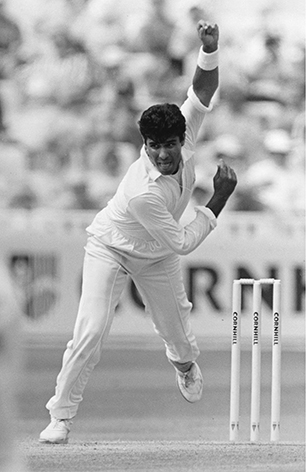

Tearaway: Even Wasim Akram conceded the wind to his formidable pace partner Waqar Younis (pictured), one of the masters of high speed reverse swing. Patrick Eagar

S

‘When JB Hobbs is out in the centre, he calls the tune and we dance to it…’

SERVICE ABOVE AND BEYOND

Influential St Kilda Cricket Club president RL ‘Doc’ Morton and his right-hand man, the club’s long-time secretary Bert Inskip, formed a wonderful off-field partnership, ushering in a halcyon period for the famous seaside club that resulted in six between-the-wars premierships, including an unprecedented four in a row from 1923–24 to 1926–27. Few matched Inskip’s passion for the game. He attended every club committee and sub-committee meeting for 38 years – in one season there were 34 meetings – and during the war years worked for nothing. He was also a club delegate at Victorian Cricket Association level and served on the St Kilda Football Club committee, lifting his meetings aggregate to 1000-plus!

SIMPLY PEERLESS

As soloists they were sublime; as a pair, scintillating. For a decade Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe formed England’s mightiest and most revered partnership of all. Even 80 years after their last appearance, their average of 87 runs per innings is unsurpassed.

Their epic liaison hastened an English cricket renaissance. In England’s first 15 Tests after World War I, 10 other openers apart from Hobbs had been tried, several never to be picked again. In the very first over of their first innings together against the 1924 South Africans at Edgbaston, Sutcliffe was all but run out without having even faced a ball after Hobbs called him through for a sharpish single, only to suddenly send him back. Sutcliffe was still yards short when the throw from close range at mid-on missed the stumps. The throw wasn’t backed up by the bowler and the opportunity was lost. The pair added 136, the first of 15 century stands in Tests.

As they’d walked to the wicket for the first time, Hobbs, then 41, said nothing more than, ‘Play your own game, Herbert.’ Sutcliffe, 12 years his junior and appearing in his first Test, took one look at Hobbs with his confident, assured stance and immediately felt at ease.

‘There I felt was a man in complete control of himself as well as the situation we were facing… he was… a rare source of inspiration and strength to the youngster at the other end.’

Sutcliffe, a Yorkshireman with a cool temperament and a thumping hook shot, was to amass in excess of 50,000 first-class runs. His Test average of 60 eclipsed even Hobbs, scorer of a record 197 first-class centuries. Hobbs was more stylish and adaptable on all wickets, but Sutcliffe had a ‘an unruffled calm’ and tenaciousness which distinguished him from every other champion of the generation. He had no problems with Hobbs cornering the strike and said he never stopped learning from ‘The Master’. Once when Hobbs played and missed several times in one over – a most unusual occurrence – Sutcliffe walked down the wicket at the end of the over and said: ‘Stick it, Jack. He [the bowler] can’t keep that up.’

The pair would toy with opposing fielders, luring them closer as they stole short singles, to help open the boundaries for their attacking shots.

Australia’s captain Herbie Collins dubbed Hobbs ‘The Ringmaster’. When asked to explain, he said: ‘When JB Hobbs is out in the centre, he calls the tune and we dance to it.’

HSTL ‘Stork’ Hendry said no pair could judge a run like Hobbs and Sutcliffe. ‘You knew they were going to steal singles. It didn’t matter a damn how you placed the field, they still got the singles.’

The great alliance was never more effective than on back-to-back Australian tours from the mid-1920s, where they amassed six of their 11 century stands, four in 1924–25 and two in 1928–29.

The wickets down under were like billiard tables, wide, white and flat. Games often spilt into a second week. Only the run-ups were covered, however, and if there was any rain, combined with fierce sun, as often occurred down south in Melbourne, batting conditions could be hazardous. But wet, dry, sunny or overcast, the Hobbs-Sutcliffe union prospered.

Their stands were worth 97 runs per innings in 1924–25 and 54 in 1928–29, when Hobbs turned 46. Series by series they made:

• 1924–25: 157, 110, 283, 36, 63, 126, 0 and 3

• 1928–29: 85, 25, 37, 28, 105, 143, 1, 64 and 1

From their appearance in the opening Test in Sydney in 1924–25, when the pair survived the menacing bounce of expressman Jack Gregory and the testing outswing of Charlie Kelleway, they played confident, dominating cricket. Sutcliffe felt Hobbs was initially a little unbalanced by Kelleway’s away swing and, after the first over, met him in mid-pitch advising him to leave anything angling towards the slips alone, especially while the ball was new. Hobbs was the game’s most celebrated player and Sutcliffe’s advice could have been deemed impertinent, but Hobbs welcomed it. Later he wrote: ‘I knew we’d found the right opener for England.’

Having added 157 in the first innings, they started with 110 in the second, only for the Englishmen to be easily beaten.

Coming to Melbourne for the New Year, where the Test was to last seven days, they shared their most famous stand, 283, and became the first to bat through an entire day’s play, a monumental achievement given Australia had amassed an Ashes-best 600 over the first two days.

Neither gave a chance, Hobbs going to stumps on 154 and Sutcliffe 123. It was riveting, near-perfect cricket, one of the finest achievements in Ashes annals. Remarkably, Sutcliffe was also to bat through the sixth day on his way to twin hundreds.

‘It was English cricket at its best,’ wrote former Australian Test captain MA ‘Monty’ Noble. ‘You only had to remember the total that glared in the face of these men as they went out to open the innings to realise the mental as well as the physical effort that was necessary to overcome the feeling of hopelessness, which certainly dominated the minds of every well-wisher in the crowd. Six hundred was the greatest total ever made in a Test! It could not be beaten! But that is not England’s way; and if cricket teaches anything at all, it is that you are never beaten while a wicket remains intact.

‘For a whole day they defied every change of bowling that could be brought against them. They simply played on and on, now in admirable defence, now in vigorous aggression, but always cautious, always confident… they seemed unconquerable.’

The heat was ferocious and the Australian attack well balanced with the speed of Gregory, Kelleway’s testing mediums, and the wafty leg-breaks of Arthur Mailey, who on the previous MCC visit to Melbourne had become the first to take nine wickets in an innings.

Hobbs’ plan was to ‘tame Jack’ and ‘if we can we could be here for a considerable time’. Gregory had captured seven wickets in Sydney and like the greatest fast bowlers had a habit of taking wickets in a hurry. Yet even he could not elicit even a half-chance from either Hobbs or Sutcliffe as they scored 70 in the first session, 117 in the second and 94 in the third.

‘No brilliant century or two could save her [England], nothing but dogged perseverance, chanceless play, hour after hour,’ said PR Le Couteur, writing in the English Cricketer. ‘Such play these two gave us. They were content with ones and twos, stealing with complete safety scores of runs by perfect judgment in running. They scored a four only when it was utterly safe. At one period, when Sutcliffe was about 40, he brightened, hit one or two balls with full vigour, but wisely took himself to task and returned to the routine of the job. The great crowd was quite satisfied and relished the grim fight. The cheers which greeted the two weary batsmen [at the end of the day] could not have rung louder at Lord’s or The Oval.’

Hobbs’ own MCG first wicket record of 323 with Wilfred Rhodes seemed likely to be surpassed, but he missed a flighted full toss in Mailey’s first over on the Monday and was bowled. Sutcliffe later blamed Hobbs’ refusal to have even a short hit-up that morning for missing the ball, which landed on the popping crease. Teammates blamed the harsh Australian sun, saying Hobbs hadn’t been sufficiently acclimatised to play the ball correctly.

Among the MCG crowd of almost 50,000 on the Saturday had been the wife of Australia’s cricket-loving Prime-Minister-to-be Robert Menzies. Unlike her husband, Pattie Menzies had little interest in cricket and she went home early as Hobbs and Sutcliffe batted on and on.

‘We were in England in 1926 and Bob suggested we should go to at least one game in England,’ she said, ‘so down to The Oval I went, Australia playing England, and there they were again, Hobbs and Sutcliffe. They were still batting!’

The 283-run partnership was the closest the pair were to get to the triple-century milestone in Australia, but there were some stellar moments ahead, especially in 1928–29 when Percy Chapman’s team successfully defended the Ashes, winning the first three Tests in a row in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. The MCG win was a particularly momentous one, as England successfully chased 332 on a ‘sticky dog’ of a wicket on which Hobbs and Sutcliffe miraculously started with 105, after Hobbs had been missed at 3, a relatively easy chance to Stork Hendry resting at slip. He’d been struck a tremendous blow in the chest earlier in the game by Harold Larwood and wore a six-stitcher bruise for a fortnight afterwards.

The game again went seven days and it seemed the Australians must win after heavy overnight rain which softened the unprotected wicket. (By law, only the run-ups were covered.) Play was delayed until almost 1.30 pm and the wicket was like putty when play resumed under increasingly sunny skies. The ball left divots and pock marks on the drying pitch, encouraging extraordinary, steepling bounce and danger to the batsmen. Test veteran Hugh Trumble, the secretary of the Melbourne Cricket Club, felt an all-out score of 100 would be a good effort on ‘such an unplayable wicket’. Even Hobbs conceded that the Englishmen were ‘up against it’.

Watching on from the old open-air press box adjacent to the MCC committee room, Englishman Percy Fender felt the wicket had ‘behaved as badly as it could’.

‘About three balls in five hopped head- or shoulder-high, some turning as well and some stopping almost visibly as they hit the ground. The batsmen were hit all over the body from the pads to the shoulders and in two or three cases, even on the neck and head – all from good or nearly good length balls.’

Behind the stumps, Bert Oldfield was having a nightmarish time, conceding more than a dozen byes.

Sutcliffe preferred to be hit rather than offer a catch to any of the close-in fieldsmen clustered around the bat. One spitting delivery to Hobbs knocked his cap off and the cap flew just wide of the wicket. Among the few aggressive shots either allowed themselves was the cross-batted pull. They played back at every opportunity, dropping their hands expertly to allow rising balls to harmlessly pass. It was as fine a defensive display as any seen at the cricketing colosseum.

|

TEST CRICKET’S ELITE OPENING PAIRS, ON AVERAGE |

||||||

|

|

Innings |

Not Out |

Runs |

Best |

Average |

100s |

|

Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe (England) |

38 |

1 |

3249 |

283 |

87 |

15 |

|

Allan Rae and Jeff Stollmeyer (West Indies) |

21 |

2 |

1349 |

239 |

71 |

5 |

|

Jack Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes (England) |

36 |

1 |

2156 |

323 |

61 |

8 |

|

Len Hutton and Cyril Washbrook (England) |

51 |

3 |

2880 |

359 |

60 |

8 |

|

Bill Lawry and Bobby Simpson (Australia) |

62 |

3 |

3596 |

382 |

60 |

9 |

|

Sadiq Mohammad and Majid Khan (Pakistan) |

26 |

3 |

1391 |

164 |

60 |

4 |

|

Trevor Goddard and Eddie Barlow (South Africa) |

34 |

2 |

1806 |

134 |

56 |

6 |

|

Roy Fredericks and Gordon Greenidge (West Indies) |

31 |

2 |

1593 |

192 |

54 |

5 |

|

Sunil Gavaskar and Chetan Chauhan (India) |

59 |

3 |

3010 |

213 |

53 |

10 |

|

Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer (Australia) |

113 |

4 |

5655 |

255 |

51 |

14 |

|

Geoff Boycott and John Edrich (England) |

35 |

2 |

1709 |

172 |

51 |

6 |

|

And the most prolific: |

||||||

|

Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes (West Indies) |

148 |

11 |

6483 |

298 |

47 |

16 |

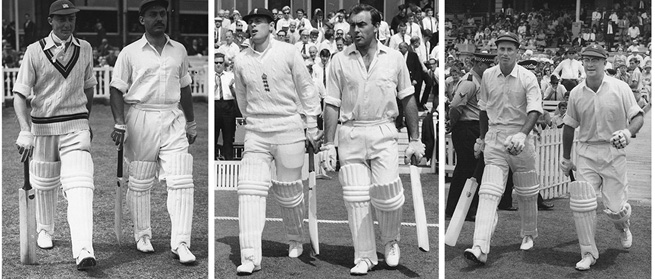

Left: Windies greats: Jeff Stollmeyer (left) with Allan Rae.

Centre: English Icons: Geoff Boycott (left) with John Edrich.

Right: Springboks: Trevor Goddard (left) with Eddie ‘Bunter’ Barlow.

Australia’s captain Jack Ryder changed his bowlers frequently, realising that the wicket must improve and that unless the Australians made more inroads into the top-order, the extra rolling of the wicket on the following morning would all but cancel any wet weather advantage the Australians had enjoyed. While Hobbs finally succumbed in the final session, Sutcliffe and Douglas Jardine carried England through to 1–171 at stumps and within sight of a famous victory. Sutcliffe registered his fourth century in five innings on the final day, England securing victory with seven wickets down. It had been one of the great fourth-innings chases, Hobbs and Sutcliffe again playing pivotal roles on a wicket on which others would almost certainly have succumbed.

On the penultimate night, Hobbs had called for a new bat and Jardine, due to bat at No. 6, took it out ahead of the twelfth man Maurice Leyland. According to Hobbs’ biographer Leo McKinstry, Jardine was whispering some congratulations about Hobbs’ brave stand with Sutcliffe when Hobbs cut him off in mid-sentence and said: ‘I want you to come in next.’

|

JACK HOBBS’S MOST FAMOUS PARTNERS IN FIRST-CLASS CRICKET |

|

|

|

100 stands |

|

Andy Sandham |

67 |

|

Tom Hayward |

40 |

|

Andy Ducat |

29 |

|

Herbert Sutcliffe (15 in Tests) |

26 |

|

Ernie Hayes |

15 |

|

Wilfred Rhodes (eight in Tests) |

14 |

|

Tom Shepherd |

12 |

|

100-RUN OPENING STANDS IN TESTS BETWEEN HOBBS AND SUTCLIFFE |

|

|

283 |

v Australia, Melbourne, 1924–25 |

|

268 |

v South Africa, Lord’s 1924 |

|

182 |

v Australia, Lord’s 1926 |

|

172 |

v Australia, The Oval, 1926 |

|

157 |

v Australia, Sydney, 1924–25 |

|

156 |

v Australia, Headingley, 1926 |

|

155 |

v West Indies, The Oval, 1928 |

|

143 |

v Australia, Adelaide, 1928–29 |

|

136 |

v South Africa, Edgbaston, 1924 |

|

126 |

v Australia, Melbourne, 1924–25 |

|

125 |

v Australia, Trent Bridge, 1930 |

|

119 |

v West Indies, Old Trafford, 1928 |

|

110 |

v Australia, Sydney, 1924–25 |

|

108 |

v Australia, Old Trafford, 1930 |

|

105 |

v Australia, Melbourne, 1928–29 |

Jardine had a rock-solid defensive game and was more suited to the situation than England’s champion No. 3 Walter Hammond. While Jardine made only 33, he lasted until stumps and on the following day, on an improved wicket, England made the Ashes-securing runs despite a flurry of late wickets by the Australians, which saw four wickets go down for just 10 runs when the tourists were within 15 runs of victory.

Hobbs had been long talking of Test retirement but was so pivotal to the fortunes of English cricket that he continued to be picked, including for all five 1930 Tests against the Australians, when he and Sutcliffe averaged almost 65 with century stands at Old Trafford and Trent Bridge.

Hobbs, 47, retired with a record 3636 Ashes runs at an average of 54. Sutcliffe continued in Tests until 1935, when he was 40. His Ashes average was 66. They were remarkable players and, as a pair, cricket’s incomparable supremos.

SRI LANKA’S FINEST

No Test team has had a greater reliance on two frontline bowlers than Sri Lanka with its two ‘go-to’ men, Muthiah Muralidaran and Warnakulasuriya Patabendige Ushantha Joseph Chaminda Vaas – the fast bowler with the longest name in cricket.

Paired together in 95 Tests, Murali, from Kandy and Chaminda Vaas, from tiny Wattala, a fishing town just north of Colombo, captured 62.2 per cent of Sri Lanka’s wickets at almost 10 wickets a Test. Even their high-profile contemporaries Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath collectively averaged just 50 per cent of Australia’s wickets.

Seventy-two of their 95 Tests were on the sub-continent or in Zimbabwe, where they are particularly famed. They played together just three times in Australia and five times in England.

Their ability to bowl long spells and build pressure from each end was pivotal, both at Test and One Day International level, where they were similarly successful.

Murali, the Wisden Bowler of the Century and the first to 800 Test wickets, was incredibly successful, his extraordinary flexibility of shoulder and wrist allowing him to turn the ball both ways. His detractors reckoned he simply threw the ball, but from birth both he and his brother Sasi Daran had both been unable to fully straighten their arms. Murali may have bowled with a bent arm, but he also finished with a bent arm.

He polarised opinions from the time he opposed Allan Border’s Australians in 1992–93.What was never questioned was his extraordinary ability to spin the ball à la Shane Warne on even the flattest, most batting-friendly wickets. His perfecting of an off-spinner’s flipper to go with his ripping off-break and doosra ushered in a halcyon period of personal and team success for the Test cricketing minnow. Warne’s action may have been purer, but Murali struck more often. And, as his team’s only Tamil, he helped unite a nation torn for years by civil war.

In a 20-year period, Sri Lanka won only six of 39 Tests when Murali was absent.

Vaas was also a wonderful ambassador, mentor and hero for hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankans. His rare ability to curl his left-arm swingers at medium pace, no matter the state of the ball, saw him become the youngest Sri Lankan, at 21, to take 10 wickets in a Test against the 1994–95 New Zealanders in Napier, when Sri Lanka won its first-ever overseas Test.

When both Murali and Vaas played, the Sri Lankans won 43 per cent of their matches. That percentage plunged to just 23 per cent if one, or both, were absent.

With Vaas in the same team, Murali averaged 6.17 wickets per Test and 5.63 when he wasn’t. Vaas averaged 3.25 wickets per Test when Murali played and 2.88 when he didn’t.

‘It was always reassuring to see Chaminda at the other end,’ said Murali. ‘He is a very proud Sri Lankan and it showed every time he went out. It didn’t matter the ground, the conditions or who we were playing, he always had a wide smile and he wanted the ball in his hand. If you have that sort of attitude, appetite and passion for the game, you’re a long way down the road to success.’

Murali was Sri Lanka’s player of the series 11 times and man of the match 19 times, his best match analysis a staggering 16 for 220 against England at The Oval in 1998. He took 10 wickets in a match in four consecutive Tests in 2001 and repeated the feat in 2006 as part of an amazing calendar year which saw him collect a near-record 90 wickets.

Vaas was to amass more than 350 Test wickets and remained competitive even when his pace had slowed. Due to play his one hundredth Test against the Australians in Hobart in 2007, he was dismayed to be dropped and told a friend who had arranged a commemorative trophy in his honour to throw it in the bin.

STOUSHING AT KENSINGTON OVAL

It was a stand which all but caused an almighty stoush – between Australia’s captain and vice-captain!

Tempers rose at cricket-crazy Kensington Oval, Bridgetown, as the West Indians clawed their way back into the fourth Test of the 1955 series courtesy of a mammoth 348-run partnership between local heroes Denis Atkinson and Clairmonte Depeiza.

Australia had started with 668 and seemed assured of another huge win when, in reply, the Windies slumped to 6–147 late on the third day. There was just half an hour to play when wicketkeeper Depeiza joined his Barbados teammate Atkinson. Rather than defending, they played old-fashioned calypso cricket, adding 40 against the bowling of Ray Lindwall and Richie Benaud.

There was no hint of what was to come: they were about to bat through three epic sessions on the following day, mixing stern defence with some cavalier strokeplay which had the locals dancing in delight. In five hours, the pair remained unbeaten, taking the score to 6–494; Atkinson adding 196 and Depeiza, known as ‘The Leaning Tower’, exactly 100.

Australia’s vice-captain Keith Miller had been dealt some severe treatment by 18-year-old local phenomenon Garry Sobers, who struck seven 4s from his first three overs. Kensington locals pointed and whistled at Miller as he aimed some retaliatory bouncers at their rising young champion. In his second spell, bowling against a strong crosswind, Miller took two of the first six wickets to fall, Everton Weekes and Collie Smith in the same over, both caught at the wicket by Gil Langley from slower-than-normal curling deliveries which bent away to the slips.

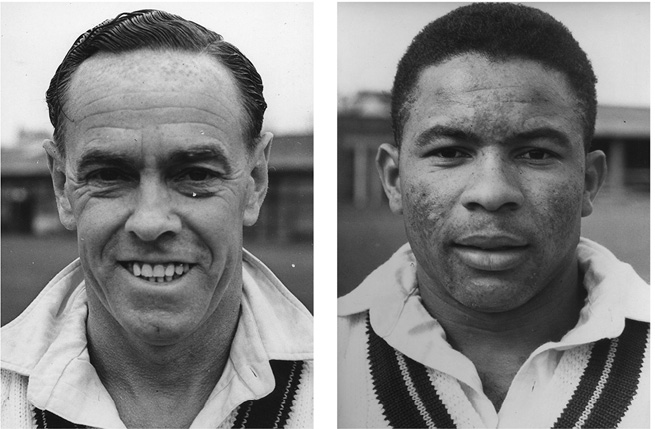

Left: Loggerheads: Australian captain Ian Johnson all but came to blows with his deputy captain Keith Miller at Kensington Oval, Bridgetown in 1954–55.

Right: Newboy: Collie Smith from Jamaica made a century on debut earlier in the series, but missed out at Kensington Oval.

Instead of allowing Miller an extended time at newcomer Depeiza, captain Ian Johnson immediately replaced him with Lindwall.

‘It was the one point on which the captaincy of Johnson could be criticised,’ said Percy Beames in the Melbourne Age. ‘Miller was openly displeased at being taken off. He was anxious to atone for the loss of face suffered at the hands of the young left-hand opener Sobers.’ His first seven overs had cost 43, but he had claimed two key wickets.

The Australians toiled throughout the fourth day without even one wicket. Colin McDonald at cover point grassed the only genuine chance late in the day, with Atkinson on 195, from the bowling of Lindwall.

‘It was a sitter, too,’ said McDonald. ‘Straight in and straight out again.’

The two West Indians scored 95 in the first 90-minute session, 135 in the second two-hour session, and 77 in the last 90-minute session, Miller being given just 15 overs all day, despite the taking of the third new ball at 427.

In the morning session Johnson had preferred to use Ron Archer with the second new ball alongside Lindwall, Miller not having his first bowl until immediately after lunch.

Atkinson and Depeiza raced to their first 100 in just 84 minutes before the introduction of spin saw the skiddy wrist spinner Jack Hill. Johnson so slowed the scoring rate that six maidens were bowled in a row, Depeiza defending his wicket as if it was the last match he’d ever play. Hill tried to force him back and set him up for his ‘lbw ball’, the quicker top-spinner, but Depeiza kept reaching forward, his concentration unerring. At one stage he’d advanced his score by just two while Atkinson made 50.

The scoring rate lifted again with Miller’s reintroduction. Atkinson greeted Miller with a four for his century immediately after lunch and Depeiza also started to play more freely. Unhappy at his team’s lack of success, Johnson recalled the spinners, but Atkinson was as severe on Benaud as Sobers had been on Miller the previous afternoon.

With the third new ball due, Johnson recalled Miller and he bowled a particularly furious spell, striking Depeiza several times on the chest and arms before he was replaced again. It had been an incredibly frustrating day for the Australians.

No Australian team in 30 years had ever fielded through a single day’s play without a wicket. Atkinson and Depeiza had batted 91 overs without being separated. The volatile Miller felt he’d been under-bowled and said so in the tiny visitors’ rooms, openly accusing Johnson of inept captaincy and how he couldn’t lead a bunch of schoolboys. Johnson bristled with rage and immediately invited Miller outside.

‘Things got nasty and blows were threatened,’ said McDonald. ‘The players had the highest possible regard for Miller, but in this case, we all knew he was in the wrong. We immediately put a stop to the silly nonsense and the journalists covering the tour missed a bonanza.’

|

MOST RUNS IN PARTNERSHIP (batting together twice) |

|||

|

Partnerships total |

|||

|

480 |

Don Bradman and Bill Ponsford (Australia) |

451 and 29 |

v England, The Oval, 1934 |

|

457 |

Ricky Ponting and Michael Clarke (Australia) |

386 and 71 |

v India, Adelaide, 2011–12 |

|

433 |

Dilip Vengsarkar and Sunil Gavaskar (India) |

89 and 344* |

v West Indies, Calcutta, 1978–79 |

|

422 |

Colin Cowdrey and Peter May (England) |

11 and 411 |

v West Indies, Edgbaston, 1957 |

|

402 |

Inzamam-ul-Haq and Younis Khan (Pakistan) |

324 and 78* |

v India, Bangalore, 2004–05 |

|

397 |

Justin Langer and Ricky Ponting (Australia) |

248 and 149* |

v West Indies, Georgetown, 2003 |

|

390 |

Javed Miandad and Mushtaq Mohammad (Pakistan) |

252 and 138 |

v New Zealand, Karachi, 1976–77 |

|

389 |

Bob Simpson and Bill Lawry (Australia) |

382 and 7 |

v West Indies, Bridgetown, 1965 |

|

384 |

Mohammad Yousuf and Younis Khan (Pakistan) |

142 and 242 |

v India, Faisalabad, 2005–06 |

|

379 |

Mohammad Yousuf and Younis Khan (Pakistan) |

363 and 16 |

v England, Headingley, 2006 |

|

374 |

Clairmonte Depeiza and Denis Atkinson (West Indies) |

347 and 27 |

v Australia, Bridgetown, Barbados 1955 |

|

372 |

Don Bradman and Jack Fingleton (Australia) |

26 and 346 |

v England, Melbourne, 1936–37 |

|

* denotes not out |

|||

Miller and Johnson may have hailed from the same club, South Melbourne, and been in the same Victorian and Australian teams, but they were never close, Miller knowing Johnson to be a ‘Bradman man’. Once the more conservative Johnson was preferred as Test captain, the rift widened even further.

‘I find there are times when I like Keith immensely,’ Johnson wrote soon after the tour, ‘and there are times when I dislike him intensely.’

Years later when Brian Hansen and I were launching Wild Men of Cricket, Miller was one of the past champions happy to attend.

‘You have names in the book [from Miller’s childhood] that I’d forgotten about,’ Miller said. Asking who else had been invited to the launch, he was told he could sit beside his old teammate Johnson.

‘Why invite him?’ he said. ‘You don’t want any wowsers there. Isn’t it all meant to be a bit of fun?’

Atkinson and Depeiza’s stand was to last into the fifth morning. Generations on, it remains the highest seventh-wicket stand in Test history. They paired up again late on the sixth and final day, adding 27 more without being separated as the West Indies clinched a most meritorious draw.

Their two Barbados partnerships totalled 374 runs, breaking the 20-year record held by Don Bradman and Jack Fingleton of 372 over two innings in the 1936–37 Melbourne Test.

More than 50 years and 1600 Tests later, their two innings’ aggregate still remains among the top 10 match partnerships of all time.

STRIKING EVERY 46 BALLS

‘If I was able to come back as a cricketer,’ Allan Border said once, ‘I’d come back as Wasim Akram.’ A Rolls-Royce among cricketers and, in Sir Donald Bradman’s view, the most menacing and successful left-arm fast bowler in history, Wasim mowed through even the most elite batting line-ups, his late each-way swing the envy of even the legends. Tall and whippy, Wasim captured more than 900 international wickets and was Pakistan’s pivotal player for almost two decades. Steve Waugh faced all the name fast bowlers from Malcolm Marshall and Curtly Ambrose to Michael Holding and Allan Donald, but one super-charged spell from Wasim at Rawalpindi in 1994 was ‘quicker and meaner’ than anything he’d faced before or since.

‘Either Wasim didn’t like me or I was in the wrong place at the wrong time,’ said Waugh. ‘Nothing was in my half of the wicket and it was all genuinely quick.’

When his explosive sidekick Waqar Younis arrived with his late-dipping, express yorkers, suddenly there was nowhere to run and nowhere to hide. Waqar welcomed Waugh this day with a searing, high-speed bouncer which all but cleaned him up, helmet and all. As he extended his follow-through he hissed at the Australian, ‘I’m gunna kill you today!’

‘Thought you were supposed to be quick,’ said Waugh, as usual revelling in the fight.

It remains one of his few regrets in cricket that a lifter from Waqar cracked his ribs, landed on his toe and spun back onto his wicket, dislodging the leg bail when he’d made 98.

Despite the Wasim-Waqar onslaught, Australia scored 500-plus, one of the few times the fury of the two champion Pakistanis went unrewarded.

Throughout their outstanding reign as cricket’s most successful new-ball pairing, Wasim and Waqar averaged five wickets an innings at an average of one strike every 46 balls. Even on flat wickets and in heat-wave conditions they were electric, Wasim with his reverse swing and steepling bounce from just short of a good length, and Waqar with his sheer pace and late swing. Had they had more back-up and had the Pakistanis assumed a more appealing profile as one of the game’s genuine powers and been granted full-length series, instead of just two and three Tests here and there, they could have added the world Test championship to their one-day silverware.

England’s Graham Gooch said batsmen never felt settled when opposed by Wasim.

His lethal second spell was pivotal in the Pakistanis winning the 1991–92 World Cup in Australasia, including the final against England at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in front of almost 88,000 fans. He was the outstanding player in the match, his withering efforts from around the wicket accounting for England’s last big hope, Allan Lamb, and the dangerous Chris Lewis, both bowled just when the Englishmen were threatening.

‘It was a do-or-die spell and Wasim dismissed Lamby and Chris Lewis in successive balls, each one almost unplayable,’ said Gooch. ‘He always had the ability to raise his game on the big occasion.’

Wasim was equally effective bowling over or around the wicket, when he could lope in behind the umpire and explode into his delivery stride at the very last moment. The Australians reckoned he was playing peekaboo, but no-one dared complain – not until he’d retired! On approach he’d cup the ball in both hands until the very last moment so the batsman on strike couldn’t see the shiny side of the ball and anticipate which way it was likely to swing.

Umpire Rudi Koertzen said Wasim’s momentum through the crease was ‘incredible’ and, with the clatter of his spikes on the wicket, he made so much noise it was sometimes impossible to hear the nicks. ‘He was just so hard to umpire,’ he said.

Even from his shorter than normal run-up, Wasim bowled a ‘heavy’ ball. Melburnians who witnessed Wasim taking his first five wickets for just 13 runs in a World Championship of Cricket match one Sunday in the mid-1980s knew that the teenager from Lahore had special talents. He beat Kepler Wessels and Kim Hughes for pace and Allan Border was so flustered by a short one that he hit his own wicket. Dean Jones was another in the Australian top-order to succumb. Teammate Javed Miandad said he’d simply ‘paralysed’ the Australians. It was an extraordinary burst.

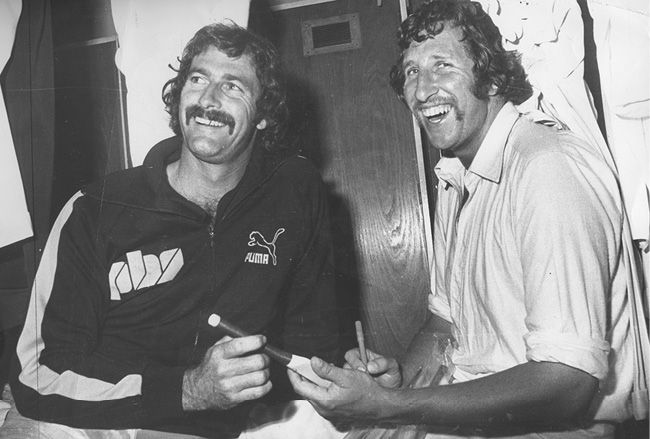

All Smiles: Another of Dennis Lillee’s famed new ball partners was the Tasmanian-born Max Walker. They took 16 wickets between them in the 1977 Centenary Test. Cricketer magazine

After his mentor Imran Khan was too old to bowl fast, Wasim carried Pakistan’s attack for years before the arrival of Waqar, ‘The Burewallah Express’, who surged to the wicket with increasing momentum before an explosive delivery leap and whippy, slingy action which saw him deliver the ball at speeds upwards of 90 mph.

So fast was the teenage speedster that Wasim soon relinquished the wind and found his unique late swing was even more pronounced.

‘I didn’t mind,’ said Wasim. ‘Waqar had the longer run-up and coming into it was good for reverse swing. He was an incredible bowler. He’d run in [with purpose] every ball. He had real attitude about him. He was good on every sort of wicket and that’s what a young bowler needs to aspire to.’

|

PARTNERS IN PACE |

||

|

Innings opened |

|

Last Test together |

|

89 |

Waqar Younis and Wasim Akram (Pakistan) |

2001–02 |

|

86 |

Courtney Walsh and Curtly Ambrose (West Indies) |

2000 |

|

82 |

Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie (Australia) |

2004–05 |

|

65 |

Freddie Trueman and Brian Statham (England) |

1963 |

|

61 |

Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller (Australia) |

1956–57 |

|

57 |

Kapil Dev and Manoj Prabhakar (India) |

1993–94 |

|

Other Australians: |

||

|

26 |

Craig McDermott and Merv Hughes |

1993–94 |

|

22 |

Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson |

1981–82 |

|

WASIM AND WAQAR: CRICKET’S DEADLIEST COMBO |

|||||

|

Wasim Akram |

|||||

|

|

Matches |

Wickets |

Average |

Best |

Strike-rate |

|

Tests |

104 |

414 |

23.62 |

7–119 |

54 |

|

ODIs |

356 |

502 |

23.52 |

5–15 |

36 |

|

Waqar Younis |

|||||

|

|

Matches |

Wickets |

Average |

Best |

Strike-rate |

|

Tests |

87 |

373 |

23.56 |

7–76 |

43 |

|

ODIs |

262 |

416 |

23.84 |

7–36 |

30 |

In 1989, the pair first shared the new ball in the opening Test against India at Pakistan’s cricketing capital Karachi, both taking four wickets. Among debutant Waqar’s first four was Bombay teenager Sachin Tendulkar, making his maiden appearance.

In tandem, they were to amass 476 Test wickets together, ahead even of the great West Indians Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh. In all they opened together a record 89 times. They were just as lethal in one-day cricket and if either sniffed a hint of fear from 22 yards away, they would accelerate up into another intimidating gear.

Waqar dismissed the star Indian Kris Srikkanth six times in consecutive innings and the New Zealander Mark Greatbatch eight times in eight matches. Imran Khan said he’d never known another cricketer to rise so quickly from such obscure beginnings to be among the best bowlers in the world. Waqar wasn’t as naturally gifted as Wasim, but he was more athletic and just as hungry. As he strengthened his lean frame, he bowled as fast as anyone, even the South African express Donald, known as ‘White Lightning’. And no-one, not even Wasim with his incredible late flurry at the crease, could bowl a yorker at such devastating speed. In Hobart in 1995, one of his in-swinging yorkers collected Shane Warne directly on the big toe, the resultant crack stopping him being able to bowl.

Best in short bursts, Waqar powered to his first 50 Test wickets in 10 matches and his first 100 in 20, along the way overcoming injuries, slipshod slips catching and charges of ball tampering from those unused to seeing an old ball veer in and out at speed – depending on which side was scuffed and which side wasn’t.

At Lord’s in 1992, there was a hue and a cry after England’s captain Lamb asked for the ball the Pakistanis were using to be changed. He believed it had been deliberately damaged. The world champions won by three runs, Wasim and Waqar taking five wickets between them. Nothing was proved that the Pakistanis had acted inappropriately and on the pair careered, creating devastation virtually everywhere they played.

At The Oval Test that year, Wasim took five for 8 in 22 balls on his way to nine wickets for the game. Waqar grabbed six and Pakistan won the decider by 10 wickets.

Earlier, as batsmen, they combined in a vital 46-run stand at Lord’s to allow Pakistan to narrowly win the second Test.

‘Wasim was the one who calmed me down and made me believe we could win it,’ said Waqar. Set 141 to win, Pakistan was 8–95 before Wasim (45) and Waqar (20) made the runs in a riveting final hour. It remains the closest ever Test at Lord’s.

Their most devastating Test together came against New Zealand in Hamilton in 1992–93, when Wasim took eight wickets and Waqar nine. The Kiwis were beaten in three days. Set 127 to win, the Kiwis were bowled out a second time for just 93.

Eighteen months later in Kandy, they bowled unchanged as Sri Lanka was dismissed for 71 on the first morning. Wasim took four for 32 and Waqar six for 34. Only two other pairs in the last 50 years have bowled through an innings unchanged: West Indians Ambrose and Walsh (against England, 1993–94) and Australians Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie (West Indies, 1998–99), both games at Port-of-Spain.

None of the illustrious new-ball pairs have bowled a fuller length; almost 60 per cent of Waqar’s wickets and more than 50 per cent of Wasim’s either bowled or lbw.

Unlike some of the great pairs, they were close without being great mates. Waqar was among those within Pakistan’s team unhappy with Wasim’s demanding leadership style and said so.

‘He was too young, too rash,’ he said. It tested their friendship, but both had the utmost respect for each other’s skills, Wasim backing his strike bowling with his incredible hitting.

‘He smashed the bowling. It didn’t matter who it was,’ said teammate Mushtaq Ahmed. ‘He was so incredibly talented.’

Waqar said the pressure the pair were able to build from both ends was good for both of them.

‘We got wickets for each other with some batsmen desperate to get down to the other end, away from the one of us who was making life hard for him,’ said Waqar. ‘When we were going well as a unit it was a fantastic feeling. We felt we could bowl out any side in the world. If “Was” got four wickets, I’d want to get five. It was good for the side to have such pride in our performance.’