Chapter Fifteen

Domestic Life

Domestic life in the Confederation era was in many ways uniquely Canadian. The nature of the family was changing more slowly than in other societies. Roles within the family were shifting gradually, and the manner in which people celebrated the significant events in their lives had become more complex, more elaborate, and, in some ways, considerably more bizarre than they had ever been.

Domestic life had moved from the simple and practical dictates of a pioneering ethos to a more self-assured culture, one seemingly bound by strict conventions and a stern Victorian code of manners and morality.

Canada was in the process of transforming from a frontier society to a hybridized nation, one that was overwhelmingly rural and traditional, but at the same time was adjusting to the onset of industrialization. The country had a world view that was in many ways dissimilar to America’s industrialized northern states or Victorian Britain. As a society, Canada had not begun to industrialize on a large scale. The repercussions of the social problems and disparities that afflicted Britain’s manufacturing cities, and the massive trauma of America’s Civil War and its sudden industrialization, were all experienced vicariously in Canada. At the same time, Canadians were coming to grips with the fact that the wider world was changing and going through a period of major social and industrial transition.

Canada was a literate society and its people were well-aware of the new ideas and the shifting social structure of the times. It was also a country strongly influenced by large-scale migration from both America and Britain. As a result, many of the changed attitudes in the “old countries” were bound to show up in Canada, even if they did so in slightly different forms.

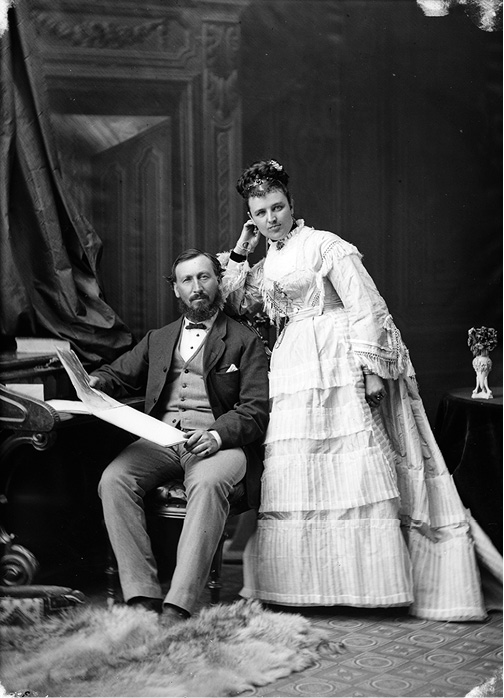

A married couple in Halifax, 1868. To keep their subjects still, photographers often tried posing them reading and staring with blank expressions. Slow shutter speeds and crude photographic plates caused blurring with the slightest motion. They also left future generations with the incorrect impression that their ancestors were stern and chronically morose.

Most Canadian families lived in a growing rural society that had only recently become prosperous. Although they were comfortable, their horizons were fairly narrow. Their culture and their situation offered few career alternatives to farming. Life on farms and in tiny villages meant that rural Canadians were relatively isolated and limited in their day-to-day range of personal contacts. Members of communities grew up, lived, and died knowing the same range of families and acquaintances throughout their lives. The practical alternatives available to men and women in choosing a life partner were limited. Most couples would have known one another quite well for several years before getting married.

Courtship in Canada’s rural areas was usually closely monitored. It was a process that began most often in church, at a social or a family celebration, and was subject to the rigours of Victorian respectability. Often a young man would have to ask the young woman or her parents for permission “to call” at a given time. Courting most often took place in the woman’s parents’ home, and in the initial stages would consist of a series of chaperoned visits. Later, perhaps, there would be the possibility of going walking, riding in a carriage, or sleighing together. In the mid-nineteenth century, formal love letters were often considered a romantic and normal part of the courtship process. There were books of instruction readily available advising young lovers on what to say, and if the process was still too difficult, it was possible to simply crib one’s lines from the manual.

After a suitable period of time, the young man would invariably ask the woman’s father for permission to marry his daughter. By the time of the Confederation era, arranged marriages were very much a thing of the past in Canada. Women certainly had to agree to a marriage, but nevertheless, the father of the bride normally reserved the right “to approve” a match. Parental approval was not just a one-way process; it was also a means of allowing an uncomfortable and stressed woman a reason to decline a suitor’s proposal.

Weddings during most of the Confederation era were relatively simple affairs, with only the closest of friends and family attending. This was true especially in rural areas. Lavish and more extravagant celebrations would become customary closer to the turn of the century. Brides wearing white became fashionable only after Queen Victoria’s wedding; and in Canada, the tradition only became commonplace in the late 1870s. Weddings were almost always held in the mornings, usually in a church, but sometimes in the bride’s or groom’s home. They would be followed by a small lunch or breakfast, with pieces of wedding cake and calling cards distributed as the guests left. The calling cards would advise guests as to when the newlyweds would be “at home” for visitors.

Given the restrictions in one’s marriage and career possibilities, and the reasonably uniform socio-economic nature of Canadian rural society, marriage was as much a practical choice as it was a romantic one. And once married, there was little scope for making any changes to the customary roles people played within the family. Within the framework of rural society, traditional family roles were well-established, and well-accepted. All the evidence suggests that there was little impetus to change them. Although there were courageous pioneers, women’s rights were not a prevalent issue. Men continued to be the breadwinners and women raised children and tended to domestic chores.

A newlywed couple, posed in front of Niagara Falls, 1870s. They were ahead of their time. The concept of a honeymoon vacation would not become popular in Canada until the late 1890s.

This was not a recipe for domestic misery, however. Canadian rural family life was based on practical but affectionate relationships — but in the event that there was little or no affection, these relationships were also buttressed by the dictates of loyalty and economics. Divorce was not a viable option for most rural families, and the financial realities of farm life were such that there were no other alternatives to keeping families together as viable economic units.

Getting a divorce was nearly impossible in Ontario and Quebec, as these provinces didn’t have divorce courts. If someone wanted a divorce, he or she had to make an appeal through Parliament, which was an option effectively open only to wealthy people who were willing to put up with the scrutiny and scorn that went with such an undertaking. The Maritimes had divorce courts, but the social and economic prohibitions against divorce were equally as strong there. And while it was possible to get a divorce in the United States, where the laws were considerably more liberal, American divorces only provided a limited degree of social respectability, as they had no legal standing in Canada. The courts in Canada made things even more difficult for the unhappily married. Adultery was the primary grounds for divorce during most of the Confederation era, and the courts frequently imposed a punitive element to any judgment, stipulating that the offending party could not remarry while their original spouse was alive.

In terms of the era’s views on gender parity, it wasn’t just a matter of attitude: women in the Confederation era were legally inferior to men. Women of the era had a long way to go. The BNA Act of 1867 used the word “persons” to refer to more than one person, and “he” when referring to one person. This wording was clarified in 1876, when a British judge ruled that “Women are persons in matters of pains and penalties, but are not persons in matters of rights and privileges.”1

A party of women enjoying a good laugh as they travel on the forward deck of a Lake Ontario steamboat, late 1860s.

In virtually every aspect of their lives, women were repressed. An intrinsic part of that repressive culture was the period’s legendarily puritanical and bizarre attitude to sex. An argument can be made that gender repression and Victorian neurotic sexual repression were two sides of the same coin, that Victorian anxieties about the future were in part bred in the changing economic and social structures of a newly industrialized society. They were obsessive and unsuccessful attempts to exert control over a society changing in ways its leaders neither understood nor wanted. While there may be some truth to this, it’s also likely that gender roles were evolving logically and inevitably as society industrialized and education levels rose, that the era’s sexual concerns were rooted in ignorance of biology and human nature, as well as a poorly articulated desire to prevent women from achieving the same status as males, thereby preserving a manageable semblance of what the old society was like. In Canada, all of these elements were present in the Confederation decades. Canada displayed the same kinds of behaviours with regard to sex and the women’s movement that surfaced in Britain and America.

Most men in the era were resistant to any change in the roles of the sexes and viewed the very notion of women’s rights as politically preposterous; however, not all held that view. John A. Macdonald was the world’s first democratic leader to attempt to give women the vote. In 1885, he introduced legislation on the subject, but it floundered in the House of Commons. Macdonald put the issue aside, but predicted that one day Canadian womanhood would “completely establish her equality as a human being and as a member of society with man.”2 He was decades ahead of his time, however, and his notions of a society where women would be equal was deemed so absurd it did not merit further serious legislative discussion for another decade. Instead, women’s issues were temporarily subsumed by the labour and temperance movements and religious organizations.

Although women’s rights movements were sneered at and generally treated with contempt, the women’s movement grew slowly but steadily. Activists in the movement had to be cautious and secretive in their activities. For example, in Toronto, the women’s rights movement had to operate under the innocuous title of “The Toronto Women’s Literary Society.”3 It was a kind of camouflage that allowed women to leave home for the evening to discuss the issues of advancing women’s rights.

There were, however, some gains made during the period and, although they were tentative, they were important. In several constituencies, women were granted property rights separate from their husbands. For example, the Public Lands of the Dominion Statute allowed homestead land to be given to a woman only if she was unmarried and had dependents under the age of majority. In Ontario, a law was passed in 1882 allowing unmarried women who held property to vote in municipal elections.

Very few were admitted to university programs, but during the later years of the period that began to change. Grace Anne Lockhart was the first woman to receive a baccalaureate in all of the British Empire when she graduated from New Brunswick’s Mount Allison College in 1875. In the same year, Jennie Trout was licensed in Toronto to practise medicine, but only after getting her medical degree from a woman’s college in Pennsylvania.

Despite these exceptions, women were raised to believe that their place was in the home as a wife and mother. This expectation was true at all levels and in all ethnic groups. Only a small minority of bold and independent thinkers challenged the notion, and these were, for the most part, women whose circumstances gave them the opportunity to see beyond the confines of their situation.

In rural Canada, in particular, the role of a farmer’s wife had evolved into a highly restrictive but economically indispensable function in society. Women on farms were raised and trained in the not inconsiderable tasks of running and managing a rural household. From dawn until dark, their lives involved an eclectic variety of diverse skills, such as cooking, animal husbandry, preserving foodstuffs, baking, cheese making, beekeeping, care of the sick and elderly, candle making, raising children, spinning wool, sewing clothing, butchering animals, gardening, cleaning, washing, and preparing scores of items that we buy today as manufactured goods. Like their husbands, who managed the never-ending list of chores outside the house, Confederation-era farm women were busy people.

Because Confederation-era farm women lived such frantically demanding lives, in hindsight it is easy to see that the women’s movement was primarily an urban phenomenon. All the advances in women’s rights during the period were made by women who lived in towns and cities. This might be explained, in part, because farm life was more of an equal partnership than urban life. But as important as the advances in this era were, they were limited, and the suffragette movement remained in its infancy.

One striking difference between rural Confederation-era families and modern ones was care of the elderly. Given the mortality statistics — women routinely outlived their husbands, often by considerable margins, it was quite normal for widows to move into the homes of their children. There was really no alternative to this arrangement. Life on a Canadian farm was a rigorous existence, where simple tasks, such as keeping the house warm in winter, entailed cutting wood and feeding a stove. They were chores that took energy and agility. In these circumstances, a single aging person on an isolated farm was usually unable to cope. In the event of dementia, there was not much that a family could do; children would normally be tasked with caring for the infirm, but often that task was too great for them. Elderly patients who became a hazard to themselves and their families and could not remain with the family were sometimes committed to poor houses or asylums in nearby towns. Such instances were exceptional, and occurred only if the option was available, which was not always the case. Those unfortunates who were sent to public institutions would end their days in harsh and appalling environments. Deprived of medical help and the affection of a family, they rarely survived long in their new surroundings.

Although the nuclear family was the predominant and most important social institution in the era, households often contained more than just family members. As the size of farms grew, Confederation-era farmers often hired seasonal help. In the early years, these hired hands more often than not lived with the family, or on larger farms, such as on the Prairies at harvest time. They often lived in a bunk house next to the farm house, and many of them ate with the farmer’s family.

As farms grew more prosperous, as most did throughout the Confederation decades, farm families had the means to take on additional help. Throughout the period it was not uncommon for them to have servants. In the early years of the century, 20 percent of rural servants were males, but by the 1840s, they were almost all young women. Domestic service was the most common employment for women in Canada, and we know from the 1891 census that Canada had over eighty-thousand such women working in private homes.4

Most farmers and their families regarded themselves as being ruggedly practical people, belonging to a large, relatively equal and independent society. It wasn’t just nobility of spirit that underlay these attitudes. There was a practical basis for this impartiality; manpower was scarce, and people and talent had to be distributed how and when they found it. While they were not entirely innocent of class prejudices, most Canadian farmers regarded notions of restrictive class structures as belonging to the old country and urban status seekers. For them, there was little profit to be had devoting time or energy to developing a convoluted class system.5

On Canada’s farms, young women employed as domestic help were not treated as social inferiors. In fact, from the statistical analyses of the period, we know that rural domestic servants were socially mobile and had a high turnover rate. By the early twentieth century, the field of domestic service in rural Canada had virtually ceased to exist — almost certainly because these women married into the local communities, or moved into the cities and towns as industrial work became available. Catharine Parr Traill painted a vivid picture of this mobility:

What an inducement to young girls to emigrate is this! good wages, in a healthy and improving country; and what is better, in one where idleness and immorality are not the characteristics of the inhabitants: where steady industry is sure to be rewarded by marriage with young men who are able to place their wives in a very different station from that of servitude. How many young women who were formerly servants in my house, are now farmers’ wives, going to church or the market towns with their own sleighs or light wagons, and in point of dress, better clothed than myself.6

Home children sent from Britain’s poor houses also became a source of assistance on Confederation-era farms, and in many families these children were freely adopted and treated as new family members. On others, they were exploited and dealt with cruelly. Although the evidence for this latter category is entirely anecdotal, it is likely the number of children who were treated harshly was small.

What was beyond doubt regarding the employment and treatment of children was the prevalence of child labour during the Confederation era. Children did not have effective legal protection from being exploited as a source of labour in Canada until well into the twentieth century. Throughout the Confederation decades, working children were an important part of family life. In most towns and cities, the salaries made by children were essential for the economic survival of working-class families. In the same manner, Canadian farms could not get by without large numbers of children working.

Confederation-era Canadians regarded childhood much differently than we do today. For many, childhood was a much more abbreviated period of one’s life. There was no conception of, or desire to understand, a child’s mental or physical developmental periods. Children were given adult responsibilities years before they reached puberty. In the early years of the era, it was normal to have children as young as seven working as machine operators in textile mills in Montreal, as bellows operators in Nova Scotia’s coal mines, as house and stable cleaners or stock boys in Toronto, or doing scores of tasks on farms across the country.

In 1861 Montreal, one-third of working-class boys under the age of fourteen were employed full-time. It probably was not much different in other cities. Nor did the situation improve throughout the Confederation decades. From the 1870s to the 1890s, the percentage of child labourers rose steadily.7 In 1884 in Ontario, the Factories Act was introduced, which established the working age as twelve years old for boys and fourteen years old for girls. For both groups, it restricted the hours of work to ten hours a day, or sixty hours a week — with clauses nullifying the Act in the event of undefined “breakdowns” or “exigencies of the trade.” It was better than nothing, but not much. There were no enforcement mechanisms in the bill and verification procedures were never defined or implemented. The ages cited in the Factory Act are worth noting. Twelve-year-old boys and fourteen-year-old girls were, for the purposes of full employment, considered adults. It wasn’t unusual for the time. The concept of adolescence did not exist until the early 1900s, when American psychologists began to conduct a scientific analysis of the transition to adulthood.

As a practice, most Canadians regarded child labour as being essential to a healthy economy. This kind of thinking was so accepted that when several bills to prohibit child labour were introduced in Parliament in the 1870s and early 1880s, they were all soundly defeated, or simply allowed to languish on the order paper without ever being debated.

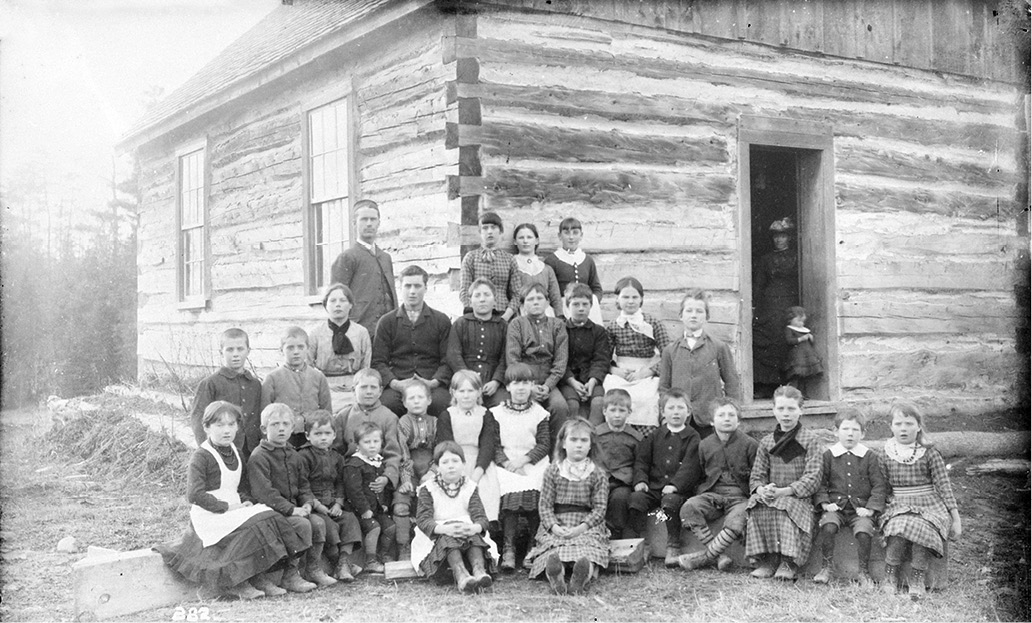

In New Brunswick, a typical rural schoolhouse of the Confederation decades with teacher and students. Although the school year was short, free schooling meant that overall literacy levels in Canada were high compared to the rest of the world.

Educators in the nation’s school system were not opposed to child labour. Schooling was intentionally designed to give working-class children and farm children access to free, compulsory education; but, along with this, the school year was designed specifically to enable children to spend most of the year in full employment. Ontario was a good example. The Ontario School Act of 1879 was written so that each municipality was obliged to provide children between the ages of seven and twelve only four months of schooling each year.8 The remaining eight months were not reserved for holidays, but to allow children the chance to do farm and factory work.

The education system was also designed to ensure that women received a minimal level of instruction. With the rise of compulsory education in Canada in the early 1870s, the number of girls in the system almost equalled the number of boys.9 However, the prevalent social expectations were such that girls were encouraged to leave school by no later than fourteen. Beyond this, education for girls was usually only provided at private colleges, and for those who could afford it. The colleges generally made no attempt to meet any clearly defined academic standards; instead, they trained middle-class students in the social graces and prepared a growing number to become school teachers. Teaching was one of the few professions open to women. Because the period mindset was that women had special “nurturing” aptitudes, women were accepted as teachers; and, perhaps more importantly, for governments anxious to keep rising education costs in check, they could be hired at much lower wages than men.

Aboriginal schooling in the period reflected the indifferent and brutally offhand government approach to the treatment of First Nations. In the early colonial years of the Confederation decades, a number of voluntary “manual schools” were established for aboriginal children, largely with the intent of assimilating them by teaching them to become farmers. For reasons already discussed, these efforts failed right across the country. With the Indian Act, the federal government assumed responsibility for the education of all Status Indians. Manual schools were followed by a further feeble attempt to create local day schools, which were run almost entirely by missionaries. There were serious problems with these schools. They were characterized by underfunding, insensitivity to languages of instruction, cultural disdain, inappropriate curriculum, inadequate teaching, and, not surprisingly, poor attendance.

In 1879, Canada, in imitation of a U.S. model, adopted a system of residential schools. To save money, wherever possible existing mission schools were used. Attendance eventually became compulsory. To achieve this, primary-school-age aboriginal children were forcibly wrenched from their families and sent off for years to be schooled in either English or French. While some schools were reasonably well-run, many others were not. Many residential schools had virtually no supervision, and many of them experienced all the problems of the previous system, but they were run with an institutional harshness and a malignance that is now difficult to comprehend.

A school for aboriginal children, northern Manitoba, early 1880s.

In virtually all schools, small children were torn from their families and moved hundreds of miles away. In the worst schools, small children were physically punished for speaking their own language; their ration scale in many cases was criminally inadequate; they were routinely housed in inadequately heated barrack-style accommodation; and many were subject to physical and sexual abuse from their teachers and older children. Over three thousand children died from tuberculosis, and the standard of education was such that few progressed beyond the most basic levels. When they completed their schooling, they were inadequately prepared to compete for jobs in the larger economy.

The system lasted in one form or another for almost a century. Starting in the Confederation decades, several generations of aboriginal children were kept out of sight, living unpublicized for decades in horrendous conditions, with widespread disease, and a mortality rate similar to a low-intensity war. Residential schools inflicted massive psychological damage on generations of vulnerable children. It is an ugly part of our history that the rest of Canada is only gradually beginning to accept.

While most Victorian Canadians had an education system that was inferior in virtually every way to today’s, those who lived in rural areas had a diet that was substantially superior. Confederation-era Canadians suffered from diseases that have been largely eradicated; their water was often unfit to drink; they had no antibiotics; their occupational safety standards were far below current ones; and their overall mortality rate was higher, but for the majority of the population, especially those who lived in the rural areas, their basic diet was healthier. They rarely ate processed food of any sort, and their consumption of sugar and salt (despite preserving their meat in brine) was well below ours. Victorian Canadians generally ate fresh food. Confederation-era diets were high in regionally grown fruits, locally raised vegetables, and whole grains. And while they had nothing like the variety of choice to be found in a Canadian supermarket today, the food they did eat was basic, nutritious, and free from pesticides and drugs.

Processed foods would start to be introduced in quantity to the Canadian diet near the turn of the century, with the introduction of sugar-sweetened condensed milk and canned fruits swimming in syrup. However, for Canadians of the Confederation era, their diet consisted in the main of numerous kinds of root vegetables, legumes, seasonal vegetables, corn, whole grain breads, apples, pears, plums, pumpkins, berries, pork, beef, poultry, and fish.

Given the physically intensive nature of their work and daily lives, most rural Canadians and urban labourers of the period consumed far more calories than we do.10 Despite that, as a society, they did not experience the problems with obesity that we now have.

There was never an issue with the amount of food being produced in the country, but there were problems associated with the diets of many in the Confederation era. Social and economic inequities meant that elements of society periodically went hungry and were malnourished. There were also other dietary problems that cut across all class and regional lines. For example, we know that alcohol consumption was very high and caused widespread health, economic, and social problems. Our understanding as to the exact scale of this problem is speculative, as records are almost all anecdotal, but we are certain that high alcohol consumption had a harmful effect on society. We know from production and sales statistics that drinking habits in Canada changed during the Confederation decades. In the early years of the century, cider and beer, which were often home brewed, were the most common drinks; but starting in the middle of the century, spirit consumption rose swiftly. Domestic whisky and Jamaican rum sales increased on a year-over-year basis.

An Ontario farmer harvests a substantial turnip crop, 1870s. The introduction of fertilizers, crop rotation, and factory-made agricultural machinery in the Confederation era increased yields and meant that food was plentiful.

Not surprisingly, at the same time, temperance movements gained traction in every part of Canada.11 The temperance movement had its initial roots in immigrant British and American evangelical Baptists and Methodists, but the cause also had strong support from urban middle-class businessmen, who wanted sober, reliable employees. Although the Canada Temperance Act in 1878 granted regions the power to implement prohibition at local levels, national prohibition was never actually implemented during the Confederation decades. However, failure to implement national prohibition during the Confederation decades did not deter the federal government from imposing prohibition on First Nations. From the time of the Royal Proclamation, Canada had created a series of laws outlawing the sale of liquor to First Nations, laws which eventually were repeated in the Indian Act of 1876 and were not substantially changed to give local band councils the authority to decide for themselves how to deal with the issue until 1985.12 New Brunswickers, on the other hand, voted in favour of prohibition in 1852, but the law was only implemented within certain counties, and it had several loopholes that allowed anyone who wanted to drink to get around the restriction. Similarly, by 1850, over half of Quebec’s francophones, influenced by a group of charismatic priests, had taken temperance pledges, but the provincial legislators never took any action to implement prohibition.13 The temperance movement exerted a strong undercurrent in nineteenth-century Canada, but actual prohibition only surfaced regionally for short periods in the early twentieth century.

Funerals and the attitudes toward death during the Confederation era were markedly different than modern sensibilities. One of the most striking differences was that fewer people died in hospitals. The most common causes of death throughout the era were from infectious diseases. If you were terminally ill and were in a hospital, you would usually be sent home to die amongst family and friends. Hospitals were reserved for those likely to recover.

The result of this was that death was something much closer, more immediate, and more familiar to Confederation-era Canadians. They experienced it first-hand, in their bedrooms and in their parlours. Seriously ill people who were dying at home would sometimes have their bed set up in the parlour. Downstairs was usually closer to a stove and therefore warmer during the cold months, and the family could more readily attend to a patient. Often, the family and close friends would remain at the patient’s bedside day and night, waiting for death, anxious to hear their loved one’s last words.

After death, the dead were often kept within the home. Family members washed and dressed the body. The practice of embalming bodies was rare during the Confederation period. Embalming has its origins with the ancient Egyptians, but it did not become popular in North America until after Abraham Lincoln’s death, when his body was preserved for an elaborate state funeral. In Canada, the practice did not begin to become popular until the early 1900s.

A local carpenter would usually make and deliver a simple coffin to the bereaved family. The coffin would be taken to a church in a wagon, often by horses draped in black cloth and decorated with black ostrich feathers. Later in the period, in towns and cities, livery stables would rent the use of a black, glass-sided hearse. Funeral parlours, which evolved into funeral homes in the twentieth century, did not begin to come into vogue in Canada until late in the 1880s. It wasn’t until the 1920s that customs changed and care of the dead was routinely outsourced to undertakers. As funerals became more elaborate and removed from the home, and death became less familiar, the undertaker evolved into a funeral director, who handled all aspects of a funeral, except the actual religious ceremonies. Funerals were invariably held in the mornings, and in the more genteel classes, personal invitations were sent out requesting attendance. Mourners would dress in black and accompany the coffin from the church to the gravesite. In winter, coffins would be stored in a stone or brick mausoleum until the ground thawed sufficiently to allow internment to take place. Even for the poorest in Canada, proper burial came with a coffin, a church service, a plot, a headstone, and a decent wake. To be buried with anything less was considered a disgrace, and even the poorest Canadians scrimped and saved. The poorest put money aside in burial clubs and friendly societies to ensure that in death they avoided shame and were given a proper “send off.”14

Once a death occurred, families would open their windows, close the blinds and drapes, and cover all mirrors. This tradition had its origins in superstitions related to the passage of spirits and bad luck, but in the Confederation era the practice grew into a traditional custom. Frequently, as a sign of respect, clocks would be stopped at the hour of death. Front doors would be draped with cloth to warn others that someone had died within. Black cloth was used to signify the death of an adult and white cloth to mark the death of an infant or child.

Confederation-era Canadians had very specific rules regarding mourning clothes. It was considered to be bad manners to wear any colourful clothing to a funeral, and the bereaved were expected to wear mourning clothes, usually black, for a year or more while they were in “deep mourning.” For at least another six months, while they were in “half mourning,” they would wear some conspicuous piece of black clothing to indicate that they were still observing a period of grief.

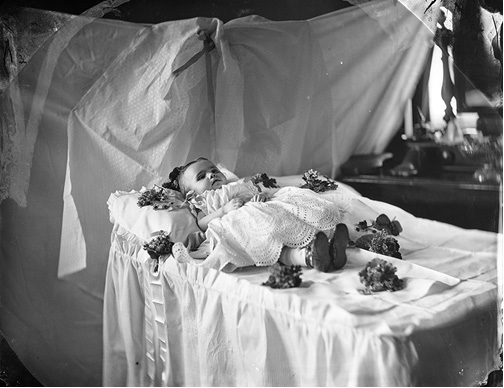

An infant corpse photographed at her wake, Montreal, 1869.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable practices that developed during the period was photographing the dead. If the family did not have a photograph of the deceased, which was most often a child who had died suddenly, a photographer would take a picture of the dressed corpse. Sometimes the corpse was braced up in a sitting position surrounded by his or her relatives, and not infrequently the eyes were propped open to feign life, but most often the departed would be resting in a natural sleeping position. To twenty-first-century sensibilities, this seems macabre, but for people who were accustomed to death and handling corpses, they obviously thought the practice was appropriate, as it provided a grieving family some means of remembering a loved one.