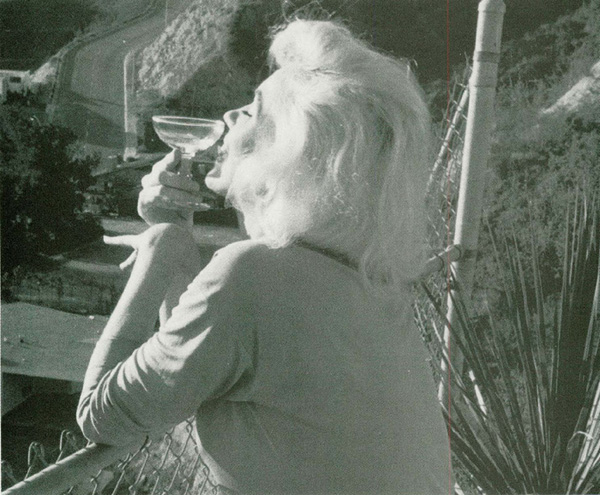

Once she walked out into the garden, with its panoramic view of Los Angeles below. Holding her glass of champagne, she lifted her face to the sun and toasted the city where she’d been born, grown up, and had her successes and her failures.

As we talked on there, Marilyn told me she loved the beach, and when I suggested we take a series of photographs at the Santa Monica beach, she was thrilled. That particular beach brought back memories of her childhood, when she had spent many wonderful days there with her mother and her friends.

In her younger days, Marilyn had often driven along the Pacific Coast Highway, enjoying the sunset or the moon’s reflection in the water. She might stop with a boyfriend at a small beachside restaurant, have a late dinner, and dance the night away. She might go down to the beach, kick off her shoes, roll up her slacks, and let the cool water caress her feet as she and her friend walked along the sand in the moonlight. “It was sometimes better than sex,” she said.

She had continued to enjoy these nights on the beach, and on such stops after she’d become a star, she needed to disguise herself in order not to be mobbed by fans. Even though she was most often dressed in a baggy sweater and slacks, with a scarf over her hair and huge sunglasses over her eyes despite the darkness, a fan might come up and ask, “Did anyone ever tell you, you look just like Marilyn Monroe?”

Marilyn would laugh and reply, “All the time.”

She wasn’t the only Californian who loved the beach—there were plenty of others who often spent whole days there, so finding a quiet, uncrowded area was a problem when we went there, but we finally located a place the other beachgoers had overlooked. The spot was near the old Peter Lawford house, where rumor has it Marilyn had trysted with John Kennedy and later with his brother Bobby. If Marilyn noticed, she didn’t say so.

I was surprised by the respect Marilyn’s fans showed her during the sessions at Santa Monica beach. No one bothered us; the people who gathered around spoke in whispers.

Of course there were exceptions to the generally respectful treatment by the fans: A very regal lady once paraded majestically into camera range and, with a slow sideways glance, indicated that it would be perfectly okay to include her in a photo or two. On another occasion, a couple of picnickers positioned themselves for a clear view of our work and politely asked anyone blocking their front-row view of the star to please move on. The teenage boys were the funniest—they would mimic Marilyn’s sultry poses, much to their own amusement, as well as our own.

But the “mystery lady” intrigued us. Wearing a large straw hat that concealed her face, she stood silently and almost motionless as she watched the goings-on. All of us wondered who this presence might be. Sometime later, when I was visiting Mae West, she revealed that she had been the mystery lady. Although she’d never met Marilyn, the sex queen of years gone by was an admirer of the work of the current sex queen. Mae West said, “Oh, if only I could have met her. It would have been such an honor to talk to her. She’s such a beautiful and talented actress.”

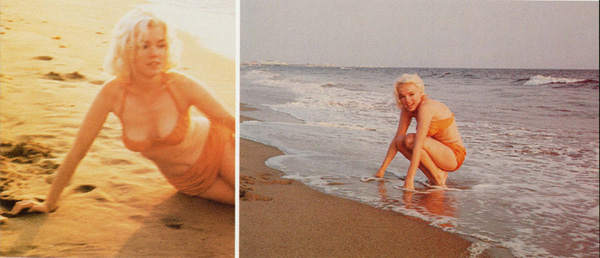

But the hero of our picture days at the beach was Marilyn herself. Photography is hard work for the photographer but even harder for his model. Both of us wanted every picture to be as exciting, unusual, and yet natural as could be. We worked as a team, and both of us came up with ideas for the pictures. As a former photographer’s model, Marilyn was a pro posing for the still camera—and that shows clearly in the pictures I took of her then.

We were both relaxed during our beach shoot, and some of our best photos were taken there. The Santa Monica beach photos were Marilyn’s favorites among all those I took of her. They may well have reminded her of the ones that had been taken when she was just nineteen, top model at the Snively agency and dreaming of becoming a star.

The weather during June and July 1962 was often cloudy, with occasional bursts of sunlight. I liked photographing in this type of light. The clouds encouraged the soft light I wanted for the moody, reflective experiences I thought appropriate to that time in her life, while the sunlight produced the cheerful days she was to recall in other photos.

Marilyn was often late for our photo sessions. One day I waited for her for what seemed like hours, when suddenly she appeared on the beach with a strange-looking hairdresser and an even stranger-looking makeup man; the car was filled with clothes. I knew she never traveled with an entourage, so these two had to be her faithful friends, Agnes Flanagan and Allan “Whitey” Snyder, who were constantly at Marilyn’s beck and call. (This time she hadn’t brought along the third member of her “family,” Pat Newcomb, who handled Marilyn’s press and acted as her majordomo. She handled Marilyn’s wardrobe and her fans, but was much more than an employee; she was a best friend. She was ten years younger than Marilyn, but I couldn’t tell the difference in their ages; both looked much younger than they were.)

On this day, the sun had disappeared over the horizon and the sky was turning dark. She looked at me with tears in her eyes. “I’m sorry,” she sobbed. “Is there any way you can take the pictures without light?”

How could I get angry at her? There was always an excuse, and I was sure it was legitimate. I gave her a hug and said not to worry, we’d do it another day.

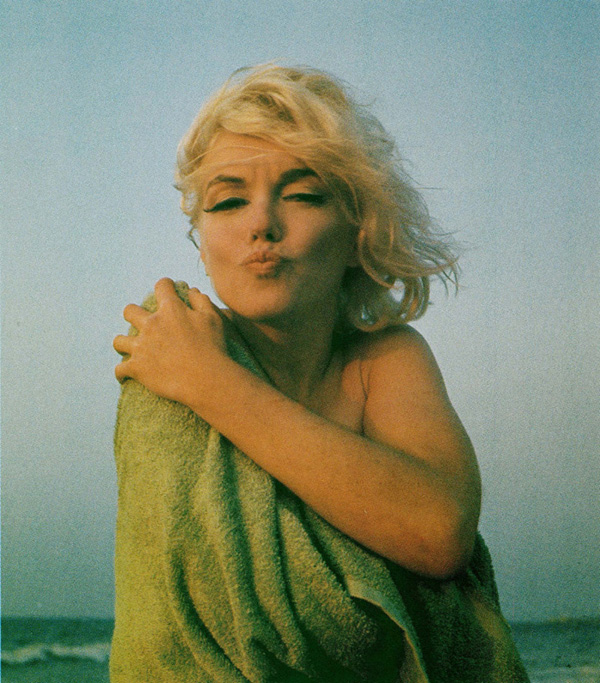

And to prove her sincerity, the next time we worked at the beach she gave more than her all, with never a complaint, never a break. She was determined to make it up to me. Marilyn was a real trooper. Even when the sun went down and the winds blew and it became cold, and she shivered, her skin turned red and her lips blue, she hardly whimpered or complained. Only when the day was almost over and I had just one last bit of film in the camera, she said, “This is for you, George.” Then she puckered up her lips and blew a kiss my way as I took the last picture of her ever on that beach. It was around 7:30 P.M., Friday, July 13, 1962.

At the end of that same day I lost one of my shoes when a huge wave came and took it away. I asked her, “What do I do with one shoe?”

“The ocean apparently needs it more than you do,” she said, and with that, both of us barefoot, we left Santa Monica beach forever.

When I look at the contact prints of the black-and-white pictures I shot, I remember that Marilyn always checked the photos carefully. Once she said, “Can you make larger prints of those pictures I’ve marked so I can get a better look at myself?” As a reminder, she even marked those photos she selected on the contact sheet with a red grease pencil.

She would spend hours scrutinizing pictures of herself and, of those she especially liked, she would sometimes loudly remark, “Now, that’s really me!” Her experience as a photographer’s model had taught her to appreciate how she photographed. She was such a perfectionist that even if only a hair was not in place in a photo she would become upset. “We should have waited for the wind to stop blowing so hard—next time, let’s remember this,” she might remark.

We were trying to re-create various stages of her life in those pictures. Even in the photographs meant to show her in her adult years. One day I noted that little Norma Jeane appeared in many of them, and I said,

“There always will be the little girl in Marilyn Monroe.” Her reply was a broad smile.

She never told me not to print or use any photos of her in our book, in other publications, or in any other way. The markings she made were meant to indicate the pictures that contained no defects. She wanted me to make large prints of those photos for her. She said that those pictures were some of the best and most natural ever taken of her. “That’s really me, freckles and all. The real me.”

* * *

When my brother-in-law told me that Marilyn was dead, only days before I was to meet her again in Los Angeles, I broke out in a cold sweat. I felt a pounding in my chest, and for a few seconds I couldn’t respond. Then I said, “Come on, Frank, don’t make bad jokes. I just spoke to her; I’m going to the coast to see her on Monday.” I knew I had to get back to New York City to find out what had happened.

I drove the hundred miles to my Sutton Place apartment at record speed. The doorman said reporters were asking for me. The elevator couldn’t get me up to my apartment fast enough. As I opened the door, I could hear the phone ringing. I turned on the radio and television. All the stations were blaring the news of the death of Marilyn Monroe, how it appeared to be a suicide. The press wanted interviews with me; the phone didn’t stop ringing. It’s not true, I said to myself, I don’t believe it. But it was true. We’d last spoken on August 3, 1962, only one day before she died.

* * *

My phone kept ringing all night long. Friends were calling—more press. I had nothing to say.

Monday morning, after a sleepless night, I went to the office, simply because I couldn’t think of anything else to do. It was only eight o’clock when I got there. The office was empty—the staff didn’t arrive until ten. I sat at my desk half asleep. The phone rang. It was Stan Mays, the local correspondent for the London Daily Mirror. Stan worked out of the New York Daily News editorial offices on a reciprocal arrangement. He sounded frantic. He had been trying to locate me and wanted me to come over right away with my interviews and photos of Marilyn. I told Stan I was still working on my Cosmo story and the book. I said I’d get back to him, but Stan insisted, “Just get over here as soon as you can.”

I finally reached the Cosmo editor, Bob Atherton. He said, “Not only is Marilyn dead—so is your story. By the time we come out in November it will be old news. George, your story is now hard news. In respect to Marilyn, let her story finally be told to her fans and the public, those mil- lions who loved her.” I wondered whether Marilyn would want me to tell it. I retrieved my photos and text from Cosmo and from my office and then walked the short distance to the Daily News to see Stan. I was still in shock, still groggy from a sleepless night.

After looking at the text and photos, Stan immediately picked up his phone and called his editor in London. He whispered into the phone, “I finally tracked George Barris down; his photos and interviews on Marilyn are sensational.” The rest of Stan’s phone conversation was brief. When he hung up, he said, “The boss wants you to fly out to London right away with your story on Marilyn, all expenses paid, to negotiate exclusive one- time British rights.”

Before I quite realized what was happening, I was on a plane to Lon- don. When I arrived, a limousine was waiting for me at Heathrow, Lon- don’s main airport. It was early Tuesday morning as we sped off to the London Daily Mirror Building, escorted by three burly reporters. I was told later they were there to guard me from being kidnapped by the com- petition, a newspaper called News of the World, that was desperately seek- ing my story. That seemed like something from a James Bond movie, but, then again, in London anything is possible.

The London Daily Mirror editor (I never did get his name) assured me he was mainly interested in my photos of Marilyn, since his paper was one that featured photos and few words. The story he wanted was to be about my working with Marilyn in those last days. I asked him not to sensationalize the story, and he promised not to use more than a dozen photos. He kept his word and played it straight.

I had spent less than an hour in the Mirror office, yet the editor assigned his top feature writer, Tony Miles, to accompany me to Los Angeles. Marilyn’s funeral was to be the next day, Wednesday, August 8, and the editor promised I would be back in time.

It was still Tuesday morning when we left. I had been in London less than three hours when our plane departed for Los Angeles via New

York. Tony was assigned for further interviews with me since the Mirror planned to run the Marilyn story over several days.

Our plane arrived in New York late Tuesday evening. There were no direct flights from London to Los Angeles in those days. With a change of planes we arrived in Los Angeles around three Wednesday morning, just enough time to check into the Beverly Wilshire Hotel and catch a few hours of needed rest. I left the hotel around noon to attend Marilyn’s funeral at the Westwood Memorial Park. It was a short limou- sine ride, but when I got there the services had already started and the chapel door was closed. I could not enter.

As I waited outside for the services to end, some members of the press noticed me, one reporter yelling, “Hey, George, how come the spe- cial treatment?” The press was roped off from the chapel and the crypt, Marilyn’s final resting place. I walked over to the reporters and replied quietly, “I’m here as a friend of Marilyn’s—see, no notebook, no cam- era.

After the services I followed the funeral procession the short distance to the crypt, where Marilyn was to be laid to rest. Joe DiMaggio, her sec- ond husband, had made the plans for Marilyn’s funeral but invited only a few close friends. Her first and third husbands were not there.

DiMaggio had decided not to invite the Hollywood crowd of movie stars. When Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra, and many other celebrities tried to attend, they were refused entry. They loved Marilyn and could not understand DiMaggio’s attitude. But Joe blamed them for Marilyn’s death, thinking them responsible for her careless lifestyle.

At the crypt prayers were said for Marilyn with tears and sobs from the mourners. Noticeably absent was Marilyn’s mother, Gladys, who was under the care of Marilyn’s half sister, Bernice Miracle, and remained in Florida because of her mental condition. When Gladys learned of Mari- lyn’s death, she said, “I never wanted her to become an actress.”

When I returned to the hotel after the services for Marilyn, I found a phone message from the editor of the New York Daily News. He wanted me to call him as soon as I could. He asked that I return to New York City as soon as possible. He wanted my Marilyn story and was upset that I was in his editorial offices, right under his nose, and the London Daily Mirror had beaten him to the punch. “Wait until I get my hands on Stan Mays,” he shouted into the phone.

Tony Miles and I caught the afternoon flight for New York. We were met at New York’s La Guardiã airport by a team of Daily News reporters who wisked us off in a limo to the New Weston Hotel on 48th Street between Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue. We were kept away from the Daily News so that the competition could not get my story. Again, I was reminded of a scene from the famous Broadway play The Front Page, in which newspaper competition for a front-page story had reporters hiding their source from their competitors.

The News assigned Theo Wilson, their top byline feature reporter, to the Marilyn story. Like the London Daily Mirror, the Daily News empha- sizes photos in its stories.

The London Daily Mirror series started Wednesday, August 8, 1962, and ran for four days. The New York Daily News story began on Tues- day, August 14, 1962, and ran for a full week. Each newspaper had the largest circulation in its country; yet only ten percent of my text inter- views with Marilyn Monroe appeared in these stories and only a dozen photos were used.

During August 1972, a photo exhibition called “The Legend and the Truth” was held at the David Stuart gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles. The exhibition consisted of photographs of Marilyn taken by a dozen topflight photographers, including myself. The exhibit was a huge success; Life magazine did a cover story with an eight-page spread. Many book publishers became interested, and that same year Grosset and Dun- lap published a book based on the exhibit and titled Marilyn, with a text by Pulitzer Prize—winning author Norman Mailer. The book featured photographs by twenty-four of the world’s foremost photographers and was produced by Larry Schiller, one of those photographers. Only ten of my photos appeared in that book (five in color and five in black and white). No text of mine or Marilyn’s appeared there.

The book instantly became a worldwide bestseller. The publisher’s editor in chief (and vice president), Bob Markel, later became my agent. Norman Mailer had never met Marilyn, and his text consisted of his impressions of Marilyn combined with the impressions of others. Mailer, a friend of Marilyn’s former husband, Arthur Miller, had asked Miller to introduce him to her several times. Marilyn had refused to meet him. She just didn’t like his style.

In 1965 Richard Seaver, president and editor of Henry Holt and Company, was eager to publish a book about Marilyn Monroe from a woman’s point of view. Seaver hoped to interest a writer in explaining Marilyn as an individual and as an icon. Gloria Steinem, cofounder of Ms. magazine and a leader in the women’s liberation movement, and I were brought together by Seaver. His idea was to use some of my pictures of Marilyn (and some by other photographers’) and to have Gloria explore the viewpoints of women influenced by Marilyn, to identify who those women were and how they’ve become important, and ultimately to indi- cate how Marilyn was ahead of the women of her day.

Steinem, Seaver, and I agreed to create a special fund to help chil- dren in need, including those who are emotionally disturbed. Steinem’s fee as a writer and a portion of my royalties and the publisher’s profits were to make up the initial fund. Readers were invited to contribute, too.

The Steinem book, called, Marilyn—Norma Jeane, was published in 1986 and made the New York Times bestseller list. It contained eighty-two of my photos of Marilyn (fifty-five in black and white and twenty-seven in color). Steinem used brief quotes from my last interviews with Marilyn, along with many other sources. (Steinem herself had once briefly encoun- tered Marilyn at the Actors Studio in New York.)

* * *

Compiling this edition of Marilyn has brought back many memories, both happy and sad. I hope that the spirit that I think shines through in these photographs of a complex and delightful woman will bring memo- ries and joy to the readers of this book.