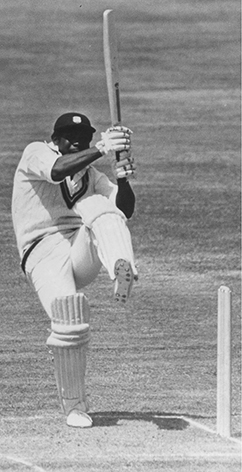

Ferocious: Gordon Greenidge was the aggressor in a magnificent opening combine with fellow Bajan Desmond Haynes. Patrick Eagar

I

‘Haynes told him he should be back in school, before yelling back up the wicket in deep West Indian: “KILL HIM BISHY’’.’

IN A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN

The tiny pear-shaped island of Barbados has long been Caribbean cricket’s Shangri-La. There are more turf wickets per square metre in Barbados than anywhere else in the world. Vacant street corners will have a goat or two grazing, plus a 22-yard wicket.

It is extraordinary that an island easily circumnavigated in half a day has been so cricket-rich. Of the West Indies’ first 200 Test cricketers, 25 per cent were from Barbados. Among them were the game’s outstanding all-rounder Garry Sobers; the Three W’s Everton Weekes, Frank Worrell and Clyde Walcott; pacemen Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Malcolm Marshall and Joel Garner; and opening batting supremos Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes.

It was in this elite cricketing environment that Greenidge, from Black Bess, and Haynes, from tough-as Holder’s Hill, were first introduced to the game. Like most cricket-mad Bajan kids, they played from dawn to dusk most months of the year on sun-drenched vacant fields, roads and beaches, developing an eagle-eye and a sure confidence so characteristic of their play at international grounds around the world.

‘We used to brag and say if you wanted to learn cricket, come into Holder’s Hill,’ said Haynes. ‘We not only played, we talked about it. As a young boy I could listen and hear all sorts of stories and learn.’

Greenidge joined his mother in England from his early teens, beginning his apprenticeship with the assistance of John Arlott at Hampshire before returning to Barbados where he was to become an integral part of one of the great all-time teams which ruled the cricket world for 15 years.

Greenidge hooked up with Haynes from 1978, the pair becoming the most enduring, prolific and intimidating in the history of Test cricket, opening a record 148 times and amassing almost 6500 runs at an average only a touch below 50. Ten of their 16 century stands came on home wickets in the Caribbean, where they averaged 65 and were truly in a league of their own.

‘They were an opening bowler’s nightmare come true,’ said long-time opponent, Australian Geoff Lawson. ‘Both had superb defensive techniques that had them well equipped to keep out the best you could serve up. After repelling the early stuff, they would carry the attack to the bowlers. Most of your energy would then be spent trying to save runs.’

Their longevity was extraordinary, and over their 13 years and 89 Tests at the head of the order, the West Indies won 48 and lost only eight games. No team had a higher quality battery of fast bowlers to rank with the seemingly endless line of the Caribbean’s flamethrowers, but with Greenidge and Haynes at the head of the order and King Viv in at three, they invariably had lots of runs to play with.

From being out-and-out dashers, Greenidge and Haynes learned to temper their aggression – but not always their volatility. They were invariably among the most ‘chatty’ of the West Indian short catchers. Haynes at short leg was always keen to remind a new batsman of the physical danger confronting him. As a wide-eyed first-gamer, Justin Langer was taking guard against Ian Bishop in Adelaide in 1992–93. Haynes told him he should be back in school, before yelling back up the wicket in deep West Indian: ‘KILL HIM BISHY.’

Despite his wide, engaging smile, Haynes could be easily upset – and confrontational. In 1984, as the Windies rolled to an easy win against Kim Hughes’ Australians in Brisbane, he was dismissed by the hard-line Lawson and took umbrage at the throwaway line ‘On ya bike champ’ (or something like that).

As he was walking off he turned and, using his bat like a gun, pointed it straight at Lawson and ‘fired’. The game ended within minutes and a still-angry Haynes grabbed a stump and went to charge into the Australian room only to be held back by teammates. I was in a corner chatting with Michael Holding at the time. He just shook his head.

‘Greenidge and Haynes didn’t always appreciate having their arrogance thrown back in their faces,’ said Lawson in explanation, ‘and often reacted childishly.’

In 1991 when Australian wicketkeeper Ian Healy claimed a low catch Haynes felt had bounced at his home ground Kensington Oval, Haynes called him a cheat, triggering more on-field drama. An incensed Healy told Haynes to ‘let the effing umpire do his effing job’. Haynes responded by inviting Healy to meet him after the game. It was distasteful and unnecessary.

Greenidge was five years Haynes’ senior and given his experience of playing county cricket in England and opening up with the fabled South African Barry Richards, he was a father figure for Haynes and many of the other younger West Indians, quietly offering advice and encouragement when asked.

In Haynes he recognised a young, committed, very emotional champion in the making. He had rough edges, but he also possessed a rare drive to improve and hated it when he felt he’d let the team down.

‘Even if I got our first,’ said Greenidge, ‘he’d be the one who screamed, threw tantrums, just trying to release that sense of disappointment and frustration.’

Greenidge had overcome a pair on debut against the Australians in 1975–76 to become one of world cricket’s most complete batsmen, equally at home against the pace as he was against the spinners. He could be introverted, even sullen. Haynes was more flamboyant. The gold chain around his neck summed up his attitude to life: ‘Live, Love, Laugh’.

As running partners they had a fine understanding and were involved in only four run-outs in their 148 innings. They’d regularly run singles with just a nod of the head, rather than a call. Haynes became used to senior pro Greenidge farming the strike by taking a single from the last ball of an over.

‘The better his form was, the more eager he was to get the strike, the further he backed up. “Let me get the strike man,” he would say to me,’ said Haynes. ‘So I played second fiddle. I fed him. I knew if someone was going to be dropped, it wasn’t going to be him. There was a greater onus on me to maintain the partnership. Just watching him from the other end was a lesson. I was perfectly happy and proud to be second fiddle to him.’

They built an air of impregnability from the time they started with 87 in the opening Test against Jeff Thomson and the 1978 Australians at Port-of-Spain. A fortnight later they shared their first century stand, 131, in front of an adoring home crowd at Kensington Oval, Bridgetown. Included were sixteen 4s and three 6s.

‘They worked as a wonderful partnership… rarely was there a dull moment,’ said Bruce Yardley, who opposed them in that 1978 series. ‘They applied the basics of cricket, defended the good stuff, and boy, didn’t they attack anything they fancied!’

Haynes’ whirlwind maiden Test knocks of 61, 66 and 55 against the Australians earned him the nickname of ‘Hammer’ Haynes. A great entertainer, he was rarely out of form for too long.

Their golden period came in the early to mid-1980s when, in the space of 30 Tests, they amassed two 250-run opening stands, the highpoints in five century stands. Additionally, they were responsible for 16 half-century starts.

At St John’s in 1990, they began with a career-best 298 against England, Greenidge in his one hundredth Test making 149 and Haynes 167, the Windies winning by an innings.

They established record stands against four countries: England, Australia, New Zealand and India. In eight series they averaged 50 or more and in 1983–84 against the Australians, their average ballooned to 136. The partnerships that golden summer were: 29 and 250 unfinished (Georgetown), 35 (Port-of-Spain), 132 and 21 unfinished (Bridgetown), 0 (St John’s) and 162 and 55 unfinished (Kingston). Greenidge averaged 78 and Haynes 93, the Windies winning 3–0.

|

Greenidge and Haynes’S 100-RUN TEST STANDS |

|

|

298 |

v England, St John’s, 1989–90 |

|

296* |

v Australia, St John’s, 1983–84 |

|

296 |

v India, St John’s, 1982–83 |

|

250* |

v Australia, Georgetown, 1983–84 |

|

225 |

v New Zealand, Christchurch, 1980 |

|

168 |

v England Port-of-Spain, 1980–81 |

|

162 |

v Australia, Kingston, 1983–84 |

|

150 |

v New Zealand, Wellington, 1986–87 |

|

135 |

v Australia, Brisbane 1988–89 |

|

132 |

v Australia, Bridgetown, 1983–84 |

|

131 |

v Australia, Bridgetown, 1977–78 |

|

129 |

v Australia, Bridgetown, 1990–91 |

|

118 |

v Australia, Kingston, 1990–91 |

|

116 |

v England, Kingston, 1981–82 |

|

114 |

v India, Calcutta, 1987–88 |

|

106 |

v England, Leeds, 1984 |

|

* unfinished |

|

The pair ‘played for each other’, said long-time teammate Courtney Walsh. ‘When they were both in their prime, to watch them was to see perfection in the science of opening an innings,’ he said.

Greenidge struck the ball straight with such brutal power that at practice the West Indian fast bowlers dared not turn their backs on him as they walked back to the top of their marks. Viv Richards was the only other player accorded similar respect.

Australian fast bowler Rodney Hogg reckoned you almost needed to bowl in a helmet, as Greenidge smoked his on-the-up drives straight back up the wicket. Even when Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson were at their fieriest, Greenidge would belligerently launch onto the front foot, looking to power the ball straight through the covers. If it was short, he’d pull and cut with equal savagery. He had massive biceps and forearms. Like Everton Weekes, when he hit a ball, it stayed hit, even with the wafer-thin bats then in use.

With his English experience, he was technically tighter than Haynes and often just as dangerous when he was limping as when he seemed to be 100 per cent fit.

Haynes was a wonderfully rhythmic stroke-maker who learnt to convert his starts into bigger scores. A deep thinker, he opened his stance in mid-career with considerable success. Few played Dennis Lillee with as much assurance – or were as consistently combative, one of the offshoots of coming from the highly competitive atmosphere of cricket at Holder’s Hill.

‘He always had the drive to succeed,’ said Greenidge, ‘but it took time for him to build up the technical side of his game. The mental capacity was always there, it was just a matter of bringing it out. I could not have asked for a better partner. He kept going, kept growing, not just in batting terms but also in his all-round cricketing knowledge.’

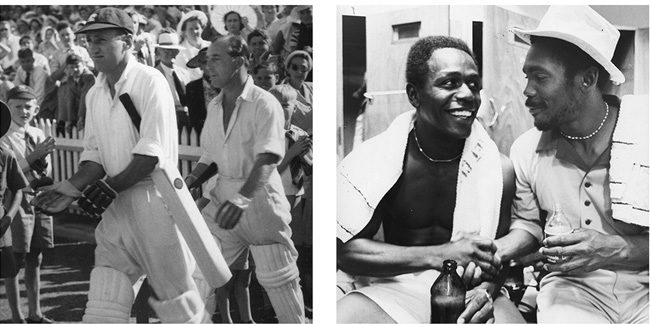

Left: Spanning Sixteen Years: Ashes openers Len Hutton (left) with Bill Edrich. They opened first in 1938 and for the last time in 1954–55.

Right: Barbados Masters: Desmond Haynes (left) with fellow Bajan Gordon Greenidge. They brutalised opposing attacks.

Greenidge and Haynes were also masters of the one-day game and together they were the first to 15 ODI century stands and remain among the few limited-over pairs to have averaged 50 or more. With their trademark aggression the Windies would invariably score their first 60 runs at four an over, setting the scene for King Viv, Richie Richardson and co., and this in an era before the advent of Twenty20 cricket, big bats and shorter boundaries.

On his West Indian debut against the 1978 Australians, Haynes slammed a memorable 148 from 136 balls, the first of his 17 ODI centuries.

‘It was a one-dayer at Antigua,’ said Yardley. ‘Roy Fredericks had retired and Dessie tore our attack apart, including “Two-up” [Jeff Thomson]. Dessie actually went down on one knee and cover drove him for four. [Captain] Bob Simpson played as our spinner that day and Dessie propped forward, rocked back and off the back foot and put it over long on, into the street. “Holy smoke,” we wondered, “Who is this guy?”

‘And Gordon smacked them even harder. In Sydney in 1982, “DK” [Lillee] bowled a bouncer and Gordon absolutely smashed it into the square leg fence. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a ball hit harder. I wondered when DK would test him again but he made him wait for several overs. It was shrewd and brilliant. Having bowled a series of good length deliveries, giving Gordon no room to swing, Dennis sensed the moment and bowled one shorter and faster. Gordon was seeing it like a watermelon but this one was onto him quicker, he got the pull shot high on the bat and “Stumpy” [Bruce Laird] racing in from mid-on, took an amazing diving catch at the bowler’s end stumps. It was some contest whenever those two were opposed.

|

MOST PARTNERSHIPS IN TESTS |

|

|

148 |

Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes (West Indies) |

|

143 |

Rahul Dravid and Sachin Tendulkar (India) |

|

122 |

Justin Langer and Matthew Hayden (Australia) Marvan Atapattu and Sanath Jayasuriya (Sri Lanka) |

|

117 |

Andrew Strauss and Alastair Cook (England) |

|

95 |

Mahela Jayawardene and Kumar Sangakkara (Sri Lanka) |

|

88 |

Alec Stewart and Mike Atherton (England) |

|

85 |

David Boon and Mark Taylor (Australia) Rahul Dravid and VVS Laxman (India) |

|

Other Australian pairs: |

|

|

78 |

Mark Taylor and Michael Slater |

|

76 |

Matthew Hayden and Ricky Ponting |

|

73 |

Mark Waugh and Steve Waugh |

|

64 |

Bobby Simpson and Bill Lawry |

|

61 |

Steve Waugh and Ian Healy |

|

THEY OPENED IN TESTS SPANNING 10 YEARS and MORE |

|||

|

Span in years |

|

Innings |

Last Test |

|

16 |

Len Hutton and Bill Edrich (England) |

10 |

1954–55 |

|

13 |

Bruce Mitchell and Eric Rowan (South Africa) |

6 |

1948–49 |

|

13 |

Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes (WI) |

148 |

1990–91 |

|

Span in years |

|

Innings |

Last Test |

|

11 |

Jack Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes (England) |

36 |

1920–21 |

|

10 |

Sid Gregory and Victor Trumper (Australia) |

3 |

1911–12 |

|

10 |

Charles Macartney and Warren Bardsley (Australia) |

2 |

1921 |

|

10 |

Mushtaq Ali and Vijay Merchant (India) |

7 |

1946 |

|

10 |

Marvan Atapattu and Sanath Jayasuriya (Sri Lanka) |

118 |

2007–08 |

|

Other Australian pairs: |

|||

|

7 |

Bill Ponsford and Bill Woodfull |

22 |

1934 |

|

7 |

Michael Slater and Matthew Hayden |

25 |

2001 |

|

6 |

Bobby Simpson and Bill Lawry |

62 |

1967–68 |

|

6 |

Andrew Hilditch and Graeme Wood |

18 |

1985 |

|

5 |

Mark Taylor and Michael Slater |

78 |

1998–99 |

|

5 |

Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer |

113 |

2006–07 |

INSPIRED

On song, they were as inspired and exhilarating as any Australian pair and often reserved their best for the most pivotal moments.

Bars emptied when Norman O’Neill and Neil Harvey were in occupation in the late 1950s and early 1960s. No one wanted to miss a ball, so joyous and effortless was their strokeplay.

Five times they shared century stands in Tests – and often when runs were at a premium and high-profiled teammates out cheaply.

On a spinner’s wicket against the West Indians in Sydney in 1960–61, they added 108 in even time before Harvey hurt his leg, halting Australia’s advance on the final morning.

Their highest and most important partnership was their 207 out of 387 in ferocious heat at Bombay in 1959–60. Harvey was the in-form player in the world and delighted with his twinkling footwork and eagle eye. O’Neill’s driving was supreme and for almost five hours he and Harvey defied the Indians, Harvey scoring 102 and O’Neill 163. No-one else made 40.

As he was leaving the dressing room, O’Neill was stopped by captain Richie Benaud. ‘You are one of the best players in the world. Go out and thrash ’em.’

The Indians bowled immaculate lines, their left-arm spinner Bapu Nadkarni defying the heat to deliver more than 50 overs.

Hour after hour the pair batted, defying the bowling and the firecrackers which were part of the general commotion, even when bowlers were about to deliver.

As was the Indian custom, on reaching their hundreds, they each received a garland of flowers and a handful of lemons from fans who jumped the fence and ran onto the pitch.

In their last stand together, against Ted Dexter’s 1962–63 Englishmen in Adelaide, they added 194 in less than three hours against the might of Trueman, Statham and co.

As Test partners, they averaged 70 together, their displays truly majestic, as if each was inspired by the other.

Harvey was almost 10 years older than O’Neill – not that it showed. Even into his 30s, he would scamper up and down the wicket like a teenager and it wasn’t until his final Ashes summer in 1962–63 that he vacated the No. 3 position in favour of his gifted New South Wales teammate.