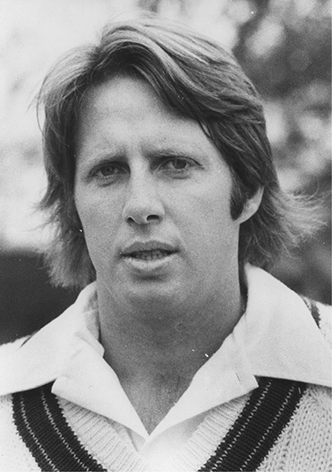

Tearaway: The fastest bowler in history, Jeff Thomson. He didn’t know where they were going… neither did the batsmen. In back-to-back summers in the 1970s, ‘Thommo’ and fellow express Dennis Lillee ruled like no Australian pair before or since.

L

‘The rebuff left old Bert broken-hearted. He may have lacked the social graces of some and his action may not have been as pure as Blackie’s, but he’d never been no-balled for throwing…’

LAST CHANCE HERO

Danny Morrison held the world record of 24 ducks in 47 Tests coming into the opening Test of the 1996–97 New Zealand summer against England at Eden Park. The Kiwis were facing certain outright defeat at 9–142 – an overall lead of just 11 – early in the final afternoon. Back in the rooms, New Zealand captain Lee Germon was rehearsing his loser’s speech.

Nathan Astle was still not out, but one of England’s pacemen, Dom Cork, Alan Mullally or Darren Gough, only had to bowl wicket to wicket to dislodge Morrison… or so everyone thought.

One hundred and sixty-six minutes later, Morrison was still there, unconquered, having helped Astle to one of the great fighting centuries and New Zealand to the unlikeliest of draws.

‘Let’s just enjoy it,’ Astle had said to Morrison when they came together shortly after 2 pm.

Morrison’s sole initial aim was to stay long enough to see Astle to 50. ‘I never dreamed I’d be there when he got his century,’ he said. His 14 not out, following his unbeaten 6 in the first innings, lifted his Test career average to 8. And that’s where it stayed. He never played another Test.

LIFE BEGINS AT 40

If it wasn’t for the generosity and contacts of the St Kilda Cricket Club’s livewire president RL ‘Doc’ Morton, Melbourne club cricket’s most famous bowling duo would never have been.

Don Blackie was working in the country for the local postal service and doing little more physical than tending his rose garden at weekends when Morton, his family’s doctor, arrived unannounced and invited him to once again play District cricket alongside one of his old Prahran teammates, Bert Cohen.

Fifteen years earlier, Blackie had played his one and only game for Victoria against a visiting team from Fiji. A tall off-spinner with a run-in from mid-off, a ramrod straight arm and ever-so-long fingers which encouraged spin on the flattest of surfaces, he’d rarely again challenged for higher honours despite being a four-time bowling average winner at Toorak Park.

Another mature-age recruit about to join the Seasiders was Bert Ironmonger, a left-arm finger spinner noted for his ability to consistently land a ball on a sixpence – despite having sliced off the top of his index finger in a farming accident as a child. He’d flick the ball off a corn on his shortened finger, imparting swing, seam and spin at close to medium pace. In the era of covered run-ups and uncovered wickets, he could be unplayable, especially when there was any extra juice in the wickets. He’d been the bowler of the Australian ‘B’ team tour to New Zealand just 18 months earlier, taking 10 wickets against Canterbury and 13 in the two representative matches against NZ.

Known as ‘Dainty’ because of his soft, economical run to the wicket, he’d been lured back to Melbourne after the failure of the latest of his business ventures, a hotel in inner Sydney. Within weeks of setting up a tobacconist’s shop just around the corner from St Kilda’s Junction Oval, he was mortified to arrive at work one morning to find it had been burgled. Little more than the shelving remained. Morton arranged an immediate cash hand-out for his family and organised Ironmonger a job mowing lawns with the local St Kilda council. Ironmonger thrived in his new Monday to Friday role, the extra fitness built from pushing hand mowers around the St Kilda parklands helping him to regularly bowl for marathon periods on the hottest of days and triggering his rise into Australia’s elite XI, including his final four Tests at the grand old age of 50. No Australian Test representative has been older.

Influential: St Kilda Cricket Club president Dr. R. L. Morton lured Don Blackie out of retirement and found a new job for Bert Ironmonger which triggered his Test promotion.

The two 40-year-olds were pivotal in St Kilda’s rise from the time they took 70 wickets in their first season together in 1922–23, Blackie playing from the opening game in October and Ironmonger, who’d begun the club season in Sydney, from November. The club’s first XI narrowly missed the finals before winning an unprecedented four flags on end. In all, Blackie and Ironmonger were together in six premierships in the 1920s and early 1930s, the pair regularly bowling through an innings, making a third and fourth bowler almost unnecessary.

In the club’s run of four premierships in a row in 1923–24, 1924–25, 1925–26 and 1926–27, they claimed 110 of the 138 wickets to fall to the bowlers. In six winning Grand Finals, Blackie took 38 wickets and Ironmonger 35. Seven other bowlers used in the play-offs took just 10 wickets between them, one of the little-used back-ups being a young ‘Chuck’ Fleetwood-Smith.

With record-breaking Bill Ponsford and Cohen dominating the batting, St Kilda could lay claim to being the champion club team in all Australasia.

It was extraordinary how often Blackie would find himself bowling against the opposition’s left-handers and Ironmonger the right-handers. They’d sit in the rooms, analysing the opposition’s best players, planning fielding positions and fine-tuning tactics.

Both were to bowl more than 20,000 balls and take 500-plus wickets for St Kilda, Ironmonger’s costing 13 runs apiece and Blackie 14. Between them they took five wickets or more in an innings 88 times, Ironmonger’s best eight for 37 in his first season and Blackie’s ten for 64 – eight of the 10 bowled or lbw! They took all 10 wickets to fall on 13 occasions.

|

THE OLD FIRM: SEASON BY SEASON AT ST KILDA DON BLACKIE |

||||||

|

Season |

Balls |

Runs |

Wickets |

Average |

BB |

5wI |

|

1922–23 |

1424 |

711 |

41 |

17.34 |

6–49 |

4 |

|

1923–24* |

1886 |

629 |

51 |

12.33 |

7–38 |

4 |

|

1924–25* |

1809 |

532 |

58 |

9.17 |

7–71 |

7 |

|

1925–26* |

2004 |

649 |

59 |

11.00 |

7–39 |

6 |

|

1926–27* |

2268 |

825 |

64 |

12.89 |

10–64 |

8 |

|

1927–28 |

1021 |

284 |

14 |

20.26 |

7–113 |

1 |

|

1928 Tas tour |

192 |

122 |

9 |

13.55 |

3–24 |

– |

|

1928–29 |

1553 |

491 |

29 |

16.93 |

5–30 |

3 |

|

1929–30 |

2228 |

738 |

42 |

17.61 |

5–35 |

4 |

|

1930–31 |

1331 |

520 |

30 |

17.33 |

6–26 |

2 |

|

1931–32* |

1075 |

453 |

29 |

15.62 |

7–34 |

1 |

|

1932–33 |

886 |

340 |

24 |

14.16 |

6–56 |

1 |

|

1933–34* |

2016 |

656 |

47 |

13.95 |

6–64 |

4 |

|

1934–35 |

668 |

219 |

7 |

31.28 |

2–14 |

– |

|

Total |

20,381 |

7169 |

504 |

14.22 |

10–64 |

45 |

|

BERT IRONMONGER |

||||||

|

Season |

Balls |

Runs |

Wickets |

Average |

BB |

5wI |

|

1922–23 |

1030 |

490 |

29 |

16.89 |

8–65 |

3 |

|

1923–24* |

1852 |

654 |

59 |

11.08 |

6–37 |

4 |

|

1924–25* |

1513 |

446 |

39 |

11.43 |

6–41 |

2 |

|

1925–26* |

2126 |

719 |

60 |

11.98 |

8–47 |

4 |

|

1926–27* |

2691 |

999 |

50 |

19.98 |

6–28 |

3 |

|

1927–28 |

1064 |

340 |

19 |

17.89 |

8–39 |

3 |

|

1928 Tas tour |

272 |

131 |

17 |

7.70 |

7–31 |

1 |

|

1928–29 |

1425 |

482 |

30 |

16.06 |

5–26 |

2 |

|

1929–30 |

2743 |

893 |

57 |

15.66 |

7–48 |

6 |

|

1930–31 |

1610 |

539 |

41 |

13.14 |

6–19 |

4 |

|

1931–32* |

1208 |

385 |

39 |

9.87 |

6–50 |

5 |

|

1932–33 |

1081 |

331 |

29 |

11.41 |

6–42 |

3 |

|

1933–34* |

1150 |

361 |

27 |

13.37 |

7–53 |

2 |

|

1934–35 |

930 |

245 |

23 |

10.65 |

5–25 |

1 |

|

Total |

20,695 |

7015 |

519 |

13.52 |

8–37 |

43 |

|

*premiership years Table: Ron Harbourd |

Blackie took 4 10wM and Ironmonger 5 10wM |

|||||

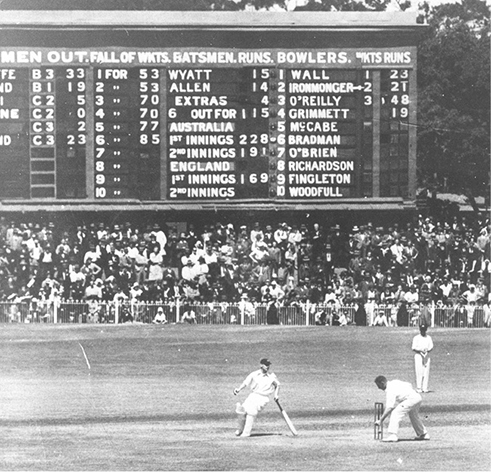

Bodyline Test: Fifty-year-old Bert Ironmonger attempts a run out during the Melbourne Test of 1932–33, the only one in the controversial series which Australia won.

Their success at St Kilda was rewarded at both Victorian and Australian level, Ironmonger playing 14 home Tests and Blackie three, including his first alongside Ironmonger in Sydney in 1928–29, the match in which a young Don Bradman served as twelfth man for the one and only time in his career.

The first time they’d teamed together at interstate level was in 1925–26 when they claimed all 10 first-innings wickets opening the bowling for Victoria against the visiting West Australians at Fitzroy, Ironmonger taking seven for 30, six bowled or lbw and Blackie three for 57. Their game haul was 13.

Ironmonger reaped damage at every level and was even called for as a substitute to bolster Australia’s 1934 Ashes party, only for the austere Australian Board of Control to overrule captain Bill Woodfull, saying Woodfull could pick anyone but the St Kilda veteran. Woodfull said if he couldn’t choose Ironmonger he didn’t want anyone else. The rebuff left old Bert broken-hearted. He may have lacked the social graces of some and his action may not have been as pure as Blackie’s, but he’d never been no-balled for throwing. At the time authorities were trying to rebuild calmer relations, the Australians not wanting to spark a throwing controversy so soon after the acrimonious Bodyline summer. It was known to them that PF ‘Plum’ Warner, England’s most powerful and most profiled ex-cricketer, had questioned Ironmonger’s action.

Ironmonger averaged more than five wickets per Test, 70 per cent of his 74 Test wickets coming in the top-order. Don Bradman regarded him as the best bowler never to be chosen for an Ashes campaign.

Within months Ironmonger had announced his intention to retire, playing a farewell club season at the Junction alongside Blackie in 1934–35 before being called into the unofficial Australian team which toured India and Ceylon under the captaincy of Frank Tarrant in 1935–36.

Blackie’s 14 Test wickets included a six-for at the MCG in the 1928–29 Christmas Test, his victims including double-centurion Walter Hammond. He retired in 1935, his hair silver but his action still bouncy. St Kilda named its pride and joy new grandstand, which still stands, in the pair’s honour.

They had one last game together in a patriotic fixture at the MCG in 1939 to aid the War Veterans Homes Trust fund.

Woodfull called them ‘The Old Firm’ and said they would always be one of the greatest bowling batteries in the history of the game. ‘They are masters of their art,’ he said.

LILLI’AN THOMSON… THE DEMOLITION MEN

It’s one of Australian cricket’s most immortal catch-cries: ‘Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust, if Lillee Don’t Get Ya, Thomson Must.’

Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson were the most menacing set of speedsters since Bodyliners Harold Larwood and Bill Voce. Furiously fast and volatile, they triggered an extraordinary Australian domination not seen since the days of Richie Benaud. In back-to-back Test summers in the mid-1970s, Australia won nine of 11 Tests against England and the West Indies, the two next-best teams in the world. England’s solitary success came when Thomson was absent and Lillee injured in the first hour in the final match in Melbourne.

As a Thomson thunderbolt thudded into the gloves of wicketkeeper Rod Marsh in his unforgettable Ashes debut in Brisbane in 1974–75, Marsh winced in pain and said to first-slipsman Ian Chappell, ‘Hell that hurt… but I love it.’

There was nowhere to run and nowhere to hide when Lillee and Thomson were threatening. Neither cared if they struck a batsman. If a tailender looked to outstay his welcome, he knew that he would soon be subjected to some ‘chin music’. Thomson was famously quoted as saying there was nothing better than seeing blood on the pitch. Lillee wanted to hit the batsmen under the rib cage so that ‘they were so hurt they didn’t want to face me any more’.

|

THE OLD FIRM: THEIR FINEST GRAND FINAL PERFORMANCES |

|

|

1924–25 |

All 20 wicketsBlackie 5–34 and 6–48, Ironmonger 5–27 and 4–30 |

|

1925–26 |

18 wicketsBlackie 5–21 and 4–24, Ironmonger 4–45 and 5–27 |

|

1931–32 |

17 wicketsBlackie 4–52 and 4–61, Ironmonger 5–24 and 4–49 |

In those two extraordinary summers, the most sensational since Bodyline, Lillee and Thomson changed the face of cricket forever. Having torn through the Englishmen 4–1, they humbled the West Indians 5–1. Windies’ captain Clive Lloyd vowed that no team in his charge from the Caribbean would ever again be so humiliated and immediately started stacking his teams with four fast bowlers. Spin was forever after an afterthought – and helmets a necessity in even the tailender’s kitbags.

In those two much-remembered Australian series of the mid-1970s, Lillee took 52 wickets and Thomson 62. They were positively lethal, Lillee downwind and ‘Thommo’ into it.

In Brisbane, captain Ian Chappell initially had intended to open the bowling with Lillee and the medium-paced Max Walker, thinking Thomson would be better suited following Lillee with the wind at his back. But after Lillee’s opening over, on the spur of the moment, he threw the ball to Thomson.

‘In the few overs that followed, I watched in awe,’ Chappell said. ‘Thommo was the fastest into-the-wind bowler I’d seen. I don’t think the Englishmen knew what had hit them… there was great joy amongst us all to see the fearful pace they generated.’

England had held the Ashes since 1970–71 but were literally blown away by the two frontline pacemen – plus seam specialist Walker who netted 23 wickets.

Lillee had been riled on the second morning in Brisbane when he was dismissed by a Tony Greig bouncer which saw him finish inelegantly on his backside, with keeper Alan Knott gloving a simple catch. He was spoiling for a fight and from his first over was furiously fast.

‘He also managed to make the ball leave the bat and bounce a lot,’ said opener Dennis Amiss. ‘Clearly I’d underestimated him.’

Amiss had averaged 75 in six home Tests in 1974 on his way to more than 1300 runs for the calendar year, yet was challenged like never before. His partner Brian Luckhurst, 36, was clearly intimidated and admitted it was one tour too many for him. Within weeks of the Tests starting he knew he shouldn’t have been there.

‘The Lillee-Thomson phenomenon was not pleasant,’ Luckhurst said. ‘It gave me an insight into how Test cricket was changing. To look at us walking out in those pre-helmet days to face two of the fastest and most dangerous bowlers the world has seen – on lightning-quick and bouncy surfaces – provides an almost ghoulish fascination.’

England’s opening stands that summer averaged just a shade above 30. Amiss had his thumb broken in England’s second innings in Brisbane, having been struck by both expressmen.

‘We were left with an awkward last hour [on the penultimate night] in which I faced the most frightening fast bowling I have ever seen,’ Amiss said.

‘Thomson and Lillee ran [in] like madmen. They were not bowling bouncers but deliveries which lifted unpredictably from just short of a length. Three of them whistled by my chin and because the [Brisbane] light was poor, one of the umpires warned Thomson to pitch the ball up. Thomson was clearly not having any. The next four balls whistled past my face and off we went [for bad light].’

Only two of England’s top-order, the warrior-like John Edrich and Greig, averaged 40 or more for the summer. David Lloyd, Amiss, veteran reinforcement Colin Cowdrey and Luckhurst were all sub-25.

‘It was better to be watching rather than batting that summer,’ said Lloyd. ‘When Lillee and Thomson got it right and the pitches gave them some help, as most did, they were an awesome pairing. Get through an over from one of them and there was not a moment of respite with the other one pawing the ground. We were still playing by the old Australian regulation of eight-ball overs and there were times when five of the eight were flying past nose or chest. We weren’t good enough to stem the onrushing tide.’

In Sydney on a greentop, the juiced-up crowd on the Hill began to chant ‘Kill… KILL… KILLLLL’ as Lillee and Thomson tore into the tourists. One Thomson bouncer sconed Keith Fletcher, whose head protection consisted of his MCC cap complete with its emblem of St George on his horse. As Fletcher collapsed, teammate Geoff Arnold jumped to his feet in the rooms and exclaimed: ‘Blimey, ee’s just knocked St George off ’is ’orse!’

Earlier in the game, Greig had struck Lillee on the point of the elbow, causing him to drop his bat in pain. He was unimpressed when Fletcher, fielding in the gully, asked: ‘Did it hurt?’ Fletcher had picked up Lillee’s bat but after Lillee’s stream of invective, tossed it back on the ground, leaving Lillee to retrieve it himself.

Having already forced Edrich to retire hurt with broken ribs, Lillee found an extra gear when he sighted the next-man-in, Fletcher, and began to pitch relentlessly short.

‘At least half a dozen times I flicked my head out of the way through sheer instinct as balls I had not seen at all whipped past the end of my nose,’ said Fletcher. ‘Some missed me by only a fraction of an inch.’ Of the searing Thomson lifter, which he failed to evade, Fletcher said he’d simply frozen, despite having ‘a reasonable sight of it’.

‘For some inexplicable reason, my reactions just didn’t work in time,’ he said. As he ducked, he got only the lightest of gloves onto the ball before it struck him directly on the skull.

Fletcher said he tired that summer of using his bat purely as a shield. One delivery from Thomson in Perth spat back at him late with such venom that he could only just cover his face with his gloves, the ball deflecting through to Marsh who took a juggling catch.

‘That ball was the quickest of my career,’ said Fletcher. ‘It convinced me that Thomson must rank alongside the quickest of all Test bowlers. I only just had time to get my gloves in front of my face. The deflection was travelling so fast it actually thumped the chest of Marsh standing more than 20 metres back before he got his gloves to it.’

In Perth, Lloyd had his box inverted by a Thomson screamer. After his dismissal he lay on the rubdown table, shaking involuntarily.

Forty-two-year-old Cowdrey said the sheer pace and unpredictability of the Lillee-Thomson combination made them the most difficult pair he’d ever opposed in his prime, including Lindwall and Miller, the West Indians Hall and Griffith, and the South African expresses Heine and Adcock.

Greg Chappell said Thomson often bowled at speeds in excess of 160 km/h (100 mph). ‘You can name anyone you like: Roberts, Holding, Marshall… Thommo was two yards quicker than them all. Before he did his shoulder he was frighteningly quick.’

Nineteen of their 26 Tests together were in Australia where they were at their most effective and lethal. Surprisingly, Lillee’s home ground of Perth was his weakest ground, where his wickets came at an average of 27.2. Perth was Thommo’s second weakest, his wickets also coming at 27.2.

Leading into his demolition of the English, Thomson had played only one Test, against Pakistan in Melbourne several years earlier, when he carried an injury into the game and failed to take a wicket.

‘We’d never even heard of him,’ said Lloyd. ‘He’d played one Test, a couple of years earlier, and taken nought for a hundred and plenty. Why would we waste time worrying about him?’

From mid-tour, at the suggestion of the team’s physiotherapist Bernard Thomas, most of the Englishmen strapped on made-to-measure foam rubber chest guards.

‘Never in my career have I witnessed so much protective gear applied to individuals before they went out to bat,’ said captain Mike Denness, who stood down for a Test in mid-series. ‘On the plane flying from Australia to New Zealand, the players were clearly relieved that they had left Australia intact and without fatal injury.’

Thomson’s Brisbane blitz inspired Lillee, who had played only grade cricket in Perth the previous summer as a specialist batsman while recuperating from a back breakdown.

Lillee had been genuinely surprised to make it past the first Test and in his early comeback Sheffield Shield matches with Western Australia, had despaired of ever bowling truly fast again, despite his exhaustive winter fitness campaign.

Buoyed by Thomson’s outstanding performances, the further the Test series went, the more confident and aggressive Lillee became. He stared, gesticulated and pointed at the English batsmen, going out of his way to be cranky and outrageous. He wanted a mid-pitch war.

In Sydney on the fastest wicket in the east, his first ball to Amiss soared over both the batsman and keeper Marsh and thudded one bounce into the sightscreen. ‘We were always ducking and weaving and not always successfully,’ said Amiss.

The English could use their own expressman Bob Willis sparingly in only very short spells because of his battle-scarred knees, and possessed no-one else who could engender the same heat as Lillee and Thomson.

‘It was no use thinking of taking a single off Thomson to get to the other end,’ said Denness. ‘You then had Lillee thundering in at you.’

The West Indies were similarly intimidated the following summer, with only a young Viv Richards, on his first tour, enhancing his reputation, though fellow rookie Michael Holding showed great promise.

Only two batsmen, Keith Boyce and captain Clive Lloyd, averaged in excess of 40. The worldbeating Lawrence Rowe averaged just 24 and champion-in-the-making Gordon Greenidge, 2.

The Windies won only three of their 13 first-class matches, their solitary Test win coming in Perth when Roy Fredericks teed off and Andy Roberts bowled seriously fast, taking nine wickets for the match including seven for 54 as the Australians were beaten by an innings. Lillee went for six an over, Thomson, seven, left-armer Gary Gilmour almost eight, and Walker, five.

It was an aberration in a series otherwise dominated again by the Aussie speedsters. In Melbourne, Lillee and Thomson took 13 wickets between them to restore the balance. Almost 86,000 attended the opening day, Thomson taking the first five wickets and Lillee four of the last five. Only the in-form Fredericks made 50, though Lloyd’s 102 in the second innings was a brave effort against the odds.

Along with Brisbane, 1974, it was the pair’s most successful Test match together.

‘In Thomson and Lillee they possessed the best combination of fast bowlers any captain could wish for,’ Lloyd said, ‘and our batsmen, especially early in an innings, were constantly under pressure. None of them had ever encountered bowling of such speed before.’

In Perth, Lloyd was struck in the jaw and Alvin Kallicharran’s nose was cracked by Lillee. In Sydney, stand-in opener Bernard Julien had his thumb broken by Thomson.

‘If no-one else received any actual broken bones, everyone at some stage did feel the pain of a cricket ball thudding into their bodies at 90 miles an hour,’ said Lloyd.

Injuries and Kerry Packer’s rebel World Series Cricket movement were to restrict their future influence as a pair. Lillee was one of the headline early WSC signings, but Thomson remained in traditional ranks, being rewarded with his country’s vice-captaincy for the 1978 tour of the West Indies under Bobby Simpson. He even led in an island game and ambled out with 11 others and calmly said, ‘I’m bowlin’. The rest of yez spread out.’ On being told that Australia had 12 players on the field, he said, ‘One of youse nick off.’

It wasn’t until Mr Packer funded a WSC tour of the Caribbean in 1979 that the Lillee-Thomson partnership resumed. In five Supertests they amassed 39 wickets between them, Lillee 23 and Thomson 16, including 11 in the first Supertest at Sabina Park, Jamaica. They were still fast and threatening, but by then Thomson had had his shoulder reconstructed after a collision with teammate Alan Turner and had lost just a little of his zip.

The following ‘compromise’ summer, they played the first two of the summer’s six Tests together, without sharing the new ball. Their last appearance side-by-side was against the West Indies in Adelaide in 1981–82, Lillee breaking down with a groin injury in his fifth over. In the second innings, acting captain Marsh opened with Thomson and Len Pascoe. Even off-spinner Bruce Yardley was preferred to Lillee. A pulsating, ever-so-pacy era was over.

|

DENNIS LILLEE’S TEST OPENING PARTNERS |

|

|

Matches |

|

|

17 |

Jeff Thomson |

|

13 |

Terry Alderman |

|

11 |

Max Walker |

|

9 |

Rodney Hogg |

|

8 |

Geoff Dymock |

|

6 |

Gary Gilmour, Bob Massie, Len Pascoe |

|

3 |

Geoff Lawson |

|

1 |

David Colley, Tony Dell, Ashley Mallett, Carl Rackemann, Alan Thomson |