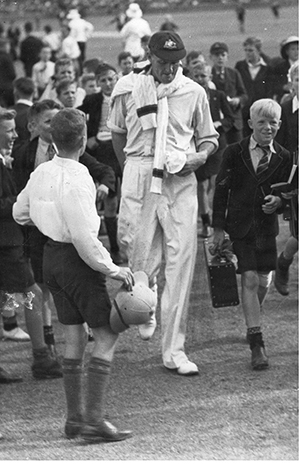

Ashes Bound: Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly leaves the WACA Ground in 1938 headed for England, without – to his lifelong regret – his long-time spin partner Clarrie ‘Grum’ Grimmett.

T

‘It was seriously dangerous out there so I took them both off. They weren’t happy with me or the limit I had imposed throughout the series. But it was cricket, not war…’

TEARAWAY TWOSOME

Clive van Ryneveld feared someone could be seriously injured. On a lively St George’s wicket and in fading light, his two tearaways, Peter Heine and Neil Adcock, had been giving the 1957–58 Australians a farewell to remember, bombarding them with short balls in a lethal display of near-Bodyline bowling. Less than 40 runs were needed with lots of wickets in hand. It was the last week of the tour and, rather than let his fired-up speedsters continue their onslaught, he withdrew them from the attack.

‘A barrage of short balls at this juncture just wasn’t appropriate,’ said van Ryneveld, one of South Africa’s most popular and versatile sportsmen known for his liking for ‘playing the game’.

‘Their bowling this night in Port Elizabeth was the most hostile I ever saw,’ he said. ‘Three short balls from Adcock went perilously close to [Colin] McDonald’s head and soon after he snicked another to [Hugh] Tayfield in the slips. [Wally] Grout and [Neil] Harvey were also peppered with rising balls and the umpire walked across to me [at mid-off], asking me to ensure that the bowlers pitched the ball up. After another over from each I switched to [the mediums of Trevor] Goddard and [off-spinner] Tayfield.

Brutal: South Africans Neil Adcock (left) and Peter Heine were as frightening a set of fast bowlers as anyone in world cricket in the mid to late 1950s.

‘Apart from the umpire having taken a hand, I had throughout the series asked Adcock and Heine to limit the number of bumpers they bowled to an average of one per eight-ball over. The incident [four years earlier] at Ellis Park against the New Zealanders, when [Bert] Sutcliffe was hit on the head by Adcock and taken to hospital, had made a considerable impression on me.

‘Batsmen didn’t have helmets. It was seriously dangerous out there so I took them both off. They weren’t happy with me or the limit I had imposed throughout the series. But it was cricket, not war. In retrospect we could legitimately have used more bouncers and maybe the series may have been closer.’

Australia’s opener McDonald was to face all the expresses of the 1950s and early 1960s from Tyson, Trueman and Statham to Hall and Chester Watson. All could be discomfortingly fast, but none were as lethal or as intimidating as Heine and Adcock on this night.

‘It was virtual Bodyline and very nasty,’ said McDonald. ‘In making four runs from the four balls I faced, I never felt closer to death!’

|

PETER HEINE IN TEST CRICKET |

|

Debut: 1955 |

|

Tests: 14 |

|

Wickets: 58 |

|

Average: 25.08 |

|

Best bowling: 6–58 v Australia, Wanderers, Johannesburg, 1957–58 |

|

5wI: 4 |

|

NEIL ADCOCK IN TEST CRICKET |

|

Debut: 1953–54 |

|

Tests: 26 |

|

Wickets: 104 |

|

Average: 21.10 |

|

Best bowling: 6–43 v Australia, Kingsmead, Durban, 1957–58 |

|

5wI: 5 |

The Australians had wanted the local umpires to invoke the law relating to unfair play, but they refused, van Ryneveld’s prompt action ensuring cooler tempers. Noted South African cricket writer and commentator Charles Fortune called it ‘the most terrifying eruption of fast bowling’ he’d ever seen.

‘The light was drab and the evening chilly. Heine and Adcock between them sent down seven overs of electrifying pace and soaring trajectory. Adcock gave McDonald three successive bumpers all of which missed him by hairsbreadths. Then both umpire and skipper van Ryneveld called for a stop to this type of attack. Adcock promptly sent down the daddy of all bumpers. From it McDonald was caught at slip.’

In the first innings the two South Africans had struck Australian batsmen six times: Jim Burke three times, and Richie Benaud, Ken Mackay and captain Ian Craig once each. McDonald finished on his back trying to avoid one Heine bouncer.

Having played two titanic series against England home and away, the South Africans were beaten 3–0 by the Australians, despite the intimidating presence of the two expresses, who accounted for 31 wickets between them.

In his memoirs van Ryneveld says they were South Africa’s all-time premier fast-bowling pair, ahead even of Mike Procter and Peter Pollock from the famous 1970 series.

‘Both were tall and very fast. Adcock [191 cm] had a beautifully fluent run-up and delivery of the ball. Heine [195 cm] was less fluent but when he got to his delivery stride he gathered his considerable strength and delivered the ball with all his might. His body language was all menace and if he managed to hit the batsman it encouraged him. He did not like to be taken off. Adcock was more accepting of being asked to take a rest.’

This was the only series in which they opposed the Australians, Adcock taking 14 wickets with his normally fuller-of-length quick in-duckers and the even more aggressive Heine, 17.

Pairing together in 12 Tests they took 95 wickets at almost eight a match, their best performance coming against England at Old Trafford in 1955 when they claimed 14 wickets in a famous three-wicket win. Both possessed the fire batsmen fear… in spades.

THE TERRIBLE TWINS

It was six months of extraordinary batting brilliance, a halcyon summer, 1947, in which ‘The Terrible Twins’, Denis Compton and Bill Edrich, excelled like no batting pair before or since.

‘First one out buys the first round,’ they’d joke to each other before plundering opposing attacks for Middlesex, England, and everyone else they represented.

In a searingly hot summer, they amassed 7355 county championship, Test and representative runs and took 100 wickets and 50 catches. Both surpassed the seemingly invincible 40-year calendar-year runs record of Tom Hayward. No pair had ever been as prolific.

‘We learned to raise our standards to the other’s needs and wishes,’ said Edrich. ‘If I was bogged down, Denis would take control. Nothing needed to be said. It just happened.’

The Terrible Twins: Denis Compton (left) with his Middlesex and England partner Bill Edrich at Lord’s.

In the post-war period of ration books, petrol coupons and general austerity, Compton and Edrich played with refreshing freedom and remarkable consistency, amassing almost 3000 runs in partnership together at an average of 100-plus. The Middlesex rooms were often in party mode as the pair invariably celebrated their centuries with champagne – and together they made 30 hundreds: Compton 18 and Edrich 12.

Five of their 11 century stands were doubles and one a memorable triple at Lord’s against the Springboks, when the pair added 370 in better than even time: Compton 208 and Edrich 189.

Their superiority that summer seemed so effortless, Compton’s zestful strokemaking including one 4 against Gloucestershire’s Tom Goddard when he’d tripped and was lying on his back. Edrich wasn’t as inventive, but he could be just as inspired. He crashed the ball even harder than his mate down the ground and through mid-on, while his explosive hook shot was compared favourably with Middlesex’s between-the-wars great, Patsy Hendren.

On the opening day of the county game against Surrey at The Oval, Middlesex made 2–537 with Edrich making 157 and Compton 137, both unbeaten. Two Saturdays later at Lord’s, they made 7–462, Compton racing to 178. So entertaining were they that on the last day of the season, John Arlott said he and many of his ‘county beat’ colleagues were reluctant to go home.

‘We didn’t want it to end,’ he said. Twenty years later Arlott released a book of the season, Indian Summer.

All season Compton and Edrich charged neck-and-neck at the run milestones, Compton reaching 1000 runs on 9 June, 2000 on 23 July, and 3000 on 27 August. Edrich’s first 1000 came on 21 June, his second on 22 July and third on 28 August. The combined run spree has never been equalled, not even by the Australian record breakers Don Bradman and Bill Ponsford in the 1930s.

|

1947 ENGLISH FIRST-CLASS AVERAGES |

||||||

|

Matches |

Innings |

Not Out |

Runs |

Highest Score |

Average |

100s |

|

Denis Compton (Middlesex and England) |

||||||

|

30 |

50 |

8 |

3816 |

246 |

90.85 |

18 |

|

Bill Edrich (Middlesex and England) |

||||||

|

30 |

52 |

8 |

3539 |

267* |

80.43 |

12 |

|

Ted Lester (Yorkshire) |

||||||

|

7 |

11 |

2 |

657 |

142 |

73.00 |

3 |

|

Cyril Washbrook (Lancashire and England) |

||||||

|

28 |

47 |

8 |

2662 |

251* |

68.25 |

11 |

|

Les Ames (Kent) |

||||||

|

22 |

42 |

7 |

2272 |

212* |

64.91 |

7 |

|

* denotes not out |

||||||

|

1947 ENGLISH TEST AVERAGES |

||||||

|

Matches |

Innings |

Not Out |

Runs |

Highest Score |

Average |

100s |

|

Bill Edrich |

||||||

|

4 |

6 |

1 |

552 |

191 |

110.40 |

2 |

|

Denis Compton |

||||||

|

5 |

8 |

0 |

753 |

208 |

94.12 |

4 |

|

Cyril Washbrook |

||||||

|

5 |

10 |

2 |

396 |

75 |

49.50 |

0 |

‘We helped each other,’ said Edrich, ‘and in between us we didn’t give the bowlers much hope… Denis was simply untouchable.’

The visiting South Africans didn’t know where to bowl to the pair. Compton helped himself to 1187 runs with six centuries and Edrich 870, with three. England won 3–0, two of the victories coming by 10 wickets.

Touring captain Alan Melville said the brilliance of ‘the twins’ had helped to make it ‘a summer to remember always…You may think we are sick and tired of Denis and his flashing bat,’ he said afterwards, ‘but he has scored with such style and good spirit that it has been almost enjoyable watching him accumulate his runs against us.’

|

DENIS COMPTON’S 100s IN 1947 |

|

|

246 |

Champion County v The Rest, The Oval |

|

208 |

England v South Africa, Lord’s |

|

178 |

Middlesex v Surrey, Lord’s |

|

168 |

Middlesex v Kent, Lord’s |

|

163 |

England v South Africa, Nottingham |

|

154 |

Middlesex v South Africa, Lord’s |

|

151 |

Middlesex v Leicestershire, Leicester |

|

139 |

Middlesex v Lancashire, Lord’s |

|

137* |

Middlesex v Surrey, Lord’s |

|

129 |

Middlesex v Essex, Lord’s |

|

115 |

England v South Africa, Manchester |

|

113 |

England v South Africa, The Oval |

|

112 |

Middlesex v Worcestershire, Lord’s |

|

110 |

Middlesex v Northants, Northampton |

|

110 |

Middlesex v Sussex, Lord’s |

|

106 |

Middlesex v Kent, Canterbury |

|

101 |

South of England v South Africa, Hastings |

|

100* |

Middlesex v Sussex, Hove |

|

* denotes not out |

|

|

BILL EDRICH’S 100s IN 1947 |

|

|

267* |

Middlesex v Northants, Northamptonshire |

|

257 |

Middlesex v Leicestershire, Leicester |

|

225 |

Middlesex v Warwickshire, Birmingham |

|

191 |

England v South Africa, Manchester |

|

189 |

England v South Africa, Lord’s |

|

180 |

Champion County v The Rest, The Oval |

|

157* |

Middlesex v Surrey, The Oval |

|

133* |

Middlesex v South Africa, Lord’s |

|

130 |

Middlesex v Kent, Canterbury |

|

106 |

Middlesex v Sussex, Lord’s |

|

102 |

Middlesex v Somerset, Lord’s |

|

102 |

Middlesex v Yorkshire, Leeds |

|

* denotes not out |

|

Jack Hobbs’ proud record of 16 centuries in a summer was beaten, as was Hayward’s monumental mark of 3518, set in 1906. The crowds were huge, an average of 10,000 at every day of every game. After years of death and deprivation, the arrival of the new season had been greeted joyously and Compton and Edrich provided rare pleasure in the opening springtime days at Lord’s.

Middlesex freewheeled to its first county championship since 1921, Compton scoring eleven 100s in 17 county matches and Edrich eight in 20. Compton averaged 96 and Edrich 77. One of their most astonishing feats came in the final half an hour at Leicestershire. Set 66 to win in 25 minutes after Compton had taken a five-for with his left-arm spinners, Walter Robins sent the twins in first and they took just seven overs to lift Middlesex to an astonishing win, with four minutes to spare. It was a massive effort, Edrich smashing 29 and Compton 33.

One of the few times Compton didn’t dominate was at Headingley in the championship game against Yorkshire, when he made just 4 and 15, much to the delight of the staunch locals who reminded him that he wasn’t a patch on local hero Len Hutton. While the golden boy missed out, Edrich scored 70 and 102 and in one new ball over from Frank Smailes started with 46440 (22).

Compton’s month of August was simply stunning: 1195 runs with seven 100s. Late that month he wrenched his knee while hitting another boundary. He was never to be the same player again.

THE TERROR AND THE FIEND

They were Australia’s first truly great opening attack: CTB ‘Charlie’ Turner and JJ ‘Jack’ Ferris. Known as ‘The Terror’ and ‘The Fiend’, the New South Wales–born pair exploited uncovered wickets expertly in the late 1880s and early 1890s, taking hundreds of wickets and on consecutive tours decimating the might of England’s finest professionals and amateurs.

Turner, right-arm, and Ferris, left, seamed and swung the ball both ways, even on the deadest of wickets in Australia. In 1888, during a particularly wet summer in England, they shared an extraordinary 534 wickets – Turner 314 at an average of 11 runs apiece, and Ferris 220 at 14. Their teammates accounted for just 129. Their amazing dominance continued on the 1890 tour with both bowlers taking 215 wickets and the rest only 164 between them.

Twice they bowled unchanged through an innings: in Sydney against England in 1886–87 – Ferris’ debut Test – and again at Lord’s in 1888.

‘CTB Turner is entitled to all the credit of a favourable comparison with the greatest bowler of this or any age,’ said cricket authority Charles Alcock after Turner’s remarkable triple-century of wickets. ‘He’s one of the keenest cricketers we’ve ever seen and the mainstay of the team from first to last. Always confident, never tiring and full of pluck; he showed himself to be a true sportsman in every way.’

In Test matches between 1886–87 in Australia and 1890 in England, Turner and Ferris gathered 105 wickets while the other Australians took only 21. Remarkably, during the zenith of Turner and Ferris’ dominance in the late 1880s, Australia won only once and lost seven times to the powerful English team. In their first Test together as a pair in Sydney in 1886–87, England was bowled out for 45 and 184 with Turner and Ferris taking 17 for 171 – yet the Australians still lost.

Ferris played eight Tests for Australia, taking 48 wickets at 14.25. He claimed five wickets in an innings on four occasions. Turner, four years his senior, was the first to 100 Test wickets, taking just 17 Tests to achieve the milestone at six a match. He took five wickets or more in an innings on 11 occasions and 10 wickets in a match twice. In 1887–88, he captured 106 wickets at 13 in just 12 first-class matches. He remains the only Australian to take 100 wickets in a home season, a record which surely cannot be beaten given the modern emphasis on three versions of the game rather than just one.

Turner attained an even greater reputation in Australia after Ferris moved to England at the height of the pair’s bowling triumphs in 1891. Unusually front-on at the point of delivery, Turner had a habit of making the ball jump sharply from a springy, graceful approach. His break-back was deadly and he also had one which seamed away from the right-handers, all at a healthy clip. The great WG Grace said Turner’s deliveries skidded off the pitch quicker than any bowler he faced, except for one man, the Yorkshireman George Freeman, reputed to be the finest bowler never to play Tests.

Turner was medium-sized at 174 cm (5 ft 8 in) and 76 kg (12 st) and for a decade, without doubt, he was the world’s most outstanding bowler, having first been discovered as a 16-year-old playing for Eighteen of Bathurst against Lord Harris’ team in 1878–79.

Three years later, in December 1881, representing Twenty-two of Bathurst against the visiting Englishmen, he accomplished the first of many great feats – seven for 33 in the first innings and ten for 36 in the second. He soon advanced into city ranks, first with Carlton and then East Sydney, where he was an immediate handful. In just seven matches in 1886–87, he captured 70 wickets, including 14–59 for New South Wales against England in Sydney. He also took a hat-trick against Victoria in Melbourne, his victims being high-profile trio GE ‘Joey’ Palmer, Tom Horan and John Trumble. For this he received a small silver memento in the shape of a stove-pipe hat, with the names of his Victorian victims suitably inscribed.

Turner’s greatest season in 1887–88, when he took more than 100 wickets, was remarkable for the fact that two teams of English cricketers toured Australia simultaneously and on behalf of different interests – one promoted by the Melbourne Cricket Club under the captaincy of Lord Hawke and later all-sportsman George Vernon, and the other under the management of regular down under visitors Alfred Shaw, Arthur Shrewsbury and James Lillywhite.

Then 25, Turner averaged almost nine wickets a match in an unprecedented run of success:

• He played twice against Victoria (for 15 wickets).

• Thrice against Vernon’s team (26).

• Six times against Shaw and Shrewsbury’s team (53).

• And once for Australia in the only Test of the summer (12).

|

CTB TURNER’S INCREDIBLE 1887–88 SEASON |

||

|

Match |

Opponent |

Figures |

|

1. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

7–107 and 0–21 |

|

2. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

4–22 and 6–13 |

|

3. |

Vernon |

7–106 and 2–40 |

|

4. |

Victoria |

5–17 and 4–97 |

|

5. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

8–39 and 8–40 |

|

6. |

Victoria |

1–79 and 5–102 |

|

7. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

1–80 and 3–19 |

|

8. |

Test match v combined England |

5–44 and 7–43 |

|

9. |

Vernon |

5–128 and 1–34 |

|

10. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

5–64 |

|

11. |

Vernon |

4–71 and 7–48 |

|

12. |

Shaw and Shrewsbury |

7–72 and 4–135 |

|

Total: 106 wickets at 13.59 |

||

In 1888 he became the first bowler to send down more than 10,000 deliveries on tour and remains among the true early icons of Australian cricket.

Ferris, from Sydney’s Belvedere club, had a lovely high action and great stamina for one so young. At 21, he was the youngest player in the Australian party of 1888. He bowled an admirable length and, according to Alcock, ‘with just enough break to deceive the batsman, he showed himself to be a bowler of unusual merit’.

Their stellar summer together on tour in 1888 saw them sweep through county and Test line-ups alike, as if they were opposing unfledged schoolboys. They bowled unchanged in matches against Middlesex at Lord’s, Derbyshire at Derby and an England XI at Stoke.

According to another noted cricket writer, Arthur Haygarth, ‘the pair created a sensation – and almost a panic – with their successes’, England losing at Lord’s before winning the remaining two Tests at The Oval and Old Trafford.

|

AUSTRALIANS TO BOWL UNCHANGED IN A COMPLETED TEST INNINGS |

|

|

Four-ball Overs |

|

|

Joey Palmer – Edwin Evans |

v England (133), Sydney, 1881–82 (Palmer 58–36–68–7 and Evans 57–32–64–3) |

|

Fred Spofforth – Joey Palmer |

v England (77), Sydney, 1884–85 (Spofforth 19,1–7–32–4 and Palmer 20–8–30–5) |

|

Charlie Turner – Jack Ferris |

v England (45), Sydney, 1886–87 (Turner 18–11–15–6 and Ferris 17,3–7–27–4) |

|

Charlie Turner – Jack Ferris |

v England (62), Lord’s, 1888 (Turner 24–8–36–5 and Ferris 23–11–26–5) |

|

Six-ball Overs |

|

|

George Giffen – Charlie Turner |

v England (9–72), Sydney, 1894–95 (Giffen 15–7–26–5 and Turner 14,1–6–33–4) |

|

Hugh Trumble – Monty Noble |

v England (61), Melbourne, 1901–02 (Trumble 8–1–38–3 and Noble 7,4–2–17–7) |

|

Monty Noble – Jack Saunders |

v England (99), Sydney, 1901–02 (Noble 24–7–54–5 and Saunders 24,1–8–43–8) |

During the 1890 tour, Ferris signed an agreement for the tenancy of a house near the Bristol County Cricket Ground and he returned to England in March 1891, having settled his business affairs in Sydney. Before leaving Australia he received a silver cigar case and match box from the Melbourne Cricket Club, which was an active promoter of tours to and from the UK late in the nineteenth century. In Sydney, Ferris was presented with a 60-guinea gold chronometer bearing his monogram on the back and an inscription on the inside: ‘Mr John J Ferris from his great admirers, 10th January 1891’.

Before his qualification with his new club Gloucestershire was completed, he visited South Africa as a member of WW Read’s 1891 English team, claiming 235 wickets. Ferris joined the elite band of cricketers to represent two countries, being selected for the only Test of the tour at Cape Town. He opened the bowling and took six for 54 and seven for 37 to spearhead his adopted country to an easy win. During this tour his figures included nine for 83 in a single innings against Eighteen of Transvaal at Johannesburg; twenty-five for 70 against Twenty-two of Border at Grahamstown; twenty-one for 62 against Eighteen of Eastern Province at Port Elizabeth, and sixteen for 70 against Twenty-two of Orange Free State at Bloemfontein.

His batting also improved immeasurably and in 1893 he scored 1056 runs with a highest score of 106 against Sussex at Hove. He began opening the batting with Dr WG Grace for both Gloucestershire and the Gentleman against the Players with success. In a club match in Bath, again with WG as his partner, Ferris made 135 not out and shared in a 352-run second-wicket stand, the Doctor making 204 not out. Ferris also represented Gloucester against the 1893 Australians.

Ferris returned to Australia in 1895 but played only three further first-class matches. He was killed in the Boer War whilst serving with the Imperial Light Horse in Durban in November 1900. He was 33.

Turner continued to be a menace to the best bats in Australia until the late 1890s. During the 1893 tour of the UK he topped the bowling averages with 160 wickets at 13.76 despite a bout of influenza which sidelined him for a stretch.

After playing two Tests in Sydney and one in Melbourne during the first great Test series in 1894–95, he was dropped from the deciding match in Melbourne, despite his status as a co-selector. He’d taken seven wickets in the previous Test, yet was replaced by an unknown named Tom McKibbin. His demotion created a sensation and was akin to Keith Miller’s Bradman-inspired initial omission from Australia’s tour of South Africa in 1949–50 and Shane Warne being dropped mid-career from the Caribbean tour in 1999. England won the Test and Turner was embittered.

But the following summer he produced one more astonishing bowling feat which he considered to be his finest. On a perfect wicket in Sydney, he took six for 35 for New South Wales against South Australia from 43.3 six-ball overs. Twenty-five were maidens.

‘Turner was on his mettle and managed to thoroughly astonish those who had relegated him to the populous realm of the has-been,’ said JC Davis, one of the leading cricket writers at the turn of the century. One of his victims was 18-year-old Adelaide prodigy Clem Hill who, in the first innings, had become the youngest cricketer to make a double century. New South Wales won the game and the Sheffield Shield.

‘The Terror’ was to claim 992 wickets at under 15 in first-class cricket to be among the top four all-time Australian wicket-takers behind Clarrie Grimmett, 1424; Ted McDonald, 1395; and George Giffen, 1022. Ferris is in the top 10 with 813 wickets at 17.52.

In 1909–10, cricket lovers in Sydney initiated a benefit match in the Terror’s honour between New South Wales and the Rest of Australia. Playing his first match in 12 years, the 47-year-old cricket coach opened the bowling and took one for 21 and made 8 and 19. The game to assist ‘the best bowler who ever lived’ raised 331 pounds.

TURNER AND FERRIS REINCARNATED

One was tall, bouncy and belligerent, the other tiny, cunning and crafty. Bill O’Reilly was the confrontationist, Clarrie Grimmett the conjurer.

Had O’Reilly been a fast bowler rather than a fast-ish leggie, his idea of the perfect wicket would have been to have hit the batsmen on the chin and watch him collapse onto his stumps. His Irish temper was forever bubbling, and batsmen were his everyday prey.

Grimmett was all about the game’s subtleties, delighting in deceiving with his round-arm leg-spinners, googlies and sliding top spinners. He shared a testimonial with his great friend Vic Richardson in Adelaide in the mid-1930s, the game set up around Don Bradman batting on Saturday afternoon in front of the biggest possible crowd. Richardson was beside himself when Grimmett dismissed the Don in the last over before lunch with a perfectly pitched leg-break which bit and spun sharply across the Don, taking his off bail.

‘That’ll teach him I can still bowl a leg-break!’ Grimmett said.

‘I suppose you know you’ve bowled us out of a thousand pounds [of gate money],’ said Richardson, shaking his head.

The New Zealand–born round-armer lived in Sydney and Melbourne before settling in Adelaide where he found an ally in Richardson, who loved his hunger for cricket and his passion to practise and improve.

Menacing: Clarrie ‘Grum’ Grimmett (left) formed a magnificent combination with Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly.

‘Before he joined us [South Australia], we thought nothing of spending two days in the field dismissing New South Wales and Victoria. Clarrie reduced that time by about half,’ said Richardson. ‘As his captain I never once had to tell him to give of his best. He gave it all the time.’

Grimmett was the first to take 200 Test wickets and in the competitive, focused, feisty O’Reilly he found the ideal partner. ‘Tiger Bill’ would bound in downwind, spinning and bouncing his leg-breaks, often at impossible-to-drive speed. His wrong-’un would often stand up, catching batsmen high on the gloves, leading to catches in the leg trap.

Together they were to mow through even the elite batting line-ups like they were Turner and Ferris reincarnated.

Grimmett’s biographer, former Australian spinner Ashley Mallett, regarded Grimmett and O’Reilly ‘as good as any pair in history’.

‘It was an odd liaison for they were direct opposites,’ said Mallett. ‘Grimmett quiet in the extreme, wheeling away diligently, almost blending with the scenery, and O’Reilly burly, robust and bellowing like a bull. He snorted and ranted. What hair he had was red and it often stood out like an Irish revolt. Together they formed the perfect spin bowling partnership.’

|

CLARRIE GRIMMETT AND BILL O’REILLY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1935–36 |

|||||||

|

Tests |

Test wickets |

Average |

Best |

5wI |

Tour wickets |

Average |

Best |

|

Clarrie Grimmett |

|||||||

|

5 |

44 |

14.59 |

7–40 |

5 |

92 |

14.80 |

7–40 |

|

Bill O’Reilly |

|||||||

|

5 |

27 |

17.03 |

5–20 |

2 |

95 |

13.56 |

8–73 |

The tandem talents of O’Reilly and Grimmett saw Australia beaten in only three of 14 Tests they played together, spread over four series. They averaged 15 wickets in each of the eight Tests Australia won. In three drawn matches they averaged 10 a Test and in the three losses five a Test – two of these being in the extraordinary summer of Bodyline. Few pairs could so expertly build and maintain pressure at both ends. There was none of the wafty extravagances of Arthur Mailey. Both hated conceding runs, the Tiger particularly.

Their signature summer was on the Veld in 1935–36, when they were responsible for almost 75 per cent of the South African wickets. Grimmett, then 44, claimed 44 wickets (at 14 runs apiece) and O’Reilly 27 (at 17). Australia won four Tests and drew the other at high-altitude Johannesburg, where both struggled to adapt to the conditions, Grimmett taking just six wickets and O’Reilly five. At Durban they shared 17 wickets and at Cape Town and Johannesburg, 15.

In the final Test in South Africa at Kingsmead, Richardson at short leg took five of the last six wickets, three catches from the bowling of Grimmett and two from O’Reilly.

So lethal were the pair that Richardson included just one specialist new-ball bowler in Ernie McCormick in the Tests, allowing Stan McCabe to bowl his mediums for a few overs at the other end before enlisting his in-form spinners. The team’s other new-ball specialist, Victorian Maurice Sievers, wasn’t included in even one of the Tests.

For the tour, the pair aggregated almost 200 wickets and delivered more than 1300 overs. No-one else took even 50 wickets.

Their most successful Ashes Test together came at Trent Bridge in 1934 when they claimed 19 of the 20 English wickets to fall: O’Reilly 11 and Grimmett eight. The Australians won with just 10 minutes to spare.

Remarkably, Grimmett never played another Test after his record series haul in South Africa, despite his average of 40 wickets a year at domestic level with South Australia. Had Grimmett, rather than Frank Ward, toured England in 1938, O’Reilly always contended that the Ashes would have been comfortably retained rather than just squared. A fall-out with the all-powerful Bradman was almost certainly the key element in his puzzling non-selection. Years later I wrote to Bradman, querying in particular Grimmett’s non-selection for the 1938 Ashes tour. Bradman replied that Grimmett, then 46, was ‘finished’.

He didn’t elaborate, but O’Reilly did, saying Grimmett had upset Bradman during a Sheffield Shield game in Melbourne when Bradman had been dismissed late in the day, just before Australia’s fastest bowler, McCormick, was about to take the second new ball. In front of his teammates, Grimmett queried the timing of Bradman’s dismissal – ‘You didn’t want to face the music, did you?’ – the clear inference that the Don was intimidated by the likely onslaught of bouncers from McCormick. Bradman was said to be angered and Grimmett, O’Reilly always believed, was the victim of one throwaway line.

‘Young Ken,’ he told me, ‘you don’t piss on statues.’

Grimmett never forgave Bradman for not including him for the tour. Instead Bradman went with Frank Ward, from his old Sydney club St George, Ward playing just one unsuccessful Test. O’Reilly termed Grimmett’s exclusion as ‘shameful’ and said his old mate carried the scars to his grave.

O’Reilly said bowling in tandem with Grimmett was always a joy and, especially early, he was pivotal in O’Reilly’s bowling success as he taught him the need for patience, accuracy, change-ups and variety.

‘We bowled together in perfect harmony,’ O’Reilly said, ‘each with a careful eye on the other. With him at the other end I knew full well that no batsman would be allowed the slightest respite. “Grum” loved to bowl into the wind which gave him the opportunity to use wind resistance as an important adjunct to his schemes.’

The pair remained the closest of friends for years and when the Test cricket came to town, they would meet up in the old open-air press box in the Mostyn-Evans Stand and saunter downstairs for a cool one or two. Until he met O’Reilly, Grimmett never touched a drink. Tiger changed all that.

TWO OLD PROS

They first opened during the ‘Victory’ tests of 1945, one a Yorkie and the other a Lancastrian. Together they became England’s finest opening pair since Hobbs and Sutcliffe.

Len Hutton and Cyril Washbrook combined in eight century partnerships in Tests, featured in three 100-plus stands in a row on tour against the powerful Australians in 1946–47, and a high of 359 against the South Africans in high-altitude Johannesburg in 1948–49. Another of their most satisfying matches came at Leeds against the mighty 1948 Australians, when they started with 168 and 129 in one of the great Ashes Tests of all.

Hutton would always take the first ball and was always so correct and assured that most others around him automatically gained in confidence. In Washbrook, Hutton saw a determined, resolute fellow Northerner, unperturbed by pace, who could bat for time as well as play shots, accelerating the run-rate as in Johannesburg when they averaged 74 runs an hour in a rare assault on the South Africans.

|

FIFTY-THREE OF THE BEST: HUTTON AND WASHBROOK IN TESTS |

||||||

|

Opponent |

Innings |

Not Outs |

Runs |

Best |

Average |

100s |

|

Australia |

21 |

0 |

1042 |

168 |

49.61 |

5 |

|

India |

5 |

1 |

200 |

81 |

50.00 |

– |

|

New Zealand |

4 |

0 |

177 |

103 |

44.25 |

1 |

|

South Africa |

19 |

2 |

1371 |

359 |

80.64 |

2 |

|

West Indies |

2 |

0 |

90 |

62 |

45.00 |

– |

|

Total |

51 |

3 |

2860 |

359 |

59.55 |

8 |

|

* The figures do not include two stands between the pair batting lower-down the list. |

||||||

‘Without question, Cyril was the best Test opening partner I had,’ said Hutton. ‘We had much in common. We had learned our cricket in similar northern surroundings. We gave each other confidence. No matter how experienced a batsman might be, he likes to have some assurance from his partner and there were times when my partners were so overcome by the occasion that they were half out before they took guard.’

Above all, Hutton liked Washbrook’s composure, even under direct fire as against the two Australian expresses Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller in back-to-back post-war Ashes campaigns, and against the slippery South African Cuan McCarthy in 1948–49. The artillery of short balls saw Washbrook regularly employ his favourite hooks and cuts. While others later in the order were daunted by the pace, he always portrayed a comforting calmness and assurance. In Brisbane, a nasty delivery from Miller reared and took his cap off, yet he was right in behind the next, competing, always the old pro.

In the second Test, in Sydney, their lightning stand of 49 was also memorable with Hutton making a quickfire 37 against a 20-minute bouncer blitz from Keith Miller, the one bowler Hutton admitted he never felt physically safe against. Washbrook had the best seat in the house that early afternoon as Hutton blazed away against Miller and Fred Freer.

‘Len dealt with them in a manner I have never seen equalled,’ said Washbrook. ‘I’m quite sure the bowlers did not know where to put the ball to him. I enjoyed myself at the other end giving him all the bowling he wanted. It was a classic knock from one of the great players of them all.’

The pair shared five century stands at first-class level that memorable summer and a sixth in a second-class fixture in Canberra when they made an Australian-high 254.

They complemented each other beautifully, Washbrook indulging himself against short bowling and Hutton, the technician, stroking the fuller-length balls through the covers. He was a master through the offside, his 364 against the 1938 Australians still the highest score by an Englishman in Tests.