Chapter Thirteen

Rural Life

Throughout the Confederation decades, Canada was primarily a nation with an agriculturally based economy, and the vast majority of its farms were small, family-run holdings. During this period, most of these farms gradually evolved from being subsistence-level operations to more profitable and sophisticated operations. As farming improved, surplus agricultural output grew, and as production increased, rural populations became an increasingly important political force.

Agricultural improvements during the era were the result of several factors. Agriculture itself was becoming a more specialized occupation. With the growth of mass manufacturing and higher education levels, farm machinery and farming methods were improved appreciably each year. With more and better railways and a growing road network, heavier machinery could be transported to more remote areas. As a result, newer, heavier ploughs, reapers, mowers, and threshers came into common use, and farmers could cultivate much larger acreages — all of which increased national agricultural yields.

Nonetheless, during the Confederation era, the standard of living on farms varied considerably. In areas that were being settled, it was not unusual to find farm families living, at least in the early years of their homesteading, in conditions that would have been the norm for settlers just before the War of 1812. This was despite the fact that, during the four core decades of the Confederation era, farming methods and equipment improved by leaps and bounds. For example, single-sided ploughing, which used the old, single-bladed ploughshare traditionally pulled by an ox or a horse, gave way to ploughing with self-sharpening, multiple-furrow ploughs. These were later replaced by circular-disc ploughs that were made out of much higher quality steel. By 1880, most farms in Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces were operating on a par with their counterparts in Europe and the more settled areas of the United States; but it was still not unusual for new settlers who had little money to use the methods and the machinery of a previous generation.

As farming methods improved, farm lifestyles began to change as well. Yet throughout this period, the underlying farm culture in Canada remained fairly constant. The major cultural shifts in rural Canadian society were still several decades away. Farm and village life would not undergo a major transformation until the First World War.

One of the distinguishing constants of farmers in all the countries of the New World was that for them it was vitally important to own their own land. Unlike Europe, where farmers tended to be tenants on properties owned by members of an upper class, Canadian farmers, even if they were poor and struggling, were landowners; and with freehold ownership came a different and more independent outlook. Canadian farmers did not view themselves as an underclass. They saw themselves as dignified, self-sufficient, and independent. Paying rent for farmland was not considered to be shameful, but it was not what families aspired to. Independent land ownership was a key attraction and a source of intense pride. To achieve ownership, even during the more technologically developed later years of the era, new homesteaders would willingly live much like the early pioneers, with few comforts, considerable hardship, and tremendous risks.

The first trickle of East European immigrants began in the Confederation decades. They were followed in later years by a flood of hardworking and capable farmers. These Austro-Hungarian women are on a hardscrabble Ontario farm in the early 1880s.

Risks of many different kinds were a constant factor in the lives of Confederation-era farmers. Weather, crop and animal diseases, sickness, or injury could be critical factors in the success and prosperity of a family farm. One year a farmer could find himself with bumper crops and surplus income, and the next they could be plunged into hunger, debt, and poverty. As in Ireland and Scotland, potato blight in the late 1840s and early 1850s forced many farm families off the land or into penury. Frosts, droughts, and insect infestations were common and caused near-famine conditions in many areas. New settlers with small farms and limited livestock herds were particularly vulnerable. In many cases, the smaller landholders were the ones seeking additional employment in nearby towns or in the timber business.

The poorest settlers were those in the newly settled areas. They lived closest to the land and built log or sod houses. They had few comforts or amenities. In the more-established areas, farm houses were much more elaborate and comfortable, usually well-furnished, and often built from quarried stone, brick, or timber. In the 1840s, it was not unusual for pioneer settlers to live in traditional log cabins. Those first houses and out buildings would most frequently be built in a matter of days with the assistance of nearby community members. Most often, the buildings on these farms were temporary ones, usually only a single-storey hut, a square metre or two, with an angled lean-to–like roof. In the early years, doors would be slabs of timber, often on leather hinges, and windows would be simple openings covered by a rough shutter. Fireplaces were made from stone and chimneys were built from mud, stones, and sticks. Fires were not uncommon, and in winter they were often fatal.

The earliest farm houses were drafty, cold, crowded, and unsanitary. If a dirt floor was not used, the houses’ first floors were made from roughhewn timbers. Furniture might consist of a homemade bench, a simple table, and a shelf or two to hold whatever pots and utensils were on hand. When a farmer first built his house, one side would often be reserved for his family, and if he had time before winter, the other side for his animals. By the second year, a farmer would have assembled a second shelter and perhaps a corn crib to store his crops: corn, wheat, hay and any root vegetables that he had grown. Perhaps by the third year, if things had gone well, he would build a separate livestock barn. All these out-buildings would have been carefully positioned so that they provided the farmhouse a break from the prevailing wind.

Most farmers’ standard of living improved dramatically in the first decade on the land. Confederation-era settlers were industrious people, with a work ethic that today might be regarded as compulsive. Throughout the year, they worked day in and day out and their farms improved quickly. Occasionally, some farmers would remain in the original building as a means of paying reduced taxes, but most quickly added larger structures to those first houses or turned them into barns or animal shelters.

As farm houses improved, one of the first purchases farmers made during the Confederation decades was a new iron stove. Stoves came in many sizes and degrees of complexity. Their great advantage was that they were infinitely more efficient than open fires, used less fuel, and distributed heat much more evenly. Farm stoves made heating, cooking, and laundry chores much easier. They also meant that different kinds of meals could be prepared, and in this respect they not only contributed to comfort and convenience, but they made the farmers’ diet more varied and interesting. The growth of iron mining in North America in the 1820s led to the development of precast, multi-purpose iron stoves. The first stoves in Canada were imported from Britain, but later were manufactured in the same foundries in Quebec and Ontario that built steamboat engines for the Great Lakes.

In addition to heat, easy access to water was equally critical for survival on a Confederation-era farm. There were two methods that farmers used to procure adequate supplies of water. The first and simplest was to draw fresh water from a natural source such as a stream, creek, or river. However, most new farms were established some distance from existing watercourses and farmers had to dig wells. Since biblical time, wells had been hand dug and lined with either stones or bricks to keep them from collapsing. Most farm wells in Canada were dug by hand; however, in the 1830s, some wells were dug mechanically with a kind of iron boring post operated by a horse plodding along a circular track. Steam drills did not come into common use in Canada until the 1890s. In the later years of the era, wells were outfitted with galvanized iron pipes.

Dowsing or divining for water on farms was a fairly common practice throughout the Confederation era. Although, the typical dowser with a hazel or willow rod searching for water had no scientific basis, most professional water diviners had a well-developed sense as to where the water table lay. Wells typically would be dug near underground springs and streams that fed nearby watercourses — and it was not uncommon to dig numerous dry wells before finding a viable water source.

Although farmers might occasionally rely upon outside help for unique tasks — like locating a well — Confederation-era farmers were a self-reliant group and performed almost all of the work that needed doing on their farms themselves. Most of this generation of farmers were incredibly skilled people; and although we often consider their time a less sophisticated one than ours, we would do well to consider the range of skills these men and women had. Not only did they grow and prepare all their food, but they also built and repaired almost everything they owned. Farmers always had a collection of tools on hand for doing any and all repairs. Beside the barn, or next to the farmhouse, was often a small shed with the farmer’s tools: a carpenter’s bench, a vise, hammers, numerous saws, planes, chisels, perhaps a wood lathe, and woodworking tools with which they fashioned shingles, plough handles, oxen and horse yokes, leather work of every description, furniture, toys, and the bits and pieces required to repair a thousand broken or worn out items.

Despite their ingrained self-reliance, farmers all across Canada frequently relied on each other. Indeed, there was a communal aspect to Confederation-era rural life that has almost entirely died out in modern society. Across the country, it was not uncommon for neighbours to assist one another on projects, often devoting weeks at a time to an activity. It was a shared, freely provided kind of interdependence among neighbours that is almost alien to modern sensibilities. One such tradition that has all but disappeared in our times is the barn-raising bee.

Barn raising was a shared, voluntary, community effort where people came together to build or repair an individual’s barn. Barns were immense structures. They were the period’s largest element of rural infrastructure and were an essential part of every farm. The energy and time required to build one was completely beyond the means of any one family, and so each family relied on the larger community to help them. Even with an entire community’s help, building one was a daunting task, especially for a novice farmer.

Barn raisings became a characteristic part of life. No debts were incurred for the community’s work. No one was ever paid for their services, and virtually everyone in a community was expected to volunteer when a barn had to go up. Petty grievances and personal squabbles were put aside as everyone pitched in to get the work done. Barns could not be built without the efforts of hundreds of men and their families working together for the one or two days it took to get them put up. However, the preparation that went into raising a barn would often take a year or more of backbreaking effort and scrupulous planning.

Months before the actual day of the barn raising, farmers would plan the location, size, and layout of the building. In an era before cranes or any sort of heavy-duty engineering equipment, barn design and planning was a task requiring unique skills, aptitude, and ingenuity. There were few architects or professional builders in rural Canada, and planning for the barn’s design was usually a group effort drawing upon the expertise of several men. The year before the barn was built, the owner of the new barn would seek the advice of several experienced community members. The most knowledgeable barn builder would usually be designated as the foreman. Once a design had been agreed upon, trees would be felled, timber cut and milled, pegs and dowels carved, buckets of nails forged, stone foundations built, ropes prepared and coiled, beams and planks numbered, notched, and marked, and all the additional materials carefully laid out days before the community descended on the farm.

A large, well-to-do family with servants on the lawn of their house. Eastern Townships, Quebec, mid-1860s.

Most barns were erected within a day or two in June or July. These months allowed farmers sufficient time to do the job between planting and harvest, and the weather would likely be favourable. Women in the community worked for days baking and preparing enormous quantities of food: roasts of beef and lamb, chickens, venison, pies, breads, and salads, as well as quantities of cider, beer, and tea. When the barn was up, it was traditional to hold a dance in the new building. Barn raisings knitted communities closer together, and because people had to get along, they served as a means of ensuring civility and respect within the community.

In addition to the man-made infrastructure of the Confederation-era farm, the land itself took considerable care and attention. For a settler, clearing the land was an enormous task. This was a time before the chainsaw, and removing the trees from a section of farmland was a staggering task. In New France, farmers with an axe could clear an acre and a half a year. By 1840, with better saws and improved animal harnesses, Canadian farmers could manage four to five acres a year.

Once the trees were felled, farmers had to deal with the issue of stumps. Stumping was a huge problem. You could not effectively plough a field full of stumps. Left to itself to rot away, a hardwood stump might take fifty years to disintegrate before it could be ploughed over. Confederation-era farmers got rid of their stumps in several ways: controlled burns, pulling them with a team of oxen, and massive, purpose-built, stump-pulling tools that made use of a screw-type device and a horse that uprooted the stump. Stumps pulled from the ground with their star shaped web of roots were often laid side-by-side and used as highly effective fencing.

Clearing fields of stones and stumps remained a major undertaking in the Confederation decades. Here, farmers use a modified buckboard and levers to move a granite boulder from a farm field in 1870s Ontario.

Much later in the era, dynamite was used to get rid of stumps. Dynamite, effectively positioned, made short work of the most massive stumps. However, there was one serious problem with dynamite — it required great skill to use. Dynamite could be bought relatively cheaply in a general store, but few farmers were trained in its use. Horrific farm accidents with dynamite were commonplace.

Though dynamite had replaced the use of oxen in stumping by the late 1860s, it would be some time before animals were replaced on farms more generally. Indeed, one of the major differences between Confederation-era farmers and modern farmers was their dependence on animals as a source of mechanical work. In the early Confederation decades, oxen were one of the most common animals used by farmers. Oxen (castrated male cattle) were used for their size and strength to pull and haul things such as ploughs or heavy wagons.

Confederation-era farmers found oxen useful for several reasons. An ox’s horns continue to grow throughout its life, which means that the animal is able to develop a wide spread of horns, which helps to keep their yokes from slipping off their heads. As well, oxen have a more reliable temperament than horses or mules, the two other most common farm utility animals of the period. Oxen are generally steadier and more consistent out in a farm field, and are less likely to bolt when startled. Oxen also have the added practical benefit that when their useful mechanical life is over, they can be eaten. However, oxen tend to live shorter lives than horses or mules. Oxen live for about ten years, compared to an average twenty-year lifespan for horses, and thirty-five years for mules.

However, largely for reasons of economy, oxen were initially the more popular animals in Canada. While horses can move much faster than oxen, they are also much more expensive to feed. And, unlike oxen, horses, for cultural reasons, have rarely been eaten by Canadians. Despite all these advantages and disadvantages, horses were consistently the more common draft animal in the United States during this period.

As the design of farm equipment improved throughout the Confederation era, teams of horses were increasingly used instead of oxen. With the advent of multi-bladed ploughs and discs, using a team of horses meant a farmer could cultivate far more ground and thereby drastically increase the productivity of his farm. Mules, on the other hand, which are the sterile offspring of a male donkey and a mare, are far more intelligent, stronger for their size, and more patient than horses, but because they could not be bred, they were never widely used in Canada.

Canadian horses played a significant role in the American Civil War. Canada bred several large, reliable varieties of horses, and sold tens of thousands of them to the Union Army for use as artillery draft horses and cavalry mounts. Without a steady supply of these strong, dependable horses, the Northern war effort would have been seriously hampered. But it was not just the horse breeding business that did well during the Civil War. Farming in general in Canada benefitted enormously from a lucrative export trade, as the North imported large quantities of Canadian food stuffs throughout the conflict.

Another key element of rural life that has all but disappeared today was the rural mill. Mills played an overlooked but important role in the Confederation-era’s rural economy. Mills of all sorts ground grain, cut wood, and spun wool, and they were a common feature of the Canadian rural landscape. In eastern Canada, mills were most often built on rivers, and tended to be, as in early Quebec, situated within a day’s wagon ride from farming communities. Because farmers travelling to a mill needed a place to eat and sleep, towns and villages frequently grew up around the mill. Since farmers brought their produce in wagons, livery stables and blacksmith shops also sprang up close to the mill, as did general stores, churches, and schools.

In western Canada, small mills did not play as critical a role in the development of the region, as railways brought grain to larger industrial-scale mills. Instead of the mill, the predominant feature of a prairie village was the grain elevator. Grain elevators did not come into use until very late in the Confederation period, with the first ones being purpose-built in Manitoba in 1879. They soon became a characteristic feature of every village.

A standard establishment in Confederation-era rural villages was the country general store. The general store was more than simply a retail outlet that sold a wide variety of goods, and the store owner and his wife were much more than just retail clerks. The store owner was a man of considerable importance and power. His store was one of the most important institutions in rural society. Not only was it a store, it also served as a social focal point. People would gather at the store when in town to exchange gossip and information. It also served as the post office, and, in some cases, the telegraph office. And for the community’s hired hands, those single men who worked seasonally on the farms and often had no other place to go than a bunk house to socialize, it became the only alternative to the tavern.

The general storekeeper was a man of considerable economic importance in early Confederation-era rural life. The storekeeper decided whether or not to extend credit to farmers who needed his goods, but were unable to pay until they sold their harvest in the autumn. As a creditor, the storekeeper was common right across the country. In Newfoundland, the general store bought the catches and set the prices for cod and seal. In the Maritimes, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies, and British Columbia, the storekeeper not only extended credit, but determined what kinds of goods would be available. In many ways, they became the arbiters of fashion and taste in a rural community, as all store-bought clothing, spices, sugar, hand tools, medicines, tea, coffee, dry goods, hardware, textiles, and glass came across the storekeeper’s counter.

Rural life in Canada during the Confederation decades certainly entailed hardship and privation, but in comparison to much of the rest of the world, Canadian farmers and their families lived well. The climate was certainly harsh and unforgiving, the work was exacting and unending, but the soils were generally fertile, food was abundant, the country was at peace, and, despite the changes of the period, life was settled, reassuringly predictable, and rewarding.

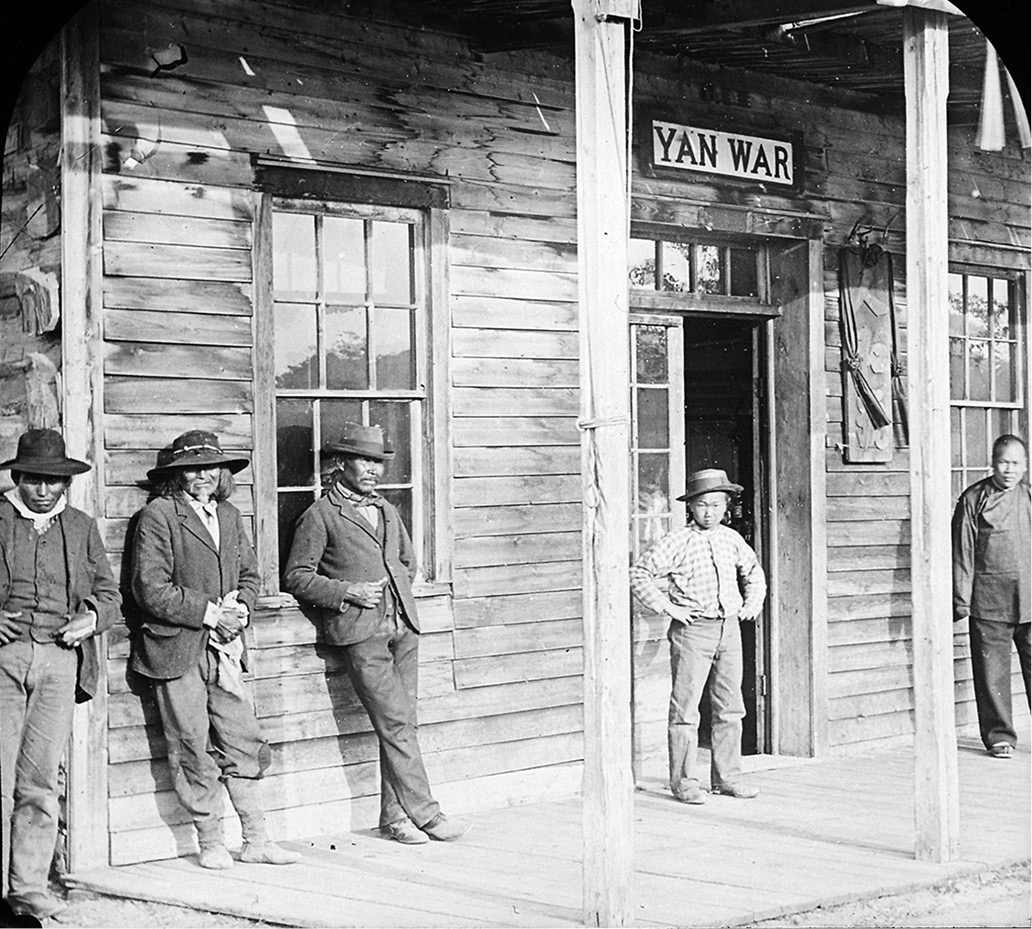

An early general store in the B.C. interior. This one was notable for being owned and managed by recent Chinese immigrants. General stores of the period often served as druggists and post offices — a phenomenon that seems to be repeating itself in twenty-first-century Canada.