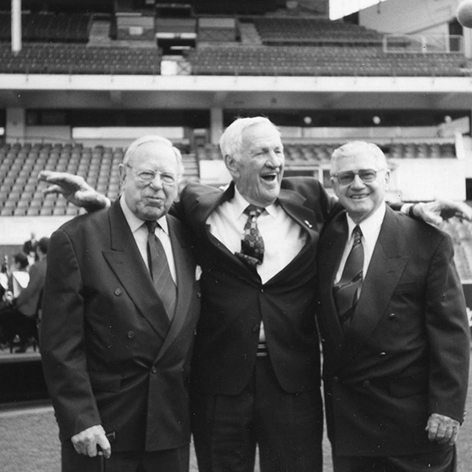

Invincible: The unveiling of the Bradman statue in Melbourne in May 2003 brought three of his old ‘Invincibles’ teammates to town. From left: Arthur Morris, Sam Loxton and Neil Harvey. ‘Arr,’ said Sam, taking centre stage, ‘the rose amongst the thorns!’ Bruce Postle

B

‘Tell your little mate,’ said Bradman, ‘that you can’t get out if you hit the ball along the ground…’

BATTING ROYALTY

They ruled peerlessly for almost two decades, beacons in a top six as distinguished and prolific as any in history: Rahul Dravid from Karnataka and Sachin Tendulkar, Mumbai. They cornered the No. 3 and No. 4 positions in India’s batting order for 15 years, sharing in a record 20 Test and 11 One-Day International century stands.

The pivotal pair in India’s charge to No. 1 in the Test rankings in 2009, they pillaged and pummelled opposing attacks world-wide. Dravid, ‘The Wall’, seemingly impregnable, the grand master of crease occupation, and Tendulkar, the best since Bradman, imperious, inspired, wristy, formidable.

Along with fellow batting ‘Dons’, VVS Laxman and Virender Sehwag, they provided Indian bowlers with a consistent springboard of runs from which to defend. No other pair in the history of Test cricket has amassed more runs and only a few had their average of 50 runs per partnership.

In the Christmas Test in Melbourne in 2011–12, their twentieth Test century stand momentarily threatened Australia’s superiority. On their dismissal, India capitulated, never to recover. Tendulkar’s 73 was a masterly cameo that few of us wanted to see finish. To the first ball after an interval from expressman Peter Siddle, he deliberately deflected a lifter over the top of the slips cordon all the way and over the third man rope for a miraculous 6. It was a shot of genius, a reminder of the Little Master’s halcyon best. He played with all his flowing precision before being castled late in the day by Siddle – arguably the most important ball bowled all summer.

The applause accorded Tendulkar Australia-wide, stretching into the one-dayers, was loud and generous. His place only just behind Don Bradman as cricket’s finest batsman was simply indisputable.

Dravid, too, was admired for his mental toughness and unflappable ways, a rock every other Test nation would have loved to have had at No. 3. Even as a 38-year-old in 2011, he amassed five centuries in a calendar year, including three against the No. 1 ranked team in the world, England.

When Dravid and Tendulkar shared in century stands, India invariably won. No pair seemed as certain or as composed. It was as if their bats were broader than everyone else’s. Their most prolific period together came in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when they combined in four century stands, including three doubles in two home seasons. In back-to-back Tests, Heath Streak’s 2000–01 Zimbabweans conceded 525 runs to the pair in three innings.

Their ODI partnerships in this period were also significant and featured a triple-century for the second wicket against the visiting New Zealanders at Hyderabad.

The pair always seemed at ease with each other, Dravid satisfied to play a back-seat role when Tendulkar was on song, which was most of the time. He always marvelled at Tendulkar’s passion for practice, his balance and unerring focus, believing Tendulkar’s success as a teenager had quickened the advancement of several of India’s other champions, especially Sourav Ganguly. India was fortunate to have so many of the great stars of the game.

Dravid also had a massively successful pairing with Laxman, the two averaging 51 and sharing 12 century stands in Tests. Tendulkar and Ganguly also teamed together brilliantly at one day level.

|

TEST CENTURY STANDS BETWEEN RAHUL DRAVID AND SACHIN TENDULKAR |

|

|

Stand |

Result |

|

170 v West Indies, Bridgetown, 1996–97 |

Lost |

|

163 v West Indies, Georgetown, 1996–97 |

Drawn |

|

113 v Australia, Chennai (Chepauk), 1997–98 |

Won |

|

140 v Australia, Calcutta, 1997–98 |

Won |

|

109 v New Zealand, Hamilton, 1998–99 |

Drawn |

|

229 v New Zealand, Mohali, 1999–00 |

Drawn |

|

213 v Zimbabwe, Delhi (FSK), 2000–01 |

Won |

|

249 v Zimbabwe, Nagpur, 2000–01 |

Drawn |

|

169 v Australia, Chennai (Chepauk), 2000–01 |

Won |

|

124 v West Indies, Port-of-Spain, 2001–02 |

Won |

|

163 v England, Nottingham, 2002 |

Drawn |

|

150 v England, Leeds, 2002 |

Won |

|

138 v Australia, Sydney, 2003–04 |

Drawn |

|

122 v Pakistan, Kolkata, 2004–05 |

Won |

|

127 v Bangladesh, Mirpur , 2007 |

Won |

|

139 v Australia, Perth, 2007–08 |

Won |

|

222 v Bangladesh, Mirpur, 2009–10 |

Won |

|

119 v Sri Lanka, Galle, 2010 |

Lost |

|

104 v New Zealand, Nagpur, 2010–11 |

Won |

|

117 v Australia, Melbourne, 2011–12 |

Won |

|

And their most memorable ODI stands: |

|

|

331 v New Zealand, Hyderabad, 1999 (in 46 overs) |

Won |

|

237* v Kenya, Bristol, 1999 World Cup (29 overs) |

Won |

|

*unfinished |

|

|

MOST CENTURY PARTNERSHIPS IN TESTS |

|

|

20 |

Rahul Dravid and Sachin Tendulkar (India) |

|

16 |

Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes (West Indies) Matthew Hayden and Ricky Ponting (Australia) |

|

15 |

Herbert Sutcliffe and Jack Hobbs (England) |

|

14 |

Mahela Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene (Sri Lanka) Justin Langer and Matthew Hayden (Australia) Justin Langer and Ricky Ponting (Australia) |

|

13 |

Andrew Strauss and Alastair Cook (England) |

|

12 |

Brian Lara and Ramnaresh Sarwan (West Indies) Sourav Ganguly and Sachin Tendulkar (India) |

|

11 |

Arjuna Ranatunga and Aravinda de Silva (Sri Lanka) Jacques Kallis and AB de Villiers (South Africa) Alastair Cook and Kevin Pietersen (England) David Boon and Mark Waugh (Australia) Desmond Haynes and Richie Richardson (West Indies) |

|

10 |

Sunil Gavaskar and Chetan Chauhan (India) Gautam Gambhir and Virender Sehwag (India) Rahul Dravid and Virender Sehwag (India) Rahul Dravid and Sourav Ganguly (India) Sunil Gavaskar and Mohinder Amarnath (India) Mahela Jayawardene and Thilan Samaraweera (Sri Lanka) Inzamam-ul-Haq and Mohammad Yousuf (Pakistan) Javed Miandad and Mudassar Nazar (Pakistan) Mark Taylor and Michael Slater (Australia) Marcus Trescothick and Michael Vaughan (England) |

BOSOM BUDDIES

Spencer Street railway station, Melbourne, January 1947: the Victorian team is assembling for its northern tour to Brisbane and Sydney. Captain Lindsay Hassett calls Sam Loxton over and points in the direction of the team’s teen star, Neil Harvey, and says: ‘You’d betta take care of the little bloke.’

And so began a happy 65 years together, which saw Loxton and Harvey become regular teammates at interstate and Australian level. They roomed together on two tours and later served as national selectors. They even linked up on the after-dinner speaking circuit, telling tall tales and true of life with Don Bradman’s fabled 1948 Invincibles.

They’d come from opposite sides of the Yarra, Loxton from prestigious Wesley College, where he was a champion cricketer and footballer; Harvey from the more humble backstreets of working-class Fitzroy. Sam was bold and opinionated and larger than life. He would have been the one in the wild west show to theatrically fling open the saloon doors to announce his arrival in town. Harv’s entrance would have been deliberately less dramatic. He always preferred to let his bat do the talking. Whereas Loxton would often bludgeon the ball to the fence, Harvey would caress it, relying on his footwork and exquisite timing.

Loxton had already celebrated his twenty-first birthday when he first opposed a 15-year-old Harvey at Brunswick Street. The kid caught him, after Sammy had made 66.

‘Even back then I was looking after him!’ said Sam, breaking into trademark gusts of laughter. There may have been seven years between them but they shared a chemistry, and remained inseparable right up until Sam’s death in 2011.

In Loxton’s debut Test, a virtual touring trial game against the Indians in Melbourne in 1948, he made 80 and shared a fourth-wicket stand of 159 with Harvey, who top-scored with 153 in only his second Test.

Loxton always thanked his lucky stars to have been included on the most famous tour of all, to England in 1948. He and Harvey were the two youngest in the chosen 17.

In the privacy of their room, Loxton said to Harvey: ‘How are we going to get a game in this [star-studded] side?’

Years later he told me: ‘I thought I was along for the ride, to pull the roller if the horse broke down.’

Circumstances were to conspire in both their favours. Keith Miller’s troublesome back saw the Australians one short in the pace bowling department, giving Loxton the break he needed from mid-tour. When Sid Barnes, fielding at short leg, was cleaned up by English tailender Dick Pollard, Harvey took his place and promptly made a fairytale century on debut.

Ironically, after a barren first month, Harvey asked Loxton to approach the Don and ask him what he was doing wrong. He was too shy to go himself.

‘Tell your little mate,’ said Bradman, ‘that you can’t get out if you hit the ball along the ground.’

In the epic fourth Test at Leeds, where Harvey made 112 and Loxton 93, sharing a century stand for the fifth wicket, the pair were batting together when Harvey stole his one hundredth run into the covers and had to shield his face to avoid being struck as the throw at the stumps came to his end. Loxton had sprinted through and doubled back almost as quickly to offer his congratulations. He was just as excited as Harvey.

Given that England had started with almost 500 and the Australians were 4–189 when Loxton joined his mate, their 105-run partnership was pivotal in Australia’s recovery. Loxton made 54 of the runs and Harvey 51.

‘It was always great batting with Nin [Harvey],’ Loxton said, ‘we have always been the greatest of pals. We roomed together for Victoria [from 1946] and on two tours for Australia [to England in 1948] and South Africa [1949–50]. He could do anything on the cricket field. He was a magnificent bat and I never saw him fall over in the field. He was magnificent. He had perfect balance whatever he did.’

On a crumbling Durban dustbowl in the first weeks of 1950, they shared their most significant stand, 145 for the fifth wicket after the Australians had slumped to 4–95 chasing 336 for an unlikely victory. The ball spun wickedly from the second day, South Africa’s Hugh ‘Toey’ Tayfield taking nine wickets for the game, including seven for 23 in the first innings.

Harvey mixed soft-handed defence with vicious square cuts and pull shots when it was safe. He’d never previously batted three sessions of a Test. In a wonderful career, this was to be his stellar five-and-a-half hours, his unbeaten 151 lifting Australia to an unforgettable victory.

‘The wicket was badly pock-marked. There were holes all over it,’ he said. ‘Their spinners, Tayfield and Tufty Mann [an orthodox left-arm bowler] were turning it a couple of feet and you never knew if the ball was going to stand up or shoot after hitting one of the crumbling holes. Sam’s 54 was so important for us. It was the innings of his life. We had to work for every run as Tayfield and Mann were so accurate [bowling more than 100 eight-ball overs between them].’

Loxton succumbed to Mann at 230 before Harvey combined with Colin McCool for another century stand to ensure the win.

‘We won a game we had no right to win, not on that wicket,’ said McCool.

The pair played the last of their 11 Tests together in 1951 and remained ever-so-close as Victorian Sheffield Shield teammates.

On the eve of one important state game in Sydney, the Victorians practised before deciding where to have lunch. Loxton was about to take off his boots in readiness to join them when Harvey interrupted: ‘No, Slox,’ he said. ‘You’re not playing well. We’ll get a pie [for lunch] and then I’ll bowl to you in the nets.’

‘And he did,’ said Loxton, ‘for two hours non-stop. That’s mateship for you. It was just wonderful. It was the way it happened in those days.’

Another time, at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, Loxton was batting with Harvey and was well set. One of his superstitions was never to look at his score on the scoreboard, so this day he asked Harvey how many he was.

‘Don’t ask me,’ said Harvey, who was short-sighted and struggled to see anything beyond 22 yards away. ‘Let’s wait to lunchtime and we get closer to the board.’

Their liaison continued in 1959–60 with Loxton as team manager and Harvey as player on Australia’s tour of India and Pakistan. Later, throughout the 1970s, they were national selectors and along with Sir Donald Bradman, responsible for the fast-tracking of icons including Rod Marsh and Dennis Lillee into Australia’s Test team during the 1970–71 summer.

‘We were running out of fast bowlers like nobody’s business in 1970 and we sat down for a meeting and the master [Bradman] said: “Seen any fast bowlers around the place? We seem to be getting frightfully short of them.”

‘Almost simultaneously Harv and I said: “As a matter of fact we have. There’s a kid in Perth called Lillee.”

‘“I haven’t seen him. Does he know where it’s going?”

‘“No, I don’t think so,” said Loxton. “But that shouldn’t worry us.”

‘“Why?”

‘“Because if he doesn’t know where it’s going, the batsman certainly won’t!”’

Dennis Lillee was chosen, took a ‘five-for’ on debut, the start of one of the great careers which was to net more than 400 Test and Supertest wickets.

In the early 2000s, Loxton and Harvey teamed up again, this time as professional storytellers, delighting audiences with their reminiscences from the 1948 tour. They told stories about the memorable boat trip to Dover, the shipboard games and antics, and having to buy dinner suits to dress up for dinner.

‘The only night you were allowed to appear [for dinner] in a lounge suit was Sundays,’ said Harvey.

Opening batsman Sid Barnes, one of only four survivors from the 1938 tour, had paid a kid a fiver to rubber stamp his signature on hundreds of team autograph sheets and sat back and enjoyed the view as the others developed writer’s cramp signing the sheets.

The Don spent much of his time downstairs composing his speeches for the many functions at London’s swishest addresses from the Savoy and the Dorchester to the House of Commons.

‘Don knew how good this team could be,’ said Loxton. ‘He put all this time into his speeches and never repeated himself even once. Not only was he the world’s greatest cricketer, he was one of the greatest after-dinner speakers as well.’

The Australians’ county game against Surrey at The Oval was a favourite moment. Harvey and Loxton opened the innings on the final afternoon and struck 122 in less than an hour to lift their team to a 10-wicket victory.

The RW Crockett bat with which Harvey had made his 112 on his memorable Ashes debut shortly afterwards had been borrowed from the Fitzroy Cricket Club, the only bat he owned having been broken during his Test debut in Adelaide.

‘I’d saved up some money and went into the Melbourne Sports Depot and bought this brand new cricket bat only for the handle to break within two overs [on debut],’ Harvey said. ‘I had to borrow one out of the kit after that.’

Following Harvey’s grand entry, one of the most pivotal in Australia’s magnificent seven-wicket win, Loxton took his mate’s bat to Bradman, saying: ‘This is the kid’s bat. Would you like to sign it?’

Bradman not only signed it but also inscribed it: ‘This bat is a symbol of a great innings by my friend Neil Harvey in Australia’s greatest victory, Leeds, 1948… Don Bradman.’

After a lifetime in the game, it remains Harvey’s most treasured possession. ‘I never thought I’d meet Don Bradman, let alone play with him,’ he said.

Their nostalgia shows were invariably sell-outs and often stretched into the wee hours. Invariably they’d leave us all laughing.

‘Just one more Nin… before we hit the road,’ Sam would say. ‘Can I tell this one?’ An hour later they’d still be talking, with everyone hanging on every word.

BOWLED SHANE

Without the mesmeric, compelling powers of Shane Warne, Ian Healy says he would never have been able to truly showcase his wicketkeeping talents.

‘It was always intriguing, challenging and good fun keeping to Shane,’ he said. ‘There was no batsman alive Shane didn’t think he couldn’t dismiss.’

As a young child from the Melbourne bayside, Warne developed extraordinary power in his wrists and fingers after breaking both legs. For 12 months he used a billycart to propel himself from room to room.

From the time one of the seniors at East Sandringham CC showed him how to flick a leg-spinner, he was soon astonishing them all with his talent to immediately implement what he’d been shown. The Warne leg-break, even then, would curve in the air and hum at the opposing batsman before biting and spinning wickedly towards slip. Mind you, that was only one in six and the all-weather wickets were much worn, encouraging extravagant spin. After he’d experimented for a while, he’d go back to his long run and pretend he was Dennis Lillee running through the Poms at the Centenary Test.

Having survived many a low point – one of his first captains at Brighton suggested he’d be better off concentrating on his batting as he didn’t think much of his bowling – Warne was identified as a teenager of uncommon promise and 702 Test wickets later – plus six more if you count an Exhibition ‘test’ in Sydney – he stands alone as Australia’s finest-ever bowler, ahead of Lillee, Lindwall, O’Reilly, Grimmett and even Glenn McGrath.

Healy, his first wicketkeeper, was also to become a world-beater. From tiny Biloela in central Queensland, he was five years older than Warne and had already been central in two Ashes campaigns before they first played in the same XI. He’d also survived rocky beginnings, when in his debut Test he dropped local hero Javed Miandad and watched with increasing despair as Javed made 210 and Pakistan batted into a third day at its cricketing citadel, Karachi. The rookie Queenslander also grassed a chance from Salim Malik and was certain his first Test would be his last. He was very much the baby of the team and had served a remarkably short apprenticeship. Greg Chappell had warned him that Pakistan would be the hardest tour of his life and, on return to Brisbane, Healy worked himself to a standstill, sharpening his footwork, glovework and fitness reserves with exhausting daily routines. Slowly his inner confidence returned, as did his form on the faster, bouncier, more-familiar Australian wickets. A chat with his hero Rod Marsh reinforced that he was heading in the right direction. Marsh liked the way Healy was staying on his feet and taking the ball on the inside of his body.

Healy had righted his career and was the unanimous choice as Australia’s No. 1 wicketkeeper when Warne was similarly fast-tracked, giving Healy the opportunity to excel standing up to the stumps, a true test of a wicketkeeper’s ability. They were to become a noted combination, Healy’s shouts of ‘Bowled Shane’ being picked up with the use of the stump microphones at the base of the wickets. It was to become one of Australian cricket’s best-known catch-cries.

With his wide smile, ample waistline and love of fags and fun, Warne had reminded Healy of an old bush player who didn’t care if he was hit for a six or two, as long as he eventually got the wicket he wanted. Even at 22, Healy regarded Warne as a champion, ‘And you can’t say that about most young blokes, no matter how gifted they are.’

Fifteen per cent of Warne’s Test wickets were the result of stumpings or catches behind, including 49 to Healy.

Other notable wrist spinners from Arthur Mailey and Clarrie Grimmett through to Bill O’Reilly and Richie Benaud all had a great reliance on their wicketkeepers. As good as they all were, none possessed Warne’s sublime talent and extraordinary accuracy.

The Healy-Warne combo tended to strike twice every three games. Healy’s successor Adam Gilchrist was to share in 59 dismissals with a percentage closer to one a match. Like Healy, he was a world record holder, whose wicketkeeping abilities were often underrated because of the majesty and power of his batting.

Even though Gilchrist’s percentages were superior, Healy was rated the more-rounded gloveman, especially the skills he displayed standing up. He loved Warne’s array of leg-spinners, flippers, sliders and zootas. Sometimes he’d even bowl a traditional googly – just to show he had one. In Bermuda one afternoon, one of the locals was floundering with Warne’s variety and whispered to Healy: ‘This bloke’s a lot easier to read on spin vision!’

Warne loved it when batsmen would engage with him and return some of his banter. In Sydney in 1994, South African tailender Pat Symcox kept padding Warne away.

‘You’ll never get through there, boy!’ he called.

Warne paused at the top of his approach, smiled, and continuing around the wicket, sent a leg-break in between Symcox’s legs which struck his middle and leg stumps. ‘People watching the dismissal on television couldn’t understand why the boys celebrated as if we had just dismissed Brian Lara for a duck,’ said Healy.

Healy kept to Warne for his first 1440 overs and 3450 overs overall in international cricket and said he could pick each of his deliveries in his sleep. Yet when he batted against Warne in a Sheffield Shield match in Melbourne in the mid-1990s, he wondered how he could possibly score, before Warne lobbed some higher-than-normal leggies which Healy was able to hit over the infield. It reinforced to Healy just how menacing Warne was, especially when it counted most.

Two of Healy’s all-time favourite dismissals were from Warne’s bowling, both in 1993 when he established himself as the leading slow bowler in the world.

‘We went to New Zealand before England and Shane hardly bowled a loose one, even in the nets, all tour,’ he said. ‘He was getting some extraordinary side spin and at Christchurch late in the first Test, he pitched one so far outside Ken Rutherford’s leg stump that I was unsighted. It bit and bounced and he nicked it and I managed to hang onto it. Kenny had made a 100 and that was a big wicket for us. [Australia won by an innings.]

‘The other one was a stumping from Graham Thorpe at Edgbaston [in the fifth Test]. He’d made 60 or so and they were fighting to save the game. He charged at him, it bounced and spun, one of Shane’s classic leg-breaks, and he was stranded. He was their last recognised batsman and we were able to go on and win by eight or nine wickets, our fourth win in five. You don’t forget moments like that.’

One delivery, however, still haunts Healy, a difficult, low-down stumping chance at Karachi in 1994 which went for the winning four byes as Inzamam-el-Haq and Mushtaq Ahmed added 57 in eight overs, the highest last-wicket partnership to win a Test match.

Having already taken eight wickets in the game, Warne bowled a leg-break pitching outside leg stump. Inzamam initially thought he could lift it to the vacant deep mid-wicket before changing his mind in mid-stroke and missing it completely. He thought he’d been bowled. So did Healy and, momentarily distracted, he lost focus and the ball scuttled through low, just missing the off stump and Healy’s gloves.

‘How I would have loved to have made that stumping,’ Healy said. ‘It was a chance a career could have been built on.’ It was a blimp – a big one at the time as Australia had never before won at Karachi. Healy kicked the stumps down in his frustration. Even the champions are human.

BRADMAN’S BEST

It wasn’t Ponsford, McCabe, Barnes or Morris: the greatest partner in Sir Donald Bradman’s life was his wife of 65 years, Lady Jessie Bradman.

The pair were inseparable, Bradman writing of the ‘comfort and encouragement’ and ‘sound judgement and counsel’ he received from his wife. ‘I would never have achieved what I achieved without Jessie,’ he said.

They first met in 1921, when Jessie Menzies, the daughter of a Glenquarry dairy farmer, came to board with the Bradmans during her first year of secondary school. She and the young Don would walk together across the local oval to school, Bradman carrying her books. She was 15 months younger than the Don. For him it was ‘love at first sight’.

‘I well remember the day [we met] as I’d been sent down the street to buy some groceries,’ Bradman said in an interview with Channel Nine’s Ray Martin in the mid-1990s. ‘I ran into the doctor’s car on my bike and had an accident. He had to take me home. My nose was all cut and there were scratches all over my face. And when I got home she [Jessie] was there at the door, having just been delivered by her father. She was going to stay with us and go to school [in Bowral] for 12 months. And we went to school every day for the rest of the year. That was when I fell in love with her, that very first day… [but] I don’t think she fell in love with me until much later because I was a terrible sight the day she saw me!’

Jessie was a grand beauty with wavy auburn hair and deep blue eyes. She was warm, outgoing and intelligent.

Bradman had wanted to become engaged on the eve of the 1930 Ashes tour of England but Jessie told Don he should go to England with his cricket as a free man and see if he felt the same way about her on his return. Their engagement was formalised in 1931. Six months later they were married and enjoyed an extended honeymoon in the USA and Canada where Bradman was the star attraction in a private tour arranged by the ex-Australian leg-spinner Arthur Mailey.

Fifty-two games were scheduled, Bradman playing all but two. After his epic Ashes summer of 1930, he was a magnetic drawcard everywhere. Americans used to seeing the hulking figure of baseball hero Babe Ruth marvelled at the Don’s slender frame and wondered how he could ‘whack ’em’ so far. On his way to amassing almost 4000 runs at an average of 99.45, Bradman notched 18 centuries including a highest score of 260 on a matting pitch laid over turf at the Ontario Reformatory in Guelph, the highest score ever made in Canada. He also took 24 wickets including six wickets in one eight-ball over against a Vancouver XV at Mt Tomie in Victoria. The team visited Yankee Stadium where Bradman met the Babe and other baseball legends. They also were shown around Hollywood and introduced to leading screen actors and actresses including Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, Mary Astor and Myrna Loy. On Broadway, the young honeymooners saw Paul Robeson sing his stirring ‘Ol’ Man River’ from the hit musical Showboat. It remained one of their all-time favourites.

With the Great Depression biting, the Bradmans moved to Adelaide, the prospect of a regular job with stockbroker and local cricket administrator Harry Hodgetts an irresistible lure in tough times. Cricket was only a leisure activity. Even record breakers needed to have Monday-to-Friday employment.

When Bradman became critically ill with peritonitis at the conclusion of the 1934 Ashes tour, Jessie took a train from Sydney to Melbourne and on to Perth to meet the Maloja, which was sailing to London. Reports circulated that Bradman had died, but Jessie continued her journey having telephoned the London hospital and being told her husband, while seriously ill, was still very much alive thanks to the expertise of the Australian surgeon Sir Douglas Shields. Peritonitis was a very serious and often fatal condition in those days before sulfa drugs and penicillin were available.

The Maloja arrived in London the day before Bradman was released, and the couple spent time in Scotland, London and the south of France before arriving back in Australia in early 1935.

The first of their three children, Ross, was to die within 48 hours of his birth in October 1936. Another son, John, was born in 1939 and daughter, Shirley, in 1941. Both had health issues and challenges. When John, a promising athlete, contracted polio in 1951 and spent most of the year in a steel frame, Bradman temporarily resigned all of his cricket administrative roles to share the caring duties with Jessie. At the launch of my Boys’ Own centenary book, Our Don Bradman, honouring Bradman in 2008, John said the months his Dad spent at home were among the happiest of his life.

While John was to make a full recovery and play first-grade cricket at Kensington, his father’s old club, he found the glare of being Don Bradman’s son so stifling that he was to change his name to Bradsen. Jessie was heartbroken. John reverted back to the Bradman name only months before his father’s death.

The Bradmans had built a two-storey brick house in Holden Street, Kensington Park, soon after their arrival in Adelaide and were to live there for the rest of their lives.

Jessie was not only a wife and a mother, she helped Bradman write some of his speeches and worked part-time as a bookkeeper when he was establishing his stockbroking business, Don Bradman and Co. During the Second World War, when Bradman was discharged with fibrositis, she nursed him and even shaved him.

Jessie was also instrumental in Bradman returning to cricket for the 1946–47 Ashes summer, saying to her husband it would be a pity if young John never got to see him play.

The Don’s passion for cricket saw him involved in numerous committees at both state and national level and cricket meetings took him away from home two and three nights a week for 30 years. After his extraordinary contributions on and off the field, he was to retreat from public view, refusing all interviews, until the mid-1990s when Channel Nine paid a seven-figure sum towards the Bradman Museum in Bowral, opening the door for the Don’s last major public interview.

Previously Jessie had often been pivotal in the Don agreeing to speak to journalists. Melbourne Herald photographer Ken Rainsbury famously captured the Don in his pyjamas and robe sipping a cup of tea one morning in Melbourne while he was still chairman of the Australian Cricket Board. The Don hadn’t been keen to do the interview, until Jessie persuaded him.

For some, she was the ultimate cricket widow, but the pair were extraordinarily close. On her death from cancer in 1997, Bradman said he’d never known an Adelaide winter to be so cold. He never truly recovered from her passing. His partnership with Jessie was by far the best of his life. She was the finest woman he ever met.