The sarcophagus of King Ahiram contains the oldest known example of the Phoenician alphabet, dated to 1000 BCE.

Chapter 4

The Major Players

As we’ve seen, trade in the ancient world was made up of many cultures and civilizations, and each was distinct. The Phoenicians grew into a trading power at a unique time in ancient history, spanning both the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The Phoenicians’ trade partners also experienced unique circumstances, including the Late Bronze Age Collapse. Some of the greatest civilizations of the ancient world (like the Mesopotamians, Greeks, and Egyptians) were still evolving into the prominent cultures we study today while they traded with the Phoenicians.

In this chapter, we will learn more about the civilizations the Phoenicians encountered and traded with. We will also look at some of the leaders in Phoenicia who had a significant impact on trade and at the role of merchants and traders in the ancient world.

Traders in the Ancient World

Social classes were deeply engrained in the ancient world, with religious leaders and royalty at the top of the hierarchy. Because of limited access to education and power, there were not many opportunities for someone from one social class to enter another. Ancient civilizations were also defined by extremes: the immense wealth of the ruling classes was at one end of the social spectrum and the extremely difficult lives of slaves was at the other. But that was less true for merchants or traders, who were the central economic forces of their time. Trade was the cornerstone of the ancient economy. Those employed in trade were capable of making large fortunes. It wasn’t always simple, though. Trade came with immense risk, and all could be lost very quickly with one shipwreck. In some places, such as Greece, the trading class was also made up largely of foreigners, which further complicated their place in the social structure.

Merchants and traders in the ancient Mediterranean were among what we’d today call the middle class. They were still removed from power but had the means to live more comfortably than those of lower social status. In Phoenicia, merchants and traders were second in influence only to kings and priests. Alternatively, in Greece and Egypt, they were wealthy and influential but still outside of very strictly governed bureaucracies. Because power itself was very firmly held by kings and priests, those outside of that sphere could influence culture or win favor with rulers. Yet people with minor influence played only an indirect role in shaping their civilizations’ policies.

Phoenicia

Phoenicia was made up of many independent city-states, meaning that there were many differences between the governance and culture of each individual city. But there were also many similarities that defined them as one culture. These included artistic styles, religion, and language. There were also a few kings who ruled individual city-states in a way that shaped Phoenician culture and trade more broadly.

Hiram I is considered to be one of the most important kings in Phoenician history. Our knowledge of his reign is tightly woven with religious teachings. He ruled Tyre from 980 BCE to 947 BCE, and it was under his rule that the city-state became the most important in Phoenicia. Before Hiram I’s reign began, Tyre was secondary to Sidon, another important city-state. Hiram I established strong trade relations with the kings of Israel, including the legendary King Solomon. Through trade, Hiram I became extremely wealthy. He made Tyre one of the trade centers of Phoenicia, based largely on Tyrian dye.

Another king of Tyre who was historically significant was Pygmalion, who ruled Tyre from 831 BCE to 785 BCE. Pygmalion established numerous colonies, including Kition on Cyprus and Sardinia. He also played a role in the founding of Carthage in 814 BCE, which went on to be one of the most influential capitals of the ancient world. Although the exact circumstances of the founding of Carthage are unknown, legend holds that Dido, the sister of Pygmalian, fled Tyre and founded Carthage in exile. She and the kingdom she built around Carthage feature heavily in Greek and Roman myth, including works by Virgil.

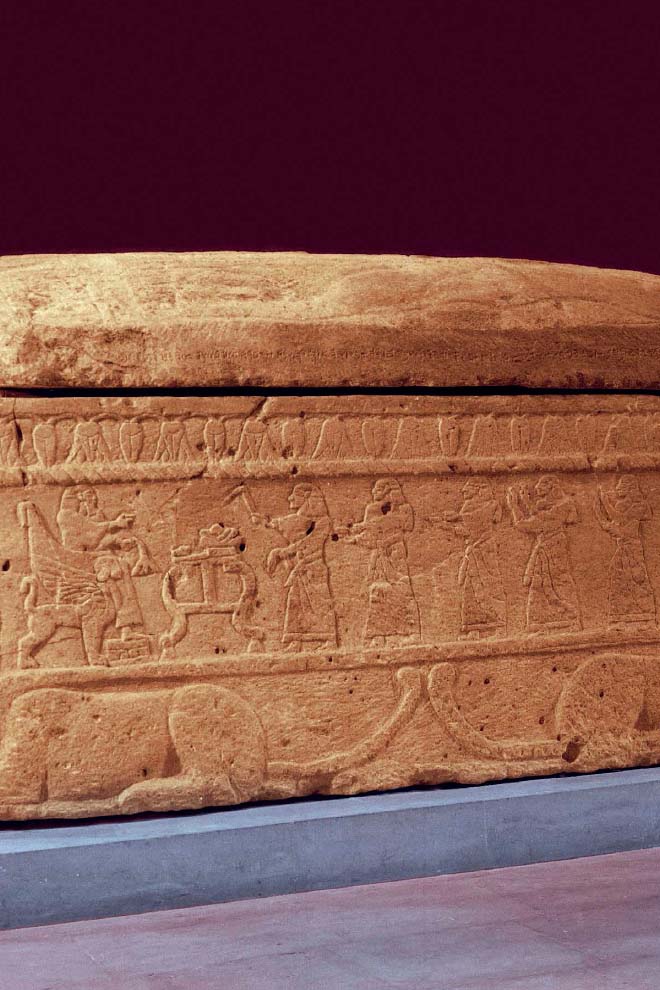

Though we do not know exactly when the Phoenician alphabet was created, it is first seen on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram, who ruled Byblos around 1000 BCE. His tomb was found in 1923 by French archaeologist Pierre Montet. The inscription on the sarcophagus is believed to be a curse against those who would disturb the tomb. This curse is the oldest known example of the Phoenician alphabet.

Greece

Greek culture during the time of the Phoenicians can be broken into two periods. The first was the Mycenaean Age, which took place between 1600 BCE and 1100 BCE. The Mycenaean Age is the closest to what we think of as ancient Greece and saw the rise of Athens, Thebes, and other legendary city-states. Trade flourished under the Mycenaeans, as it had under their predecessors the Minoans. The higher classes were immensely wealthy during this time, giving rise to craftsmanship and art creation. It was under the Mycenaeans that Linear B, the first Greek writing system, was developed. Deities worshipped during the Mycenaean Age remained part of Greek mythology through the Greek Empire’s peak in later centuries.

The second period of Greek history that intersected with Phoenician trade dominance was the Greek Dark Ages, which came after the Late Bronze Age Collapse. Following the Late Bronze Age Collapse, culture in Greece became more localized. Thus, each city-state took on its own traditions and styles. Large-scale projects, such as large buildings or wall painting, were not undertaken during this time. Trade became less frequent. Writing stopped among all but the highest elites, and many villages were abandoned completely. It was during this time that the Greek theory of polis, or independence, was solidified. This development set the stage for the democratic form of governance that we know the civilization for today.

This fresco was created by Greek Minoans on Santorini shortly after the Phoenicians became prominent regional traders.

The Greek Dark Ages lasted until around 800 BCE, by which time archaeological evidence suggests city-states were recovering. This was also around the same time that Phoenician trade reached its height, suggesting a connection between the regional recovery from the Late Bronze Age Collapse and flourishing Mediterranean trade.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia, in the modern Middle East, was one of the greatest and most culturally important civilizations of the ancient world. During the Phoenician period, it was held by numerous dynasties and empires, beginning with the Old Assyrian period from the sixteenth to the eleventh centuries BCE. The Assyrians were defeated by the Kassites of Babylon in 1595 BCE. In the eleventh century BCE, the Hittites ruled the area.

During the period before the Late Bronze Age Collapse, Mesopotamia made significant advances in mathematics and science, as well as in literature and writing. The Babylonian numeral system became the basis for many measurements still in use today, including the twenty-four-hour day and sixty-minute hour. The libraries of Mesopotamia were among the most celebrated and important of the ancient world. A great deal of literature was translated across languages, such as the extinct Sumerian language. Men and women could read, which made their culture unique among ancient civilizations.

Ancient Mesopotamians were among the first to create codes of law, including the legendary Code of Hammurabi, which was written around 1780 BCE. Under these laws and those that followed, historians have found a gradual move toward restriction of women’s rights and a worsening in treatment of slaves. Power was held tightly by hereditary kings who were believed to be gods. In the home, men held all authority. Although Mesopotamian cities were city-states, they all paid taxes to the ruling authority.

The Late Bronze Age Collapse took place in phases across Mesopotamia. In the north, Assyria remained largely intact, with a strong central government and an effective military. Babylon, however, was overrun by invading forces, including Aramaeans and Suteans. These invasions meant that there are few recordings of this time period from city-states across Mesopotamia.

But the collapse’s impact was short lived, perhaps due in part to the continued strength of the Assyrians. In the late tenth century BCE, Assyrian king Adad-nirari II conquered Mesopotamia, starting the Neo-Assyrian Empire. That empire would eventually become the largest mankind had ever seen. It encompassed Egypt in the southwest, Iran in the east, and moved up into modern-day Russia in the north. The Neo-Assyrian Empire stood from 911 BCE to 605 BCE, falling to the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which began growing in around 620 BCE.

Although they were largely independent, during this time many Phoenician city-states were part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Assyrian control was not constant. However, kings like Tiglath-Pileser III and Ashurbanipal took control of cities like Tyre and Sidon. Control of Phoenician trade ports brought in a great deal of revenue for the Assyrian Empire. Surprisingly, it did not impact Phoenician trade or Phoenician culture significantly.

Egypt

The Phoenician trade routes were established during Egypt’s New Kingdom, which dated from 1550 BCE to 1077 BCE. The New Kingdom period is commonly called the Egyptian Empire. It was one of the most well-known phases of Egyptian history. The period encompassed the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth dynasties, ending with the death of Pharaoh Ramesses XI in 1069.

Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt reigned over one of the empire’s most prosperous times and created strong trade relations with regional powers.

During the eighteenth dynasty, some of the best-known pharaohs ruled Egypt, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, and Tutankhamen. It was a time of strength and stability for Egypt, with a great deal of power held by priests and religious leaders. The nineteenth dynasty, ushered in by Ramesses II, was marked by expansion. Under Ramesses II and his successors, Egyptian territory grew significantly in the east and south. But political intrigue at court weakened the tight hold on power enjoyed by pharaohs during the eighteenth dynasty.

During the twentieth dynasty, environmental factors and invasion from the Sea Peoples contributed to the Late Bronze Age Collapse. Pharaoh Ramesses III’s reign lasted from 1186 BCE to 1155 BCE. During this time, the Sea Peoples attacked Egypt. Although Ramesses III defeated the Sea Peoples and made them subjects, the cost of the two battles on both land and sea led to an economic downturn. Around 1140 BCE, environmental issues that could have been caused by a volcanic eruption caused diminished sunlight. Food shortages soon followed. Food rationing and labor strikes further undermined central authority.

After the death of Ramesses III in 1155 BCE, his sons fought over control of Egypt. The existing food shortages escalated into famine due to droughts, fueling civil unrest. Shortly after Ramesses XI took the throne in 1107, Egypt was effectively divided into Upper, Middle, and Lower Egypt. All were ruled by de facto leaders. His death in 1070 BCE marked the end of the New Kingdom and the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period. This was a time of unrest and decline for Egypt.

The Third Intermediate Period dates from 1069 BCE to 664 BCE, making it the primary period during which Phoenician trade routes were active. The period was marked by instability. Foreign invasion was common and power shifted away from kings to priests. The former empire was divided between warring rulers, and new kingdoms were established across Egypt. Between 1100 BCE and 700 BCE, Assyria replaced Egypt as the leading civilization of the Near East. In 670 BCE, Assyria invaded. In the mid-600s BCE, Psamtik I ushered in a period of stability that lasted for nearly a century. But the rise of the Persian Empire threatened the reunited Egypt, and in 525 BCE the Persian king Cambyses II defeated Psamtik III to become pharaoh of Egypt.

Anatolia

Anatolia, which covered much of modern-day Turkey, was ruled by the Hittites from around 1600 BCE to 1180 BCE. Prior to Hittite control, Anatolia was controlled by the Akkadians and the Assyrians. Both cultures were based in Mesopotamia. The Hittites, on the other hand, centered their empire in Anatolia. Their capital was at Hattusa, which was established as their seat of power in around 2000 BCE. The empire they established, called the Hittite Old Kingdom, would eventually control most of Anatolia, or Asia Minor.

Anatolia, in modern Turkey, was a powerful civilization during ancient times. Anatolian art, like this figure, influenced Phoenician art because Anatolians traded with the Phoenician city-states often.

Although there is some debate about who the first king of the Hittite Empire was, most accounts consider Labarna I as the founder of the Old Kingdom. He was the son of PU-Sarruma, about whom we know nearly nothing other than the fact that he was an early pre-empire king of the Hittites. “Labarna” went on to become a title for Hittite kings, leading to some confusion over the naming of other rulers. Under Labarna I, his successor Hattusili I (also sometimes called Labarna II), and Mursili I, the Hittites waged wars of conquest against the Levant and Mesopotamia.

Herodotus on Phoenician Trade

Herodotus is one of the most celebrated historians of the ancient world, and he lived between 484 BCE and 425 BCE. Here, he writes about the role of Phoenician traders in feuds between the Greeks and the Persians, including the capture of Io, the daughter of a Greek king:

According to the Persians best informed in history, the Phoenicians began to quarrel ... They landed at many places on the coast, and among the rest at Argos, which was then preeminent above all the states included now under the common name of Hellas. Here they exposed their merchandise, and traded with the natives for five or six days; at the end of which time, when almost everything was sold, there came down to the beach a number of women, and among them the daughter of the king, who was, they say, agreeing in this with the Greeks, Io, the child of Inachus. The women were standing by the stern of the ship intent upon their purchases, when the Phoenicians, with a general shout, rushed upon them. The greater part made their escape, but some were seized and carried off. Io herself was among the captives. The Phoenicians put the women on board their vessel, and set sail for Egypt. Thus did Io pass into Egypt, according to the Persian story, which differs widely from the Phoenician: and thus commenced, according to their authors, the series of outrages.

Herodotus was a Greek historian who wrote frequently about trade with Phoenicia, giving us some of the only accounts of the civilization.

Under Mursili I, the Hittites took control of Yamhad. This was a region of northern Syria with the capital of Aleppo. In 1531 BCE, Mursili I attacked Babylon. It was the farthest south a Hittite ruler had taken his army at that time. Although he did not conquer Babylon, historians believe it did end the rule of the Amorite dynasty and made space for the Kassites to take control.

Mursili I was assassinated in a coup when he returned to Anatolia. His death ushered in a period of unrest that eventually led into the Late Bronze Age Collapse. Under his successors, the Old Kingdom experienced civil unrest and a loss of central control. The Assyrians retook control of the territories in Syria that Mursili I had claimed. Little is known of this period of Hittite rule due to poor records and a rapid succession of rulers. Zidanta I followed Mursili’s successor. He ruled only for ten years before being killed by his son, Ammuna, who took the throne after his father’s death. It was during Ammuna’s reign that most of the Hittite territory outside of Anatolia was lost. Ammuna fought wars against cities that may have been in rebellion.

The trend of assassinations and unrest continued until the early fourteenth century BCE, when Tudhaliya I ushered in what is called the New Kingdom. Tudhaliya I strengthened central rule and expanded settlements while establishing good relations with neighboring peoples. He also reclaimed Aleppo in northern Syria and spread Hittite rule west. His successors lost and gained territory over the centuries, until 1180 BCE. Then the Late Bronze Age Collapse caused the dissolution of the Hittite Empire.

During the Late Bronze Age Collapse, the Hittite Empire was attacked and conquered by the Arameans, Luwians, and Phrygians. The Hittite capital at Hattusa was destroyed. Their territory was divided into smaller, independent states. Shortly thereafter, the Assyrian Empire claimed much of the area, with the Phrygians claiming most of the rest. For the rest of antiquity, Anatolia was held by various empires. First it was absorbed by Rome, and then it became the seat of the Byzantine Empire.