FRIDAY, DAY 5

SEXUALITY AND REPRODUCTION

Mitosis

The secret of how human life works can be traced back to the lowly salamander. In the 1880s, a German biologist named Walther Flemming (1843–1905) began studying the larvae of these amphibians. After staining the organisms with a special dye that made them easier to see under a microscope, Flemming tracked how a threadlike material in the nucleus shortened and split in half during different phases of cell division. He named this process of cell reproduction mitosis, after the Greek word for “thread.”

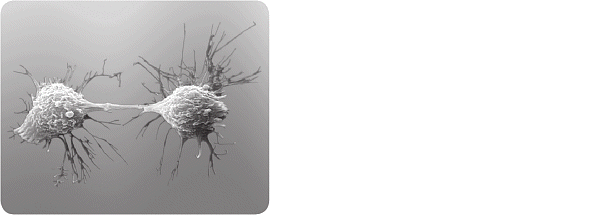

The importance of this discovery, however, wasn’t fully acknowledged until decades later, when scientists identified those threads: They were chromosomes, structures that contain each individual’s genetic information. When a human cell cleaves into two identical structures, it undergoes a series of steps that stretch over 24 hours. The process begins with a division in the cell’s command center, or nucleus: During the step called prophase, the chromatids (a set of two chromosomes joined by a buttonlike centromere) condense into tightly coiled packages. At the same time, two bundles of tubes called centrioles migrate to opposite ends of the nucleus and grow long tubules that stretch toward each other, forming what’s called the mitotic spindle.

In the next stage, metaphase, the chromatids line up neatly along the mitotic spindle. Then, during anaphase, the centromeres release, splitting each chromatid in two; the halves are dragged toward opposite ends of the cell. At that point, telophase commences, and the chromosomes begin to set up a new home: They unfurl, and a nuclear membrane grows around them. Finally, in a process called cytokinesis, the cell pinches in the middle and splits in two, each part having a full complement of chromosomes.

ADDITIONAL FACTS

- Before mitosis occurs, cells undergo a process called interphase, in which their DNA replicates to form a second set in preparation for the onset of mitosis.

- Mitosis can take anywhere from a few minutes to more than an hour, depending on the kind of cells and the type of organism.