The stock market crash of 1929 shook Europe and affected the political fortunes of France’s coalition, the “Union Nationale,” which had been elected in 1926 to right a foundering ship and succeeded in doing so under the second premiership of Raymond Poincaré. In 1926, bankruptcy had became a very real prospect. Poincaré, chairing a cabinet that included six former premiers, prevailed upon the Assembly to increase revenue with higher taxes on income and property. As a result of more rigorous fiscal policing, devaluation of the overvalued franc, and German reparations payments, investors expecting bankruptcy felt reassured. Capital returned from abroad. In his person, Poincaré—whom one historian likened to an upright, unimaginative, industrious, and intelligent village notary—rallied middle-class spirits. Industrial production increased, markets opened for cheaper French goods, and unemployment fell to unprecedented levels, despite the influx of Italians and Eastern Europeans, many of whom were diverted from the United States by the American anti-immigration law of 1924. Aristide Briand, serving Poincaré as foreign minister, effected a rapprochement with the Weimar Republic (whose economic woes were alleviated in the late 1920s, thanks in large part to large loans from American banks and the financial acumen of Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, president of the Reichsbank). Briand and the German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.

With Poincaré’s retirement in 1929, after a long-lived premiership of two years and three months, deputies who had mustered behind him on bipartisan ground retreated to their factional camps. The Union Nationale collapsed. A technocrat of the Center Right, André Tardieu rose to power and fell from it three times in two years while implementing reforms championed by social progressives—a free secondary school education, social security, a Ministry of Health, rural electrification, the retooling of industry. He couldn’t count on favor outside his own party. Radicals inveighed against him for violating the separation of church and state and conferring benefits on the worker and wage earner at the expense of small entrepreneurs. The extreme Right vehemently complained that France’s security was put at risk by a government that scanted the military. When André Maginot, the minister of war, addressed the Assembly, L’Action Française declared that Tardieu’s government had learned nothing from the bloodiest war in history. “This government devoid of memory, devoid of conscience, devoid of reason, this inhuman government exposes us today to the prospect of waging again what M. Maginot called the war of bare chests, exactly as in 1914, after fifteen years of credits for new matériel being sabotaged, according to the dictates of the Dreyfus party!” Funds were voted to build a line of fortifications along the German border, the so-called Maginot Line.

By 1932 everything was scarce as the world financial crisis visited increasing misery upon France. England’s renunciation of the gold standard in 1931 dealt a severe blow to the French economy, which had been buffered from the initial effects of the Depression by its enormous gold reserves and budget surplus. Prices plunged, and the agricultural sector suffered from the collapse even more grievously than the industrial. Hundreds of thousands were thrown out of work. Government revenue fell by a third. In Parliament, Left and Right ganged up on the ruling center, which retained control, but with a shaky hand. Between November 1929 and May 1932, eight governments lost confidence votes. None lasted more than a few months. Tardieu and Pierre Laval served as premier three times each, while in Germany, where over four million were unemployed, Hitler moved inexorably toward the chancellorship.1

Each served for the last time in 1932, before the general elections returned a majority of left-wing candidates, divided, as in the previous decade, between minority Socialists and majority Radicals. Their failure to deal with the economic crisis soon became apparent. Men and women staged hunger marches all over France. Radicals wanting civil servants to accept a cut in salary despite protests, and Socialists exciting the Radicals’ fear of big government by demanding the nationalization of major industries were two of the bones they worried. Reparation payments ceased for good when Hitler came to power and deficits soared. With parliamentary democracy at its most dysfunctional, premiers rose and fell, pursuing no line of policy, and cabinet ministers shuffled around in the same game of musical chairs played by their conservative brethren.2 These cabinets were sometimes dubbed “corpse cabinets” by the disillusioned public, consisting as they did of men revived from a fallen administration.

Word spread of German rearmament, but the French budget expressed no urgent need to modernize the army. Nor was Germany called to account. “The history of Europe and of European confabulations in recent weeks may be resumed with three points,” wrote Charles Maurras in the October 13, 1932, issue of L’Action Française. “Firstly, it is admitted that Germany has rearmed. This is a truth … to which no one can raise the least objection, not even our good friends the English, who claim to be as well informed as the French, with their classified and unclassified dossiers. Secondly, no one in Europe can deny that German rearmament flouts treaty law. Thirdly, since no one wishes or dares to repress this violation, we concluded that everyone is of the opinion that the law should be changed. Whenever something similar occurs in the civil domain, one calls it an encouragement of crime.… We recommend that the professor of literature Herriot, who … knows Pascal inside out, consider his famous reflections about the might that makes right and the might that serves justice. It will furnish him with the theme for yet another oratorical topos. As far as action is concerned, the book on him is closed.”3 Maurras made much of this admonition in a 120-page plea at his trial for treason in 1945. It was outweighed on the scales of justice in postwar France by his multitude of tirades against Jews and the Republic.

Maurras’s trenchant article did not sit well with Herriot, who lost the premiership two months later, but reprimands in L’Action Française did not speak as loudly in 1932 as they had a decade earlier. The favor that Maurras, his movement, and his paper had officially enjoyed in Vatican circles did not extend beyond Pius X’s papacy.4 Pius’s successors, who strove to promote world peace, distanced themselves from an ideology whose basic premise was that ends justified means and that all means should be employed to the ultimate end of restoring a monarchy. Maurras’s nationalisme intégral, which regarded the nation as the sovereign to which individual scruples rendered obeisance and as a higher moral authority than the Holy See, appalled Pius XI. It had also lost the hold it had once had over the French episcopate when, during the Dreyfus Affair, many of its prelates had succumbed to the passion that made bedfellows of the church and the anti-republican Right. In August 1926, Cardinal Andrieu, archbishop of Bordeaux, reproached L’Action Française for being Catholic by design rather than conviction and for bending Catholicism to its political agenda instead of serving the church’s mission on earth. Cardinal Andrieu’s article and further admonitions in the official Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, heralded an apostolic decree. It came in December, when seven of Maurras’s works and L’Action Française (guilty of defending itself against ecclesiastical opprobrium in vitriolic articles signed by Maurras and Daudet) were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. Penalties followed. On March 8, 1927, the Apostolic Penitentiary declared that seminarians loyal to L’Action Française would be deemed unfit for the priesthood; that priests guilty of the same offense would be prohibited from exercising their sacerdotal functions; and that parishioners who continued to read L’Action Française would be stigmatized as public sinners and denied the sacraments. To a French Catholic novelist named Henry Bordeaux, Pius XI said of Maurras, “He is one of the best brains of our times; no one knows that better than I. But he is only a brain.… Reason does not suffice and never has. Christ is foreign to him. He sees the church from the outside, not from within.” L’Action Française refuted the papal decree in an article entitled “Non Possumus.” “The reigning pope,” it stated, “is not invulnerable to human error where political questions are concerned, and though the church has the power to promise eternal life, men of the church—all of history proves it—can be led astray by dishonest parties, can engage in harmful enterprises. L’Action Française is not a Catholic paper. It was not founded by any specifically Catholic authority; it founded itself.”

The papal decree hurt the movement, although a distinguished Catholic thinker, Jacques Maritain, could still note early in 1927 that “without having a single one of its members in Parliament, L’Action Française enjoys among many the prestige of a virtual public authority or principate of opinion.” Soon thereafter, circulation of the newspaper began to fall. Many provincial chapters languished. Moving its headquarters in Paris from the Rue de Rome to a building on the elegant Avenue Montaigne belied the fact that its coffers were empty, or would have been if not for patronage from rich aristocratic families.

The number of Camelots du Roi, for whom the sacraments were a trifling consideration, may not have dwindled significantly, but under the conservative governments of 1926–32 they tended to make their presence felt with pranks rather than acts of brutal incivility. The most sensational event took place in May 1927 and involved Léon Daudet, who barricaded himself inside the offices of L’Action Française, behind barbed wire and barred gates, when summoned to serve the prison term imposed on him two years earlier for slandering the cab driver in whose taxi his son Philippe had shot himself. The siege lasted three days. Jean Chiappe, a prefect of police known for his right-wing sympathies, finally prevailed upon Daudet to surrender. He emerged with his praetorian guard of Camelots and was driven in Chiappe’s limousine to the Santé Prison, where he endured several weeks of comfortable internment. On June 25, a colleague impersonating an official of the Ministry of the Interior informed the warden that the government, in a gesture of conciliation to extremist parties, wanted Daudet and a Communist leader released immediately. The gullible warden complied. Daudet walked, and slipped across the border into Belgium. He was eventually pardoned by President Gaston Doumergue.

The Camelots du Roi truly sprang to life with demonstrations in February 1931, when the Ambigu theater staged the French adaptation of a German play about the Dreyfus Affair. Intent on shutting it down, they disrupted performances with stink bombs and challenged patrons entering the theater with their heavy canes. Scuffles on the Boulevard Saint-Martin became bloody riots. Shouts of “Long live the army” and “Down with the Jews” revived memories of the furious reaction to Zola’s “J’accuse” in 1898. Havoc reigned nightly between the Porte Saint-Denis and the Place de la République for almost three weeks, until performances of L’Affaire Dreyfus were suspended by Chiappe, who acceded to a request by the directors of a veterans’ association called the Ligue des Croix de Feu that an end be put to the “lamentable exhibition” in whatever way his “professional conscience” dictated.5 L’Action Française published the letter and added, “All good Frenchmen will congratulate the Croix de Feu for having expressed, with the dignity befitting an association that incorporates glorious veterans of every opinion, its indignation at a national spectacle that has lasted too long. We know that other associations of veterans are preparing to intervene.”6 It characterized L’Affaire Dreyfus as a piece of “German and anti-French propaganda” whose audiences in Berlin mocked the French uniform. Le Populaire, a daily, compared the success of the Camelots du Roi and the Croix de Feu in suppressing a play about Dreyfus to that of the “Hitlerians” in having the film adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front withdrawn from German cinemas. “In both countries, the same individuals, animated by the same spirit, pursuing the same goals by the same means, terrorize assemblies and the streets with organized bands. The League of the Rights of Man insists that republican opinion accustom itself to the danger of this nascent Fascism, which is all the graver for going unopposed by the feeble powers that be.”

Although the rioters on this occasion were mainly Camelots du Roi, Paris abounded in right-wing “leagues” with paramilitary contingents always ready to parade and brawl. Their numbers increased exponentially in the early 1930s, when the Cartel des Gauches, resuming its fractious career, implemented deflationary measures that made a weak economy weaker. Most numerous were the Union Fédérale des Combattants and the Union Nationale des Combattants. Best known was the aforementioned Croix de Feu, an association of decorated veterans whose membership included general volunteers pledged to the movement’s central tenet, that the “spirit of the trenches” should engender “national reconciliation.” Its motto was “Travail, famille, patrie” (later adopted by the Vichy regime). Everything that caused division, above all class conflict, was objectionable to its leader, Colonel François de La Rocque, who, if judged only by the movement’s torchlight parades and military maneuvers, might have passed for a Gallic Hitler. An older generation may also have been reminded of General Georges Boulanger. The colonel did indeed express his repugnance for party politics and internationalist creeds, but, whatever his nebulous language may have shrouded, nothing in it suggests a Fascist alternative to the Republic. Nor did anti-Semitism strongly color his understanding of France’s fall from grace.

The same cannot be said of many among his four hundred thousand followers. And passionate anti-Semites had a choice of aggressively bigoted organizations. One of the largest in the early 1930s was Solidarité Française. Financed by the vastly rich perfume manufacturer François Coty, who acquired Le Figaro after the war, it proposed to exorcize the demons of parliamentarianism, of rampant bureaucracy, of hospitality to foreigners, of modern art, of Bolshevism, and of the “anonymous, irresponsible, vagabond capitalism” more or less synonymous with international Jewry. Like other such groups, notably “Les Francistes,” whose model was Mussolini, it conferred honor and pride upon its members. Also modeled after Mussolini’s Blackshirts were the Jeunesses Patriotes, largely recruited from among university students and financed by Pierre Taittinger of the Taittinger champagne house. They wore berets and blue raincoats. They gave Roman salutes.7

What sparked this explosion early in 1934 against the Third Republic was a scandal involving financial skulduggery and political corruption called the Stavisky Affair.

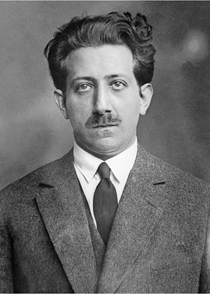

Alexandre Stavisky was the son of Emmanuel Stavisky, a Russian Jewish immigrant. Alexandre received his formal education at the Lycée Condorcet, but by 1912, at twenty-six, he was well on his way to establishing himself as an inveterate swindler. That year, he rented the Folies-Marigny Theater for a summer, staged a play that closed after two weeks, and failed to repay concessionaires their surety deposits. He was brought to book but never tried, thanks to the outbreak of World War I. The war also saved him from prosecution for swindling the munitions firm Darracq de Suresnes of 416,000 francs in the sale of twenty thousand bombs to the Italian government.

Amnestied in 1918, Stavisky took up where he had left off, with ever more ingenious scams, for one of which he served seventeen months in prison. He was by no means alone in robbing French investors during the 1920s. Almost as infamous as he, were Marthe Hanau and her former spouse, Lazare Bloch, who founded a financial journal that drummed up business for shell companies it promoted and fraudulent short-term bonds promising high rates of interest. Brokers drove a thriving trade until banks, at the instigation of a rival financial news agency, looked into the matter more closely. Hanau distributed bribes to quash rumors. But in December 1928, police arrested her, Bloch, and their business partners. Investors had lost millions. Hanau delayed the trial by staging a hunger strike, rappelling down a hospital wall on a rope of sheets to escape being forcibly fed, and resorting to other extremities. When the trial finally took place, in February 1932, she revealed the names of complicit politicians. Freed from prison after nine months, she published an article about the shady side of the financial markets, quoting classified material leaked to her by an employee in the Ministry of Finance. For this indiscretion she went back to prison. She escaped, was recaptured, and, at her wits’ end, committed suicide. “The founder of the Gazette du Franc, who could take pride in her exalted and useful republican collaborations,” L’Action Française gloated, “was 49 years old, which is to say that she was barely 40 when she conceived one of the most formidable hoaxes of our time.”8

No less devious was Stavisky, who entered the 1930s in the shadow of a trial adjourned nineteen times, but mingling prominently in café society, gambling for high stakes, and sporting the accouterments of wealth.9 He and his glamorous wife occupied rooms at the Hôtel Claridge. A compulsive illusionist whose main act was the Ponzi scheme (performed under the alias Serge Alexandre or Monsieur Alexandre), he owned two newspapers (of opposite political persuasions), a theater, an advertising agency, a stable of racehorses, and a sty for enablers feeding at his trough. The latter were highly placed policemen, rogue politicians, disgruntled civil servants, crooked lawyers, publicists, and influential journalists. In 1931, undeterred by omens, Stavisky launched the operation that eventually made him the titular villain of an “affair.” For quite some time he had had an eye fixed on municipal pawnshops, or crédits municipaux, which were in fact lending institutions recognized by the government as “publicly useful” and authorized to issue tax-free bonds, with the understanding that profits derived therefrom would benefit the municipality. In a fateful meeting at Biarritz, Stavisky inveigled the mayor of Bayonne, who was also a well-connected legislator, into securing the approval of the relevant ministry for a crédit municipal. It served their purpose that Bayonne lies twenty-five miles from the Spanish border. “The month Spain lost its king, April 1931, Bayonne gained its crédit municipal,” writes the historian Paul Jankowski. “Revolution in Madrid had come just in time for Stavisky and his hirelings, and had made plausible their fable—of jewels from Alfonso XIII and the royal family, from Countess San Carlo, from rich Antonio Valenti of Barcelona, and from frightened Spaniards reported crossing the border to seek safe haven for themselves or their valuables. Rumors of plunder and flight justified by their proximity to the town’s new crédit municipal, launched with a budget that would have been extravagant even in a teeming metropolis.” This ur-fable laid a foundation for every subsequent ruse, the success of which depended upon connivance, nonchalance, false assumptions, a double set of books, and the flight of common sense. How Bayonne’s crédit municipal could afford to pay high interest rates in a depressed economy and for what purpose it needed huge sums were questions that bondholders didn’t pose insistently enough, or at all. It swelled like the frog with delusions of grandeur bloating itself in La Fontaine’s fable. Large insurance companies flattered the frog’s wish to pass for an ox. La Confiance, L’Avenir Familial, and others poured millions into Stavisky’s magic show.10 Stavisky himself pocketed 160 million francs.

The frog burst in 1933, when an insurance company sought to redeem its fake bonds. The crédit municipal temporized as Stavisky, having made no provision for the inevitable, frantically rallied cronies to raise funds with a new bond issue. Things did not go his way. Rumors of malfeasance were spread by journalists who delved deeper than government overseers. While the latter continued to shuffle paper from ministry to ministry, a serious investigation was set in motion. The treasury receiver in Bayonne scrutinized the crédit municipal’s books on orders from the state comptroller, and revealed a breathtaking discrepancy between its private records and its public fiction. It had nothing very valuable in pawn, least of all the Spanish crown jewels. Police officers arrested a key executive of the bogus enterprise, one Gustave Tissier. It was December. Everything then began to unravel.

Beneficiaries of pension funds heavily invested in the crédit municipal (with the Ministry of Labor’s approval) derived some satisfaction from seeing Stavisky exposed. They would learn long after the fact that the normally suave con artist had lost his composure upon hearing of Tissier’s arrest and had fled south to the French Alps. The hunt soon began for the man known in many quarters as M. Alexandre. Reporters caught wind of it and finally bruited his surname. On January 1, 1934, Paris-Soir ran an article entitled “Search Continues for Swindler Stavisky.” Several days later, the criminal investigation department—Sûreté Générale—received a credible tip. Inspector Marcel Charpentier boarded a train for Lyon and on January 8 met with the owner of a chalet perched on a snowy slope of Mont Blanc in Chamonix. Police entered, knocked on the door of a back room, identified themselves, heard a shot, and found Stavisky mortally wounded. Officialdom ruled it a suicide, leaving half the country convinced that people in high places against whom Stavisky could have testified were assassins.

Blame for the impunity with which Alexandre Stavisky had conducted his criminal operations fell on many heads as the prosecutor’s office interrogated a host of witting and unwitting accomplices in government, in the Sûreté Générale, in the judiciary, in the press. Camille Chautemps, France’s most recent prime minister, a Radical whose party had much to answer for, promised that neither fear nor favor would sway the hand of justice. The skillful orator acknowledged the lapses of justice (the nineteen adjournments of Stavisky’s trial) and of the police, wrote a sardonic commentator in Le Figaro: “And this rapturous beating of mea culpas on other people’s breasts was punctuated by an oath to exact punishment, once the inquests are complete, without regard for bonds of friendship, affection, or family.… The Left seemed to consider this promise a gesture worthy of Brutus.” One of the first casualties was the minister of colonies, Albert Dalimier, who, as minister of justice in 1932, had declared Bayonne’s crédit municipal a legitimate candidate for the investment of insurance funds. Dalimier resigned when his letter of authorization was leaked to the press. Leaks led to resignations, detainments, and suicides. Thirteen months after the inquest began, the investigating magistrate gave the public prosecutor two volumes containing seven thousand pages of experts’ reports. By then Chautemps had long since fallen from power. Nineteen of Stavisky’s associates, as well as his wife, Arlette, were indicted for crimes and misdemeanors.

Stavisky’s widow, Arlette, formerly a Chanel model, being tried in 1936 on a charge of colluding in her husband’s swindles. She was acquitted.

News other than the Stavisky Affair was forced into cramped quarters. Many daily papers regularly reserved half of the front page for analyses of the nefarious scheme, photographs of the actors, and commentaries suggesting that it would not suffice to chase moneylenders from the temple: the temple itself had to be demolished. Like Dreyfus’s treason, Stavisky’s machinations told against the Republic. In an article about the Dutch Communist beheaded by the Nazis for burning down the Reichstag, Philippe Barrès, Maurice’s son, wrote that a dynamic team was needed in France, as existed in Germany, to purge the homeland and make it stand tall in the eyes of the world.11 “While we blame the harshness of the National regime, it is high time that we react to some of the same disorders that afflict the Reich.… We must proceed to investigate the Stavisky scandal exhaustively.” The Far Left and the Far Right chanted antiphonies of denunciation. Could anyone doubt any longer the turpitude of the ruling class? asked L’Humanité. It was pervasive. “Every day a new name, a new agency of government, a sacred principle of bourgeois democracy is sucked into the whirlwind. Magistrates shielding a swindler. Deputies serving him. High functionaries sharing his booty. A police force of gangsters admitting him into their midst, then shooting him. A minister handing pension funds over to him.… Liberal? Conservative? Your alternate displays of morality are nothing but the dustups of rival gangs.” Léon Daudet, home from Belgium, hectored the “government of Scum” day after day, surpassing himself in invective. Charles Maurras took the broader view: “Besides the Jewish State, the Masonic State, the immigrant State, the Protestant State, there are several thousand profiteering clans whose titles derive from their yeomen work in dismantling the French State after 1793.” The battle between parliamentary conservatives and liberals over Stavisky was, he declared, nothing but a preliminary skirmish in the war between the “legal State” constituted by usurpers and the “real State” of true Frenchmen taking up arms against a “judiciary of bandits, a police force of assassins, a government of traitors.”

To militant anti-republicans, and particularly to L’Action Française, the Stavisky Affair was revivifying. Its leaders lived for havoc even as they called for the restitution of true social order, and on January 10, a day after several hundred demonstrators, mostly Camelots du Roi and their cousins in the Jeunesses Patriotes, had been repulsed by the Republican Guard near Parliament, they rallied the faithful to gather in greater numbers. “Parisians! This evening, upon leaving your offices and ateliers, when cabinet ministers addressing venal deputies try to hoodwink the French, come shout your scorn for their lies.” More than five thousand people heeded the call. In the tradition of Parisian firebrands, they halted traffic near the Palais Bourbon with cast-iron grates, overturned lampposts, and tree branches. Deputies inside Parliament heard shouts of “Down with the sellouts!” coming from the streets. After six hours of confusion, paddy wagons were filled to overflowing. Thirty policemen suffered injuries.

The government suspended performances of Coriolanus at the Comédie Française, fearing that Shakespeare’s play about a patrician hero pitted against Rome’s plebeian tribunate might incite further violence. To no avail. Things went from bad to worse. In his paper La Victoire, Gustave Hervé, a right-wing extremist, who was beating the drums for Pétain, declared, “Anything but this filthy anarchy! How many people must be mumbling between their teeth these days: ‘Ah! Vive Mussolini et vive Hitler!’ ”

Ginned up by the right-wing press, bolstered by paramilitary leagues, and confident that the prefect of police, Jean Chiappe, would refrain from turning water cannons on Camelots du Roi as he did on Communists, L’Action Française grew bolder. No longer content to win minor victories in peripheral neighborhoods, it concerted with the Union Nationale des Combattants and the Jeunesses Patriotes to launch a demonstration from the Place de l’Opéra on January 27. Thousands gathered there in the early evening and swarmed down lamplit streets and avenues leading to the Place de la Concorde, where, within sight of the National Assembly across the Seine, large police vans blocked their advance. The rally became a riot. It lasted until midnight. By that time Chautemps had resigned from office, citing the riots as one reason for his resignation. There were violent clashes at barricades. Police had taken the precaution of having tree grates removed, but the rioters set fires, cut fire hoses, overturned kiosks and benches, ripped up gas lines, smashed shopwindows. Three hundred people were arrested, all of whom soon walked free. Later, a commission of inquiry concluded that “these systematic depredations, the street turmoil, the paralysis of traffic cost the authorities their prestige and exposed the pusillanimity of justice. It paved the way to February 6.” Among those wounded on January 27, no one died. Blood would flow ten days later.

High on the agenda of the new premier, Édouard Daladier, was the reform of a police department responsible for allowing Stavisky to operate without let or hindrance, and particularly the removal of Jean Chiappe, who, after years at the prefecture, considered it his fiefdom. Daladier offered the dapper, well-connected, right-wing Corsican a prestigious sop—the governorship of Morocco—lest his eviction appear to have been dictated by Socialists in the coalition, or by hints of involvement in the Stavisky scandal (an investigative report having indicated that the Prefecture of Police had been for some time well aware of Stavisky’s mischief and done nothing about it). News of the ministerial shuffle and of Chiappe’s rage were a spark to tinder. The paramilitary leagues, loosely confederated, set in motion plans for a monster demonstration. On February 4, they distributed a tract declaring that the country was in danger; that all signs pointed to a “formidable purge in the army, the judiciary, every level of administration”; that the people had to impose their will. Was it not true that the government had equipped the Palais Bourbon with machine guns? (It hadn’t.) In the February 4 issue of L’Action Française, Charles Maurras wrote:

The thieves have one enemy and even two: Paris and France. The sustained, repeated demonstrations in Paris … testify that our race, sound and upright, will not suffer the crimes of highway robbers, however highly placed, to go unpunished. The cabinet deploys against France like a battalion of Germans. They have taken the police chief hostage.

In an article he had written for the London Evening Standard, Léon Daudet declared that the day was fast approaching when the Republic and parliamentarianism could no longer pillage France. His colleague Maurice Pujo called upon Parisians, when summoned, to “shake the Masonic yoke” and topple “this abject regime.”12

The editors of L’Action Française issued that summons two days later, on February 6, 1934, the day of Premier Daladier’s scheduled appearance before Parliament. Another such summons came from Solidarité Française, whose secretary-general warned compatriots that they were being herded to the “fair,” like animals branded for sale or slaughter, by politicians “sporting names as un-French as Léon Blum.”

He urged that members should demonstrate that evening against “this travesty of a regime.” They were to gather on the boulevards between Richelieu-Drouot and the Opéra, and to march “at precisely 7:15.”

At the Sorbonne, flyers announced a political epiphany: “The long awaited hour has arrived! The hour of the national Revolution! Everybody, show up on the Boulevard Saint-Michel at 6 o’clock.” Not to be left behind by events but wary of violence, the Croix de Feu mustered some of its men on the Right Bank at a prudent distance from the Place de la Concorde, where Camelots du Roi and others would challenge police assigned to defend that approach to Parliament, across the river. Eventually many broke ranks and joined a mob flooding the Place de la Concorde from the Rue Royale and other tributaries.

By six-thirty, after sunset, the battle was joined. Buses were burning on the great square, near the obelisk and the American embassy. Fires had been set elsewhere. Several hundred gendarmes, mounted gardes républicaines, and detachments of riot police called up from the provinces earlier that day faced a mob of thirty thousand, some armed with guns and razor-tipped sticks to hobble the horses, but many more with weapons of opportunity: chunks of asphalt, stones, hoops torn from the Tuileries Garden, the tree grates removed ten days earlier but since restored.

Rioters and police charged and retreated by turns, while parliamentarians hurled brickbats at one another in the Palais Bourbon (which was being immediately threatened by Camelots du Roi and three thousand members of the Croix de Feu who had begun their rally on the Left Bank in the Faubourg Saint-Germain). Daladier attempted to conduct parliamentary business, citing such critical issues as the industrial and agricultural slump, high unemployment, threatened savings accounts, and national security in a Europe overshadowed by belligerent dictators. “Scandals pass, problems remain,” he noted. “We shall defend the regime. Republicans must unite if they want to ensure the survival of one of the very few free political arenas left in the world.” Likewise, Léon Blum, the leader of the Socialists, exhorted the opposition to repudiate the campaign discrediting institutions and to appreciate the danger of prolonged debate. Neither Daladier nor Blum could make himself heard above the commotion. Taunts came from Right and Left. A member of Daladier’s own Radical Party rose to criticize him for his “insolent refusal” to address the Stavisky Affair, saying, “He invokes preoccupations that weigh heavily on all of us and the need for public order, but he is the first to threaten public order. The premier willingly speaks of Fascism, but the day the executive power forbids the sovereign Assembly to deliberate is the birthday of Fascism.” Maurice Thorez, leader of the French Communist Party, denounced Daladier as a “Jacobin dictator.” It was the responsibility of proletarians, he said, “to chase Fascist bands from the streets” and to take arms against men who defended a “financial republic” corrupted by venal charlatans. Debate, such as it was, stopped when the Communist delegation began to sing “The Internationale,” prompting other deputies to answer with “La Marseillaise.” By then, reports of gunfire on the Place de la Concorde and of people fatally wounded had reached the Assembly.

Guests observing the insurrection from the balcony of the palatial Crillon Hotel saw gendarmes beset at a dozen different points by demonstrators hurling torches and spreading lumps of coal over the cobblestones wherever mounted police threatened to charge. Next to the Crillon, flames shot out of the Naval Ministry. Across the square, a fusillade was heard on the riverside approach to the key bridge, the Pont de la Concorde. While reinforcements cleared the Tuileries Garden, bordering the east end, a large column of veterans—five or six thousand men singing “La Marseillaise”—entered from the west, via the Champs-Élysées.13 Prominent as well were members of the Union Nationale des Combattants, veterans easily recognized by their battle ribbons and Basque berets. Repeated attempts were made to breach the police line at the Pont de la Concorde, but the line held. There were lesser riots elsewhere in Paris that evening. All told, fourteen civilians and one gendarme had been killed, more than fourteen hundred wounded. The toll increased during Communist rioting the next day, and for days thereafter.

L’Action Française and les Jeunesses Patriotes mourned their dead. The consecrated ground in which Colonel Hubert Henry had lain buried since the Dreyfus Affair became the graveyard of new martyrs. But the temper of the times and of the movements made it difficult to distinguish lamentation from vituperation, especially when, on February 7, the minister of the interior issued orders for the preventive arrest of Maurras and Daudet. “The accursed Chamber of 1932, the Chamber of the Cartel, … is doomed, and it were best that it remove itself of its own accord,” wrote Daudet in response. “Moreover, parliamentary government, which was moribund even before this drama, cannot recover from the carnage that could easily have been avoided by administering justice instead of sheltering Stavisky’s accomplices.… The indictment of Maurras and the seizure of L’Action Française in newspaper kiosks are the twitches of imbeciles at their wits’ end.” Maurras assured the aggrieved families of the dead that “all men and women worthy of the name French” shared the conviction that “the murderous pistols and rifles of democracy” were aimed at a valorous avant-garde. The assassins’ bullets were propelled by envy and by the hatred of idle, gluttonous profiteers for workers, savants, artists, “people who actually produce something.”

The Paris street riots of February 1934.

Unworthy of the name French were Jews. It went without saying (but was said anyway, repeatedly, in the pages of L’Action Française, whose circulation soared) that one Jew had devised the scheme corrupting government and that another Jew, Léon Blum, had contrived to draw attention away from it by drowning protesters in blood.14 Had the Stavisky Affair not been born of the Dreyfus Affair? Had one plot not descended from the other? Daudet declared as much in lectures on “the Jewish question.” Like the earlier scandal, the recent one threatened the strength and integrity of France, in which one hundred thousand Germans, many of them Jews, had found refuge from the Third Reich. “I want to draw the attention of our innumerable readers … to another aspect of the conspiracy, which ended in a bloodbath,” he wrote. “The fact that Daladier appointed Joseph Paul-Boncour [formerly minister of foreign affairs and allegedly Arlette Simon Stavisky’s lover] minister of war has great symbolic weight.15 For it is certain that Lieutenant Colonel Barthe, who organized the butchery, could not have done so without the authorization of his superior, Paul-Boncour. Léon Blum himself admitted that he told Daladier to ‘resist’—in other words, to accelerate the massacre—on Wednesday morning, the 7th. But for several weeks, Blum, the real head of the Cartel, had been hectoring Paul-Boncour to disarm, in spite of Germany arming herself to the teeth with the obvious goal of seeking revenge.” What amounted to treason, in Daudet’s view, was opposed only by extraparliamentary patriotic organizations such as the Croix de Feu, his own Camelots du Roi, students, and the Jeunesses Patriotes. He noted that the protection Stavisky purchased in Parliament coincided with the “shady designs” of Blum and Paul-Boncour, hampering France’s ability to defend herself against Germany.

After February 6, 1934, France provided L’Action Française and kindred movements a resonant sounding board for the drumroll of xenophobia. In March, Bernard Lecache, the founder of the Ligue Internationale Contre l’Antisémitisme (LICA), observed that hatred of Jews was flagrant. A report approved by Paris’s chamber of commerce on the situation of foreigners in France welcomed immigrants “who bring us their money” but urged that those bred in “ghettos” and “unworthy of living under the sky of France” be deported forthwith. Chamber of commerce reports about the “foreign menace” led to the passage of laws requiring artisans to obtain an identity card and street peddlers to reside in France for five years before plying their trade. In 1935, French physicians would prevail upon the government to pass a law making the practice of medicine by foreigners—especially Jews fleeing Nazi Germany (where, in April 1933, Jewish physicians had been denied government insurance reimbursement for their services)—all but impossible. Even so, the journal of the French medical society would, three years later, denounce “the scandal of excessive naturalizations.”

On February 7, 1934, amid violent counterdemonstrations in which eight more people died, Daladier and then his cabinet members, submitted their resignations after only one week in office. L’Action Française commented that his regime would preserve from its short and sinister career only the shame of having, for the first time since the war, caused French hands to shed blood. That day, Albert Lebrun, president of the Republic, asked a septuagenarian deputy known for his conservatism and amiability, Gaston Doumergue, to form a “government of national salvation.” It was much to ask of him. Doumergue had been in office for less than a week when left-wing parties called for a general strike and a protest rally. The police expected another riot, but on February 12 demonstrators in the hundreds of thousands gathered at the Place de la Nation—Socialists and Communists coming from opposite directions—to hear Léon Blum and Jacques Duclos address them from separate tribunes. “Feburary 12 will henceforth be a historic date,” Blum declared. “With dignity and calm you have exhibited to fellow Parisians the strength of democracy. We will reserve that strength for the defense of the Republic.”

A demonstration of the Vigilance Committee of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, organized in March 1934 in response to the right-wing riots of February. Marching in the front row is André Malraux, who had recently published La Condition Humaine.

Doumergue appointed a commission to investigate the Stavisky Affair and got down to business as best he could with a liberal majority in the Chamber and a cabinet that included Pierre Laval and Marshal Philippe Pétain, who was already being hailed in a widely distributed pamphlet entitled C’est Pétain Qu’il Nous Faut! as the man chosen by Providence to lead an autocratic state. One solution to the task of reconciling the irreconcilable was to unyoke the executive from the team of factional horses pulling the legislature apart and issue executive decrees, which Doumergue regularly did during his nine-month tenure, shaping an agenda rather like Tardieu’s.

For the militant leagues, business as usual was a sobering outcome.16 The blood they had shed brought them nothing of the new order they envisioned, only regrets that they had not coordinated their maneuvers and the hope that a truly tactical effort the next time might rouse public opinion to better effect against the “parliamentary and individualist Republic that divides and corrupts.” As a result, the Jeunesses Patriotes and Solidarité Française, with the blessings of L’Action Française, announced the formation of a “national front” on May 7, 1935.17 They stated that its mission was to marshal all the forces of the nation against the “anti-French red front” and to make common cause should any one of its constituents be threatened or come under attack. “The royalist and Fascist shock troops have experienced their strength, and their audacity will grow,” warned Léon Blum, little suspecting that a year later, shortly before he became premier, their audacity would lead right-wing louts to drag him from his car and beat him bloody.

In January 1934, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle spent a week in Berlin, under the auspices of a Nazi youth group eager to promote Franco-German friendship. With uniformed members of the Sturmabteilung and the Schutzstaffel guiding him around the city, he looked like a Parisian swan attended by brown cygnets. The tour proved to be immensely seductive. Reawakened in him was nostalgia for the camaraderie of the trenches, according to Bertrand de Jouvenel, his friend and traveling companion.18 He put Jouvenel in mind of Alfred de Vigny’s post-Napoleonic officers marking time in desultory love affairs while longing for mortal combat. He knew what Robert Graves meant by “Death was young again,” in the poem “Recalling War”:

Natural infirmities were out of mode,

For Death was young again: patron alone

Of healthy dying, premature fate-spasm.

Fear made fine bed-fellows. Sick with delight

At life’s discovered transitoriness,

Our youth became all-flesh and waived the mind.

Jouvenel had the impression that war and Fascism were all that brought light to Drieu’s pale blue eyes. The previous year Drieu had written a play called Le Chef, one of whose protagonists declares, “When one kills freedom, it did not have much life left in it. There are seasons—a season for freedom, a season for authority.”

Drieu would not have sought in Berlin an answer to his longings for release from the curse of self-doubt and the anguish of solitude if he had not already found it or concluded that the key was totalitarian authority. On February 6, at the Place de la Concorde, he witnessed what he took to be a spontaneous explosion of French instinct, ardor, and pride. It was la furia francese at its most impressively brutish, and brutishness had always entranced him. In a memoir he wrote, “The rugby scrums and boxing matches I saw during my student days at Shrewsbury utterly disconcerted me, but didn’t change my fixed habit of only dreaming about sports. I dreamed of the roughest ones, of rugby scrums and boxing matches.… I continued to shy away from the thing I knew to be essential, which was that I become a brute capable of holding my own against brutes.”19 Until February 6 he had been a mere observer, he wrote. His was the “fallen state that gives birth to novelists.” Now he decided to join the scrum but, as with everything in life, still debated with himself which colors to wear. Should he follow the examples of Malraux, Gide, and Aragon and turn left instead of right and look to Moscow for salvation rather than Berlin? Did one direction hold greater promise than the other of making him “a new man”?

The spectacle staged by the Nazis at their party congress in Nuremberg in 1935 (and projected beyond Germany in Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will) seemed to be a decisive event for Drieu. He attended the congress and came away exuberant. “I have never felt such artistic emotion since the Ballets Russes. This nation is intoxicated by music and dance.” It was with the same exuberance that he had marched to war in 1914 carrying Nietzsche in his knapsack. “I should only believe in a god who would know how to dance,” says Zarathustra. “And when I saw my devil I found him serious, thorough, profound, and solemn: he was the spirit of gravity—through him all things fall.”20

The emotional logic that enabled Drieu to reconcile ballet and brutishness was at play in October of that same year, when he and sixty-four compatriots issued the “Manifesto of French Intellectuals for the Defense of the West,” justifying Italy’s war against “an amalgam of uncivilized tribes” in Ethiopia. Signatories of the manifesto, who eventually numbered a thousand or more, protested that the League of Nations had condemned the invasion and imposed sanctions on Italy in accordance with a fallacious creed of “legal universalism” making no distinction between the superior and the inferior, between the civilized and the barbaric. The slaughter of four hundred thousand Ethiopians had been accomplished in a “civilizing spirit,” they insisted. Colonial conquest bespoke Europe’s “vitality.”

1Laval is chiefly remembered as Pétain’s premier during the Vichy regime; he was tried and executed after the war for “intelligence with the enemy.”

2In a comprehensive view of postwar France, two French historians, Jean-Pierre Azéma and Michel Winock, observe that the public ethos was generally hostile to change. “New” was as feared in France as it was glorified in the Soviet Union, and the myth of the “belle époque,” cultivated after 1918, bore witness to this nostalgia for a lost golden age. “The springs of the republican regime, already worn before 1914, lost even more resilience during the war. When the time came to modernize, the spirit of innovation was lacking. After years of hemming and hawing, the gold-backed franc was restored, albeit at one-fifth of its previous value. But more difficult to restore was the republican spirit, which had suffered comparable depreciation. In retrospect, the twenties appear to have been a quagmire.”

3Édouard Herriot, leader of the Radical Party, twice premier, and perennial président de la Chambre (Speaker of the House), was a graduate of the École Normale Supérieure. He taught advanced classes in literature and rhetoric at lycées in Nancy and Lyon and was awarded a prize by the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques for a work on Philo and the Alexandrian school. Among his thirty books are a life of Beethoven and a history of French literature. He entered politics during the Dreyfus Affair, as a Dreyfusard.

4Pius X died in 1914. He was succeeded by Benedict XV and Benedict by Pius XI in 1922.

5Chiappe also forbade Felix Weingartner’s appearances as conductor of the Pasdeloup Orchestra. It is worth noting that Dreyfus himself was still alive to observe the longevity of the myth that bore his name. He died in 1935.

6The Jewish News Archive of March 7 reported that Jewish circles were much concerned by the demonstration of anti-Semitic strength in France. “The anti-Semitic passions which ran high during the Dreyfus Affair have been found by this new affair to be still alive in France, the royalist and military circles who contended that the Jew Dreyfus was guilty of appearing to have a strong following still, despite the verdict of history, even to the extent of a woman publicly proclaiming herself Esterhazy’s daughter and making an attack in the theater on M. Richepin [the French adapter of the play] because it depicted Esterhazy as the traitor.”

7In 1928 Coty bid for working-class support with a newspaper named after Marat’s paper of the revolutionary period, L’Ami du Peuple. Among other articles of commentary published in it was one entitled “France d’Abord! Avec Hitler Contre le Bolshévisme!”

8Janet Flanner published several long articles about Marthe Hanau in the New Yorker in the 1930s.

9Stavisky’s father had committed suicide several years earlier, after trying to save him from another financial embarrassment.

10Lloyd’s of France had invested 5 percent of its total assets in the crédit municipal.

11Marinus van der Lubbe, the alleged arsonist, was active in the unemployed workers’ movement in Holland. He moved to Germany in 1933 and joined the Communist underground. The Sturmabteilung, the SA, had been committing particularly brutal murders in a reign of terror since the summer of 1932. The most widely publicized took place in the Silesian town of Potempa on August 10, when SA thugs trampled to death a Communist miner in the presence of his mother and brother.

12A number of men in high public office, representing the moderate Left, belonged to the French Masonic Lodge called the Grand Orient de France. To Solidarité and other elements of the Far Right, Masonry signified devotion to the ideals of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment.

13Badgered by young Communists en route, they paraded under a banner that read, “We want France to live in order and propriety.”

14Not wanting to bear the same given name as Léon Blum, Léon Daudet took to calling him Béla Blum, with Béla Kun in mind. Kun, born Kohn, led the Hungarian Revolution of 1919 and presided over the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

15Daladier had appointed Paul-Boncour minister of war only two days before the riots of February 6.

16It was not altogether business as usual. During the parliamentary session preceding the confidence vote for Doumergue, one deputy, Xavier Vallat—a one-eyed, one-legged veteran who later became the Vichy government’s first commissioner of Jewish affairs—proclaimed that he was happy to be hearing the voice of France after having heard “those of Israel and of Moscow.”

17Thirty-seven years later, Jean-Marie Le Pen founded the Front National in its second incarnation.

18Bertrand de Jouvenel was ten years Drieu’s junior. The son of an old-line aristocrat and a Jewish heiress, he had written several books on economics, most recently La Crise du Capitalisme Américain. His love life, which seems to have rivaled Drieu’s, included an affair with his stepmother, the novelist Colette (whom he called Phaedra) and, at the time of his voyage to Berlin, with the American journalist Martha Gellhorn, a staunch anti-Fascist, who became an eminent war correspondent and, in 1940, Ernest Hemingway’s third wife.

19“In the street I was at the mercy of anyone who crossed my path,” he continued in this memoir. “During skirmishes in the student quarter, I took advantage of the mayhem and of the chance to dodge blows that would have destroyed me.… I became furtive, elusive, ironical. Erotism served as a compensation, a substitute.”

20After Nuremberg, Drieu visited Berlin, where he struck up a friendship with the novelist Ernst von Salomon, who had been a member of the postwar paramilitary organization Das Freikorps, had been imprisoned for his role in the assassination of Walther Rathenau, Jewish foreign minister of the Weimar Republic, and had written sympathetically about the social estrangement of many German solidiers after 1918, as in this passage: “They constituted seats of discontent in their companies. The war still inhabited them. It had formed them; it had awakened their most secret penchants; it had given meaning to their lives … They were rough beings, untamed men cast out of the world, alien to bourgeois norms, scattered about, who assembled in small bands to make some sense of their combat experience.”