12

Everything I Know About History, I Learned from Doctor Who

Are You My Mommy?

Fact. Throughout forty years of time and space wanderings, the Doctor never once set foot in the years 1939 to 1945. Well, he did once, in The Curse of Fenric, although there the war is a chronological necessity in a tale that is more concerned with the distrust that existed between putative allies Britain and Russia.

And again in the Big Finish audio Colditz, the Seventh Doctor and Ace washing up in the grounds of the most notorious prisoner-of-war camp in the Third Reich and battling to prevent the TARDIS from falling into Nazi hands.

But that was all.

By contrast, since the show’s return, he can scarcely keep away from it.

A random sampling.

There was Let’s Kill Hitler (2011), a marginally prewar adventure set in Hitler’s own office—albeit one whose title turned out to be more captivating than the episode, with Hitler reduced to little more than a campy backdrop to the continuing saga of the Doctor and River Song.

There was The Doctor, the Widow, and the Wardrobe (2011), where the perils of the long-distance wartime bomber pilot were reduced to an emotional coat hanger for a revised visit to Narnia.

And there was Victory of the Daleks, a foolish rewrite of the Second Doctor’s Power of the Daleks that was rendered even more asinine by the deployment of a squadron of Spitfire fighter planes into outer space.

One of the great things about Doctor Who is that it asks, and often receives, a suspension of disbelief, a broadening of the mind, the opening of the imagination. But it usually offers something in return. A sense of reality within the unreality, science within the unscience.

One of the defining images of the Eleventh Doctor’s life span, reworking a World War II–style poster to celebrate Churchill’s greatest secret weapon.

It is not, and never has been, sufficient for the show to simply say “and then this happens” without explanation or exposition, because what is Doctor Who really? A well-honed drama penned by the greatest available television writers of their generation? Or a comic book drawn by a four-year-old, for whom anything is possible because he or she says it is?

Sometimes, just lately, it is hard to say. After all, the bundling of surprise development upon surprise development, without any reason for any of them, is scarcely a unique flaw in twenty-first-century television writing. Lost got away with it for six seasons.

So hey! The inventor is a robot!

Wow, the Daleks are recycling the same plan that failed in Power of the . . . , and hoping the Doctor won’t remember (and they were right. He doesn’t.)

Golly, the Doctor knows Winston Churchill.

And oh my giddy aunt! There are Spitfires in space!

Stop right there, please.

Because the sight of the Spits going out into the universe to battle Daleks on their own turf remains one of the least believable sequences Doctor Who has ever conceived, a crass manipulation not only of our understanding of the show, but also of our appreciation of the Spitfire itself, a totally one-sided exchange of storytelling nous for one more cheap thrill in a season that was sadly becoming increasingly reliant on such things.

History grabbed its coat and slipped out the back door.

Turn to Page Seventeen in Your Textbook, Please

It wasn’t always like this.

From the outset, Doctor Who was never intended to be simply a science-fiction program. Rather, it would utilize sci-fi to enable its cast to interact with our own planet’s past, hurtling back to key dates in history to introduce viewers to the movers and shakers of the age. Arguably, the first story, 100,000 BC, could be said to fall into that category, what with all the cavemen and grunting, but truly, the program found its historical legs with the fourth adventure, Marco Polo.

The earliest Doctor Who adventure to have fallen seemingly irretrievable prey to the tape wiping terror, Marco Polo was also the first to throw itself wholeheartedly into the insistence that Doctor Who be educational as well as entertaining. To that end, the Doctor and his companions find themselves in thirteenth-century China, en route to the court of Kublai Khan in the company of Marco Polo, the famed Venetian merchant whose travels and writings did much to open up the Far East to Western minds.

As such, it is very much in the spirit of other period historical dramas, with the added dislocation of the travelers’ modern origins to remind us that we’re not simply watching a school television adaptation; and with the First Doctor’s sly humor and even slyer intelligence to wriggle the crew out of their latest dilemma—the loss of the TARDIS in a game of backgammon.

The First Doctor, sly humor and even slyer intelligence.

Photo courtesy of Photofest

It is this dislocation, and the resulting ability to play hard and loose with established fact, that raises Marco Polo above many more conventional TV retellings of his adventures (the 1982 miniseries, for example); excellent casting is apparent from the “telesnaps”—an astonishing collection of off-air photographs taken between 1947 and 1968 by a west London photographer named John Cura and sold commercially—while excellent dialogue survives in the audio recording, and the main criticism has to be that, at seven episodes, it goes.

On.

Way.

Too.

Long.

After the thrill of The Daleks and the drama of Inside the Spaceship, Marco Polo might have been a different show altogether.

It would not, however, be alone for long. Just weeks later, The Aztecs dispatched the TARDIS back to Earth and back to school, in an episode whose underlying story—the legitimacy and even possibility of changing history—is camouflaged beneath a gorgeously extravagant panoply of pre-Columbian robes and headdresses, human sacrifice, and grisly combat.

Exquisitely designed and cunningly plotted (and miraculously surviving intact to this day), it reveals Barbara—a history teacher, remember—to have a special fascination with Aztec culture, and The Aztecs is her opportunity to discover whether one of her own pet theories held any water; the belief that if the Aztecs had only abandoned the practice of human sacrifice, the invading Spaniards might not have been so quick to wipe them out.

It is a notion the Doctor agrees with in theory but cannot, of course, countenance in practice, and the resultant conflict between spaceman and school ma’am is one of the defining moments not only in their relationship with one another, but also in the Doctor’s relationship with time itself.

Unfortunately, his insistence that “You can’t rewrite history! Not one line!” is, of course, wholly dependent on knowing what that history will be—a conundrum that he will never resolve and that will, in fact, come back to bite him on many, many subsequent occasions.

Considering how little control the First Doctor appeared to have over the TARDIS, it does seem to have discovered a remarkable rhythm. Earth to alien, alien to Earth, alternating back and forth as though only by absorbing the travelers in the historical lessons of their own planet can they be expected to think freely enough to appreciate those of some far-flung galaxy.

The Reign of Terror transports the Doctor, Ian, Barbara, and Susan to France in the 1790s. The Revolution is in full swing, and with it the Terror, the seemingly random but wholly methodical hunting and execution of the former aristocracy by the barbaric hordes of Robespierre. Into this seething hotbed of conspiracy, insurgency, and counterrevolution stumbles the TARDIS, its crew seemingly predestined for a date with Madame la Guillotine, and an adventure that will summon up all their wiles before they can finally make their escape.

Four episodes of the original six-part broadcast still exist (the two errant segments were recreated using animation for the 2012 DVD release), and it’s a captivating yarn, cut very much in the style of a nineteenth-century G. A. Henty novel, with obvious nods to the Scarlet Pimpernel. Unfortunately, like the show’s other early historical meanderings, it is perhaps a little too aware of its educational duties to truly allow the story to take shape. It was certainly a very weak climax to the show’s first season, as Doctor Who moved into a six week hiatus (September 12–October 31, 1964) before returning with Planet of Giants, the return of the Daleks—and then marching on to a truly dramatic date with The Romans

The TARDIS turns up in ancient Rome, at the height of the reign of the Emperor Nero, and this time the entire cast, but Hartnell in particular, is on the lookout for humor in both script and setting. Wryly, too, the notion that the travelers should not interfere with history is given another nudge when we discover that it was the First Doctor who suggested that Nero burn the place down as an early example of urban renewal. Or, as the Tenth Doctor told Donna as they walked through Pompeii and she asked if he’d ever visited the Roman empire before, “Before you ask, that fire had nothing to do with me. Well a little bit.”

The TARDIS’s next port of call, historically speaking, was the twelfth-century Holy Land, at the height of the Third Crusade. And the fittingly titled The Crusade emerged a highly visual and very well designed production, hamstrung for the modern viewer only by the fact that two of the four episodes are currently missing. But with King Richard the Lionheart a stately presence at the heart of the intrigue, knights and Saracens locked in deadly combat, plot and counterplot piling high on one another, and all concerned having a jolly good time, The Crusade (like The Romans) is an example of what the show could achieve in a world without definable monsters.

The Doctor Bites Your Leg-Ends

From solid history to ancient legend, a visit to Homeric Troy, ten years into the Greek siege of the city, saw the Doctor, Steven, and Vicki renounce their status as simple travelers and (sometimes) observers, and become instead The Myth Makers.

The Homeric gang are all here—Achilles, Hector, Priam, Paris, Agamemnon, Odysseus, and Cassandra—in a tale that itself aspires to epic status, and effortlessly takes its place at the very apex of the show’s historical escapades. It is also one of the saddest, as Vicki—whom the Trojans have designated a prophetess and renamed Cressida—announces she will be remaining behind at the end of the story, to plight her troth to the warrior Troilus and take her place in one of the greatest love stories in history.

We, like the Doctor, will miss her; so much so that when Steven is wounded and the Doctor needs somebody to help carry him into the TARDIS, he turns to Katarina, a handmaiden of Cassandra, for whom death—for that is what she assumes has befallen her as the TARDIS wheezes into life—is just one more adventure to be undertaken. Her unquestioning calm and gentle beauty paint her as an ideal companion for the Doctor. If she is only permitted to live that long.

Of course, she isn’t. Katarina perishes in one of the subplots wrapped around The Daleks’ Master Plan, and her bereaved associates are so exhausted by their survival that even the Doctor needs a rest. It would be over forty years before a future TARDIS occupant, Rory, wondered whether the old box deliberately sought out trouble for them (in the novel The Silent Stars Go By), darkly imagining a halfway apologetic Doctor asking, “Didn’t I tell you about the Predicament-Seek-O-Matic Module?” But he probably wasn’t the first who thought that, and right now even the Doctor was tired of the turmoil. Time, then, for a break, and a visit to sixteenth-century France, so that he might consult with one of his favorite apothecaries, Charles Preslin.

Which meant there was nobody around to stop Steven from wandering into the tangled web of political and theological intrigue that pitted the Huguenots against the Catholic church and, in particular, the ruthless monarch Catherine de Medici.

The slaughter that French history (and the Doctor Who episode guide) calls The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Eve is about to begin, and the Doctor, to his evident dismay, is unable to halt the ensuing destruction. History must remain unaltered, the Huguenots must die. Just as the Clanton brothers must perish on the TARDIS’s next port of historical call, Tombstone, Arizona, on the eve of what the lore of the Wild West remembers as the Gunfight at the OK Corral.

The bad boy Clantons—Billy, Ike, and Phineas—were hot on the trail of the man who shot their fourth brother Reuben, at the time. Doc Holliday was the man they seek, but a Doctor of another kind altogether had recently arrived in town, in search of a cure for a tooth ache, and inevitably the bad guys got them confused.

What follows is Doctor Who more in name than nature, although that was a dilemma the show had long since grown accustomed to solving as it continued to push its historical epics against its growing reputation for monsters, robots, and interplanetary evil. By that token, The Gunfighters was no more or less preposterous than Marco Polo, The Aztecs, The Reign of Terror, The Romans, The Crusade, The Myth Makers, or The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Eve. Except for one thing. It was a musical.

Okay, not quite a musical in the Rodgers and Hammerstein, Busby Berkley way you’re probably thinking. But inasmuch as a recurring song, “The Ballad of Jonny Ringo,” rang through the story; and companions Stephen and Dodo were roped into a barroom performance of sorts, The Gunfighters can very easily be written off as “the one with the singing,” and both an enjoyable plot and some excellent acting get overlooked. In truth, it is its unpredictability and, yes, its daftness that render it quintessential Doctor Who. Particularly when compared with the Doctor’s 2012 return to that same era. . . .

The history lessons were coming less and less frequently now, and the lessons themselves were less and less exacting. The Savages (1966), for example, is more allegorical than historical, although viewed from today, the moralistic tone it adopts lines up so neatly enough against the political climate of the mid-1960s that many viewers regard it as a straightforward condemnation of colonization.

Many of Britain’s own Empire holdings had gained independence in recent years, against a backdrop of growing unease regarding the so-called Mother Country’s treatment of, and attitude toward, the native people of those lands. True, the real-life overlords never went quite so far as the story’s Elders—a technologically and intellectually superior race who maintain their own lifestyle by cannibalizing the life force of the people they refer to as savages. But still there was comment to be made and comparisons to be drawn, and the modern viewer’s main concern is to ensure the historical parallels do not overpower the story itself. Which, sadly, is not that difficult to do, for it is a slight little thing whose ultimate resolution, the appointment of an independent arbiter to ensure there are no further outbreaks of shenanigans, is little more than a band-aid, and a convenient way of writing Steven out of the series.

We were back on firmer historical ground with The Smugglers. Outraged to find Ben and his “dolly rocker Duchess” Polly have snuck into the TARDIS without so much as an invitation, the Doctor determines to teach them a lesson and simply launches the TARDIS off on another aimless jaunt.

They wind up in Cornwall, England’s bottom-right-hand corner, and that’s an impressive feat. But scarcely one that causes Ben too much concern. Just so long as he’s back on his ship by evening. It is only later, as they stop by a church to inquire of the nearest railroad station, that he discovers, as the Doctor suspected, that they have traveled back two centuries, into the midst of a local squabble among landowners, smugglers, excise men, and a handful of pirates, late crewmates of the legendary Captain Avery. The same Captain Avery who would make a return appearance in the life of the Eleventh Doctor in 2011 (The Curse of the Black Spot).

A rip-roaring tale redolent of J. Meade Faulkner’s literary classic Moonfleet plays out with much piratical banter, mistaken identity, and dastardly ne’er do wells, and also a fair amount of short-sightedness, for how else to explain why everyone seems convinced that Polly is a boy? In other words, it’s a classic, delivered with sufficient pace and élan that, though it currently exists only in audio, it still stands among the First Doctor’s greatest triumphs.

It was also his last purposefully educational voyage into Earth’s past. The TARDIS’s next journey took him to the Tenth Planet and his date with regenerative destiny, but old habits clearly died hard, for no sooner had the Second Doctor collected his wits and defeated the Daleks than he was stepping out onto the broad moors of the Scottish highlands and straight into the aftermath of one of the bloodiest battles ever fought on British soil.

The Battle of Culloden (Blàr Chùil Lodair) took place on April, 16, 1746, the final clash between the French-supported Scottish Jacobites (fighting for the right of the descendants of King James II to take the British throne) and the British Government of the Hanoverian King George II. The fighting lasted little more than an hour, and it was a slaughter. Around 1,250 Jacobites were killed, as many again were wounded, and 558 prisoners were taken and subsequently executed. The Redcoats lost 52 dead and 259 wounded.

Another excuse for the BBC’s Accents and Stereotypes department to get down and dirty with the dialogue, The Highlanders’ four-part festival of Hibernian hijinks avoids the bloodier elements of the battle to concentrate instead on a dastardly tale of the slave trade and defeated clansmen being shipped off to plantations on the other side of the world. The arrival of the Doctor, Ben, and Polly will put a stop to that, but as an illustration of just how thoroughly modern Polly is, she cannot understand why there should be such enmity between English and Scots. And people say falling educational standards are a recent phenomenon.

Ben and Polly, as always, shine through the story. Genuinely excited by the adventures into which they are being thrust on a weekly basis, their enthusiasm encourages the Doctor to treat them closer to his equals than any previous companions. It’s a double act, however, that had little time left in which to run. As the TARDIS leaves Scotland at the end of the story (which today exists only in audio), an extra companion is aboard, a young Scottish piper named Jamie McCrimmon.

The Highlanders was Doctor Who’s final unabashed journey into, and examination of, the historical past. The Doctor would still visit it, of course, and with an eye for detail too—the Fifth Doctor’s Black Orchid (1982) is a magnificent period piece, a truly Agatha Christie-esque murder mystery set in an English country house in 1925. But history and the TARDIS are more prone to interact directly with one another nowadays, conjuring up situations that have ranged from the sublime (The Unicorn and the Wasp, 2008) to the ridiculous (Timelash, 1985), and the noble intentions of the early years seem far, far away.

With one exception.

Well, Are You?

For almost eight solid months from September 1940 until May 1941, and intermittently for four years thereafter, German bombers paid almost nightly visits to London, unloading countless tons of high explosives onto the city in an attempt to soften the UK up for invasion. More than a million homes were destroyed, over 20,000 civilians killed—and that was in the capital alone. Other cities, too, were targeted; some were all but wiped out. There were a lot of children wandering around looking for their parents during those harrowing months.

The difference is, their voices were not usually transmitted through disconnected telephones, unplugged radio sets and untouched typewriters. And they did not transform everyone they touched into a gas mask–clad replica of themselves—which is what the Ninth Doctor discovered when he and Rose washed up in London at the height of the Blitz, to discover almost everybody wearing that same gasmask and demanding, “Are you my mummy?”

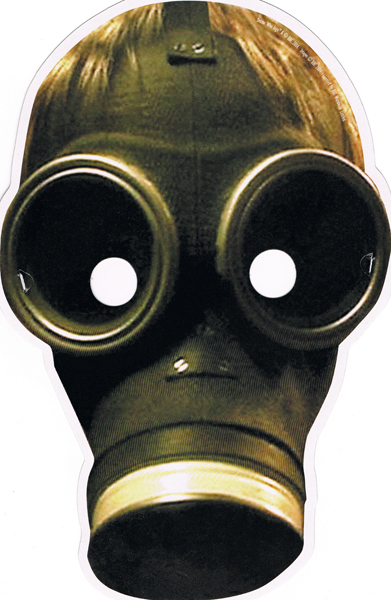

Even emptier than usual, a cardboard replica of a child-size gasmask.

It is one of Doctor Who’s most supremely creepy tales, yet The Empty Child/The Doctor Dances (2005) was much more than that. The story that introduced Captain Jack Harkness as an irresponsible, flirtatious, time-traveling ruffian was also the story that introduced one of the Doctor’s most tantalizing assistants-that-never-assisted, Nancy. More than that, however, it actually caught a flavor of what life must have been like through those long dreadful months; the uncertainty that started as fear but eventually slipped into resignation; the weary fatalism of living under the bombs night after night, until even the most unlikely scenario seems no more or less unusual than anything else you have experienced.

Including children whose faces had been replaced with gas masks.

No matter how many times you see it, The Empty Child/The Doctor Dances is still capable of sending a chill down the spine, and also a thrill of triumph. A war story in which nobody dies. A Doctor Who in which nobody dies. Even the Doctor celebrates that.