Maurice Barrès [was] one of the most influential writers of contemporary France. Few young men drawn to a career in letters between the 1880s and the eve of World War I escaped his power of seduction.

—MICHEL WINOCK in Le Siècle des Intellectuels

If M. Barrès had not lived, if he had not written books, his age would be different and so would we. I don’t see any contemporary in France who has exerted, through literature, comparable or equal influence. Like Voltaire and Chateaubriand, he has created not the temporary scaffolding of a system but something more intimately bound up with our lives: a new attitude, a new cast of mind and sensibility.

—LÉON BLUM in La Revue Blanche, November 15, 1897

Friends and foes might have agreed that moral certainty was at home in Maurice Barrès, who unabashedly spoke of wanting to “educate” and “illustrate” the sensibility of his generation. The National Assembly gave him political heft after 1889 as an elected deputy from Nancy, but more important for a writer prolific even by the standards of his age was the printed page. Between the 1880s and the 1920s—throughout the would-be coup d’état of General Boulanger, the Panama Scandal, the Dreyfus Affair, the parliamentary debate over the separation of church and state, the war—he filled a hundred volumes with essays, chronicles, and fiction that expound his successive enthusiasms.

The name Barrès, which derives from the Auvergnat word for a palisaded bastion, was well suited to this man, whose exclusionary creed rooted Frenchness in the soil and bound it to the dead. It’s as if his patronymic shaped his ends. He was born eight years before the war of 1870–71, when Prussian troops overran Lorraine and occupied his native town of Charmes-sur-Moselle, fifteen miles south of Nancy. A grandfather from the Auvergne, Jean-Baptiste Barrès, who had served in Napoleon’s army, married the daughter of a tanner in Charmes, settled there, bought land, and produced one child before his young wife died. Brought up motherless, Jean-Auguste Barrès entered a loftier circle of provincial society in 1859 by marrying Claire Luxer, the daughter of a rich pharmacist. They, in turn, had two children, Anne-Marie and Auguste-Maurice.

To all appearances, Maurice’s childhood was that of a serious boy securely ensconced in a privileged little world over which the fifteenth-century Église Saint-Nicolas spread its mantle. He was taught to write by Sisters of the Christian Doctrine. He sang in the church choir. He learned his catechism. He fixed his mind every Sunday at mass on the stained-glass image of three skeletons lecturing three carefree young gentlemen. He enjoyed, albeit timidly, the ritual antics of Holy Week.1

A complement to religious instruction—salutary in several ways—was Walter Scott’s Richard Coeur de Lion en Palestine (The Talisman), all twenty-six chapters of which his mother had read to him when, at age five, he lay bedridden with typhoid fever. “At this moment,” he reminisced in his Cahiers, “my imagination seizes on several ravishing figures that will always inhabit me. The damsels, who are angels, the Orient: they slept in the depths of my mind, along with the harmony of my young mother’s voice, until reawakened during adolescence.” Other Waverley novels followed. Secretly exploring his parents’ library, he discovered books quite beyond his ken but the more pertinent for being inaccessible—Jean Cabanis’s On the Relations Between the Physical and Moral Aspects of Man, for example. Later, in correspondence with her son, Claire would recommend the articles of Jean Charcot’s student Alfred Binet.2

One of Barrès’s fondest memories was of excursions east from Charmes to the medieval ruins of Andlau and west to Sion-Vaudémont, a pilgrimage site in the Vosges Mountains, where Celts and Gallo-Romans had worshipped their gods before Christianity displaced them. Perched high above thirty other villages in a wide swath of countryside extending almost to Joan of Arc’s birthplace, it retained vestiges of the citadel demolished during the seventeenth century, when France absorbed Lorraine. For Maurice, who returned to it at every age, like an eagle to its first aerie, and wrote about it lyrically, Vaudémont would always be “la colline inspirée.”3

In childhood, those trips to the hilltop may have offered a reprieve from the mystifying inhibitions of home life. He remembered his father spending much of the day alone rolling cigarettes and reading Virgil, or playing piquet at the neighborhood café. A frail, taciturn man who collected enough rent from inherited property to employ his time as he saw fit, Auguste had few words for his family. He was kind but remote. Claire Barrès, tormented by migraines, which conjugal life did not alleviate, took to residing almost year-round among bourgeois ladies awaiting surgery or diagnosed as “neurasthenic” in a rest home at Strasbourg. Ministered to by nuns of the Soeurs de la Toussaint order, she became an absentee to her two children, though Auguste left one or the other with her for brief sojourns when he visited Strasbourg. Maurice, who never forgot the sight of wimpled sisters flitting down long corridors, sometimes said—as if in wishful thinking—that he was raised in a hospice. “I liked sorrow.”

His mother was restored to him, at the expense of his motherland, when war with Germany broke out in July 1870. All of Charmes crowded the train station under a broiling sun to cheer recruits headed for the front, many of them obviously drunk, with shouts of “On to Berlin!” Days later, the sober and the drunk lay dead en masse near towns whose names became synonymous with catastrophic defeat: Froeschwiller-Woerth, Forbach, Wissembourg. By August 10 the Germans had surrounded Strasbourg. On August 14, they entered Nancy. French soldiers trooped through Charmes hour after hour, beating a retreat in steady rain and camping wherever night overtook them. Charmésiens who had cheered them at the station a few weeks earlier now visited their muddy bivouacs. “It was an immense and squalid confusion,” wrote Barrès. Alsace and Lorraine were essentially lost after two weeks of fighting.

Compelled to supply tons of bread, rice, and meat to the German army based at the nearby village of Chamagne, Charmes had already been severely taxed when, on October 14, two battalions descended on the town with orders demanding that each landlord billet as many men as he had windows in his house. Barrès’s parents were fortunate: the quartermaster assigned them only one soldier, a Bavarian. They were additionally fortunate in not being taken hostage, having their house burned down, or suffering any of the lesser indignities meted out at random as punishment for attacks on German patrols. Not so lucky were their relatives, one of whose fingers were chopped off with a saber. During the winter of 1871–72, Maurice’s maternal grandfather, Charles Luxer, traveled on a hostage wagon to Germany, where he contracted pneumonia and died.

The Treaty of Frankfurt, whose draconian terms France formally accepted on May 10, 1871, may have worked to Maurice’s advantage. Sent out of harm’s way when Charmes was overrun, the boy came home after some months to a family more convivial for including a foreigner under its roof. In the division of Lorraine mapped out at Frankfurt, the southern Moselle valley, including Charmes and Nancy, remained French. But the treaty stipulated that French territory should continue to be occupied by imperial troops until France paid Germany the enormous ransom of 5 billion francs. It would take France more than two years to raise that sum. Until then Maurice had the company of the Bavarian, who often walked him to school in full dress.

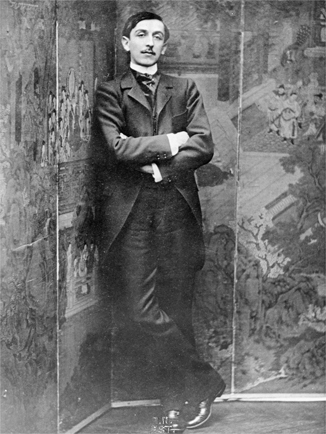

Photographs of Maurice at age eight show a miniature version of the haughty, ascetic figure Barrès cut in later years. One boyhood friend later recalled that whenever classmates ran wild he assumed a “resigned, ironical air,” opened a book, and divorced himself from the scene. Rough-and-tumble play alarmed him. But the primary school, where not much was taught or learned, had at least the virtue of being in Charmes and thus releasing him to his family every day. That arrangement changed in his eleventh year. On July 27, 1873, the German garrison paraded through town for the last time. Church bells rang jubilantly. Three months later Maurice himself left Charmes, dejectedly, to enter a Catholic boarding school at Malgranges, near Nancy.

Although parents could visit with their children every Saturday, Barrès remembered feeling cast away, and alone, in a world that discredited every reason he had ever had to love himself. The son and grandson of small-town notables now found himself snubbed. The bookish boy who, unlike his new peers, had never conjugated amare was given to understand that some knowledge of Latin separated the wheat from the chaff. And in the little gray suit chosen for him by Claire—complete with baggy knee pants, a high, starched collar, and buttoned boots—he inspired as much ridicule as Charles Bovary entering a Rouen schoolroom fresh from the countryside in yellow trousers too short to cover his blue socks. “Rambunctious kids were taken aback by his distinguished air, and made imbecilic remarks about his attire,” wrote a sympathetic witness. Worse awaited him in class. Where teachers set their pupils examples of insensitivity, one outstanding sadist hung a board around the boy’s neck listing his spelling errors. There were other incidents, all vividly remembered fifty years later. At eleven, Maurice cried himself to sleep every night in a cold dormitory room (virile discomfort à l’anglaise being the rule especially in pensions for the well-heeled) and found consolation in prayer, reciting David’s seven psalms of penitence.

The sense of being unassimilable—a pariah at worst, a Triton among the minnows at best—went deep. It pervaded all his dogmas and enthusiasms. Whether glorifying egoism in novels he wrote during the 1880s or exalting the collective unconscious thereafter, Barrès would never cease to feel isolated. At Malgranges, life became tolerable but never much more than that. The school compelled him to exchange his incongruous wardrobe for a smart blue uniform. Several boys befriended him. His mother learned, with apparent satisfaction, that he had played the part of the Virgin Mary in a play. After several years of application to Greek and Latin, he earned honorable mentions. And novels by Dumas, Hugo, Erckmann-Chatrian, and George Sand peopled his imagination with characters who made the dearth of close companionship less painful. What he couldn’t do yet, for lack of a proper model, was invent himself. “Was I to become a likeness of my schoolmates?” he wrote in his memoirs. “I couldn’t have done it even if I hadn’t been repelled by the idea. Too weak, too timid, prodigiously imaginative, desirous of another world. But what world? I had no model for what I unconsciously aspired to be. My predestined journey interested no one, was suspected by no one, neither by masters, nor my parents, nor myself.”

At the Nancy lycée, which he entered in 1877, his private syllabus came to include works reflecting not only an appetite for literary adventure but a more subtle respect for the anguish that set him apart. One can only suppose that Pascal’s Pensées, Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, and Flaubert’s Salammbô dignified his isolation, each in its own way. Did he see himself as the vexed unbeliever whom Pascal challenges to wager on God? Did the adolescent “desirous of another world” discover a kindred spirit in the author of “N’importe où hors du monde”? Did he identify with Flaubert’s lovelorn hero Matho, who, leading a revolt of mercenaries against Carthage, moves from camp to camp around the besieged citadel more like a Romantic outcast bewitched by the beauty hidden behind its walls than a generalissimo? His literary affinities all spoke of the unconsummated and the unattainable.

As well as a home for those affinities, Maurice found a mentor to help him furnish it with philosophy. During his final year of lycée he met Professor Auguste Burdeau, who, since his arrival at Nancy five years earlier from Paris’s elite École Normale Supérieure, had galvanized the school. For bright boys stifled by a faculty of timeservers, his presence was charismatic. He lectured fluently on Herbert Spencer, on Schopenhauer, on the great Hellenist Louis Ménard, on Hugo, on a hundred works outside the canonical program, but above all on Kant. The fact that the government had honored him for courage under fire during the Franco-Prussian War added luster to his erudition. Several months of Burdeau’s tutelage marked Maurice forever. “Those who did not begin their studies in the aftermath of the war will no doubt be disconcerted by the prelude to Les Déracinés,” a literary critic wrote in 1908, referring to the novel in which Barrès portrays Burdeau as Paul Bouteiller. “The fact of the matter is, however, that that generation of lycée students was fascinated by professors of philosophy. Bouteiller is not an exception; he is a type. Erudite, curious, and self-assured young masters succeeded the sober, solid Cartesians of the old regime and the somnolent Cousinians of mid-century France. They were as grave as Germans, as ardent as apostles. The vague and passionate way they had of teaching philosophy conferred upon it the seriousness of a religion.”4 Barrès himself later wrote that Burdeau was “the first superior man” he had encountered. “Well, if not superior,” he added, begrudging him the full compliment, “at any rate a man of energetic will, bent on high attainment.… He had what it took to dazzle a callow youth.”

Burdeau eventually fell victim to Maurice’s conviction that the intellectual paragon, far from enlightening his disciples, had estranged them from their vital core with Kantian universals. By 1880 Maurice was already warming to the idea popularized by Hippolyte Taine, among others, that “race” and “milieu” explained more of human truth than pure reason. Still, not everything broke when Burdeau fell. Barrès would never lose respect for the master’s ability to bend an audience to his will. He may have loved sorrow. He also loved eloquence, high pulpits, and Napoleon.

When Maurice graduated from lycée, Auguste Barrès, who stood on heights only as a tourist, insisted that his son follow a pedestrian path by studying law in Nancy and practicing it in Lorraine, where well-trained notaires were sparse.5 Maurice did as bidden, with nothing to console him but the knowledge that a friend from lycée named Stanislas de Guaita would likewise be sacrificing Paris and literature on the altar of bourgeois convention. Stanislas, who was blond, robust, extroverted, born to two aristocratic lines, and in all these respects Maurice’s foil, had bonded with him.

In law school Maurice distinguished himself almost from the first as a chronic absentee. Hours that should have been spent at stultifying lectures on the Roman code were instead devoted to reading poetry. Stanislas introduced him to Émile Zola’s Rougon-Macquart, and Zola led him to works upon which literary naturalism based its claim to scientific authority. He was omnivorous, making great meals of Michelet’s history of France, political theory, Schopenhauer (about whom Burdeau wrote), anything on Napoleon, modern fiction, physiology, Goethe, Mickiewicz, and Philip Sidney.

It wasn’t long before he moved from taking private notes to writing omnibus reviews for a local paper, Le Journal de la Meurthe et des Vosges, in which Stanislas had preceded him. Under the rubric “Échos de la Librairie,” he cast his net wide, with strategic praise for useful authors, among them Louise Ackermann, a poet whose Paris salon provided an audience for her verse. Maurice’s compliments won him an invitation, and in October 1881 he took advantage of it, hoping that Madame Ackermann would bolster his fantasies of literary elevation. She did. He chatted up Anatole France. He discussed poetry with poets whose work he knew by heart. He spied eighty-year-old Victor Hugo at the Senate library. He placed an article in a literary weekly of note (La Jeune France, to which he soon became a regular contributor). Claire Barrès, his staunch champion and close reader, rejoiced. “You were born with a caul,” she declared.6 But success only validated Maurice’s belief that a protective hood was the reward for assiduous courtship. “When one wants to arrive, when one is far from Paris and unknown, … when one has been told about the futile hours spent outside the doors of newspapers, reviews,” he wrote to Auguste Vacquerie, an old associate of Victor Hugo’s, whom he met through Louise Ackermann, “one dreams of a little word of recommendation reaching some editor on whose desk blotter one’s essay or study lies dormant.”

At the Paris Law School, Maurice did little work to good effect, cramming for examinations and passing them. Trouble didn’t really brew until his second year. He began to loathe the prospect of a professional career for which he felt no calling. It lay in the middle of the road like a coiled snake. But more acutely distressing was his competition with Stanislas de Guaita for the favors of Guaita’s mistress. All at once, Maurice suffered a humiliating rebuff and the (temporary) loss of his boon companion. Was there a connection between this betrayal and his estrangement from Professor Burdeau? Was he intent on defending an imperiled sense of self by challenging his revered teacher’s intellectual eminence and disputing Stanislas’s feminine conquest? Whatever the cause, the result was obvious. Maurice moped. Claire Barrès, convinced that his childhood bout with typhoid fever continued to undermine her son, took him to the thermal resort of Bex, in Switzerland. There, doubts about his talent joined doubts about everything else. Beset by migraines, like his mother, he wondered whether he was mad or an idiot.

But he may have been secretly resourceful. Maurice’s condition had the hallmarks of a flight into illness, with depression ultimately making the best case for suspending or abandoning the course prescribed by Auguste Barrès. Doctors agreed that his “brain cells” would need a sabbatical of six months or a year to “reform themselves.” His father, who continued to rate a secure livelihood in law above any alternative, stood firm, which meant that Maurice enjoyed no respite from his dilemma when he convalesced at home after returning from Switzerland. He prepared for law examinations to be held in November 1882, even as clandestine projects ran through his head helter-skelter: a weekly magazine, a novel inspired by his blighted love affair, a Taine-like study of the seventeenth-century poet Saint-Amant and his times, a long article on Anatole France, who had become famous with the recent publication of Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard. Maurice spent every spare moment reading. “The important thing,” he wrote to a friend named Léon Sorg, “is one’s Self. Well, I hope to perfect myself this year.” Had his friends Léon Sorg and Stanislas (with whom he had reconciled) not left Nancy for Paris, Maurice might have submitted to a schizoid arrangement, “perfecting” himself under cover of filial piety. Letters in which Léon described the greenness of intellectual and artistic pasture in the Latin Quarter was a powerful lure. Auguste Barrès would not hear talk of Paris, but what finally swayed him was a conversation with Albert Collignon, a professor of rhetoric at the Nancy lycée, whom his former student had enlisted to plead on his behalf. Father and son struck a bargain: Maurice could live in the capital with an allowance, provided he complete his law studies there.

Stanislas, Léon, and four other compatriots welcomed him at the Gare de l’Est when he arrived in January 1883.

Some years later, Barrès recalled the experience of moving to Paris through the character of Sturel in Les Déracinés. “The young king of the universe!” he wrote. “Those first days were overwhelming. He loved the cold, which pinched him into believing that this beautiful, wholly new life was not a dream. His young, fresh mouth was open to shout his happiness, and savored the air. It wasn’t Paris but solitude that possessed him. A solitude more intoxicating than love.” Like Balzac’s Lucien de Rubempré, Maurice came from the provinces with his family’s blessings and at their expense to study law, but committed to dreams of literary glory. Unlike the hero of Lost Illusions, he realized his dreams and honored the family pact.

As for solitude, Maurice may have had in mind the absence of village eyes and of judgments interfering with the accomplishment of his “new life.” Certainly there was not much solitude enjoyed or sought in Paris by the ambitious young man, who immediately reached out to writers he admired. The poet Leconte de Lisle, a leading light of the Parnassian movement, recalled that Maurice appeared at his studio unannounced on the very day he set foot in the Latin Quarter. After La Jeune France published his long essay on Anatole France, France invited him to dinner. One such event led to another, and Maurice followed every lead, like a spider hectically spinning its web around fireflies. At brasseries frequented by literati he made his presence known. It was difficult not to notice him. Lanky and elegant, dark-skinned, with a long, beaky nose, large, heavy-lidded eyes, a fringe of mustache, and a lock of black hair draped over his right temple—where it remained for the next forty years—he cut an odd figure, at once remote and nonchalantly familiar. Having very little published work to show for himself, he seemed bent on illustrating in person the Parnassian ideal of marmoreal eloquence. What struck people were his settled opinions about literature and almost everything else, pronounced in a nasal voice. Rachilde, who coedited the review Mercure de France, found him somber and conceited, “very much the prince of shadows.” Anatole France may have had something of the same impression. “Who are you, anyway?” he asked Maurice at their dinner. It isn’t known how a twenty-one-year-old in the throes of self-invention, whose smugness cloaked a multitude of demons, might have answered the question. “Why did I want Paris and the life of a writer?” he later recalled. “No very strong and clear reason, an orientation as determined as a bird’s but no reasonable reason, no clear idea of my future, not even a work plan. It was slender and invincible.… It didn’t really transcend the idea of celebrity.”

By 1884 Maurice had a diploma from the École de Droit. By 1885 he also had some literary baggage in the form of articles, chronicles, and short stories. They didn’t amount to celebrity, but they did attract some notice. Opinion lined up for and against him, seldom on neutral ground. To Juliette Adam, the editor of La Nouvelle Revue, who rejected a story entitled “Les Héroïsmes Superflus,” about the triumph of fanatical Christianity over Hellenic culture in fourth-century Alexandria, he was a precious pup captivated by the sadistic eroticism of Flaubert’s Salammbô and the erudite pageantry of La Tentation de Saint-Antoine.7 To poets he dismissed with one swipe in a review for La Minerve, he was the executioner who quipped as he killed: “I have concluded that French poetry in 1885 resembles nothing so much as a duck that keeps on running after its head has been chopped off. It no longer quacks. It has no perceptible direction. But it does run well.” The provocations that made him obnoxious to some ingratiated him with others. His prose was mannered but supple and original enough to captivate young Marcel Proust ten years later.

Impatiently waiting upon the judgment of editors, Maurice took matters into his own hands and founded a review. It was not unusual for ambitious young writers to do so in fin-de-siècle Paris. Little reviews abounded. When Maurice launched Taches d’Encre (Ink Spots) on November 5, 1884, with help from Claire Barrès, it became one of the 130 or more that lived the life of mayflies during the 1880s. Readers were warned that it would appear every month for only one year and have only one contributor—himself.

As far as its life span is concerned, his warning was excessively optimistic. The first issue contained an essay entitled “Baudelaire’s Madness,” a short story set in revolutionary times, a review defending high German culture against the animadversions of a popular Germanophobe, and miscellaneous remarks about books, authors, and literary life. The second issue contained a similar assortment. But after four monthly offerings of almost fifty pages each to a short and dwindling list of subscribers, the review ceased publication. Barrès wrote its epitaph twenty-one years later: “Raising funds, finding a publisher, recruiting subscribers, and engaging readers are a rough gauntlet. One needs energy to climb staircases all over Paris, and resilience to keep knocking on doors that slam shut! For a young man who has literary ambitions, the founding and directing of a little review is an excellent apprenticeship; it cannot fail to teach him these two essential truths: 1) that money is almost omnipotent; 2) that the literary industry is an industry of beggars.” If he was as alert as other provincials—Flaubert and Zola, for example—to the opinion of hometown readers, a report from Claire Barrès that their fellow Charmésiens took umbrage at his irreverence, his pervasive sarcasm, and especially his defense of German culture might not have displeased him. What one Parisian reviewer praised as “strange” and “sickly” in his prose and another as suavely contrarian was all that Charmes-sur-Moselle associated with big-city decadence. On the Left Bank, however, Taches d’Encre made him a more conspicuous figure.

Maurice also frequented the Right Bank, at night more often than by day, and the Butte Montmartre rather than the fashionable west end. To provincial bourgeois, nothing could have been more decadent than his nocturnal rambles. Slumming had become all the rage among toffs and adventurous young ladies of the upper class. Snobbery in this inverted form challenged its initiates to visit dangerous neighborhoods on the Butte—“apache territory”—and risk assault by hooligans or rub against the unwashed at cabarets like Le Chat Noir and subject themselves to Aristide Bruant’s musical taunts at Le Mirliton.8 Maurice, on the other hand, wanted to penetrate the tragic strangeness, as he put it, of Paris’s lower depths.

Befriending natives of the Château Rouge district comported with his excursions into the bas fonds of the human psyche. Although Maurice never met the celebrated neurologist Jean Charcot, during a visit home he witnessed hypnosis as practiced by a local pharmacist on epileptics and hysterics, of whom there was apparently no lack in Charmes. “You wouldn’t believe what I see every day,” he wrote to his friend Léon Sorg. “It’s frightening. It turns all one’s ideas about life upside down.” In Paris, where young Sigmund Freud had been a near neighbor between 1883 and 1885, Maurice attended Dr. Benjamin Ball’s lectures on morbid psychology at the Sainte-Anne asylum (founded twenty-two years earlier, under Napoleon III, to replace the city madhouse). When Le Voltaire, a prominent newspaper of the political Left, signed him up for freelance articles, he devoted his first one to the new discipline of psychiatry. It must have gratified his anxious mother, who in their correspondence had often recommended literature on disorders of the mind—Théodule Ribot’s work, for example. Ribot was a professor of experimental psychology at the Collège de France and the author of Diseases of Memory and Diseases of the Will. His magnum opus, Heredity: A Psychological Study, appeared in 1885.

Maurice may have hoped to gain from Dr. Ball’s lectures a better understanding of friends who had veered off the road they’d once traveled together into a dark woods, above all Stanislas de Guaita. It was indirectly through Maurice that Guaita met Sâr Mérodack Péladan (born Joséphin Péladan), a black-bearded occultist often seen swanning around the Latin Quarter in a velvet tunic with leg-o’-mutton sleeves, a jabot, tan gauntlets, and doeskin shoes.9 Guaita became Péladan’s disciple after embracing the idea that magic of the ancient Near East held the key to mankind’s salvation. Together they founded a school called the “Kabbalist order of the Rosicrucians.” In due course Guaita, heavily addicted to morphine (as were other of Maurice’s friends), would spend more time at the family château, applying Kabbalist exegesis to the Hebrew Bible, than in Paris.

The demise of Taches d’Encre did not leave Maurice idle. He had visited Bayreuth the year before and paid homage to Wagner, the idol of the day, in Le Journal Illustré.10 He published book reviews in Anatole France’s Les Lettres et les Arts Illustrés, a Paris chronicle in La Vie Moderne, and cultural commentary in other magazines (sometimes under the pseudonym “Oblique”) and thus eked out enough money, with his father’s allowance, to cover expenses when he left the Latin Quarter for a larger flat near Clichy, around the corner from Émile Zola’s town house.

How to become self-sufficient was the question. By 1886, Auguste Barrès had despaired of his son ever practicing notarial law. The family tried, without success, to secure him gainful employment in the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies—a clerkship of the sort that hadn’t prevented well-known writers from pouring out stories and novels after a day at the office. Maurice’s emotional state complicated matters. Though he had made a modest name for himself, it hadn’t dispelled his doubts. As fast as he ran, depression stayed hard on his heels and, whenever it caught up, robbed the seemingly impervious ironist of all self-confidence. By turns lofty and morose, the prophet of a new era and the superfluous man, he claimed to be suffering from a disease known to psychiatrists of the day as “cerebral anemia.” Others called it infirmity of purpose. The remedy for it, his family agreed, was winter in Italy.

Young Maurice Barrès in a pose and in attire appopriate to the author of Le Culte du Moi.

Maurice spent two successive winters in Italy. What he remembered most vividly of the first—besides a collection of German metaphysical studies available to guests at the hotel he occupied in Lucerne, en route to Milan—was the numbing cold. More agreeably memorable was his second voyage, in 1887. It began with a fortnight touring Venice and being enraptured by all he saw there: Tiepolos in the Accademia; canals flowing between escutcheoned walls; Palladio’s San Giorgio Maggiore; a January sun slanting over faded red facades. These conjured up Baudelaire’s image of Beauty as a “dream of stone,” and every parcel of his soul, he wrote, was “fortified, transformed.” Thinking that this aesthete’s Jerusalem might have occasioned a new birth, he left Venice happier than ever, or happy for the first time, though perhaps not noticeably so to writers he met during the next stage of his journey, in Florence. There he moved in the company of Anglo-American expatriates. A letter of recommendation from the French novelist Paul Bourget prompted Henry James to offer Barrès lunch at a restaurant on Via Tornabuoni. Through James, he met Robert Browning and Violet Paget (alias Vernon Lee), the Renaissance scholar and author of supernatural tales. He studied Italian; he read a history of the Risorgimento; he took long walks, as much for the pleasure of gazing at young Italian women as of admiring “the artistic glories of the public place”; and he wondered how much longer it would take him to find purchase in a world whose rewards he coveted. “When, then, will I be done with these slow preparations of my life?”

In one sense Maurice was the eternal initiate, toeing the margin of life while posing as an exemplar of personal authenticity. In another sense he entered the public arena with dramatic pirouettes. A year after his Italian awakening, he published Sous l’Oeil des Barbares (Under Barbarian Eyes), the first installment of a trilogy whose appeal to disaffected French youth was such that literary journalists dubbed him “prince de la jeunesse.” Barrès would soon become a name to be reckoned with.11

The title of the trilogy, Le Culte du Moi (Cult of the Self), was not only a lure but a caveat to readers expecting a plot and realistically portrayed characters. Cut from the same cloth as Taches d’Encre, the work of a sole contributor, Sous l’Oeil des Barbares follows a loner, Philippe, through mazes of abstraction and emotion from his school days (when his pariahdom begins), to Paris (where money talks and hypocrisy rules), to enlightenment, to prostration, and finally to prayer. His “rebirth” takes place when a kind of ecstatic agnosia that Barrès describes as “love of love” replaces his nebulous involvement with nameless women. At night, in a garret high above Paris, the sensible world disappears and Philippe finds himself transported by indefinable images. He has no limits. The universe penetrates him. He is all beings. “His was a virgin consciousness, a new world innocent of ends and causes, in which the myriad bonds that tie us to people and to things fall slack, and where the mundane dramas playing through our heads are merely a spectacle.”

What will happen at daybreak, Barrès asks, when his hero rejoins the “non-Self”—the world over which “barbarians” enforce their moral ascendancy? What will colleagues accustomed to seeing him strive for mediocre goals and squander himself in trivial pursuits make of his transformation? Will social commerce dull the “sublime influence” of that nocturnal trance? Will he conform? “Not at all,” writes Barrès. “This night celebrates the resurrection of his soul. He is Self. He is the passage through which ideas and images proceed solemnly. He trembles with haste. Will he live long enough to feel, think, try everything that stirs him about people moving across the centuries?”12

The question is posed by a man for whom limits are anathema, as they were for Barrès. While undoing the “myriad bonds” that make him a hostage to society, his alter ego embraces all of humanity. Rejecting the cant of barbarians, who dress themselves for the social masquerade of everyday life in “formulas rented from the reigning costumer,” Philippe resolves to name things and assign values as he sees fit.

In a preface written for a later edition, Barrès defended himself against critics who decried his anarchical skepticism:

[It’s not that we’re heroic]. Our lack of heroism is such that we would, if we could, adjust to the conventions of social life and even accept the strange lexicon in which you have defined, to your advantage, the just and the unjust, duties and merits. We have to smile, for a smile is the only thing that enables us to swallow so many toads. Soldiers, magistrates, moralists, educators—though we are powerless to swim against the current sweeping us downriver all together, … don’t expect us to take seriously the duties you prescribe and sentiments that haven’t cost you a tear.

Readers who feel at odds with the “order of the world” are assured that the only tangible reality is the Self. It is a fortress to be defended against “strangers,” against “Barbarians,” against the myth that the world outside is something more solid than a canvas for one’s imagination. But if withdrawal fosters lucidity, will it not also result in the torpor from which Philippe prays to be delivered at the end of Sous l’Oeil? Free he may be, but free for what? “It is said of the man of genius, that his work enlarges him; this is equally true of every analyst of the Self,” Barrès continues.

The modern young man suffers from lack of energy and self-ignorance.… May he learn to know himself. When he does, he will identify his genuine curiosities, he will go where instinct points and discover his truth.… He will acquire reserves of energy from this discipline and an admirable capacity to feel.

He will also acquire the ability to combine with like-minded souls. Only when the fortress of the Self has been secured can it surrender to the “man of energy” or the “man of genius,” introducing a new religion. “Indeed, we would be delighted if someone furnished us with convictions.” The narrator’s final words are addressed imploringly to the “master” who will guide him in life, “be you axiom, religion, or prince of men.”

Like those Romantics for whom “energy” was a human endowment far more consequential than reason or piety, he made the word his battle cry. Acquaintances wondered how Barrès the militant nationalist had suddenly come to supplant Barrès the aesthete. Henry James, for one, distrusted him. But in fact his nationalism followed logically from the central argument of Le Culte du Moi. It was only a matter of expanding the Self to coincide with France, of viewing France as a fortress under siege by barbarians (the non-Moi in one guise or another), and of joining the fray should history present a triumphant embodiment of the nation’s instinctual life.13

History complied. Until 1888, Barrès had been more or less unconcerned with the vicissitudes of the Third Republic. One year later, he abandoned his stance of antisocial dégagement; when a general named Boulanger emerged as a political force threatening the Republic itself, he threw in his lot with him and stood for election to the Chamber of Deputies on a Boulangist platform.

Georges Boulanger had graduated from the elite military academy of Saint-Cyr in 1857 and had risen quickly in the ranks after distinguishing himself (with serious wounds to prove it) in the colonial wars: at Robecchetto, during Napoleon III’s Italian campaign, and in the invasion launched on May 21, 1871, to recapture Paris from the Communards. By June 1880, when a liberal government amnestied surviving insurgents, Boulanger’s role in the brutal repression known as la semaine sanglante (bloody week) had largely been forgotten. Indeed, he had become a protégé of Léon Gambetta, the republican eminence chiefly responsible for legislation granting amnesty. In Boulanger Gambetta found, or thought he had found, that rarest of birds: a high-ranking cavalry officer with great panache and apparent sympathy for the common man. Gambetta did what he could (before his death in 1882) to promote Boulanger’s career. Georges Clemenceau, Boulanger’s fellow Breton, did likewise. Appointed inspector of infantry, then commander of the expeditionary force in Tunisia, Boulanger was given a ministerial portfolio in 1886 and as war minister made himself immensely popular, instituting reforms that benefited the ordinary recruit.

If Boulanger came to embody the furor Gallicae—France bold and triumphant—the occasion that engraved his popular image was the military review at Longchamp on Bastille Day 1886. He prepared for it by acquiring a magnificent black horse that showed his person and his horsemanship to great advantage. Frock-coated, top-hatted government leaders were lost in a sea of more than a hundred thousand spectators and shouts of “Vive Boulanger!” “Vive l’armée!” drowned out “Vive la République” as the general, white plumes fluttering, cantered around the racetrack. Boulanger, not the president of the Republic, was the cynosure of all eyes. And when the review ended, far more people than a police cordon could restrain mobbed their idol.

Long before this glorification, Clemenceau had begun to doubt the wisdom of fostering Boulanger’s career. “There’s something about you that appeals to the crowd,” he warned. “That’s the temptation. That’s the danger I want you to guard against.” He might as well have asked Zephyr to guard against blowing. The born actor in a star role on France’s most prominent stage could not resist playing it for all its worth. Being “offensive-minded” was his passionate motto. While it thrilled the masses, it unnerved his political confrères, and unnerved them all the more when monarchist newspapers seized upon one of Boulanger’s more provocative speeches to warn that under a republic, France was riding for another fall. In Berlin, Otto von Bismarck argued the same. “We have to fear an attack by France, though whether it will come in ten days or ten years is a question I cannot answer,” he told the Reichstag. “If Napoleon III went to war with us in 1870 chiefly because he believed that this would strengthen his power within his country, why should not such a man as General Boulanger, if he came to power, do the same?”

Boulanger’s new cognomen, General Revenge, voiced the dream of a national Second Coming. The Ligue des Patriotes, an organization whose membership dwelled fanatically on the deliverance of Alsace and Lorraine from German hands, formed up behind him. Its founder, Paul Déroulède, became Boulanger’s knight-errant. Known for his patriotic poems, his duels, and his monomaniacal oratory, Déroulède traveled the length and breadth of France beating a drum-roll of revanchism. “Throughout the whole of my journey,” he told a large crowd that gathered at the Gare du Nord to welcome him home after one tour, “the name of a single man, the name of a brave soldier, has been my touchstone. It is the name of the supreme head of our army, the name of General Boulanger!” Thanks to photogravure, images could now be turned out en masse, and the image of Boulanger swamped France. Framed chromolithographs hung in town houses and taverns and mayors’ offices. A memento industry reproduced his image on dinner plates, on pottery, as sculpted pipe bowls, on soap, on shoehorns.

This enthusiasm was by no means universal, least of all among moderates in the Chamber of Deputies, who constituted a majority. It alarmed them that Boulanger, far from being the passive object of hero worship, played to the passions he roused, and that his rich friends swayed opinion makers with well-placed largesse. They saw Boulanger’s immense popularity as a dark shadow cast upon the Republic itself. One prominent liberal, Jules Ferry, wrote to a colleague that France’s neighbors, even the most benevolent, would never trust a government inclined to look away when its chief of staff publicly flirted with civil and military demagogy: “The renown he craves, his verbal imprudences, the fantasies aired around him … have unleashed in the German press and public a bellicosity of which we should take careful note.”

Since mayhem might have resulted if Boulanger were dismissed outright, moderates devised a Machiavellian strategy. They would bring down the otherwise acceptable prime minister, René Goblet, on some extraneous issue and thus make way for a new cabinet, from which Boulanger could be excluded with relative impunity. It meant sacrificing the bathwater to get rid of an unwanted baby. And so it came to pass. Dropped from the new cabinet, Boulanger was instead made commander of the Thirteenth Army Corps, based in Clermont-Ferrand in south-central France, an assignment tantamount to exile.

His departure proved an occasion for mob protest as hysterical as the jubilation on Bastille Day one year earlier. Thousands gathered outside the Gare de Lyon. Protesters nearly unhorsed Boulanger’s carriage and gave the police all they could handle until reinforcements arrived; then gendarmes cleared a path through the crowd as the general, in civilian dress, held his top hat high for everyone to see. Inside, the police encountered thousands more, thronging the great hall, barricading platforms, standing four deep on coaches, on girders, on canopies. Scrawled across a locomotive was the newly coined slogan “Il reviendra!” But it seemed the general would never leave. At length, Boulanger, besieged in a train compartment, was hustled over to his private coach. Maniacs lying on the railroad tracks like prostrate dervishes waiting to be trodden underfoot by the Holy Litter had been removed, and the train began its run south.

While Boulanger marked time in Clermont-Ferrand, Boulangism marched forward and continued to raise alarms. Jules Ferry, who recognized the revolutionary impetus of revanchism in what was fast becoming a widespread movement, deplored its brutish character: “For some time we have been witnessing the development of a species of patriotism hitherto unknown in France. It is a noisy, despicable creed that seeks not to unify and appease but to set citizens against one another.” What distressed him was not nationalist sentiment per se but the tribal character of Boulangist nationalism, its Robespierrian exploitation of patriotic virtue, its intense xenophobia, its spurning of individual judgment and quasi-religious allegiance to a leader, its clamorous irrationalism. Where the new ethos prevailed, Montesquieu’s humanist oath—“If I knew something useful to my family but prejudicial to my country, I would endeavor to forget it; if I knew something useful to my country but harmful to Europe, or useful to Europe but harmful to the human race, I would reject it as a crime”—spelled treason. Indeed, Ferry, the consummate liberal, was, by Boulangist lights, more “foreign” than the Austrian demagogue Georg von Schönerer, whose nationalist association, the Verein der Deutschen Volkspartei, founded in 1881, had much in common with French populism. Warmongering hung a light veil over hatred of one’s bourgeois compatriots.

The conviction upon which Boulangism thrived—that France needed a hero to clean house—was greatly strengthened in September 1887 by a scandal. It began, like the play illustrating Eugène Scribe’s dictum “Great effects from small causes,” with two trollops quarreling over a dress, and it ended three months later with Jules Grévy, president of the Republic, resigning from office. What came to light that autumn was the existence of an influential ring trafficking in decorations awarded by the state. Implicated were three generals, one of whom had been financially ruined six years earlier in a bank crash. Their confessions led investigators to Daniel Wilson, a prominent deputy who resided at the Élysée Palace with his wife, President Grévy’s daughter. Wilson had used his strategic position to raise revenue for his newspapers, selling membership in the Legion of Honor to well-connected nouveaux riches who wanted their mercantile success consecrated with a ribbon or rosette.

Confusion, which had assisted Boulanger more than once, would favor him again during the parliamentary embroilment surrounding Grévy’s resignation. Among presidential candidates, Jules Ferry enjoyed an advantage in intellect and character, but Ferry was anathema to almost every party except his own, the opportunist republican faction: to the Right for having secularized institutional life, to left-wing Radicals for having expanded a colonial empire that benefited financial and industrial interests, to Boulangists for having disparaged Boulanger, and to nationalists altogether for having enjoyed excessively cordial relations with Bismarck. Moreover, intellect and character were not prerequisites for the presidency. Neither parliamentarians who wanted a figurehead nor anti-parliamentarians who wanted a savior insisted on greatness. Inoffensiveness was bound to emerge the victor from this scrum, and so it did in the person of Sadi Carnot, whose chief claim to fame was his family name. Elected president by the National Assembly on December 3, 1887, Carnot invited another reputable moderate to serve as prime minister. With the political landscape thus cleared of tall trees, a Parisian horizon opened for Boulanger.

December 1887 and January 1888 played out like the phantasmagoria of Saint Anthony’s temptations. Malcontents right and left viewed Boulanger as the charismatic partner who would dance them into power. He was a soldier, pure and simple, he insisted. But the soldier, being all things to all men, welcomed all comers. Like disparate elements of an army advancing in the dark, Bonapartists, royalists, and radical republicans pretended not to notice who their allies were, or to forget and forgive until the regime they despised had been routed by the hero they embraced.

A pivotal event in the hero’s career lay at hand. Boulanger had two self-styled impresarios, one being Count Arthur Dillon, a financier of low repute who sported a title of dubious authenticity, and the other a journalist, Georges Thiébaud, who had arranged a meeting between Boulanger and Napoleon’s nephew Jérôme Bonaparte. In February 1888, on the eve of seven by-elections, Thiébaud launched a publicity campaign urging voters to make Boulanger their write-in candidate. Fifty-five thousand people heeded him. The repercussions in Paris were immediate. Asked to explain himself, Boulanger assured General Logerot, minister of war, that his military duties occupied him to the exclusion of everything else. The secret service had meanwhile intercepted letters that proved Boulanger’s political activity. Having been unlawfully gathered, they could not be used against him, but another, admissible infraction supplied Logerot with all the evidence he needed: Boulanger had made three unauthorized trips to Paris, in disguise. Logerot suspended him from active service. On March 26, a council of inquiry took the next step and discharged him. Boulanger, who must on some level have regarded his electoral victory as a celebrity poll, was shocked.

Thus began his brief, flamboyant political career. Boulangists—Maurice Barrès among them—stood ready with a platform based on three words; their slogan, “Dissolution, révision, constituante,” signified that Parliament should be dissolved, a new assembly elected, and the constitution revised. Scarcely a week after his victory in a region he had never visited, Boulanger set out to campaign in the industrial northeast, where, three years earlier, Zola had taken notes for his great saga of proletarian hell, Germinal. The flag was waved and Parliament thrashed. “You are called upon to decide whether or not a great nation such as ours can place its confidence in callow men who imagine that suppressing defense will eliminate war,” Boulanger declared. And again: “Even Parliament is frightened by the results of its inaction. It pretends to be rousing itself but doesn’t fool anyone.… For the impotence with which the legislative assembly is afflicted, there is only one solution: dissolution of the Chamber, revision of the Constitution.”

Although Boulanger’s rhetoric was plebiscitary rather than evangelical, it made any rally a revival meeting. He addressed the abject misery of his audience but also spoke to a yearning that transcended material interests. For many people, he embodied “the Way.” Ferry had noted as much in 1887. Eight years later, the social psychologist Gustave Le Bon used Boulangism to exemplify what he called “the religious instinct” of crowds. “Today, most great soul-conquerors no longer have altars, but they still have statues or images, and the cult surrounding them is not notably different from that accorded their predecessors,” Le Bon wrote in La Psychologie des Foules. “Any study of the philosophy of history should begin with this fundamental point, that for crowds one is either a god or one is nothing.” Could anyone still believe that reason had firmly gained the upper hand of superstition? He continued:

In its endless struggle with reason, emotion has never been vanquished. To be sure, crowds will no longer put up with talk about divinity and religion, in the name of which they were held in bondage; but they have never possessed so many fetishes, and the old divinities have never had so many statues and altars raised in their honor. Those who in recent years have studied the popular movement known as Boulangism have seen with what ease the religious instinct of crowds can spring to life again. There wasn’t a country inn that didn’t possess the hero’s portrait. He was credited with the power of remedying all injustices and all evils, and thousands of men would have immolated themselves for him.

As with all popular creeds, Le Bon observed, Boulangism was shielded against contradiction by religious sentiment. It wasn’t Le Bon but Barrès who wrote, “[Boulanger’s] program is of no importance; it is in his person that one has faith. His presence touches hearts, warms them, better than any text. One wishes to let him rule because one is confident that in all circumstances he will feel as the nation does.”

Boulanger won the north handily, in what one moderate called an “inexplicable vertigo that gripped the masses and left no room for rational thought.” Now representing a populous, industrial region, he planned to take his new seat four days later, on April 10, 1888. A landau (resembling “a harlot’s carriage,” wrote the Russian ambassador) fetched him at the Hôtel du Louvre. Drawn by two magnificent bays with green-and-red cockades pinned behind their ears, it circled the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde to the acclaim of a large crowd and continued past mounted soldiers guarding the bridge. Déroulède accompanied Boulanger as far as the Palais Bourbon, where ladies had packed the gallery. At that inaugural session, Boulanger said nothing. When the prime minister declared that Parliament should postpone debate on constitutional change until time had allayed suspicions that the issue might be a monarchist snare or a cloak for dictatorship, Boulanger held fire. On April 27, three hundred acolytes, all prinked with carnations, met to celebrate their new party, the Comité Républicain de Protestation Nationale (abbreviated to Comité National), at one of Paris’s most fashionable restaurants. Presiding over them was their leader, who exhorted Frenchmen to join him in creating an “open, liberal Republic.” Opponents on the left might have responded with a version of Voltaire’s famous quip about the Holy Roman Empire, that it was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.

Maurice Barrès did not attend the celebration on April 27. He was revisiting Venice for the third time. But he raised his glass with an article entitled “M. le Général Boulanger et la Nouvelle Génération.” Boulanger’s political inauguration was a ray of hope for France, he wrote, claiming to speak for “thousands of young people stifled by vulgarity.” Savants and artists who had met the general found him not only “infinitely seductive” but keenly aware of their work, unlike the “brutally ignorant” men in power. And unlike the latter, he loved the common man. It was to be hoped that his charismatic presence would discipline the “stupid free-thinkers” who indulged their passion for intrigue and bickering in the National Assembly. Parliamentary institutions repelled Barrès. He made no secret of it.

And yet, with Boulanger’s blessing, he decided to run for office from Nancy in the fall of 1889, as the official candidate of the Comité National. “For any man of action constantly goaded by appetites,” he declared, “life is a constant state of war.” The platform on which he ran was Boulangist in its emphasis on constitutional reform, but with an anti-Semitic slant influenced by the demographics of eastern France, where many Jews resided. He was not anti-Jewish, he protested, only the advocate of countrymen being disloyally exploited. Implicitly, Jews were not countrymen but foreigners and disloyal. His first legislative campaign thus prefigured his anti-Dreyfusism.14

The odds against Barrès were steep. Even if his potential constituents, few of whom read books, had read the second novel of his trilogy, Un Homme Libre, in which Lorraine is seen to be his genetic crib, they might have regarded the tall, slim, suspiciously well-groomed twenty-seven-year-old speaking Parisian French through his nose as a carpetbagger.

Against all odds, Barrès, whose family hadn’t been able to help him secure a modest clerkship in the Chamber of Deputies five years earlier, entered the chamber as a full-fledged deputy. “The thing I relished about my adversaries was the energy of their insults. No healthier milieu. The delightful brawls of September and October! … That’s where I came to love life. Raw instinct!” he wrote. And elsewhere: “The violence of approbation and disapprobation was a tonic. I relished the instinctive pleasure of being in a herd.” Friends were astonished that someone who personified hauteur and archness could have stooped to fighting in the vulgar guise of a Boulangist. How did he reconcile his pugilism with his annual pilgrimages to Venice or the pleasure of afternoons spent in the atelier of Jacques-Émile Blanche, Paris’s foremost society portraitist?

Anatole France concluded that Barrès had perpetrated a hoax on the voters of Nancy. Others thought the same. Had they known him since childhood, however, they might have guessed that he was avenging himself on the boy who’d shied away from playground havoc. “Instinct,” “energy,” “temperament,” “animality,” “roots,” “soul,” “unconscious” became core words in the vocabulary of an ideologue at war with himself—or with the culture of which he was a particularly refined product. Interviewed soon after his election by the newspaper Le Matin, he stated that his political life would be devoted to the defense of democratic ideas and the principle of authority. “My temperament carries me in that direction. I have always celebrated the instincts, generosity, whatever else constitutes the soul of the populace. I also revere the intelligence oriented toward a leader chosen by popular instinct.”15 The larger irony was that his Kantian professor of philosophy at the Nancy lycée, Auguste Burdeau, had been elected to the Chamber of Deputies from Lyon four years earlier, and sat to the left of his proto-Fascist student.

The largest irony was that Boulanger no longer sat in the chamber and no longer resided in France. On June 4, 1888, several months after his election from the north, he had presented his brief for constitutional revision to fellow deputies. What they heard was not so much a carefully reasoned argument as a catalog of ambiguous measures. He denounced the regime in the strongest possible terms but otherwise spoke by rote, like a man going through the motions of parliamentary discourse. Openly contemptuous of him was Prime Minister Charles Floquet, who declared that young Napoleon returning from a victorious campaign had not addressed the Council of Five Hundred as haughtily as Boulanger did the Chamber of Deputies. What deeds authorized his impudence?

Undaunted, Boulanger mounted the tribune again five weeks later to demand that a stale, impotent, unrepresentative legislature be dissolved and new elections held before the World’s Fair of 1889. Once again, Floquet refuted him, mocking the pretensions to open, liberal government of a man who had spent more time in “sacristies” and “princes’ antechambers” than in republican forums.

Boulanger’s secret pact with the monarchist party, which underwrote his campaigns, did not embarrass him. He resigned his seat in high dudgeon and, declaring that his honor had been impugned, challenged Floquet to a duel.

Floquet accepted the challenge. The combatants met on July 13. No one imagined that the feisty, potbellied, bowlegged fifty-nine-year-old prime minister would gain the upper hand, but he did, and buried the point of his foil in Boulanger’s neck.

Instead of deflating Boulanger, the wound earned him political kudos. Humiliated at the hands of the bourgeois establishment as France had been humiliated at the hands of Germany, the general could still do no wrong. Five months later, a by-election to fill a Paris seat provided the springboard for his leap into the heartland of republican strength. Electioneering began in mid-January 1889. Republicans had chosen a candidate, Édouard Jacques, whose joviality made him acceptable to most factions. The posters that had littered provincial towns in Boulanger’s previous campaign now plastered the capital. To approach the Orangerie was to encounter Boulanger’s face on the flanks of the lions overlooking the Place de la Concorde. To enter the Opéra was to see his name stenciled on the steps. Boulanger stumped neighborhoods rich and poor, running with the hares and hunting with the hounds. Often accompanied by Paul Déroulède, he had the full support of the militaristic Ligue des Patriotes. To radical republicans he spoke as a radical. Catholic clergy embraced him despite the misgivings of their prelates. The Comte de Paris waffled, but royalist papers uniformly endorsed him. And indispensable to the movement was a large population of the generally disaffected.

On July 27, Boulanger garnered far more votes than Jacques. In the dead of winter, crowds chanting, “Vive Boulanger!” filled the Boulevard des Italiens, the Place de la Concorde, the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Workers who had streamed down from Montmartre joined well-groomed gentlemen from the beaux quartiers. Trumpets blared “La Marseillaise” outside the offices of L’Intransigeant while royalists at Le Gaulois prepared to toast the future restoration.

Election results reached Boulanger at Durand’s restaurant on the Place de la Madeleine, where his patroness, the immensely rich Duchesse d’Uzès, presided over one banquet table and his herald, Paul Déroulède over another. News of a landslide, the prodigal flow of champagne, thousands outside shouting, “À l’Élysée!” made thoughts of a coup d’état suddenly thinkable. Boulanger’s entourage believed that a march on the presidential palace could be accomplished without serious opposition from gendarmes, the Republican Guard, or regiments garrisoned in Paris. Déroulède urged Boulanger to wait until the morning, when his Ligue des Patriotes would have assembled twenty thousand strong at the Palais Bourbon. Boulanger himself fought shy of danger, arguing that regimes born of coups d’état died of original sin, and that in any event he stood to gain power legally six months later, at the general election. In Nancy, Maurice Barrès was jubilant.

Well acquainted with the lawyerish adages that recommended obliquity over direct confrontation, Minister of the Interior Ernest Constans, a seasoned veteran of political infighting, attacked Boulanger’s flank with a legal maneuver that justified the dissolution of the Ligue des Patriotes. Then, through agents planted in the Boulangist Comité National, Constans spread rumors that the general himself would soon be indicted on charges of plotting to subvert the legally constituted government, hoping to scare him out of France before holding a trial whose outcome he could not predict. Constans knew his man. After a brief interval, during which Boulanger’s dual privy councils—royalist here, republican there—asked themselves in feverish debate whether he would lead more effectively from exile or from prison, he arranged to flee with his mistress, Marguerite de Bonnemains. On April 1, they boarded a train at the Gare du Nord, and two hours later crossed into Belgium.

They moved from Brussels to London and finally to the isle of Jersey. Although Boulanger was reelected in absentia to the Chamber of Deputies on September 22, 1889, his party was crushed everywhere except in major cities, and he, having proved useless as a stalking horse for his royalist allies, found himself disavowed by them. “General Boulanger didn’t deceive us,” wrote one. “It was we who deceived ourselves. Boulangism is failed Bonapartism. To succeed it needs a Bonaparte, and Boulanger as Bonaparte was a figment of the popular imagination.”

During the four years he represented Nancy, Barrès, unnerved perhaps by Burdeau’s presence, seldom rose to speak or question ministers. He observed debate from his bench at the Palais Bourbon and voiced his opinions in print, as a prolific contributor to La Presse, Le Courrier de l’Est, and Le Figaro, commenting on not only political issues of the moment but literary events. While monarchists and Bonapartists who had hoped that Boulangism would answer their dreams of restoration abandoned the general, Barrès stood firm. On November 8, 1889, he joined two dozen fellow loyalists on the isle of Jersey, Boulanger’s new sanctuary, to formulate a legislative program. But toasting Boulanger in a dining hall decked with tricolor flags was their first and last collective act. After hours of equivocation, they agreed on nothing. Barrès despaired. Three days later, Boulanger issued his “Manifesto to the French Nation.” To anyone listening, it must have sounded like a voice from beyond the grave. The wraith of his party struggled on for another season, until April 1890, and breathed its last in Paris’s municipal elections.

Boulanger’s mistress, Marguerite de Bonnemains, died the following year, in Brussels. The woman whose companionship had been his refuge from the dangers and impostures of public life was now the absence that left him homeless. Sitting beside her empty deathbed and placing flowers at her tomb were the chief rituals of his day. During the last week of September 1891, he put his affairs in order. On the thirtieth he took a coach to the Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels, sat with his back against Marguerite’s tombstone, and committed suicide.

Several months before Boulanger shot himself, one of his apostates published an article in Le Figaro revealing what he knew of the general’s political, financial, and sexual transgressions. By then, Barrès had become convinced that Boulangism could not survive as a movement (or he as its representative) unless it yoked nationalist ardor to Socialist ideals. In an open letter addressing his working-class constituents, he glorified brotherhood and solidarity: “You are isolated laborers toiling in salt mines and soda-works. Grasp the hands of fellow laborers, your brothers, and despite your wretched wages and endless fatigue, you will dominate the world.” In a more public forum, Le Figaro, he confessed that he envied his forefathers who had witnessed four revolutions in half a century, and that Boulanger had blighted his hopes of witnessing a fifth before his thirtieth year. Greatly to be lamented, he wrote, was the general’s insufficient genius as a hypnotist.

1One ritual was called “Killing Pilate,” during which the choirboys, after hearing a rattle announce the end of lamentations, were permitted to run amok for a few minutes and beat each other over the head with clogs and prayer books. Another was called “Killing the Jew.” Shopkeepers or country peddlers impersonated members of the “race,” while children danced around them chanting, “Le juif errant / La corde aux dents / Le couteau et le canif / Pour couper la tête au juif!” (With rope between one’s teeth, a butcher knife in hand, and a pocket knife in reserve, to cut off the head of the wandering Jew).

2Binet wrote prolifically in the field of developmental psychology. He is famous for inventing the IQ test.

3A monument of Romanesque inspiration called “le monument Barrès” was erected in Vaudémont in 1928, with money raised by public subscription. It stands fifty feet high, on the brow of the hill.

4By Cousinians, the author, Henri Brémond (an ex-Jesuit and a friend of Barrès’s), refers to followers of Victor Cousin, who championed a philosophical system called eclecticism, the cardinal principle of which is that truth lies in the conglomeration of partial truths distilled from various philosophies. Eclecticism greatly influenced American transcendentalists and during the 1850s and ’60s became the established teaching in French lycées.

5The notaire’s domain was voluntary private civil law.

6The caul is the thin, filmy membrane, or amnion, sometimes covering a newborn’s head. It was thought to be a good omen, that the child born with one was destined for greatness.

7Barrès included it in his first novel, Sous l’Oeil des Barbares.

8Inverted snobbery took elaborate forms, one example being a costume ball at which guests, many of them titled, had to dress as characters in L’Assommoir, Zola’s novel about life in a slum neighborhood of Paris.

9On occasion Maurice himself cut an extravagant figure, sporting lilac-colored pants. But the pants didn’t fit, figuratively speaking; he came to eschew company that prized extravagance for its own sake and weary mandarins, as he described the Symbolists, who played “complicated literary games.”

10On the verge of World War I, he noted in his Cahiers: “I see how it was Wagner who dominated our youth.” Sâr Péladan appeared at Bayreuth wearing a burnoose and hoping to meet Siegfried and Winifred Wagner, but he was not granted an audience.

11Barrès owed his modest renown less to Sous l’Oeil des Barbares than to an imaginary dialogue, published in pamphlet form, with the famous author of Vie de Jésus, Ernest Renan. Readers mistook it for reportage. Renan’s son challenged Barrès to a duel for putting words in his father’s mouth. This brouhaha called attention to Sous l’Oeil and to the second volume of the trilogy, Un Homme Libre.

12The conflict between selfhood and philistine society had a chorus of voices in fin-de-siècle Europe. William Butler Yeats was thirty-six and in the throes of occultism when he noted, “The borders of our minds are ever-shifting, … and many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind, a single energy” (1901). Later, in his autobiography, he recounted his own inner flight from the world of rational barbarians. The religious myths of his childhood having been stolen from him by those “detestable” glorifiers of science, John Tyndall and Thomas Huxley, he created for himself “a new religion, almost an infallible church, of poetic tradition … passed on from generation to generation by poets and painters, with some help from philosophers and theologians.”

13Barrès still preferred to think of himself as a “cosmopolite.” In Les Taches d’Encre he declared, “We have intellectual fathers in all countries” and praised the virtue of “intellectual hospitality.” That door would close when the word “cosmopolite” became synonymous with “Jew.”

14His anti-Semitism may not have been unrelated to an abortive love affair in 1887 with Madeleine Deslandes, whose mother belonged to the wealthy Jewish banking family of Oppenheim.

15In Un Homme Libre, the sequel to Sous l’Oeil des Barbares, Philippe, after liberating his Self from society, proceeds systematically to reengage the world on his own terms. Barrès describes this exertion as “the effort of instinct to realize itself,” or as an embrace of the collective unconscious. “In expanding, the Self merges with the Unconscious, not to be swallowed up by it and disappear but to feed upon the inexhaustible forces of humanity.”