Chapter Ten

The Immigrant Peoples: The French

In the decades following the Quebec uprising of 1837–38, the province’s social and economic order began a steady but gradual transformation. This was due to several developments. Quebec’s rural society underwent a mild but prolonged crisis, one that had its origins in unsupportable population growth, outdated agricultural practices, and the social disruption that invariably accompanies demographic and technological changes.

The spectacular growth in the rural population between 1759 and 1840 imposed economic and social pressures on the old seigneurially based society. Not surprisingly, the province’s farms and villages had been unable to support the rapid population increase. Many of those who weren’t going to inherit their family farm moved into the cities, or joined the tens of thousands of francophone Quebecers who migrated to work for higher wages in New England’s factories.

Making things worse, arable land had also become scarce in the province. The soils on existing farms were showing signs of depletion, and crop yields were slowly declining. To further complicate things, farming methods had not kept up with modern practices and agricultural technologies were behind the times.

On the other hand, positive change did come about with the abolition of the seigneurial system in 1854. Farmers now had title to their own land. This was an enormous change in Quebec’s society, but it did not show immediate results. The economic effects of this development would take years to register, as the province’s farmers slowly but steadily accrued capital.

Other aspects of the economy were in a similar state of flux. The fur trade was in gradual but steady decline. The timber trade, however, was growing, and this meant that many French-speaking Quebecers found secure employment in the province’s booming forest industry.

Merchants’ houses, Pointe-Lévis, Quebec, early 1870s.

Rural French Quebec was not alone in facing the kind of upheaval that went along with industrialization. Similar issues were ongoing, or had taken place, in most European countries. In their analyses of social change in Quebec during this period, some historians have been defensive about the turmoil experienced in the province; however, in retrospect, we can see that these symptoms are normal indicators of the dramatic changes imposed on a society as it shifts from an agrarian to an industrial economy. What was extraordinary about Quebec was that the province’s evolution from a rural to a modern urban society was tranquil, gradual, and far less traumatic than that of the Irish or Scots immigrants who came to the country during the Confederation era — and certainly much more peaceful than most European nations. Quebecers faced nothing like the trauma that confronted Britain, France, Italy, or Germany during their periods of industrialization. As a rural, self-contained society, Quebec was lucky. The province was well-insulated from much of the painful social turmoil that marked the onset of the Industrial Revolution elsewhere. It was comfortably self-sufficient, while it remained politically and economically stable.

This is not to say that Quebec’s French-speaking population was a society without tensions. The rise of a small middle class, centred primarily in Quebec City and Montreal, prompted the growth of a peaceful but spirited conflict between the Church and the new bourgeoisie. The new French-speaking middle class was a small one and arose mainly from the province’s liberal professions: notaries, doctors, and lawyers, as well as a small but growing class of successful urban merchants. From this new middle class emerged liberal ideas and attitudes that challenged the old system.

The Parti Rouge became the political embodiment of this new kind of thinking. As a social movement, the Parti Rouge had its distant origins in the wake of the rebellions of 1837‒38, and in a uniquely Quebecois institution, the Institut canadien in Montreal. Because Montreal did not have a university at the time, a group of the city’s new middle class established the Institut in 1844. The Institut was founded to serve the city as a kind of literary and debating salon as well as a scientific association. Its members were free thinkers, and most were deeply worried that, with the union of Upper and Lower Canada, their French identity and future would be swamped; as such, they were strongly opposed to the new political order.

Les Rouges had several other issues on their agenda. They were the political spur for the abolition of the seigneurial system; they demanded universal suffrage; and they agitated for the province to have its own elected legislative council, judges, and governor general. Many of the Parti Rouge’s members wanted immediate commercial reciprocity with the United States, while some advocated outright for the province’s annexation by the United States. Most tellingly, they promoted secular education and were vigorous advocates of the separation of church and state.

All these views naturally brought them into opposition with the Tories and other conservative elements in society, but their fiercest opponents were in the Roman Catholic Church.

During the Confederation era in Quebec, the Catholic Church’s role and importance grew considerably. It is impossible to say what precisely caused this, but the ideas emanating from the Institut canadien and the formation of Les Rouges as a political force certainly acted as stimuli to the Church taking a more active role in the province’s political life.

However, Catholic influence in Quebec was not just political. There was a profound deepening of religious conviction in Quebec during the Confederation era. Between 1840 and 1896, church attendance for francophones in Quebec increased dramatically, from 40 to 98 percent. With religious observance skyrocketing, the Catholic Church also saw an enormous growth in the number of clergy and an unprecedented rise in the number of religious orders and institutions established in Quebec. During the Confederation era, eighteen new major congregations of brothers and nuns sprang up in the province, and the total number of priests in Quebec grew by 800 percent.1

During these years, a religious school of thought called “ultramontanism” gained acceptance within much of Quebec’s Catholic clergy. Ultramontanism had its beginnings in Europe, and was largely a response to the Church’s diminished influence following the wave of secular revolutionary fervour that swept France during the French Revolution. The central tenets of ultramontanism were the supremacy of religious authority over civil society and the doctrine of papal infallibility in matters of faith and morals. Ultramontanism didn’t begin to take hold in Quebec until some three-and-a-half decades after its appearance in Europe, but when it did, conflict between the new generation of free thinkers in the Institut and the Catholic Church was inevitable.

The Church was bitterly opposed to virtually all the ideas coming from the Institut canadien. For its part, the Church in mid-nineteenth-century Quebec saw the existing political system as entirely satisfactory. It left the Church in the key role it had played since 1759. It was not only society’s paramount moral authority, it was the champion for French-language rights and French culture, and it maintained the system of confessional Catholic schools. The Institut canadien posed a deadly threat to this system. Its members openly challenged the Church’s assumption that it was the overseer and watchdog of the province’s moral standards and not one’s individual conscience. Eventually, after years of bitter public argument, the Bishop of Montreal decreed that, under pain of excommunication, no Catholic could belong to the Institut while it taught “pernicious doctrines” and its library circulated banned books that were anti-clerical in nature. The Bishop of Montreal was eventually forced by the Vatican to retire for his involvement in secular politics, but the threat of excommunication was a body blow to “radical” thinking in the province. Over the years, the Institut’s membership and activities steadily decreased, and the Institut finally closed its doors in 1880. Les Rouges eventually softened their political doctrines, and, adopting a more practical compromise with the rest of Canada, they in turn joined the “Clear Grits” to form the Liberal Party of Canada.

While the Church in Quebec during the Confederation era was well-known for its forays into politics, it generally gets much less credit than it deserves for its important social work during the time. The Church in Quebec was heavily committed to, and invested in, education, health care, and charitable work. Unlike in Britain or in America’s newly industrialized cities, Quebec’s cities avoided many of the cruelest aspects of Victorian life. Life in those cities was certainly no paradise, but Quebec’s social evolution was much less harsh and exhibited fewer of the kinds of evils Charles Dickens described during the era. The poor got some elementary schooling; orphans were not left to roam the streets; the problems of the corruption and exploitation of children were not as great; and the province had fewer class issues and conflicts between those with newly acquired wealth and the growing urban proletariat. The Catholic Church essentially provided virtually all of Quebec’s social services. Schools, hospitals, homes for the destitute, asylums, orphanages, and almost all public charities were run by the Church — contributing substantially to the betterment of Quebec society at virtually no cost to the government.

Canada’s second largest French-speaking community, the Acadians, experienced a demographic resurgence during the Confederation era. With families frequently having a dozen or more children, the Acadian population jumped with each generation, growing from 8,500 at the turn of the century to over 140,000 by 1900.2

Acadian history in the Maritimes had until the nineteenth century been tragic. In 1713, the Acadians became British subjects after the Treaty of Utrecht ended the War of the Spanish Succession and the Acadian colony in Nova Scotia was ceded to the British. For forty-two years they lived peaceably as reluctant British subjects, but in 1755 they were forcibly expelled from their homes in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick.

The expulsion order was given by Charles Lawrence, the British governor in Halifax during the Seven Years’ War. The war in the Maritimes had largely been a desultory conflict, consisting of a series of small-scale raids and alternating attempts by the French and English to seize one another’s forts. After the British discovered nearly three hundred Acadian militiamen defending Fort Beauséjour in New Brunswick, Lawrence ordered Nova Scotia’s French population to be forcibly deported and their lands and goods seized. There was no credible strategic rationale behind the expulsion, as the Acadian farmers posed no military threat. However, Lawrence ordered the expulsion when the Acadians refused to take an oath of loyalty to the British.

The more plausible motive behind the mass deportation was that envious English-speaking colonists from the Boston area influenced Lawrence. A vocal group of New England colonists had long argued that the Acadians were an “alien” people living in British lands, and for several years they lobbied to take over the Acadians’ cleared and fertile farmlands. The militia volunteers and the loaded wording of the proposed oath gave them the excuse they had been seeking. Approximately ten thousand Acadians were deported, and several thousand others escaped to Quebec or hid in the woods. As soon as the Acadians moved out of Nova Scotia, settlers from New England began to move in.

In 1764 the expulsion order was lifted, and from that point right up until 1820 a stream of Acadians returned to the Maritimes. This time, they settled in Cape Breton, P.E.I., and northeastern New Brunswick.

The nineteenth-century Acadian resurgence has been called the “Acadian Renaissance.” Not only did the Acadian population soar during the Confederation era, but in this period they rediscovered an enduring sense of pride and identity and began to actively assert their political will.

Initially, after their return to the Maritimes, Acadians were distrustful of their neighbours and did their best to shun most kinds of contact with their fellow anglophone citizens. In the first six decades after the return, Acadian communities were relatively isolated, self-reliant, economically withdrawn, and inwardly focused, surviving largely on a subsistence basis. By the Confederation era, that began to change.

The Maritime provinces were self-governing colonies, and, by excluding themselves from the political process, the Acadians realized that, despite their increasing numbers, their interests and voices were not being heard. More alarmingly, their leaders realized that in a changing world, unless they changed and changed quickly, they would soon be assimilated. Local leaders in the three provinces stood for election to the colonial legislatures and quickly became a force to be reckoned with — and in doing so further fanned nationalist feeling.

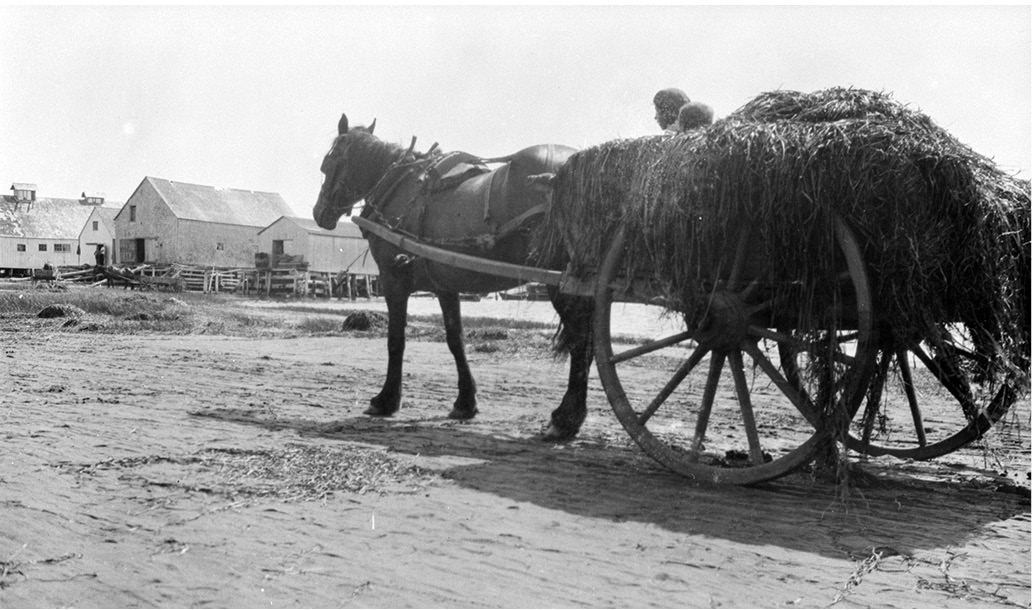

A kelp wagon on an Acadian farm, Nova Scotia, 1870s.

Somewhat like in Quebec, but less obtrusively in the Maritimes, the Catholic Church played a key role in nurturing pride and leading the Acadian nationalist movement. In 1864, the Collège Saint-Joseph, (the forerunner of the University of Moncton) was founded as an Acadian post-secondary institution. The Collège was to become a key factor in molding leaders and moving the Acadian cause forward. In 1880, after attending a St. Jean Baptiste conference in Quebec City, the Acadian delegates came home inspired by Quebecois pride, but also more than ever determined not to be assimilated into Quebec’s larger French-Canadian culture. In subsequent conferences of their own, Acadians approved the adoption of their own national anthem and a flag based on France’s tricolor with the addition of a gold Papal star. That tradition of holding conferences and congresses to advance common Acadian issues continues to this day.

Since reasserting their national pride and unique culture during the Confederation decades, Acadians have never looked back. Far from being assimilated, by building upon traditions of self-respect, forebearance, and hard work, their culture and institutions have flourished. In preserving their way of life and heritage, they have been a peaceful example to the world of what can be accomplished through dignity and patience.