Introduction

Walter Ferguson was a farmer. He was in many ways like most other British North Americans in 1864. He had sixty acres of fields and a wood lot on the Rustico Road north of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Like most of his neighbours in the last days of that sweltering summer, he had no intention of missing the biggest show in decades. The Olympic Circus from Philadelphia was in town. The show was advertised as having acrobats, trick riders, clowns, dancing dogs, and performing monkeys. Walter had never seen anything like it, and he was thrilled that his family would have the chance to see such an extraordinary performance. The only other circus to come to Prince Edward Island had visited over twenty years before, and in those days his family couldn’t afford to take the time off or pay the price of a ticket.1

Like most Islanders, seeing the circus meant a small financial sacrifice on Walter’s part. The Fergusons weren’t poor, yet Walter knew that if he took the whole family, he’d have to find the money somewhere — which was fine. His old coat could probably last another winter.

At nine that September morning there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. It had been a hot summer, and today was going to be another scorcher. Walter straightened his draft mare’s handmade harness and bellyband and cinched her securely to the farm wagon. If it got too hot he’d have to stop and water the horse half way to town. Even with the water stop, they would get to town with a little time to spare. With everything ready, Walter helped his wife and the remaining five children up onto the open wagon.

The Fergusons were frugal people. Early this morning, Walter’s wife, Ruth, had packed their lunch in a wicker basket. The road to Charlottetown was heavily wash-boarded at this time of the year — but with luck, the wagon shaking from the dirt road wouldn’t break the wax seal on the two jars of glass-stoppered pickles. It would be a shame to have their sandwiches ruined. The damp tea towels that had been wrapped around the pickle jars would help a little to protect them. The cold tea made the night before was safely corked inside thick glass bottles. It was going to be a wonderful day.

The Olympic Circus took place in Charlottetown at the same time as the conference for the union of Britain’s North American colonies. Like most Canadians, Walter had only a passing interest in grandiose politics of the kind that involved the politicians in Charlottetown. As things turned out, the conference passed without much to-do. The politicians worked out the conditions for what would eventually become a united Canada, and Walter’s family loved the circus.

Walter would not find himself a Canadian citizen until 1873, when P.E.I. finally joined Canada. By then, the country stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific and, while he had a great deal in common with his compatriots in the other provinces, the regional circumstances of each of the future provinces differed in many ways. And although conditions varied in each region, each colony shared a common economic rationale for joining a Canadian union: by themselves, the regions were just too small to exist independently. They needed one another, and their differences were not nearly as large as the ones that existed between themselves and the Americans or British.

Canadians differed from Britain and America in many ways. Canadian society varied in terms of class, its economic basis, regionalism, cultural outlook, its security issues, and its levels of urbanization and industrialization. Canadians treated minorities differently than the British and Americans. Canadian attitudes to the arts, public institutions, education, the role of tradition, and the nature of civil society were all substantially different than those of the British and Americans.

During the Confederation decades, Britain’s North American colonies were outwardly quiet, seemingly stable, and relatively peaceful. Although the American economy was booming, America was reeling from the human and material costs of a devastating civil war, as well as struggling with massive economic reconstruction. The United States had already eclipsed Britain in terms of population and manufacturing output, while the British “mother country,” on the other hand, was, throughout the Confederation era, newly industrialized and caught up in the fervour of the fastest and largest imperial expansion in history. Amongst all three countries there were shared similarities, but there were also massively dissimilar features and circumstances at play.

Perhaps the most important differences were that Britain’s North American colonies had a small population and were geographically isolated. America, in contrast, with a surging population, was ten times larger than the colonies. As a result, in British and American eyes, Canada was relatively insignificant. It was a small, peaceful, colonial dependency, perched on the edge of the wilderness. Yet, as result of this very detachment, the colonies were growing, forging their own character with unique ideas, customs, institutions, fears, and aspirations.

There were common features shared amongst Britain’s North American colonies, but each had its own unique character; and at the outset of the Confederation decades, the very thought of joining them together to form one truly independent country straddled the borderline of being disloyal. Few Canadian citizens actually considered Canada as a full-fledged country. As late as 1891, in a burst of imperial zeal, John A. Macdonald proclaimed, “A British subject I was born, a British subject I will die.” Decades before, in making the case for Confederation, he was unequivocal as to how he envisaged Canadians being “a subordinate, but still powerful people.”2

Most Canadians, before and after Confederation, regarded the country as “a self-governing British colony”3 — about as incongruous a description of independence as one can imagine. Canada certainly had some degree of independence, but as a country it was willingly subordinate to its wealthier and more powerful parent, letting Britain take charge in matters of defence and foreign policy, and have the ultimate authority over its laws. From today’s perspective, such an abdication of responsibility might seem a bit absurd and a touch juvenile, but given that Canada had no external enemies, was geographically isolated, and had a trusting nature, that kind of cheerful national adolescence was understandable.

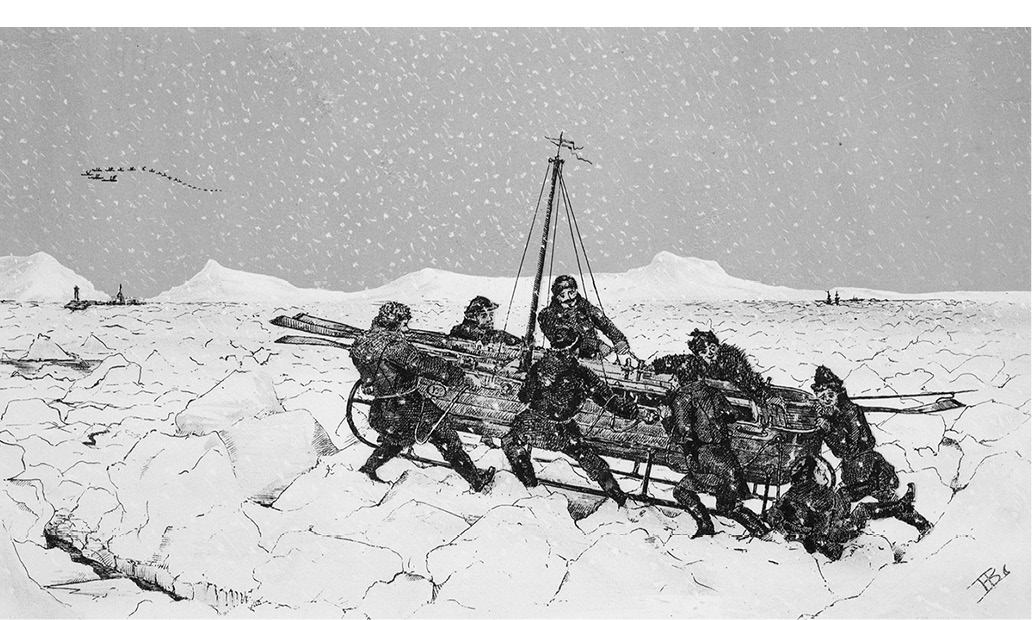

Getting the mail from mainland Canada to P.E.I. was often a struggle, as this illustration of Royal Mail delivery in the winter of 1867 shows.

The colonies that were to make up modern Canada were as peaceful as anywhere on earth. This is not to say the region was without problems. It was just that the inhabitants of Upper and Lower Canada and the Maritimes were much like Walter Ferguson. They led peaceful, relatively prosperous lives, and for the most part were optimistic about their future. The Canadian colonies had no serious external threats and were sheltered by what its residents saw as a benevolent and protective motherland.

As Canadians, we have often prided ourselves on this peaceful legacy, yet we should be careful not to be smug. Canada’s relative tolerance and prosperity has been more a product of chance than of any shrewd decisions our ancestors made.

Along with a small handful of other nations, Canada has been the beneficiary of tremendous good luck. Free from external threats and relatively self-sufficient, Canada has, for the most part, been an enormously privileged society. And despite several shortcomings, it has, through good fortune, progressed steadily toward realizing its potential. The creation of prosperous societies marked by compassion, fairness, and equality has been a slow and difficult journey for most of mankind. In this respect, Canada in the Confederation decades enjoyed several advantages over much of the rest of the world.