Camille Chautemps, the Radical ex-premier, succeeded Léon Blum on June 22, 1937, and held office for eight months, presiding over a cabinet in which Radicals susceptible to overtures from the Right outnumbered Socialists sworn to the social and economic agenda of the Popular Front. It would appear that Chautemps regarded himself as an understudy appointed to go through the motions of government until Édouard Daladier came onstage. He governed during that critical period by cunctation: little was done when decisiveness was most needed. The image of a progressive nation projected at the World’s Fair belied France’s economic futility. The franc tumbled but not enough to make French exports competitive. Factories closed. The budget deficit reached 28 billion francs. Labor strikes reduced government revenue, and military expenditures, inadequate though they were in light of German rearmament, tithed every other program. With France’s currency bound to the gold standard and her gold reserves dwindling, the finance minister, Georges Bonnet, an advocate of austerity, arms reduction, and appeasement, could not expand the money supply as Roosevelt had done in the United States, even if he had been disposed to recommend it.1

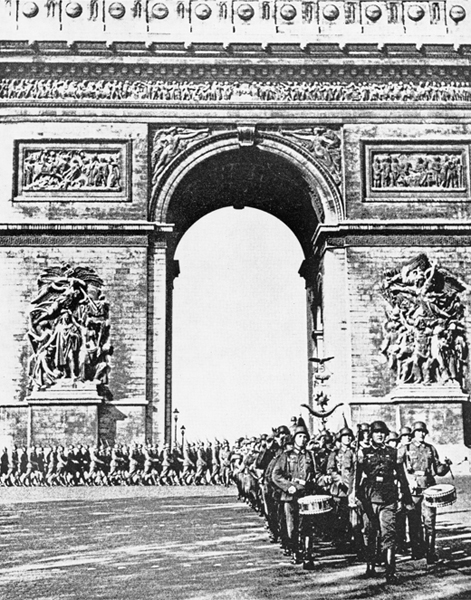

Strikes, which required government arbitration, were the bane of a waffling premier’s existence. Reluctant, on the one hand, to rule in favor of management lest labor prevail upon Socialists and Communists to end their marriage of convenience with his own Radical Party and fearful, on the other, of ruling in favor of labor lest he alienate the entrepreneurial class, he ruled this way and that. Conciliation was seen as the strategy of an invertebrate born to slither under fences, alternating between Bonnet’s orthodox prescriptions on one side and reform on the other. In January 1938, Chautemps, exasperated by strikes, resigned from office after clashing with Communists. One week later he formed a new cabinet, almost entirely Radical (which is to say, centrist) in composition, assuring his left-wing colleagues that he remained loyal to the Popular Front. “No man can possibly pretend to direct other men solely on the basis of the law of property applicable to things,” he declared. “A captain of industry must have his authority respected; but he must endeavor every day to merit the position of director conferred upon him by chance.” (Conservative deputies loudly objected to the words “by chance,” according to Le Populaire.) Chautemps continued: “I am not appealing to a new majority. What I would like, much more than tactical votes, is heartfelt allegiance. Those are the words Léon Blum used, and the phrase was a step toward national reconciliation.… It is said that this ministry can only be a ministry of transition. Well, if I were one day overtaken by events and trampled in the victory of companions to whom I showed the way, I would be very proud indeed.”2 France wanted “normal and peaceful relations” with all states and hoped to find common ground “by an effort of mutual comprehension.” Chautemps was trampled in the victory parade not of companions but of German soldiers marching down the Champs-Élysées.

Looking back, he might have wondered whether bombs exploding in Paris during the World’s Fair only weeks after he became premier had been the clearest portent of all that overtook him. On a Saturday evening in September 1937, two office buildings situated near the Place de l’Étoile had been wrecked by devices powerful enough to hurl masonry across the street. Since both buildings housed manufacturers’ associations, Le Temps lost no time blaming “foreign revolutionaries” adept at “a form of terrorism that is not native to us.” The paper felt certain that those revolutionaries came from “milieux in which the ‘capitalist’ is seen as a public enemy against whom every ‘proletarian’ worthy of the name must consider himself permanently at war.” L’Humanité agreed that foreigners were no doubt responsible for the destruction, but it blamed Fascist agents, citing as a precedent the Reichstag fire of 1933, which the Nazis, who may have been the arsonists, pinned on Bolsheviks to excite public indignation and justify mass arrests. L’Humanité’s editor, Paul Vaillant-Couturier, ridiculed Le Temps. How could a terrorist act benefit the Communist Party in September 1937, when the Popular Front was cohesive and triumphant? he asked. It was a false-flag operation. “There are people inside and outside France who have a vested interest in creating a state of havoc unfavorable to production, dangerous for freedom, fatal to tourism, subversive of peace. The recent history of Spain, to mention only that, offers sufficient evidence of Hitlerian interference in the affairs of neighboring countries.… The guilty parties will be found along the Rome-Paris-Berlin axis.”

On September 17 newspapers reported the footprints of a secret society—not foreign but French, and not Communist but right of right-wing—called La Cagoule, or “the Hood.” At that point its existence was better known to L’Action Française than to the Bureau of Criminal Investigation, for it had been founded in 1935 or 1936 by men, mostly renegade Camelots, bent on making France ungovernable with strategically compelling acts of terror. Soon the name became common knowledge. Le Populaire identified Cagoulards in custody and two traffickers through whom the terrorists purchased German and Italian arms. But a much fuller exposure of their activities awaited the progress of a police investigation. Months passed. Then, in November 1937, a “Fascist plot” began to make daily headlines in the left-wing press, which furnished details of an elaborately organized mafia, its code of honor, its initiation rite, its murders, its impressive arsenals, its staff. On November 23, the Ministry of the Interior condemned the Cagoule as a subversive brotherhood whose structure was, according to documents found in a police raid, patterned after the army’s. It included a high command, internal and external military intelligence agencies, safe houses, and a medical service with nurses and doctors on call. A communiqué from the minister of the interior, Marx Dormoy, noted that the grouping of its members into divisions, brigades, regiments, battalions, and so on pointed to their intention of waging civil war.

Seized documents establish the fact that the guilty had assigned themselves the goal of replacing the freely chosen Republic with a dictatorial regime before proceeding to the restoration of a monarchy.… Discovered in the course of house searches were equipment for counterfeiting identity papers, instructions for the conveyance of arms, precise details about the military guard at political venues in departments neighboring Paris, the weaponry of regiments, detailed maps of Paris’s sewer system with itineraries leading to the Parliament building, the floor plans of left-wing newspapers and of flats belonging to deputies, a facsimile of the signatures of certain ministers, a list of ministers and legislators to be arrested as soon as the signal was given.

The police apprehended the society’s administrative officer, Eugène Deloncle, a naval engineer by training and the wealthy director of large corporate firms. Only later did it come to light that financial support for the Cagoule had been provided by Eugène Schueller, the founder and owner of L’Oréal cosmetics, who offered employment in his Spanish subsidiary to fugitives from French justice.

Right-wing papers made light of incontrovertible evidence and dismissed the false-flag argument as an “odious burlesque” staged by Dormoy to distract attention from Communist intrigue. L’Écho de Paris claimed that Dormoy, who had indulged the Popular Front’s many transgressions since succeeding Salengro, saw arsenals and plots in a few rifles exhumed from the cellars of peaceable Frenchmen who feared, as well they might, the prospect of red revolution.

The Cagoule was disbanded before it mobilized, but not before it reinforced the army of hobgoblins undermining confidence in a Republic seemingly unable to govern. “A dirty stream of undifferentiated hate distorted human and social realities,” writes one historian. “Myths of pervading evil turned superficial disagreements into haunting fears and political differences into vendettas, and the French body politic became incapable of any kind of unity because all foundation for mutual trust had been shattered during these ruthless and bitter fights, which no one carried on with more asperity than the Right. Serious or childish, the plots of the Cagoule helped to convince both sides that all such plots were real.” People old enough to remember were put in mind of the paranoia and messianism of the Dreyfus years. Where evil was pervasive, so was talk of salvation. And where salvation entered political discourse, heroes, saints, and despots were summoned to shame parliamentarians flailing about in a republican morass. Le Figaro declared that France needed a “committee of public safety” to restore order. On May 9, 1938, it devoted much of its issue to Saint Joan, whom it glorified as the brightest of the stellar figures illuminating France’s past. “Can one find in Napoleon’s tomb that which is found in the cradle at Domrémy and on the hard, enchanted road that leads to the stake at Rouen? The festival of July 14, though purified by the blood of martyred soldiers, has repugnant origins. The Maid’s festival is incomparably splendid. Fidelity, political wisdom, military heroism, and holiness are the immaculate spray of virtues offered to us by the fifteenth century; it perfumes all the ages, and arms the generations in their defense of the country.”

Charles Maurras may have been too tired to march with his colleagues in the traditional procession. He had spent a week in Spain as a guest of the insurgent regime, being fêted at Saragossa and at Franco’s headquarters in Burgos, and raising a glass to men who exemplified what he called “the natural advantages of organization, intelligence, science, all the moral and mental levers of civilization over the numerically superior forces of Disorder.”

In 1889, royalists, Bonapartists, and ultranationalist revanchists had placed their hopes for overturning the Third Republic in General Georges Boulanger, dubbed “the providential man.” Half a century later, that title was dusted off by exasperated anti-parliamentarians and conferred upon Philippe Pétain, the marshal glorified for his command at the Battle of Verdun.3 Age had not dulled his luster. Pétain turned eighty-three in 1939, the year Premier Édouard Daladier appointed him ambassador to Spain, where Franco’s army entered Madrid on March 28, ending a civil war that had cost the country half-a-million lives.

The last remnants of the Popular Front disappeared with the confirmation of Daladier as premier in April 1938. Remembered today as a signatory of the infamous Munich pact of September 1938, endorsing Hitler’s annexation of a Czech province, the Sudetenland, Daladier, unlike Chamberlain, did not believe that one more slab of Europe thrown to the beast would definitively sate its appetite for Lebensraum. He believed quite the opposite: that war lay ahead but that France needed time to modernize her air force and study the proper deployment of her tanks. What he believed mattered less, however, than what he did and didn’t do. Chamberlain’s cravenness, the daunting prospect of going it alone against Germany (with whose military might he was well acquainted), his own divided party, and a poll that showed 78 percent of the French electorate favoring appeasement all combined to make Daladier Chamberlain’s fellow fool without persuading him in his tortured self-abasement that the betrayal of a democratic ally had purchased “peace in our time.” A nation still mourning the dead of 1914–18 cheered him when he returned from Munich, only to find itself placed belatedly on a war footing.4 (Daladier’s response to the cheering was an aside to his aide Alexis Léger: “Ah, the imbeciles [les cons]! If they only knew what they are acclaiming.” Winston Churchill voiced the same sentiment rather more eloquently in the House of Commons: “England has been offered a choice between war and shame. She has chosen shame, and will get war.”)

Intense rearmament required greater productivity, and Daladier overrode the law that crowned Popular Front legislation—the forty-hour work week. On August 21, 1938, he asserted in a radio broadcast that France alone among industrialized countries allowed its plants to idle two days a week. “As long as the international situation remains so delicate, one must be able to work more than forty hours, and up to forty-eight in enterprises that affect National Defense. Every enterprise needing a longer work week for its operation should be spared useless formalities and interminable discussions.” Conservatives were pleased not only by the measure but by the final dismantling of the Popular Front. A general strike in November fizzled after a day. Having stood it down—for that purpose he had nerve—Daladier carried on as head of government without support from Communists and Socialists.

Something of the internecine hatred that had shed rivulets of blood in 1871, after the Franco-Prussian War—when Germans still camping around the capital witnessed French government troops crushing the Paris Commune—made itself felt in March 1939, when Hitler occupied all of Czechoslovakia. The gathering threat of war did not inspire a sacred union. Anti-Fascists and anti-Communists lambasted each other for France’s inadequate production of arms, its antiquated plants, its reliance on the United States for airplanes. It was all Édouard Herriot’s fault, Maurras claimed in L’Action Française. The onus of having withdrawn French troops from the Ruhr in 1925 fell on him and on Briand. “We shall continue to earn the ill humor of politicians who placed all their hope in the waters of Oblivion.… They dismiss our righteous evocation of their infamies as the apple of discord.”

France owed her present predicament as well, Maurras maintained, to messianic Jews heralding the dawn of a new age with the victory of the Popular Front in 1936. Zion cast an even longer shadow than Hitler. Blum and his coreligionists were the swine who had surrendered France to her mortal enemy. “There is no time to lose; national authority and political policy must be removed from the Sarrauts, the Mandels, the Paul Reynauds, the Dreyfuses, the Rothschilds. This Jewish power needs no more time than it takes to sign an order and the fatal choice will have been made, the iron die will have been cast. The ardor with which the slyest and most suspect of Israel’s servants endeavor to bring about a crisis, though it cost France her peace, is the measure of what they expect to gain from it. Beware of the Rothschilds, of the Louis Louis-Dreyfuses and the madmen who serve them.”5 Provincial newspapers offered more temperate versions of the same indictment. A Radical daily, L’Écho de la Nièvre, brought to book “the men who allowed disorder to reign after the election of May 1936, slowing the industrial production necessary for our national security, above all Léon Blum and Marx Dormoy.” That Zion cast a longer shadow than Hitler was borne out in December 1938, after Kristallnacht, when the German and French governments signed a declaration of mutual amity. Hitler’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was fêted by the French foreign office at a grand banquet on the Quai d’Orsay that the two Jewish members of Daladier’s coalition cabinet, Georges Mandel and Jean Zay, might have chosen not to attend even if they had been invited. Mandel, like his fellow conservative (and Anglophile) Paul Reynaud, had vehemently opposed the Munich pact.

L’Humanité rebelled against press censorship, accusing Daladier, when the legislature granted him emergency powers, of exploiting Czechoslovakia to muffle his critics:

How many times in the past 150 years has a French journalist sat in front of a blank page full of vindictive indignation over measures that violate freedom of the press? These arbitrary acts have seldom brought luck to their authors. Charles X, Louis-Philippe, Napoleon III, and recently Doumergue had tales of woe. Now Daladier is trying to bring off a Napoleonic 18 Brumaire without seeing how desperately things will end. But Bonaparte waged the Italian campaign. All you did, Monsieur Daladier, was travel to Munich.6

Le Populaire proclaimed in bold headlines that the premier’s intention was, under cover of trouble abroad, to intensify his war against the proletariat at home. “Republicans,” it declared, “cannot abdicate in favor of a government whose parliamentary support consists for the most part of minority groups that tend more and more to penalize the working masses.” Did Léon Blum see in Daladier, his former minister of defense, an avatar of the “providential man” destined to subvert the Republic? “You are asking for powers which I understand to be more or less unlimited in nature and in time,” he argued during a parliamentary debate. “I consider this desperate resolution unwise. You wish to present us with a fait accompli, having consulted [no one]. Do you think it advisable to sow division at a time of grave events? to cast suspicion on Parliament and Republican institutions? and to do so not when you are riding a tide of success but in the wake of a diplomatic fiasco [Munich]?” Blum’s foes could have answered his remarks by quoting the column he had written five months earlier, after the Munich pact was signed: “There is not a woman or man in France who will refuse MM. Chamberlain and Daladier their just tribute of gratitude. War is spared us. The calamity recedes. Life can become natural again. One can resume one’s work and sleep again. One can enjoy the beauty of an autumn sun.”

On the day of the debate, March 15, 1939, there was commotion of a different sort several blocks away from the Palais Bourbon at the Gare d’Orléans, where Marshal Philippe Pétain departed Paris to assume his duties as France’s ambassador in Burgos.7 A large crowd packed the vaulted hall of the train station and spilled out onto the Quai d’Orsay. Present were admirals and generals, including Maxime Weygand, retired chief of staff of the French army. An honor guard of gueules cassées—crippled and maimed veterans of World War I—formed up at the head of the staircase leading down to Pétain’s private carriage. A reverent reporter wrote in Le Figaro that the “hero of Verdun” presented “the physical image of perfect aplomb, of that imperturbable calm with which his name is synonymous.” Men doffed their hats when the engine fired up, and Pétain, at the entrance to his carriage, bade them farewell “with a courtesy and charm that seemed the garland of history.” Charles de Gaulle saw in all this the pitiable spectacle of an old man’s vanity.

The scene, though less frenetic, was reminiscent of Georges Boulanger’s departure for Clermont-Ferrand in the 1880s, when crowds gathered at the Gare de Lyon shouting, “He will return!” And the parallel runs deeper, for both departures had political implications. As Boulanger’s reassignment to a provincial garrison was tantamount to internal exile, prompted by the justified fear of anti-republican conspirators organizing a coup d’état, so Daladier may have sought to marginalize a threat to the Republic by relocating Pétain beyond the Pyrenees.

This was by no means Daladier’s only motive. Germany, which had lent Franco a mighty hand in overturning the Spanish Republic, continued to court favor with him and rewarded Spanish newspapers for portraying Hitler in the most advantageous light. Pétain’s principal task as ambassador was to keep Spain neutral in the event of war between France and Germany. The marshal who had received the Medalla Militar from King Alfonso XIII fourteen years earlier for subduing the Moroccan Rif tribes in concert with the Spanish army, stood a much better chance of finding favor with the “Caudillo” than a polished veteran of the diplomatic corps. Franco gave him a chilly welcome, but in due course Pétain accomplished his mission, with the help of gold bullion deposited by the Spanish Republic in the Banque de France, confiscated by the French Republic, and made available to the Fascists.

Pétain had no sooner established himself as ambassador than politicians, the best-known of whom was the former premier Pierre Laval, began courting him, much as Bonapartists and royalists had wooed Boulanger into political life. First it was proposed that he stand for election to the presidency in April 1939. The very notion “horrified” him, he wrote to his wife. He would entertain no more overtures. “I can work two weeks, I can’t work fifteen. I’m deaf and that troubles me.” No matter. He lent his suitors an ear, irritated by their self-interested importunities but pleased to be the object of their courtship.

On September 1, a week after signing a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, the Nazis invaded Poland. On September 3, France and England declared war against Germany. The calls for Pétain’s return became so insistent that Daladier, as much to thwart suspected conspiracies as to create a government of “national union,” offered him the War Ministry. Was he not, according to one of Daladier’s confidants, “an old fetish,” “the great moral figure of the last war, a humane, respected leader whose advice could be precious should disagreements arise between the government and the general staff”? Nothing came of discussions in Paris, during which Pétain, at Laval’s urging, insisted on an immediate entente with Italy. He did not tell Daladier that he was loath to serve in a cabinet of inept civilians. What he did say was that much remained to be done in Spain. “Certain official milieux are still too obliging to German propaganda,” he wrote. “They do not wish to understand that the war in which we are engaged with Hitler’s Germany combined with Soviet Russia is but the sequel to that waged by Spain against Communism for the defense of Christian civilization.” It was Franco’s line, repeated verbatim.

The longer France and Germany temporized on the eastern front, camping opposite each other in what came to be known as the drôle de guerre or “phony war,” the more Pétain longed to make himself heard in councils of war. His wish was granted in May 1940. By then Paul Reynaud, a conservative finance minister, had replaced Daladier as premier and the phony war had turned all too real, with panzer divisions racing across the Ardennes under scores of German Stukas bombing French defenses, and the French army in full retreat. Panic-stricken officials at the Foreign Ministry made a pyre of diplomatic papers. “It was as if the ineffective past of the Third Republic were being consumed in a vast crematorium,” wrote General Edward Spears, Churchill’s personal representative to the French government. On September 18, Reynaud appointed Pétain minister without portfolio and vice premier. He announced his decision in a radio broadcast:

The victor of Verdun, thanks to whom the assailants of 1916 didn’t breach the line, thanks to whom the morale of the French army in 1917 was lifted to victory, Marshal Pétain, returned from Madrid this morning where he rendered many services for France.… Henceforth he will be at my side, placing all his strength and wisdom at the service of his country.

With few exceptions, the French press joined in a collective panegyric of the hero who eternally performs his epic feat, turning the tide of battle. Pétain, the “vanquisher of Verdun,” had in him the stuff of Coriolanus repulsing the Volsces, of Roland at Roncevaux, of Corneille’s Cid putting the Moors to flight, of Joan raising the siege of Orléans. Le Figaro declared that France felt “an immense impression of security.” The Breton paper L’Ouest-Éclair incanted the refrain “Verdun revealed him to the world” and informed readers that it was Pétain who, on February 26, 1916, uttered the rallying cry “Courage! On les aura!” (Courage! We’ll lick them!), breathing life into battle-worn troops. The article noted, “It is reported that at the funeral of King Alexander of Serbia, Marshal Goering, struck by the prestige of Marshal Pétain, walked a step behind him and couldn’t take his eyes off the sky-blue silhouette.”8 Louder than all flourishes was Maurras’s in L’Action Française: “At last! … Necessity proved as wise as reason. At last, the military hierarchy and the political hierarchy coincide.… Veterans of Verdun have all told us how faith and hope were restored to the most downcast when, on a frightful early winter morning, word spread from trench to trench: ‘Pétain! Pétain! Pétain is taking command!’ This memory spares us from having to insist upon the virtue of prestige. But in 1916 it shone only within our lines. In 1940 it will light up the sky and daunt the enemy.”9

On June 11, as German divisions approached the capital from the north, the French chief of staff, Maxime Weygand, proclaimed Paris an open or undefended city. One week earlier, the English general Edward Spears had implored Pétain in his office on the Boulevard des Invalides to oppose colleagues—Weygand among them—who demanded that the alliance with England be renounced and a separate armistice negotiated. Pétain demonstrated the hopelessness of France’s military situation on a battle map, then proceeded to blame politicians and exonerate the general staff—all except Charles de Gaulle, his protégé, his bête noire, and the author of La France et Son Armée, who, he felt, had not fully acknowledged his own contribution to the book. “Not only is he vain, he is ungrateful,” Pétain said of the stiff-necked brigadier. When Spears mentioned Joan of Arc, Pétain, apparently more interested in martyrdom than in victory, insisted on reading a commemorative speech he had given at Joan’s stake in Rouen. The Englishman found him “infinitely pitiable” and parted with the feeling that France was receding behind a glorious past evoked in the quavering voice of an old man.

No sooner did Weygand proclaim Paris an open city than the government moved south and established temporary quarters in the Loire valley. Churchill and Anthony Eden came over from London, circling beyond the range of German anti-aircraft fire but flying into the teeth of a dispute between résistants, notably Paul Reynaud, and capitulators who declared that an armistice was indispensable to France. On his return, Churchill described Pétain as a dangerous man “who had always been defeatist, even during the last war.”

Churchill conferred with Reynaud for the last time on June 13 in a lightning-quick visit. General Weygand informed the cabinet that German troops were expected to enter Paris the next day, whereupon Pétain read a document originally meant for Churchill’s ears stating that a government in exile would be no government at all. Treating separately with Germany was presented as virtue rather than perfidy, as the courageous stand of Frenchmen rooted in French soil rather than cowardice. Surrender would be painful, but the pain would make amends for the delinquency of a Socialist regime and the corrupting influence of internationalism. France would purge herself. She would recover her selfhood, a prisoner but within her own boundaries. “A French renaissance will be the fruit of suffering.… I declare, for myself, that I shall refuse to leave native soil, even if it means withdrawing from the political scene. I shall remain among the French, to share their pain and their miseries.” Only an armistice could save the life of “eternal France.”

The administration moved farther south, to Bordeaux, along with deputies, senators, civil servants, journalists, and petitioners (as in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, when the Germans besieged Paris). Ministers and officers hoping to salvage something of the general staff’s prestige with an armistice engaged the party of resistance in heated debate. The whole city became a rumor mill. After several days, Reynaud, who had hoped that Roosevelt would come to the rescue, admitted defeat, tendered his resignation, and on June 14 broadcast a final message to the French nation: “All Frenchmen, wherever they are, will have to suffer. May they prove themselves worthy of their country’s great past. May they treat one another fraternally. May they close ranks around the wounded fatherland. The hour of resurrection will come.” His last word as premier, recommending that President Albert Lebrun invite Marshal Pétain to assemble a cabinet, was spoken between clenched teeth. Armistice negotiations began immediately and resulted in a treaty the draconian terms of which avenged those imposed on Germany by the armistice of November 11, 1918.

The victorious German army parading down the Champs-Élysées, June 14, 1940.

News that a line of demarcation would slice across France’s midsection just north of Vichy in the Auvergne, with enemy troops also occupying the entire Atlantic coast, had not yet been published when Premier Pétain consoled and chastised his countrymen in a speech aired on June 25. His intention was to explain how and why the army had come to grief. The price exacted by Germany would tax everyone’s life. But France, he assured them, would not have dishonored herself. Her leaders would remain on French soil, unlike expatriates prating from London and North Africa. Their loyalty to the earth vouched for the truth of their words: “The earth does not lie. It will be your refuge.” Moreover, adversity was not without its blessings. Cognizant of his reputation as “the providential man,” Pétain insinuated that defeat may have been a fortunate fall. He repeated what he had said on the eve of Germany’s victory parade down the Champs-Élysées, that the French had brought defeat upon themselves: “It stemmed from our laxity. The spirit of hedonism leveled all that the spirit of sacrifice had raised. I invite you, above all, to a moral and intellectual housecleaning.”10 As in the 1870s after the Franco-Prussian War, when the Third Republic was struggling to survive its infancy under the rule of conservatives who promulgated a “Moral Order,” so the Republic in its death throes heard its last premier announce “a new order.”

The call for mea culpas and self-cleansing was echoed by La Croix. “Why did God permit this frightful disaster?” asked the abbé Thellier de Poncheville. “Let us fall to our knees. We have many faults to expiate. An official enterprise of dechristianization which struck the vitality of our fatherland at its very source. Too much blasphemy and not enough prayer. Too much immorality and not enough penitence. The forfeit had to be paid one day. The hour has come to repent of our sins in our tears and our blood.” In Le Figaro, François Mauriac, Charles de Gaulle’s future champion, wrote that France had not heard a mere individual speaking on the radio but “the summons of a great humiliated nation rising from the depths of our History.” Pétain spoke for those who had fallen at Verdun. “His voice, broken by sorrow and age, uttered the reproach of heroes whose sacrifice, because of our defeat, had been in vain.” L’Action Française transmitted its sentiments through a satellite in Bordeaux: “Great fortune has crowned us in our immense misery. God had prepared a great leader for us. Marshal Pétain has gathered up France on the very day of its distress.”

General de Gaulle in England calls on his compatriots to continue the fight, after the Pétain government signs an armistice with Hitler. “Nothing is lost, because this war is a world war. In the free universe, immense forces have not entered the fray. One day they will crush the enemy. On that day, France must be present at the victory.”

On June 29, the peripatetic government evacuated Bordeaux, which became a German port. Deferring to its aged premier it reestablished itself in Vichy, a spa town well supplied with hotel rooms and enough mineral water to purge the diminished nation. On July 9, what remained of Parliament convened in Vichy’s casino to consider a proposal that the constitution be changed. Several deputies and senators who would have dissented—Daladier, Pierre Mendès France, Georges Mandel, and Jean Zay, among others—had boarded a ship bound for Morocco three weeks earlier when it was thought that the entire government would embark and continue the fight from North Africa.11 On July 10, the National Assembly, with only eighty senators and deputies objecting, authorized Pétain to promulgate new laws. On the following day the Third Republic died, all powers being assigned to Pétain as “chief of state”; the office of president being abolished; and Parliament adjourned.

German flags hanging from the terrace of the Palais de Chaillot.

In his inaugural address, Pétain sang the praises of discipline and work. “The labor of Frenchmen is the supreme resource of the Fatherland. It must be sacred,” he declared.

International capitalism and international Socialism, which exploited and degraded it, played prominent roles in the prewar period. They were all the more sinister for acting in concert while appearing to cross swords. We shall no longer tolerate their shady alliance. In a new order, where justice will reign, we will not admit them to factories and farms. In our warped society, money—too often the servant of lies—was an instrument of domination.… In France reborn, money will only be the recompense of effort. Your work, your family will enjoy the respect and protection of the nation.12

Marshal Pétain greeting schoolchildren in Vichy, 1940.

Laws calculated to “remake” France were drafted in great haste during the summer of 1940. Six days after Pétain’s speech, the sons of foreign-born fathers learned that they could neither practice law nor serve in government. On July 22, all naturalizations approved since 1927 became subject to review. On July 30, a Supreme Court was established for the express purpose of finding ministers of the Third Republic guilty of failing in their duties or betraying the public trust. On August 13, secret associations, above all the Masonic Order, were banned. By law, anyone who came under suspicion of “endangering the safety of the state” could be arrested and imprisoned. October marked the beginning of Vichy’s anti-Semitic campaign. Decrees excluded Jews from public office and liberal professions; Algerian Jews lost their citizenship; internment camps filled with refugees from Nazi Germany.

The festivities of July 1939 celebrating the 150th anniversary of the French Revolution were still vividly remembered when “Work, family, fatherland” replaced the republican motto “Liberty, equality, fraternity.” This brought immense satisfaction to Charles Maurras, who felt that his editorial jeremiads had, like a desert cactus, unexpectedly flowered after growing needles for forty years. “People have spoken about the ‘divine element’ in the art of war,” he wrote. “Well, the divine element in the art of politics has shown itself in the extraordinary surprises the Marshal has reserved for us.”

And where Maurras led, the royal pretender, the Comte de Paris, followed. “This providential man,” he wrote of Pétain, “has managed to accomplish a triple miracle: he has prevented the total disappearance of the fatherland; he has by his presence alone enabled the country to stay alive; and he has set France on the path of its great traditional destinies by breaking with the principles of the fallen regime.”

The “État Français” became even more the simulacrum of an independent state when, in November 1942, after the Allies landed in North Africa, German troops crossed the line of demarcation to defend against a Mediterranean invasion.

1Bonnet, who had briefly served as France’s monolingual ambassador in Washington, made no secret of his aversion to New Deal economics and his hostility to Roosevelt.

2In May 1940, when the French army was retreating from the Germans helter-skelter, Georges Mandel said of Chautemps, his fellow minister and vice premier, whom he regarded as a prime specimen of the political class’s fecklessness, “He is rehearsing the speech he will deliver as Chief Mourner should France drop dead.”

3In his account of the battle, Pétain praised the performance of the turreted guns and the fixed fortification system when in fact conventional field artillery in the open had inflicted much more damage on the enemy. This misrepresentation influenced France’s calamitous decision to build the Maginot Line.

4On July 12, six weeks before the Munich agreement, Daladier declared in a major speech, portions of which were published in Le Temps, that France’s commitments to Czechoslovakia were “ineluctable and sacred.” Precisely because these commitments existed and France’s intention was to respect them scrupulously, he continued, “she is entitled to exert all her influence over the country to which these guarantees have been given to favor conciliation.… Her bounden duty is to spare no effort to maintain peace.” In England, Chamberlain’s foreign minister, Lord Halifax, voiced his sentiments in a letter to the former prime minister Stanley Baldwin: “Nationalism and racialism is [sic] a powerful force but I can’t feel that it’s unnatural or immoral! I cannot myself doubt that these fellows [the Nazis] are genuine haters of Communism, etc.! And I daresay if we were in their position we would feel the same!” Pierre Flandin, a former premier and holder of various portfolios, put it to an interviewer from Le Petit Parisien that economic pragmatism should be France’s watchword, that the idealistic opposition to dictators and concern with the “Jewish question” worked against the country’s essential interests.

5Another of Léon Daudet’s favorite targets, Louis Louis-Dreyfus belonged to a rich family of global commodity merchants. He owned the newspaper L’Intransigeant and had served for many years as a deputy and senator. The voices raised against Jews for denouncing the Munich pact and thus exposing France to the hell of another war included politicians of the left as well as the right, especially those associated with the bimonthly La Flèche, and in particular Drieu’s former friend Gaston Bergery. In the anti-Communist and anti-Semitic paper Combat, Maurice Blanchot, a regular contributor, who achieved fame after 1945 as a literary theorist, declared, in response to the furor over Hitler’s invasion of the Rhineland in 1936: “There is, outside of Germany, a clan that wants war and, under color of prestige and international morality, insidiously propagates the case for war. It is the clan of former pacifists, revolutionaries, and Jewish émigrés who will do anything to bring down Hitler and put an end to dictatorships.” Condemned in this article were “unbridled Jews” who, in a “theological rage,” clamored for immediate sanctions against Nazi Germany.

6In the revolutionary calendar 18 Brumaire was the date of Napoleon’s coup d’état, overthrowing the Directory and establishing the Consulate. In comparing Daladier to Napoleon, L’Humanité obviously had in mind the opening lines of Karl Marx’s Le 18 Brumaire de Louis Napoléon: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

7As previously noted, the nationalists would not enter Madrid until March 28.

8In 1934 King Alexander of Yugoslavia was assassinated by a Bulgarian nationalist during a state visit to France.

9Maurras, who was all for the invasion of the Rhineland in the 1920s, adamantly opposed France’s declaration of war in 1939. On August 26, 1939, six days before Germany invaded Poland, he wrote, “Jews, or friends of Jews, these gentlemen are in close contact with the powerful Jewish clique in London.… If today our people allow themselves to be slaughtered unsuspectingly and vainly at the behest of forces that are English-speaking Jews, or at the behest of their French slaves, then a French voice must be raised to proclaim the truth.”

10“The capitulation of the government was less dreadful [to those in command] than a military debacle,” Raymond Aron writes in Chroniques de Guerre. “General Weygand, whose political conservatism dominated his military thinking, feared that pockets of revolutionary resistance would form within the throng of routed troops. This obsession clouded his view of things. He had responded to the setbacks in Flanders by organizing a continuous line along the Somme. When this fragile defense collapsed, he was confounded by the new dimension of warfare and lost all capacity for synthesis and action.”

11They were placed under house arrest in Casablanca. Zay (Blum’s education minister) and Georges Mandel (Reynaud’s minister of the interior), both Jews, were eventually assassinated by the Vichy militia. Mendès France, another Jew, was imprisoned but escaped. Daladier was handed over to the Gestapo and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where, for a time, his fellow inmates included Reynaud and Léon Blum.

12Money, lies, abstraction, and Jews were cognates in Vichy’s vocabulary of denigration.