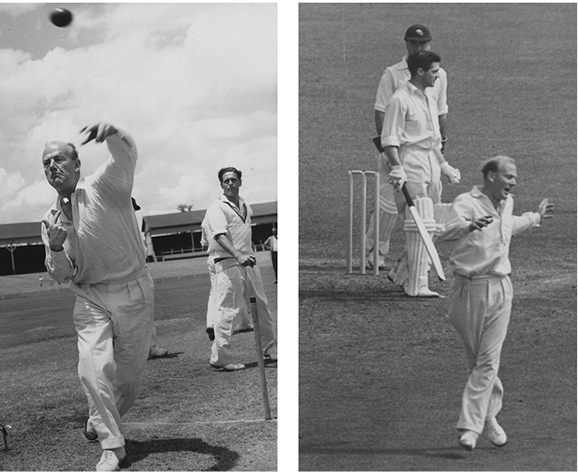

Surrey Kings: Jim Laker (left) and Tony Lock (far right) with another strike bowler, noted fast-medium Peter Loader. They were among those most responsible for lifting Surrey to unprecedented success at English county championship level in the 1950s.

N

‘They were sitting ducks for Laker, who drifted and spun his off-breaks so wickedly across the batsmen that his leg trap arsenal, including the eagle-eyed Lock, thought Christmas had come early…’

A NEAR MIRACLE

Putting aside, for now, the Edgbaston epic of 2005, it was as gripping a finish to a cricket match as any I have witnessed in 50 years. To be one of the 18,000 filing into the Melbourne Cricket Ground on the fifth day of the heart-stopping 1982 Christmas Test was a privilege and a pleasure.

Set 292 runs to win and reclaim the Ashes, Australia was cruising at 3–171 before England’s Jamaican-born speedster Norman Cowans engineered a middle-order collapse. The Australians lost six wickets for 47, including top-scorer David Hookes for 68, as England revived. Only one wicket separated England from a convincing win and a 2–1 mid-series scoreline with the deciding Test to come in Sydney.

Enter Australia’s No. 11, Jeff Thomson, an express bowler of still intimidating pace, but without the accompanying batting credentials.

Meeting him in centre wicket was 27-year-old Allan Border, highest score 32 all summer, fighting for the right to remain in Australia’s top six. Having been out for 2 in the first innings in Melbourne, Border knew he was on the brink. He either had to make runs in the second innings or be replaced for the final Test in his home town of Sydney the following week.

‘I hadn’t been playing particularly well and my position in the side was in question,’ he said. ‘I started that [second] innings under a lot of pressure. There was a two-fold situation at the beginning of the innings. One was to get Australia over the line and [two to] make sure I scored enough runs to keep my Test career going. It was touch and go for a while. I had nothing much to lose. I went out there and played my own game.’

Demoted one slot to No. 6, he was in at 4–171 and watched on as Cowans tore through the middle and late order on a relaid wicket starting to keep menacingly low. Rod Marsh and Rodney Hogg were lbw and Bruce Yardley bowled, giving Cowans three more wickets for just five runs from 20 balls. It had been a sensational return given that he’d failed to take a wicket in the first two Tests and been dropped from the third. At 9–218, Australia still needed an additional 74.

‘Given Jeff’s previous batting history, it was unlikely we were going to win the game,’ said Border. ‘As we lost wickets it became more important for me to hang in there and dig a little bit deeper.’

The umpires Tony Crafter and Rex Whitehead extended play by half an hour, thinking the game would finish in four days. But rather than capitulate meekly, Thomson played some solid defensive shots, backing his partner, who began to play with his old authority, using a bat, minus its stickers, borrowed from Ian Botham.

Border expertly manipulated as much of the strike as possible, Thomson having to face only one or two deliveries most overs. Slowly but surely, the Australians whittled down the required runs to 60, 50 and then 40.

The crowd willed the Australians on. By stumps, the scoreline had improved to 9–255. Just 37 more were needed. It shaped to be a magnificent finish… or so the public thought.

Walking down from the Hilton Hotel the next morning, the Australians were amazed to see Yarra Park alive with so many streaming in. Greg Chappell thought they were all mad. He’d written the game off.

The gates had been thrown open on the fifth morning, the Australians dispensing with their normal team warm-up, only Border and Thomson having a brief hit-up.

They couldn’t help but sense the expectation. Even before 11 am, the crowd had swelled to almost 10,000 and was to double during one of the best-remembered hours at cricket’s colosseum.

As they walked out to roars of approval, Thomson said if it was good enough for all the fans to come, they should give it their absolute best. In the dressing rooms the Australians resumed the exact seats they’d been in the night before. Those like Geoff Lawson, who’d been downstairs, remained in the dungeon, relying on updates from the room attendant.

‘We were something like 200/1 to win,’ said Border. ‘Eighteen thousand people get lost a little at the MCG but they were making enough noise for 40,000 or 50,000. Their support made us all the more determined to win or, at worst, lose gloriously.’

Tracking a seven-for, Cowans bowled the first over from the members’ end and Thomson either let the ball go or defended like he was an accomplished top-order player. There was widespread cheering and applause as each ball was successfully negotiated. Cowans’ second over, too, was a maiden, Thomson in little discomfort against the old ball.

Border, meantime, was scoring ones and twos. England captain Bob Willis had spread the field wide, allowing Border easy runs to help get Thomson back on strike.

Play had re-commenced at a somewhat leisurely pace, but as the partnership grew so did the noise in the crowd, the confidence of the two batsmen and the anxiety of the Englishmen.

When Cowans took the second new ball at 11.29 am, there were cheers as, after a prolonged delay with the field being re-set, Thomson confidently square-cut his first delivery to third man for a single.

Only five runs came in the first half an hour – a hush proceeding every delivery before excited chatter and applause as deliveries were either defended or allowed to fly harmlessly through to wicketkeeper Bob Taylor.

The 50 stand came in 92 minutes, when Thomson played another cut shot, this time squarer through point, and the batsmen scampered three.

There was a further roar when Allan Lamb and substitute fieldsman Ian Gould collided as Border stole a daredevil single to again keep the strike. When the replay of the collision was shown on the big board – in use for the first time – the crowd erupted again. The Englishmen were now the hunted. Willis was fast running out of options. By not pressuring the Aussies early, he’d allowed both to settle and they were playing beautifully, the crowd an increasing factor.

‘Every time a single was scored or Jeff played out an over, the crowd went berserk,’ said Border. ‘The pressure built up. You could see the Englishmen succumbing. It was a couple of great hours of Test cricket. Extraordinarily 18,000 people turned up to see what possibly could have been one ball. They were the smart people that morning.’

Less than 20 were needed for a famous win and there were gasps when Border nicked Bob Willis through where second slip would have been, only for Willis’ insistence at spreading the field. He was playing Border back into form.

Minutes before, Thomson had played an ungainly cut shot which ballooned towards point and landed safely. It could so easily have been caught, only for him to take a single and escape to the safety at the non-striker’s end. Looking up at the replay screen he quipped to umpire Crafter: ‘Arrrr, that didn’t look too good, did it!’

Crafter said the tension was almost unbearable. Having given Thomson not out to an ever-so-close run-out call the night before – and seen a replay vindicating his decision later that night – Crafter prayed that no-one would be hit on the pads.

Having bowled five overs for eight runs, Willis introduced Ian Botham, but even the champion all-rounder couldn’t induce a false stroke and, to screams of delight, Border and Thomson further reduced the target. Less than a dozen were needed and there were often two and three minute delays between overs for consultations between a clearly worried Willis and his deputies.

‘It was an incredible situation,’ said Border. ‘Here was the No. 11 bloke trying very hard and [together] we were pulling something special out.’

Thomson was on strike and just four were needed as Botham was again entrusted with the ball. In between overs there had been screams of support. Many stood as Botham ran in to deliver the first ball of his twenty-sixth over. It was a little wide and Thomson fanned at it only to get a big edge. At the non-striker’s end Border initially thought it was sailing over the slips to the boundary, only to see it loop virtually straight into the hands of second slipsman Chris Tavare. He grabbed at it, the ball ballooning over his shoulder, only for some quick-thinking by Geoff Miller at first slip to turn and take the ball on the rebound.

England had won by three runs in the closest Ashes Test since 1902. Miller and Botham embraced and sprinted for the pavilion and an afternoon of celebration.

Thomson was close to tears as he entered the Australian rooms.

‘He took the defeat badly, having fought so hard for so long, only to be pipped by three lousy runs,’ said Hookes. ‘The atmosphere in our room was suitably sombre. Then Marshy sang out: “Don’t worry, we’ll get ’em in Sydney.” For once [captain] Greg Chappell was not impressed with Marsh’s timing and snapped: “Rodney, just shut up and let the batsmen sit down and console themselves.”’

With 68 not out, Border had been incredibly stoic. Never again was his place to be in jeopardy.

‘We’d gone within a whisker of pinching it,’ he said. ‘It was another defeat, unfortunately. But it captured people’s imagination and brought that Test series to life. We had been 2–0 up coming to Melbourne. Now the Poms were back in the series.’

The fifth and deciding Test in Sydney was to be drawn, the revitalised Border scoring 89 and 83. Promoted to No. 10, in his final Test on Australian soil Thomson made 0 and 12.

For all of his sheer pace, frightening spells and 200 Test wickets, the big Queenslander is remembered just as much for that one last famous stand with Border. It had been a near miracle.

SCORES: England 284 and 294 defeated Australia 287 and 288.

NEW ZEALAND’S FINEST

Ian Smith can still remember the battering his hands took standing back to master paceman Richard Hadlee on the 1984 tour of Sri Lanka. New Zealand’s long-time stumper says he nursed ice-packs courtesy of Hadlee every night and sometimes during the day as well.

Despite all the bruises, they had a great relationship, and at Lancaster Park in 1988, on the morning that Hadlee was due to become Test cricket’s new wickets record-holder, Smith approached and wished him good fortune.

‘Get it quickly so we can all relax a bit.’

‘If it wasn’t for you, pal, I would already have the record by now!’

‘Caught Smith, bowled Hadlee’ appeared in New Zealand Test scorebooks on 43 occasions. There were another 19 catches in one-dayers. They were a great combo, New Zealand’s finest of all.

NINE DEFINING DAYS

For all of their hundreds of wickets together, and their pivotal roles in Surrey’s remarkable run of championships in the 1950s, the careers of spin-twins Jim Laker and Tony Lock were defined in nine early summer days when England stormed from one Test down to retain the Ashes in the final riveting fortnight of July 1956.

In taking 18 Australian wickets at Leeds and all 20 at Manchester, the pair bowled Australia out four times in nine days, England winning back-to-back Tests by an innings.

‘Laker was an ogre,’ said Australia’s captain Ian Johnson. ‘That we succumbed so repeatedly to him is a credit to his bowling rather than an indictment of our batting.’

At Headingley, the Australians were bowled out for 143 and 140, and at Old Trafford for 84 and 205, Laker taking 11 wickets and Lock seven at Leeds, and Laker an incredible 19 and Lock one at Old Trafford.

Having won the second Test on a grassy green wicket at Lord’s, the Australians were told by opposing captain Peter May, ‘That’s the last one of those you’ll see.’

Leeds was a dustbowl and Manchester even worse. Old Trafford’s curator Bert Flack had been ordered on the eve of the match to cut and re-cut the remaining grass by England’s selection chairman GOB ‘Gubby’ Allen. Initially he’d complained, saying the pitch couldn’t possibly hold together. When rain came in mid-match, it made the wicket as treacherous as any Melbourne sticky-dog. Laker launched through the star-studded Australian batting line-up from the Stretford end, taking nine for 37 in the first innings – including a run of seven for 8 in 22 balls – and all ten for 53 in the second.

Lethal: At his very best, Tony Lock was almost as destructive as Jim Laker. Neil Harvey fell to him in both innings at Trent Bridge in the opening Test of the 1956 Ashes tour.

In wreaking unparalleled havoc on the Australians, who boasted first-class centurions in every position from No. 1 to No. 11, Laker became an instant celebrity and the bowler who beat the might of Australia with just one hand. It had been 51 years since England had twice defeated Australia in a home series. Without the combative Lock building pressure like few left-arm spinners before or since, Laker admitted his fairytale figures wouldn’t have been achievable.

So often did the Australians play and miss at the vicious turn of Lock, that he became totally exasperated. Often he would pitch outside leg and it would still miss off. Several deviated almost at right-angles to slip and were simply too good for the batsmen. There were only two left-handers in Australia’s side, Neil Harvey and Ken Mackay. The rest were right-handers and they were sitting ducks for Laker, who drifted and spun his off-breaks so wickedly across the batsmen that his leg trap arsenal, including the eagle-eyed Lock, thought Christmas had come early. In his only two Ashes Tests, Alan Oakman took two catches at Headingley and five at Old Trafford.

Ex-England wicketkeeper Les Ames said: ‘The Australians were not good players of off-spin. They gave up the ghost. Jim, with his marvellous control, turned the ball at right-angles.’

As the players were walking off, Laker in front having taken his nineteenth and final wicket, England captain May approached Lock and said: ‘Well bowled, Tony. Forget the scorebook. You played your part too.’

Writing a generation later, English cricketer and cricket journalist Robin Marlar said it still amazed his contemporaries that Laker had so dominated the match, given the quality within the Australian team and the presence not only of Lock, ‘the most avaricious of bowlers’, but of Brian Statham and Trevor Bailey, ‘who bowled 46 overs without even one strike’.

‘Even if you accept that the 1956 Australians were not one of the best teams from that country, there were still great cricketers in the team: Harvey, Miller, Lindwall and Benaud,’ he wrote. ‘In truth, even though it happened, we can describe Laker’s feat only as incredible.’

Oakman had stood so close at leg slip that Miller came in and said: ‘That’s a dangerous position, Oakie. If I middle one, they’ll have to carry you off.’ Three balls later he was out: c Oakman, b Laker!

Despite bowling as well as he had at any time in his career, especially early in the match, Lock’s ‘share’ in 69 overs was just one wicket: opener Jim Burke, who was the third to fall in Australia’s first innings.

‘If my performance was unbelievable, then so was his,’ Laker was to say later. ‘If the game had been replayed a million times it surely would not have happened again. Early on he bowled quite beautifully without any luck at all and beat the bat and stumps time after time.’

Richie Benaud, who was out for 0 and 18, said the Australian right-handers ‘couldn’t lay a bat on Lock’, so far was he spinning the ball.

As Laker added scalp after scalp, Lock became increasingly frustrated at his failure to gain his share of the spoils. According to teammate Peter Richardson, also part of the leg trap, Lock began to bowl faster and faster and the right-handers were able to let many of his deliveries pass, whereas with Laker they were forced to defend, not being able to distinguish his top-spinner, which hurried straight on, from his signature off-break.

‘If Lockie had pitched the ball up more,’ said Richardson, ‘and bowled at a sensible pace, he must have got 10 out of 20.’

Lock left Old Trafford ‘in high dudgeon’, according to biographer Alan Hill. ‘The rift between them simmered for years,’ he said.

Laker may have been his bowling buddy but he was also his arch rival. Lock treated every innings of every game as a personal competition.

Laker was everything Lock wasn’t: right-arm, rhythmic, pure of action, more stable and gifted. Lock was left-arm, crustier, colourful, aggressive and very mercurial. He was also more controversial, being ‘called’ six times for throwing, including in a Test at Sabina Park.

‘Lockie was the greatest competitor I ever saw,’ said Laker, who years before had helped a teenage Lock with his grip and talked of the need to have a change-up ball, all the time learning to land it on a sixpence. The nets at the local Indoor School were low and Lock changed from having a high, pure action to a more jerky, flatter delivery which enabled him to bowl without hitting the top of the net. His faster ball was a good 25 per cent quicker than his orthodox finger spinner and his immediate returns for Surrey were astonishing.

Looking back on Old Trafford, 1956, Laker years later admitted that he should have shown more empathy with his long-time Surrey teammate.

‘On reflection over many years – and remembering that Tony has had to live with his “1–106” – I think I should probably have shown a bit more sympathy towards him than I did at the time,’ Laker said. ‘I have often tried to imagine how I would have felt if the boot had been on the other foot – as it could so easily have been.’

Australia was bowled out in 40.4 overs in its first innings and 150.2 in its second.

Coming into his game of games, Laker, then 34 and seven and a half years Lock’s senior, had taken just eight wickets in six Tests at Old Trafford, but from the first delivery of the game from Ray Lindwall, which barely bounced stump high, the Australians knew that it was an uneven playing field and that the grassless crew-cut wicket had been deliberately ‘doctored’ to suit the two Surrey champions.

Laker had taken 10 wickets in an innings against the tourists earlier in the summer when Surrey became the first county in 44 years to defeat an Australian touring team.

In the first Test he’d taken six wickets and in the second, three, before launching into the fortnight of his life. Umpire Frank Lee had the best seat in the house at Old Trafford and said many of the Australians pre-empted their shots, either going forward or back as Laker bowled, ‘without treating every delivery on its merits’.

|

JIM LAKER AND TONY LOCK FOR SURREY, 1949–59 |

||||

|

Season |

Laker wickets |

5wI |

Lock wickets |

5wI |

|

1949 |

97 |

7 |

37 |

– |

|

1950 |

111 |

9 |

53 |

1 |

|

1951 |

101 |

9 |

65 |

3 |

|

1952 |

86 |

7 |

85 |

3 |

|

1953 |

43 |

2 |

62 |

6 |

|

1954 |

96 |

10 |

94 |

6 |

|

1955 |

82 |

2 |

130 |

13 |

|

1956 |

45 |

2 |

57 |

5 |

|

1957 |

80 |

4 |

113 |

11 |

|

1958 |

83 |

6 |

95 |

6 |

|

1959 |

46 |

4 |

65 |

6 |

|

Total |

870 |

62 |

856 |

60 |

‘Apart from Richie Benaud,’ he said, ‘no-one really tried to attack the bowling of Laker, which was very strange when one recalls how harshly he was treated by the Australian batsmen of 1948 at Lord’s, in numbering nine 6s hit during one morning session.’

The Laker-Lock mastery that memorable summer was to continue into the fifth Test at their home ground The Oval, where the pair took 10 wickets, Laker seven and Lock three, increasing their summer aggregate to 61 (Laker a record 46 and Lock 15).

In 10 more Tests together, they collected 14 or more wickets in a game three times:

• 19 v New Zealand, Leeds, 1958

• 16 v West Indies, The Oval, 1957

• 14 v New Zealand, Lord’s, 1958

Their performances with Surrey were remarkable, the club winning eight championships in their time, including an unprecedented seven in a row from 1952 to 1958. Not once were they placed outside the top six counties during their incomparable golden era.

Laker was to achieve an ambition and finally tour Australia in 1958–59 – alongside Lock. In a strange twist, despite his pre-eminence as England’s finest post-war spin bowler, between his first and last Test matches he played just 46 of England’s 99 Tests and was not selected for back-to-back Ashes tours in 1950–51 and 1954–55.

Stunned to have missed the Ashes tour down under in 1962–63, Lock became one of the people most responsible in the rise of Western Australia as a Sheffield Shield power.