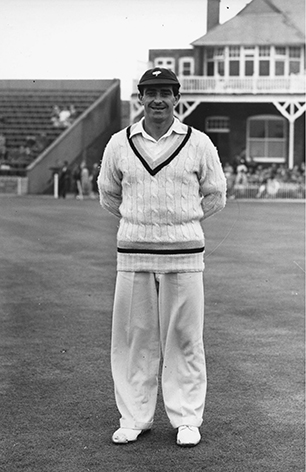

Charismatic: Yorkshireman ‘Fiery Fred’ Trueman (pictured), the senior partner in England’s most prolific new ball combine with the great Lancastrian Brian Statham.

O

‘Gees I am tired,’ said Ollie, ‘I can’t lift my friggin bag…’

‘OHHH, THAT NO-BALL!’

Kumar Sangakkara was walking off the Sinhalese Sports Club’s ground, having been bowled by emerging South African paceman Dale Steyn, when he was stopped by the umpires. It had been a no-ball. At the time, Sangakkara was 7. Two days later he and his captain, Mahela Jayawardene, were still batting, having broken every Test and first-class record in establishing a 624-run stand for the third wicket.

‘It was surreal to still be batting late on the third day,’ said Sangakkara. ‘Instead of being three for not many, we were two for 600 and plenty! Dale and I linked up later at Warwickshire and every time we ran into each other he’d say: “Ohhh, that no-ball!” It meant three days out in the field for South Africa, and in Sri Lanka that’s tough.’

Both amassed personal bests, Sangakkara 287 and Jayawardene 374, their partnership extending to 624, the grand-daddy stand of them all.

‘We thought one of them might get a bit bored once they’d gone past 150,’ said South Africa’s wicketkeeper, Mark Boucher. ‘That’s what normally happens in a big stand – someone will try and hit the ball out of the park. But they were phenomenal.’

Having offered some initial life, the wide, white wicket at the Sinhalese Sports Club flattened out to its most benign and batting-friendly and the two Sri Lankans prospered like no pair before or since.

‘We never planned it,’ said Jayawardene. ‘You can’t plan a partnership like that. It was a wonderful moment for us but it was also very nerve-wracking. Come tea on the third day we were told that we were just 16 behind the all-time record by Sanath [Jayasuriya] and Roshan [Mahanama at the Premadasa Stadium almost a decade earlier]. Never have I been more nervous over the scoring of 16 runs. We crawled our way there. I didn’t want to let my partner down. In the end we got there with four byes. It was a wonderful moment for us. Very enjoyable. We had so wanted to get over that hurdle. All these fire crackers went off as part of the celebrations. It was really something to be out there. Hopefully there’ll be another two Sri Lankans who will break our record.’

On both nights they were not out, the pair went out to dinner together with their families.

‘We certainly saw a lot of each other that week,’ said Sangakkara. ‘Mahela and I have always been close. I love batting with him. It’s so insightful to the way you should be batting. He sets a magnificent example.’

Six of the pair’s 14 century stands at Test level have come at the SSC. In 2004 against the South Africans they’d added 192.

The Proteas’ attack was world-rated. Ntini was ranked the No. 2 bowler in the world at the time. Steyn, then 23, was averaging almost four wickets a Test at home, while Andre Nel and finger spinner Nicky Boje were consistent.

Chancy early, Sangakkara had been dropped in the gully as well as being castled by an over-stepping Steyn before settling down and playing gloriously, the pair going virtually run for run, hardly offering even another half-chance.

At stumps on Day 1, Sangakkara was 59 and Jayawardene 55. On the second day they added 357, Sangakkara’s share 170 and Jayawardene 169, Sangakkara’s footwork sparkling as he took on Boje, often meeting him on the full toss and half volley and caressing the ball delicately through the offside. Jayawardene was just as technically correct and at 340 passed Jayasuriya’s Sri Lankan national record. He was zeroing in on Brian Lara’a Test high of 400 before missing a low one from Nel which cut back wickedly and scuttled his middle and off stumps. He’d batted for 14 hours and 32 minutes. Sangakkarra had earlier succumbed, flashing at a wide one. He’d batted for 11 hours and 15 minutes.

|

THE SCOREBOARD: SRI LANKA v SOUTH AFRICA |

||

|

First Test |

||

|

Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 27–31 July, 2006 |

||

|

Toss: South Africa |

||

|

South Africa 169 (de Villiers 65, Fernando 4–41, Muralidaran 4–41) and 434 (Rudolph 90, Hall 64, Prince 61, Boucher 85, Muralidaran 6–131) |

||

|

SOUTH AFRICA |

||

|

HH Gibbs, AJ Hall, JA Rudolph, HM Amla, AG Prince (c), AB De Villiers, MV Boucher+, M Boje, A Nel, DW Steyn, M Ntini |

||

|

SRI LANKA |

||

|

WU Tharanga |

c Boucher, b Steyn |

7 |

|

ST Jayasuriya |

lbw Steyn |

4 |

|

KC Sangakkara |

c Boucher, b Hall |

287 |

|

DPMD Jayawardene (c) |

b Nel |

374 |

|

TM Dilshan |

lbw Steyn |

45 |

|

CK Kapugedera |

not out |

1 |

|

Extras |

|

38 |

|

Total |

5–756 declared |

|

|

Fall: 6, 14, 638, 751, 756 |

||

|

Did not bat: HAPW Jayawardene+, MF Maharoof, SL Malinga, CRD Fernando, M Muralidaran |

||

|

Bowling: Ntini 31–3–97–0, Steyn 26–1–129–3, Nel 25.1–2–114–1, Hall 25–2–99–1, Boje 65–5–221–0, Rudolph 7–0–45–0, Prince 2–0–7–0, de Villiers 4–0–22–0 |

||

|

Umpires: MR Benson and BF Bowden |

||

|

Third umpire: EAT de Silva |

||

|

Referee: J Srinath |

||

|

Close of play scores: |

||

|

First day: Sri Lanka 2–128 (Sangakkara 59, Jayawardene 55) |

||

|

Second day: Sri Lanka 2–485 (Sangakkara 229, Jayawardene 224) |

||

|

Third day: South Africa 0–43 (Rudolph 24, Hall 13) |

||

|

Fourth day: South Africa 4–311 (Prince 60, Boucher 38) |

||

|

Man of the match: Mahela Jayawardene |

||

|

Sri Lanka won by an innings and 153 runs |

||

|

Second Test (P. Saravanamuttu Stadium): Sri Lanka won by 1 wicket |

||

|

Sri Lanka won series 2–0 |

||

|

+ denotes wicketkeeper |

||

|

CENTURY PARTNERSHIPS IN INTERNATIONAL CRICKET BETWEEN KUMAR SANGAKKARA AND MAHELA JAYAWARDENE |

|

|

Test Cricket (14)* |

|

|

624 |

v South Africa, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2006 |

|

311 |

v Bangladesh, Asgiriya Stadium, Kandy, 2007 |

|

193 |

v India, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2010 |

|

192 |

v South Africa, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2004 |

|

173 |

v Pakistan, Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore, 2001–02 |

|

173 |

v New Zealand, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2009 |

|

168 |

v South Africa, Durban, Kingsmead, 2000–01 |

|

162 |

v West Indies, Galle, 2001 |

|

158 |

v Pakistan, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2005–06 |

|

135 |

v Bangladesh, Shere Bangla National Stadium, Mirpur, 2008–09 |

|

122 |

v England, Kandy, 2007–08 |

|

119 |

v South Africa, Pretoria, 2002–03 |

|

101 |

v Australia, Pallekelle, 2011 |

|

101 |

v Australia, Sinhalese Sports Club, Colombo, 2011 |

|

One-Day Internationals (13) |

|

|

200 |

v India, Bellerive Oval, Hobart, 2011–12 |

|

179 |

v Canada, Hambantota Cricket Stadium, 2010–11 |

|

159 |

v England, Headingley, Leeds, 2011 |

|

153 |

v India, Adelaide, 2007–08 |

|

151 |

v India, Jaipur, 2005–06 |

|

150 |

v Bermuda, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, 2006–07 |

|

145 |

v New Zealand, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai, 2010–11 |

|

140* |

v England, Chester-le-Street, 2006 |

|

121 |

v Australia, Dambulla, 2003–04 |

|

116 |

v India, Dambulla, 2004 |

|

104 |

v India, Dambulla, 2010 |

|

102 |

v Pakistan, Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, 2011–12 |

|

100 |

v Australia, Brisbane, 2005–06 |

|

Twenty20 Internationals (1) |

|

|

166 |

v West Indies, Bridgetown, Barbados, 2010 |

|

* all third-wicket stands |

|

|

TEST CRICKET’S TOP FIVE BATTING PARNERSHIPS |

||

|

Runs |

Wicket |

Batsmen |

|

624 |

Third |

Kumar Sangakkara (287) and Mahela Jayawardene (374)Sri Lanka v South Africa, Colombo (SSC), 2006–07 |

|

576 |

Second |

Sanath Jayasuriya (340) and Roshan Mahanama (225)Sri Lanka v India, Colombo (RPS), 1997–98 |

|

467 |

Third |

Andrew Jones (186) and Martin Crowe (299)New Zealand v Sri Lanka, Wellington, 1990–91 |

|

451 |

Second |

Bill Ponsford (266) and Don Bradman (244)Australia v England, The Oval, 1934 |

|

451 |

Third |

Mudassar Nazar (231) and Javed Miandad (280*)Pakistan v India, Hyderabad, 1982–83 |

|

And also: |

||

|

446 |

Second |

Conrad Hunte (260) and Garry Sobers (365*)West Indies v Pakistan, Kingston, 1957–58 |

|

438 |

Second |

Marvan Atapattu (249) and Kumar Sangakkara (270)Sri Lanka v Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, 2003–04 |

|

437 |

Fourth |

Mahela Jayawardene (240) and Thilan Samaraweera (231)Sri Lanka v Pakistan, Karachi, 2008–09 |

|

*denotes not out |

||

Not only did the pair break the all-time Test partnership record of 576, they went past the previous highest first-class partnership record of 577 held by Vijay Hazare and Gul Mohamed in India’s Ranji Trophy in 1947.

Along with the World Cup triumph in 1996 and Muthiah Muralidaran’s 800 wickets, it remains the proudest moment of all in the annals of Sri Lankan cricket.

THE OLD FIRM

There has been no more celebrated English new-ball pairing than Brian Statham and Freddie Trueman. While not as physically threatening as Bodyliners Harold Larwood and Bill Voce, or as enduring as Yorkshire’s Golden Age combo George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes, they were mighty warriors: the larger-than-life Trueman downwind, froth, bubble and swing; Statham into it, patient, probing and pacy, the true master of economy.

As new-ball partners, they would occasionally gift singles to turn around batsmen, allowing Trueman open season on the right-handers with his natural, often-late outswing, and Statham, the lefties with his signature nip-backers.

Side-by-side they took 284 wickets in 35 Tests together at eight a match: Trueman 143 at 25.76 and Statham 141 at 25.71. It’s one of cricket’s quirks that only once did they each take four or more wickets in the same innings, against the star-studded West Indies on the final day of the Trent Bridge Test in 1957.

The Statham-Trueman pairing was responsible for 52 of the 79 South African wickets taken by English bowlers in their golden summer of 1960. England dominated from the opening Test at Edgbaston, winning 3–0.

Possessing the purest of side-on actions with the shoulder strength of a prize fighter, the ego-driven, limelight-seeking Trueman was essentially all attack. He’d bowl his bouncer often and at the throat, even if only to wake up the crowd. Occasionally he overstepped the mark, but a smile and an appeasing one-liner would invariably follow, like in the opening over of the Melbourne Test of 1962–63 when he struck local hero Bill Lawry clearly outside the line of the leg stump, yet appealed vociferously for leg before. Walking back past first-time umpire Bill Smyth, he joked in that broad Yorkshire accent of his: ‘Just wanting to see if thee were awake!’ Later that tour, a young Greg Chappell was among the crowd in Adelaide when there was a 21-gun salute to mark Australia Day. On hearing the first shots, Trueman, at the head of his run-up, immediately tumbled over as if he’d been shot.

‘It was great theatre,’ said Chappell. ‘That was Fred for you. He always liked the limelight.’

Trueman’s smile and earthy manner opened doors wherever he went. In 1956 when the Australians were Lakered on a monstrous wicket, they initially baulked at signing a bat for the curator Bert Flack, who they felt had bowed to pressure from the top and provided unfair conditions. Trueman, who was twelfth man, marched into the visitors’ rooms with the bat and obtained the signatures himself, one-by-one.

As a bowler, Trueman offered more width and scope for batsmen than Statham, but his best balls could be unplayable, as he regularly reminded tailenders: ‘Wasted on thee,’ was a favourite one-liner.

He’d cornered the headlines from the time he smashed and grabbed 29 wickets in four maiden Tests against a terrified India in 1952, and survived just as many downs as ups, becoming the first, in 1964, to 300 Test wickets. Along the way, in 1963, he passed Statham as the world’s new No. 1 wickets record holder, a milestone Statham enjoyed for just six weeks.

The sheer quality of his bowling enabled him to survive and keep his many detractors at bay. On the 1958–59 trip, Marylebone manager and ex-captain Freddie Brown twice threatened to send Trueman home, once when they were boarding the SS Iberia when Trueman spoke sharply to him in front of the squad, and again after the first Test, which Trueman missed with lumbago. Only the timely intervention by captain Peter May, who told Brown to give Trueman space, stopped what was building towards a career-ending Full Monty of altercations.

The ever-smiling, highly durable Statham was England’s premier bowler in the 1950s, despite Frank Tyson’s speed blitzes of 1954–55 and Jim Laker’s heroics of 1956. Had he not made himself unavailable, ‘George’, as he was affectionately known, could easily have found himself on a fifth Ashes tour in 1965–66. A captain’s dream, he could bowl a maiden over with his eyes closed. And they were eight-ball overs on tour back then. No international-class bowler could build pressure as effectively. So rarely did the double-jointed Lancastrian ever bowl a bad one that master cricket writer Neville Cardus once asked, semi-seriously, whether Statham had ever bowled a wide! Consistently faster than Trueman, his off-cutter could be lethal, and in 1958–59 in Adelaide, he almost bent Australia’s opening batsman Colin McDonald in two with the opening delivery of the match.

‘I still don’t know how it missed the off bail,’ said McDonald, who went on to make 170. ‘It was just about as good a delivery as I ever received… certainly the best not to get me out.’

Statham’s motto was, ‘If they miss, I hit.’ He loved bowling extended spells à la Alec Bedser, and at breaks would often talk to his feet: ‘Come on lads,’ he’d say. ‘Just another two hours and I can put you up for the night.’ Tyson said he never saw Statham have breakfast. Instead, he’d content himself with a cigarette, a cough and a cup of coffee.

On four tours to Australia, the first as a reinforcement, Statham took more than 100 wickets, including 43 in the Tests. In 1954–55, when Trueman controversially missed selection for reasons other than cricket, Statham shared the new ball with the cyclonic Tyson, and was integral to England’s remarkable revival.

While Tyson built ferocious, near-100-mph pace from a shorter run-up he’d first trialled at Alf Gover’s cricket school, the almost-as-quick Statham maintained high pressure, shutting down the Australian players and taking 18 wickets himself. On the New Zealand leg of the tour, without even a warm-up, Tyson was timed at 99 mph and Statham at 97 mph.

In England’s famous 38-run win in Sydney, Tyson said his fast bowling mate ‘burst his lungs bowling into the breeze for 85 minutes, while I surfed downwind to take 10 wickets. It was the same in Melbourne where he breasted the breeze for 90 minutes to take two for 19 as the Aussies collapsed. [Tyson taking seven for 27 as Australia was bowled out for 111, the two walking off with their arms around each other’s shoulders.] My 28-wicket series contribution was in no small part due to Australian batsmen’s eagerness to escape from Brian.’

The MCC team’s manager, Geoffrey Howard, said Statham’s relentless accuracy was the perfect foil for Tyson’s thunderbolts.

‘Brian always got a lot of wickets for the bowler at the other end,’ he said. ‘He gave nothing away and the Australians like to get on with it. They don’t like maiden overs.’

With his fluid approach and rhythmic, front-on action, Statham could bowl at high speed, not as rapid as Tyson at his top, but still consistently around 90 mph. Old foe McDonald felt him consistently quicker than Trueman, and second only to Tyson, as the best English fast bowlers he faced in the 1950s.

For a fast bowler, Statham was the gentlest of souls. So much effort did he put into his delivery action that the knuckles of his bowling hand all but kissed the pitch. At just 12 st 4 lb he was pencil-thin, and the rigors of bowling long spells most days would see him lose 8 or 9 lb most tours. The shock of having to bowl in 100-degree heat on his first tour in Australia taught him to conserve his energy. He streamlined his action and bowled even faster with the minimum of effort. In 1953, on his Ashes debut at Lord’s, he thumped a lifter flush into the chest of Australia’s centurion Keith Miller, who was visibly discomforted. Rather than intimidate opponents with bouncers, he’d much rather hit their stumps. In the 1953–54 Test at Port-of-Spain, West Indian Frank King felled England tailender Jim Laker with a bouncer, breaking the code that tailend batsmen should not be subjected to bouncers. Come the next match in Jamaica, Trueman was all about retribution and readily involved himself in ‘chin music’ to the retreating King. Urging Statham to do the same, he was told, ‘Nay Fred, I think I’ll just bowl him out.’

Trueman and Statham were paired in one Ashes Test in 1956, two in 1958–59, three in 1961 and in all five in 1962–63, when Trueman took 20 wickets and Statham 13.

Neil Harvey, Australia’s finest batsman of the 1950s, considered Trueman the finer all-round bowler, yet he fell more often to Statham (10 dismissals to nine). The only other international to be dismissed more times by Statham was also left-handed: South Africa’s Trevor Goddard. In 1958–59 in Melbourne, the Test in which Ian Meckiff torpedoed England, Statham’s Ashes-best seven for 57 kept England in the game early. Four of his wickets were bowled or lbw and two more caught by wicketkeeper Godfrey Evans. His line was immaculate.

|

FREDDIE TRUEMAN’S FAST BOWLING PARTNERS |

|

|

Number of Tests |

|

|

35 |

Brian Statham |

|

5 |

Alec Bedser, Peter Loader |

|

3 |

Len Coldwell, Alan Moss, Derek Shackleton, Frank Tyson |

|

2 |

Trevor Bailey, David Larter, Fred Rumsey |

|

1 |

Jack Flavell, Les Jackson, John Price, Harold Rhodes |

Trueman’s mega Ashes moment came at Leeds in 1961 before his adoring home crowd, when he took 11 wickets for the match to beat Australia almost single-handedly. Having lost at Lord’s, England revived emphatically with an eight-wicket win, Trueman following his five for 58 with six for 30. In the second innings, he slowed his pace and at one stage had five for 0 in 27 balls, his lethal off-cutter triggering Australia’s remarkable slump from 2–99 to 120 all out.

The legendary commentator John Arlott was an unabashed fan, writing: ‘Statham was accurate, Tyson was fast; Fred was everything.’

THE OLD GREY MARE

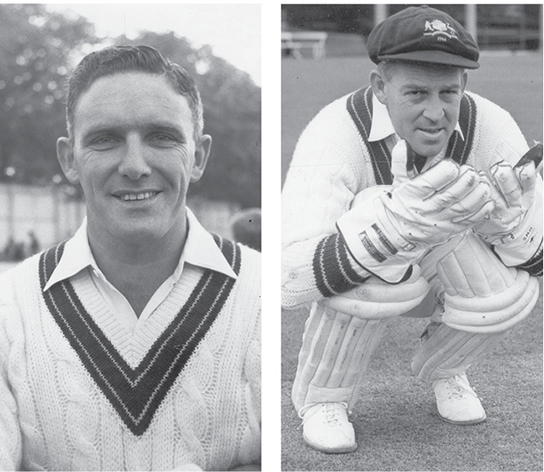

When Alan Davidson asked bosom buddy Wally Grout for a complimentary copy of his autobiography, My Country’s Keeper, in 1965, he was immediately told that he could afford to buy his own! Within days, however, one duly arrived, signed and inscribed: ‘To the man I made!’

‘Davo’ always reminded his long-time mate that for Grout to get his name into the scorebook, he had to hit the edge first! The pair shared a wonderful rapport and friendship and remain among the greatest of all Australian bowler-wicketkeeper combinations.

Grout, cricket’s ultimate team-man, was a talented extrovert who had the eye of an eagle and rare anticipation. He provided another set of ever-so-expert eyes for his captains, urging, encouraging and plotting, and along the way taking some of the great catches as Australia prospered again after the dim, dark days of the Ashes-forfeiting tour of England in 1956.

Davo was integral in Australia’s rejuvenation. Thrust key responsibility with the retirements of champion new-ball duo Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall, he was a master of his craft, becoming the best performing left-arm paceman in the world with the rare ability to swing the ball around corners, from right to left and left to right. He could bend it even on the sunniest days when everyone else was bowling gun-barrel straight. His party trick was to duck one or two back into the right-handers before, with no discernible change of action, running one across them, often inducing an edge through to the willing mitts of Grout.

In 28 Tests together, ‘c Grout, b Davidson’ was responsible for 44 catches at a rate of 1.6 wickets per Test, a superior ratio than even the record-breaking combo of ‘c Marsh, b Lillee’. Most notably there was a forty-fifth wicket for the pair, a Grout-inspired stumping in Madras, 1959–60, that was one of the great post-war dismissals.

Old mates: Alan Davidson (left) with his long-time wicketkeeping buddy Wally Grout.

During Australia’s extended tour of the sub-continent, Grout noticed an increasing number of grey hairs around the Davidson temples, ensuring lively banter between the two. Madras was the seventh of eight Tests in 10 weeks and Davidson’s workload had finally caught up with him. The heat and humidity this mid-January day was stifling, and so exhausted was Davidson that he’d slowed from his normal briskish medium to slow medium. Had the speed gun been in vogue back then, he would have been lucky to have clocked a Mike Hussey-ish 115 km/h. On the first two deliveries of this particular over, Grout shuffled closer and closer to the stumps, and as Davidson wearily trudged back to the top of his mark for his third delivery, Grout cheekily took up occupation right next to the stumps, as if Davidson was bowling slow spinners like Benaud or Lindsay Kline.

Grout knew what was coming next. Davidson stopped at the top of his run and angrily eyeballed the Queenslander, and told him to resume his normal position – otherwise he’d land one straight between his eyes!

Instead of retreating, Grout stayed where he was and began singing a few bars of ‘The old grey mare she ain’t what she used to be…’ followed by another most-audible aside to slipsman Neil Harvey: ‘Has anyone ever stood in front of the stumps?’

Satisfied he’d sufficiently upset his mate, he went into his normal crouch, grinning like a Cheshire cat.

Davidson’s initial reaction was to bowl as fast a bouncer as he could and make Grout’s hands tingle. If he happened to get his head in the way, so much the better. It would teach the so-and-so a lesson. Just as he was running in, he changed his mind, opting to sling one wide, which Grout wouldn’t be able to stop. The resultant four byes would be a bigger blow to the Grout ego than any hit to the head. Down it went, way wide of off-stump with all of Davidson’s remaining energy, and the Indian batsman MM Sood did his best to connect, only to over-reach and lose his balance. Just as Grout was taking the ball ever-so-nonchalantly in his outstretched right hand, he saw Sood spreadeagled in front of him, with not even a shoelace behind the crease. Cartwheeling his arm at the stumps, he broke the wicket in an instant. Sood was out – the only stumping of Davidson’s illustrious career! It was an inspired take. Glancing sideways at the square leg umpire for confirmation, Grout calmly walked up the wicket and handed the ball back to Davo with a deadpan: ‘And it didn’t even spin, Al!’

STATS FACT: Grout also had a telling combination with Richie Benaud with 15 catches and 11 stumpings in 32 matches.

OLD PALS

They opened together for just one riotous season but the fun, frivolity and happy memories remain.

Colin ‘Ollie’ Milburn, Western Australia’s roly-poly English import, captivated crowds throughout the 1968–69 Sheffield Shield season with his daredevil strokeplay. Built like a tank, 17-stone Ollie would whack cuts, pulls and drives all off the front foot. Teammates would try to retreat to other nets for fear of being hit by one of his explosive straight hits.

His opening partner, Derek Chadwick, was a Perth sporting star good enough to represent his state at both football and cricket and also make an Australian B team to New Zealand.

On practice nights, Ollie and ‘Chaddie’ loved to have their net and, still with their pads on, wander back into the rooms early and devour the king’s share of the large plate of quarter-cut sandwiches faithfully laid out by the West Australian roomie, Alfie Morgan. No-one could eat like Ollie. He’d grab a handful and without even bothering to see what was in them, down them in a single gulp. Then he’d go off for ‘a feed’. By the time the rest of the team came in, invariably only a few offcuts would remain.

‘We decided enough was enough,’ said Western Australia’s long-time vice-captain Ian Brayshaw, ‘so we had the girls in the kitchen prepare some “special” sandwiches for Ollie and Chaddie, and Alfie duly brought them out. We sneaked in early to have a look and both boys were looking decidedly green, especially when we brought out the just-opened half-empty can of Pal dog food!’

The pair were great mates, Chadwick happy to have the best seat in the house as Ollie whacked them. The only time the rotund one would take a single was from the last ball of an over so he could stay on strike.

In that 1968–69 season they made century starts three times, including an extraordinary 328 in four explosive hours against Queensland at the Gabba. One hundred and forty-seven runs came in the first session and 181 in the second. The temperature hovered at around 100 degrees and Milburn was absolutely spent by tea. Within a minute or two afterwards he was out.

Chadwick had a wicked sense of humour and one day borrowed a hammer and some extra long nails from the curator’s shed and hammered Ollie’s kitbag to the floor.

‘Gees I am tired,’ said Ollie, ‘I can’t lift my friggin bag!’

The payback came within days. Chadwick arrived in the rooms to find his brand new Slazenger hanging from the rafters with a dozen holes power-driven from back to front. Advantage Milburn.

Chadwick never did admit to a follow-up episode when a live cat was found in Ollie’s locker, but it made one ungodly mess!

They averaged 100 runs per partnership throughout 1968–69. The only other pair to surpass their average were Golden Age heroes Victor Trumper and Reggie Duff, who averaged 102 for New South Wales at the turn of the century.

|

TOP AVERAGES OF OPENING PAIRS IN SHEFFIELD SHIELD CRICKET |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Team |

Span |

Innings together |

Best |

Total |

Average |

|

Victor Trumper and Reggie Duff |

New South Wales |

1902–08 |

14 |

298 |

1332 |

102 |

|

Colin Milburn and Derek Chadwick |

Western Australia |

1968–69 |

11 |

328 |

1007 |

100 |

|

Jack Fingleton and Bill Brown |

New South Wales |

1932–35 |

24 |

249 |

1719 |

78 |

|

Kepler Wessels and Martin Kent |

Queensland |

1980–82 |

18 |

246 |

1063 |

66 |

|

Bob Simpson and Grahame Thomas |

New South Wales |

1962–66 |

22 |

308 |

1244 |

62 |

|

Sam Trimble and Ray Reynolds |

Queensland |

1959–64 |

35 |

256 |

1928 |

56 |

|

Ken Meuleman and Colin McDonald |

Victoria |

1947–50 |

11 |

337 |

621 |

56 |

|

Bill Lawry and Ian Redpath |

Victoria |

1962–69 |

51 |

204 |

2857 |

56 |

|

Bob Simpson and Ian Craig |

New South Wales |

1961–62 |

15 |

161 |

772 |

55 |

|

And the most prolific: |

|

|

|

|||

|

Matthew Elliott and Jason Arnberger |

Victoria |

1996–05 |

98 |

353 |

5084 |

53 |

|

Matthew Hayden and Trevor Barsby |

Queensland |

1991–97 |

87 |

243 |

4423 |

52 |

Left: Test Cricket Resumes: Bill Brown and Ken Meuleman open for Australia in the first post-war Test match in Wellington in 1946. While Brown topscored with 67, Meuleman was dismissed without scoring in his one and only innings for Australia.

Right: Interstate Champions: Jason Arnberger (left) and Matthew Elliott built a remarkable combination at Sheffield Shield level for Victoria. Together they made more than 5000 runs with 16 century starts. Getty Images/Cricket Victoria

OUTSTAYING THEIR WELCOME

Bill Brown and Jack Fingleton were among the most successful of all between-the-wars Sheffield Shield openers, but they could outstay their welcome.

‘On good days we’d bat until lunchtime,’ Brown said. ‘But if we happened to go along too much afterwards, the crowd would start to get restless. You see, you were batting in Bradman’s time! If you happened to get hit on the pads, not only would the bowler and the field go up, but so would everyone else in at the ground. When you got out you got the most tremendous ovation, not because you’d played well, but because you were getting out of the way for Don! It was nothing for the crowd to double and even treble over lunch with the prospect of Bradman batting. If he happened to get out, there’d be this mass exodus for the turnstiles.’

Brown loved batting with the Don. He had the best seat in the house as the master went about his business.

‘One day we [New South Wales] played Victoria at the [Sydney] Cricket Ground. I got going early and needed about 30 for my 100 and the second new ball was just about due. Don was batting with me and he said: “Bill, we must get your 100 before the next new ball” and proceeded to just take singles, feeding me the strike at every opportunity. I duly got my 100 and he was about 16 or 17. By the time I was into my 120s, he’d passed me! And all in about an hour’s cricket.’

In addition to averaging 78 opening up for New South Wales, Brown and Fingleton averaged 103 together during their golden tour of South Africa in 1935–36. Included were three century stands and a 99 in four Tests.

OVER TO YOU, ARTHUR

Vic Richardson and Arthur Gilligan would chat away like two old married magpies during their Ashes cricket broadcasts on the ABC. So popular were the two old Ashes captains that the Sydney Bulletin even devoted a page of cartoons to the pair’s one-liners: ‘What do you think, Vic?’ and ‘What do you think, Arthur?’

From 1936 to 1937 and again after the War, the Richardson-Gilligan combine was synonymous with cricket on the airwaves.

Their friendship stood the test of time, Gilligan even sending a special cheerio to Vic from 13,000 miles away during the fifth Test in one of his last broadcasts at The Oval in 1964.