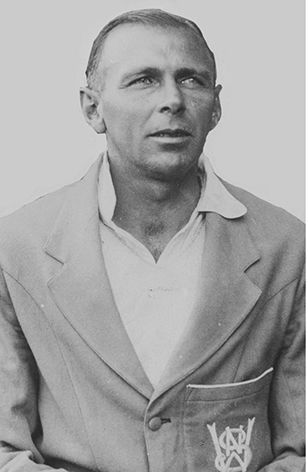

‘Gelignite Jack’: Three-in-one cricketer Jack Gregory from Sydney formed one of Australia’s mightiest Ashes new ball combinations with the Tasmanian-born EA ‘Ted’ McDonald.

E

‘Australia’s manager Steve Bernard put a stop to anyone getting naked in public, saying the team was in Muslim country…’

AN EXTRAORDINARY FAREWELL

Like most fast bowlers, Jason Gillespie always fancied his batting. His philosophy was simple: block the straight ones and attack anything wide. Trouble was, he was only averaging 12. In a team of champions he was required to bowl, not bat.

There was genuine delight when he broke through for an against-the-odds maiden Test half-century in his seventy-seventh innings against New Zealand in Brisbane in 2004–05 and celebrated by riding his cricket bat down the wicket à la Adam Sandler in Happy Gilmore.

Rarely did he ever bat higher than No. 10, but occasional nightwatchman opportunities arose, including one extraordinary time against Bangladesh at Chittagong in 2005–06 when he was elevated to No. 3 after the late dismissal of Matthew Hayden.

In the most unlikely of partnerships, Gillespie and the more-rated Mike Hussey shared a remarkable stand of 320 in what proved to be a farewell to remember for the tall South Australian, who for years had formed a mega bowling partnership with Glenn McGrath.

Gillespie’s share was a career-best 201 not out!

‘I’d never got a 100 before in any form of cricket, so to make one and then turn it into two was something beyond all comprehension,’ he said.

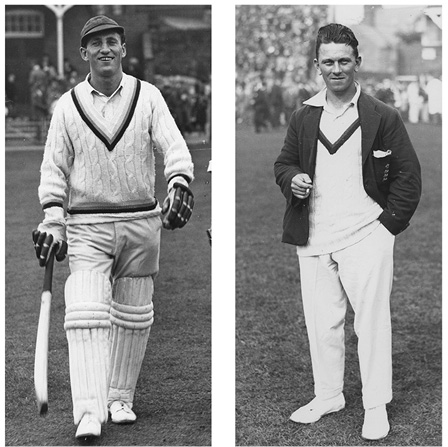

One-off wonders: Len Hutton (left) and Maurice Leyland only ever batted once together, adding 380 against Australia at The Oval in 1938.

|

ONE-OFF ‘SUPER’ PARTNERSHIPS* |

||

|

382 |

Len Hutton and Maurice Leyland (England) |

v Australia, The Oval, 1938 |

|

320 |

Jason Gillespie and Mike Hussey (Australia) |

v Bangladesh, Chittagong, 2005–06 |

|

245 |

Frank Woolley and Bob Wyatt (England) |

v South Africa, Old Trafford, 1929 |

|

243 |

Clem Hill and Roger Hartigan (Australia) |

v England, Adelaide Oval, 1907–08 |

|

233 |

Paul Sheahan and John Benaud (Australia) |

v Pakistan, Melbourne, 1972–73 |

|

207 |

HJH ‘Tup’ Scott and Billy Murdoch (Australia) |

v England, The Oval, 1884 |

|

206 |

Dave Nourse and Charlie Frank (South Africa) |

v Australia, Johannesburg, 1921–22 |

|

Other Australian one-off stands of note: |

||

|

198 |

Doug Walters and Peter Burge |

v England, Melbourne, 1965–66 |

|

185 |

Graham Yallop and Greg Matthews |

v Pakistan, Melbourne, 1983–84 |

|

* The largest partnerships between batsmen who only ever had one partnership in Tests |

||

Having batted through the second day on a wicket he rated as an absolute ‘road’, he was having a massage afterwards when the Australian physiotherapist Lucy Frostick suggested how good it would be if he could go on and make 200. Gillespie scoffed at the idea and said if he did that he’d celebrate by running around the oval nude.

Having only just won the opening Test of the series, the Australians were dominating the second. The Bangladeshi bowling and the fielding fell away dramatically as the Gillespie-Hussey partnership prospered. Finding himself in the 170s, Gillespie momentarily lost concentration and played a poor shot, earning an immediate rebuke from Hussey.

‘Huss urged me not to throw it away and said I’d never ever get another opportunity to make a Test double ton,’ said Gillespie, ‘so I put my head down again and pushed on.’

Having tucked a single around the corner for his double-century, he raised his bat in triumph, the wide smiles in the Australian dressing room reflecting one of the most bizarre feats of all.

Australia’s manager Steve Bernard put a stop to anyone getting naked in public, saying the team was in a Muslim country and should obey local protocol. Gillespie kept his clobber on. It was some farewell Test.

STATS FACT: Gillespie and Pakistan’s Wasim Akram are the only two batsmen to have a top score more than 10 times their career batting average.

ELEVEN MONTHS OF MAYHEM

Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald reigned together for less than a calendar year but struck as much apprehension into the minds of batsmen of the early 1920s as post-war expresses Lindwall and Miller and 1970s ‘demons’ Lillee and Thomson.

‘They were the sternest challenges to manhood,’ said historian David Frith.

|

JACK GREGORY and TED McDONALD TOGETHER |

|||||

|

|

Matches |

Wickets |

Average |

BB |

5wI |

|

1920–21 (in Australia) |

|||||

|

Jack Gregory |

5 |

23 |

24.17 |

7–69 |

1 |

|

Ted McDonald |

3 |

6 |

65.33 |

2–95 |

– |

|

1921 (England) |

|||||

|

Jack Gregory |

5 |

19 |

29.05 |

6–58 |

1 |

|

Ted McDonald |

5 |

27 |

24.74 |

5–32 |

2 |

|

1921–22 (South Africa) |

|||||

|

Jack Gregory |

3 |

15 |

18.93 |

6–77 |

1 |

|

Ted McDonald |

3 |

10 |

37.10 |

3–53 |

– |

With his bounding 15-yard run, kangaroo leap and intimidating pace, ‘Gelignite Jack’ Gregory made batsmen dance when they didn’t want to, backing his express bowling with cavalier batting and brilliant slips fielding.

Ted McDonald complemented him perfectly with his remarkable stamina, silky-smooth approach – which was longer than Gregory’s – deadly command of line and length and a breakback so vicious that it often bowled the unaware shouldering arms.

In the 11 Tests they played together immediately after World War I, Australia won seven and drew four, the pair amassing 100 wickets at an average of nine a match.

They claimed five or more wickets in an innings on five occasions, England playing all 16 of its tourists against them in 1920–21 and a record 30 in the five home Tests of 1921.

Gregory’s violent pace was responsible for more direct hits on English batsmen than any Australian in the first 75 years of Test cricket. In 1921 at Trent Bridge, Gregory struck debutant Ernest Tyldesley on the side of the face, the batsman all but passing out as the ball was breaking his wicket. At Lord’s, Gregory collected Frank Woolley on the back and the wrist just as he’d come in, and at Old Trafford, hit Phil Mead on the shoulder. All up, Gregory was responsible for 20 ‘hits’ on Englishmen, not that far behind the record of menacing Bodyliner Harold Larwood, with 33 hits on Australians, including two dozen in 1932–33.

Gregory had caused a sensation in the 1919 English season, taking more than 100 wickets and making almost 1000 runs for the Australian Imperial Forces team, despite having played only down the grades back home in Sydney. He said ‘the family name’ had triggered his initial Services team selection ahead of others. A right-arm fast bowler and a left-handed batsman educated at Shore school, he was the pivotal force in Australia building its unprecedented record of eight Ashes wins in a row.

His opening partner at the start of that record run in 1920–21 was the more leisurely paced Sydney-sider Charles Kelleway, before journeyman McDonald was included in the New Year of 1921, having taken nine wickets for Victoria against South Australia, eight either bowled or caught by wicketkeeper Jack Ellis. His returns in his opening Tests were modest, but in 1921, he stepped up and bowled at a sharp pace, his line perfect and his bouncer a genuine weapon, as Tyldesley found at The Oval when struck on the neck, one of McDonald’s six ‘direct hits’ in Ashes matches.

The pair created havoc all summer and mowed through English county and representative teams, amassing 270 wickets between them: McDonald 150 at 15.97 and Gregory 120 at 16.53.

‘He [McDonald] is that greatest asset any team can have,’ said Wisden, ‘a bowler difficult to play on the most perfect wickets.’ When the wickets were in favour of bowlers as they were at Liverpool, he took eight Lancastrian wickets for 62 and 10 for the match in a rain-ruined draw.

Originally from Launceston, McDonald had first represented Tasmania just a month after his nineteenth birthday and moved to the mainland to enhance both his cricket and football careers. Before playing his first Tests for Australia, aged 30, he appeared in a premiership team for Fitzroy.

His success in England led to a Lancashire League contract and regular county cricket with Lancashire, where he became one of the ultimate champions of the game. Gregory continued to harass and hurry batsmen until the opening Ashes Test of 1928–29, when he broke down with a knee injury and declared: ‘That’s it.’