Chapter Seventeen

Institutional Life

Government institutions during the Confederation era were relatively austere by present standards. The BNA Act gave the federal government responsibility for the regulation of most matters of trade and commerce, criminal law, and for those issues where the legal or practical jurisdiction spanned more than one province. In turn, the provinces received control of “generally all matters of a merely local or private nature in the Province.”1

From the outset, Canada and the provinces had substantial and well-established bureaucracies to run their organizations.* In the 1860s, Canada carefully followed the very recent British example of developing a civil service that was proficient, professional, and selected for their jobs on the basis of competence via an impartial selection process.2 The men who established Canada’s public service were on the whole successful. Canada was fortunate in having a lean and efficient public service with traditions of competence and professional integrity.

Over the years, the administrative, regulatory, and financial arms of government and civil society have assumed greater responsibilities and grown much larger. We are accustomed to thinking of national bureaucracies as being faceless and colourless, and while this may be true for some, the era’s hospitals, prisons, charitable institutions, and military provide a fascinating and revealing glimpse of the era’s character.

Canadian hospitals and medical care evolved substantially during the Confederation decades. In the 1840s, most acute and chronic medical care was carried out in the home. There were few hospitals, and the ones that existed were small and located only in larger towns and cities. There was also, up until the very early 1860s, a social stigma associated with being admitted to hospital. Those who could afford it hired doctors to look after them at home. Hospitals were seen as a kind of charity, a place for treatment of the needy. Being admitted to a hospital meant accepting a loss of control over one’s life by allowing your treatment to be directed entirely by strangers.

Fear of hospitals was not entirely unfounded. During the Confederation era there was little understanding of germ theory. Although in the late 1850s, Pasteur had discovered the nature of germs and their relation to disease, his ideas took a long time before they were accepted by the medical community. By the 1880s, many doctors still believed in “miasma,” a theory of infections based on foul airs. As a result, hospitals throughout the Confederation era had high rates of post-operative infections. Operations themselves were also rudimentary procedures. Because of the risk of infection, amputations were common and wounds and bleeding were cauterized with hot irons or boiling oil. Ether’s use as an anesthetic began in Canada in the late 1840s and was eventually replaced by chloroform, both of which had serious and often life-threatening after-effects.**

Another reason people tended to avoid hospitals was in part due to the roaring trade in quack medicines. Dubious remedies abounded for practically every ailment. Liniments, pills, oils, tonics, and pastes were sold to treat every known illness. There was no effective legal regulation of medicines in Canada until the introduction of the Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act in 1909. Before then, the ill, the gullible and the desperate bought fraudulent remedies in large quantities. Pharmacies existed, and they were regulated as early as 1867, but during the period, the pharmacist’s role was primarily making and preparing drugs rather than regulating their sale and distribution.

One home medicine that was readily available without prescription was laudanum, sometimes called tincture of opium. A morphine derivative, its use was widespread throughout the Confederation era. In the absence of other medications, such as aspirin, people self-medicated with laudanum for every conceivable ailment. However, the most common conditions the drug was used for were asthma, diarrhea, headache, toothache, and arthritis. As a result, people regularly became addicted to laudanum, yet surprisingly, after the late eighteenth century, there was little evidence of laudanum’s use as a recreational drug. In the same tradition of home-based remedies, cocaine eventually became popular as a medicinal product in a number of treatments, but its use did not become commonplace in Canada until after the Confederation era.

Throughout the Confederation decades, dental work in Canada was rudimentary. There were few qualified dentists in the country, and for most of the period, those who were qualified were trained via a four- or six-month apprenticeship. The resultant skill levels from this haphazard form of qualification varied from amateurish to dangerous. Many dental apprentices went on to became itinerant dentists who visited remote communities on a periodic basis.

Because there were so few dentists, most dental work during the period was performed by local physicians, who also had minimal training in dentistry. As a result, dental work throughout the period was often appallingly crude. Pulling teeth was the most common treatment for virtually all ailments. It was a painful and unsophisticated procedure, which more often than not entailed infection and damage to the patient’s jaw bone. Anaesthetics were rarely used. Instead, the common practice was to “freeze” the affected area by holding ice against it prior to extracting the tooth. This only provided slight relief from pain. Very wealthy Canadians could get porcelain teeth made in Toronto and Montreal, but most often, the more affluent had their false teeth and rudimentary fillings made from gold and silver. Things began to improve near the end of the period. The first dental college was established in Toronto in 1875, but it would not be until well into the twentieth century that there were sufficient numbers of dentists to meet the country’s needs.

It would be wrong to think of the Confederation period as being forty years of home-based medical incompetence. Although the era did not have anything like the modern emphasis on research and development, Canada did have its own teaching hospitals. The first true Canadian teaching hospital was the Montreal General Hospital, which started training doctors in the late 1820s. Canadian teaching hospitals were not just imitations of European or American institutions. They were innovative in their medical teaching practices. For example, Montreal General pioneered the art of bedside teaching, while Dartmouth’s Nova Scotia Hospital was one of the first hospitals anywhere to teach and develop the field of occupational therapy.

Canada was much slower in training nurses. The first nursing schools did not open until 1881 at Toronto’s General Hospital. Five years later, Montreal’s Women’s Hospital graduated its first nursing class. Educating nurses in the medical arts was a radical departure from the past. Few nurses, both lay or religious, had any medical training before the 1880s. Their primary functions were to watch over their patients and keep them clean. In Canada’s lay hospitals there was also a distinct social hierarchy amongst the nursing staff, as middle-class women were hired in a supervisory role to monitor both the nursing staff and the maids who did the laundry and cleaning.

General hospitals were originally secular hospitals, as opposed to hospitals run by religious orders, most of which were run by nuns who had taken vows of poverty. Despite this, throughout the Confederation era, all hospitals ran on a precarious basis. They operated on public donations, government grants, and whatever they could get by way of patient fees. Often there wasn’t enough money. In 1867 for example, the Toronto General hospital had to close for a year due to a lack of funding.

Mental illness was never well understood by the medical community during the Confederation era. However, a small number of doctors realized that the mentally ill could be treated better than they were. The early nineteenth century was a time when those suffering from mental illness were simply housed in jails and prisons. Although this practice wasn’t entirely eliminated in the period, there was a movement to try to understand mental illness and deal with it more humanely. Unfortunately, the approach that was adopted was to treat the problem as a moral failing, and unless the condition healed on its own, few psychiatric patients of the period ever improved.3

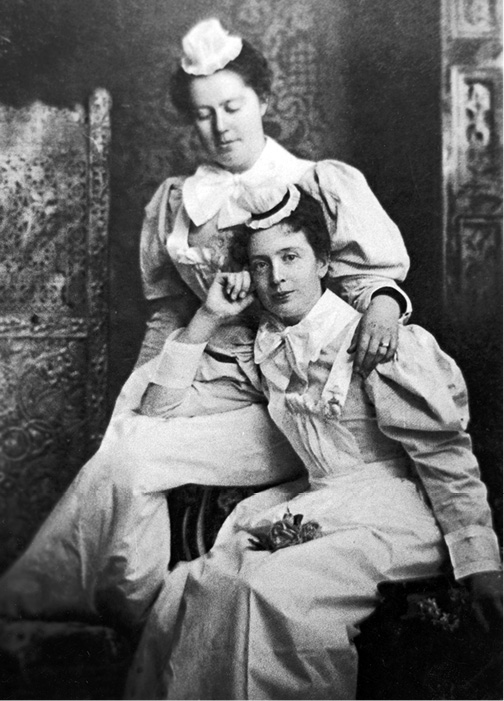

Two of the first of Canada’s professionally trained nurses, Ontario, late nineteenth century.

By 1857, “lunatic asylums” had been established in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario. The asylums of the Confederation era were in reality little better than prisons. Lunatic asylums served as warehouses for the mentally ill: the food was appalling, communicable diseases were rife, individual care was haphazard and, more often than not, non-existent. The provincial asylums were regarded as institutions of last resort for those with prolonged and untreatable illnesses, or who could no longer be cared for by their families. For those mentally ill individuals who were arrested for vagrancy or more serious crimes, judges and juries could acquit a defendant on grounds of insanity. Special accommodation in prisons was made for the criminally insane, but in practice what the inmates received was little more than solitary confinement in a nine foot by five foot cell.4

A revealing indication of the official perspective on asylums and prisons can be seen in how they were grouped for government administrative purposes. Throughout the 1850s and ’60s, the oversight body in Ontario consisted of a “Board of Inspectors of Prisons, Asylums, and Public Charities.”5 It was consistent with a world view that made little practical distinction between criminality, poverty, mental disability, unemployment, and alcoholism.

In line with this way of thinking, the state of prisons and jails in the Confederation era revealed much about the character of the society. Prior to the Confederation era, judicial punishment included a range of sentences, such as: the death penalty, flogging, mutilation, branding, and exile. John Howard, an influential British advocate of penal reform in the late eighteenth century, lobbied for a number of changes. He believed that the judicial system should focus on reform and deterrence rather than vengeance. Howard believed that criminality was caused by a lack of properly instilled moral values and structure in one’s life. He urged such things as separating prisoners in cells in accordance with the degree of their crimes, providing intensive religious training, employing convicts at hard labour, enforcing prohibitions against the sale of liquor to prisoners, and providing prisoners with adequate clothing.6 Howard’s ideas gained currency in North America, and eventually found their way into the Canadian penal system via American examples. One of the results was the establishment of the Kingston Penitentiary in 1835.

The Kingston Penitentiary was Canada’s largest non-military building of its time. An imposing structure, it housed 880 prisoners in cells, with each original cell measuring six feet by two feet. Prisoners were kept in absolute silence, except for when they were allowed to speak in the course of their duties. Prisoners worked on a central shop floor manufacturing leather goods and woodwork, cutting stone, and metalsmithing on a forge. Women performed compulsory needlework. Their finished goods were sold by bid on commercial markets.

Few Canadians of the period showed any interest in prisons, and this in turn resulted in little supervision of their management. Prisoners in penitentiaries were required to live in what was called partial isolation. They were forbidden to speak to one another in order to better reflect upon their wrongdoings. Food was execrable. Floggings could be handed out on the recommendation of a guard, and chaining prisoners in their cells was common. Troublesome prisoners were placed for days on end into the “box,” a wooden, coffin-like case with a small breathing hole. Local jails were little better. In 1861, an observer of the Ottawa Jail found that the cells were damp and dingy, women, children and men were routinely held in the same rooms, and toilets were dark, unwholesome, and “overflowing with abomination.”7

Charitable institutions in the Confederation era showed a similar improvement from the period that preceded them. For example, as we’ve seen, the homeless and the destitute were popularly and officially divided into classes of the deserving and undeserving poor. Despite this categorization, the poor were generally regarded with suspicion, as there was a popular, deep-rooted notion that giving the poor charity would encourage “idleness.”

New Brunswick provides a good example as to how attitudes to charity changed. In the early years of the nineteenth century, the city of Saint John had scores of paupers. It was a port, and people often arrived sick, orphaned, or otherwise incapable of working. The colony had, in the eighteenth century, instituted laws that tasked parishes with responsibility for the poor. These early laws were based upon English precedent — a precedent that was established in the Elizabethan era. Because the poor tended to congregate in the urban areas, the residents of Saint John felt that the laws placed an undue burden on them. To help defray their expenses, they held auctions and gave the lowest bidders money to house the poor as they best saw fit. When that proved to be inadequate, a tax was levied on dog owners to help pay for the upkeep of paupers. The dog tax proved to be insufficient, and the funding source was broadened to include fines levied on the owners of stray horses and hogs. Stray horses and hogs were a serious problem. They caused considerable damage to crops and gardens, and the new law was designed to fix two problems. The system of auctioning off care of the poor was subject to horrific abuse, and the revenues raised from dogs, horses, and hogs proved to be insufficient. The colony eventually established almshouses and poorhouses. A poorhouse was a punitive workhouse, and an almshouse was a much less demanding and more charitable shelter.8

Poorhouses were a feature of Canadian cities well into the early twentieth century. Fortunately, their quality improved steadily, but during the Confederation era there was considerable variation in the quality of their services. Many poorhouses provided wretched accommodation and treated the “inmates” no differently than criminals. Others were supported by the charity of church parishes, and provided a warm, dry, and comforting place to live. Nonetheless, poorhouses were few in number and space was limited. Consequently, it was not uncommon to commit those with significant intellectual impairments to local jails. It was a cruel practice, as many were shackled in basement cells or housed alongside violent criminals. As the jails became crowded, the mentally challenged were often declared as “dangerous lunatics” and admitted as permanent wards of the state to the provincial lunatic asylum.9

Two enthusiastic militia soldiers from Toronto demonstrate the correct drill for attacking parlour furniture, Toronto, 1870.

While treatment of the poor and mentally challenged has changed over the years, Canadian attitudes on national defence and the military have shown remarkable consistency. Throughout the Confederation era, the only major security threat to Canada came from the United States. Up to that time, Americans had threatened Canada with some regularity. In 1775, Benedict Arnold led an unsuccessful attempt to seize Quebec in one of the opening moves of the American Revolutionary War. Thirty-seven years later, in the War of 1812, as a result of British attempts to restrict U.S. trade and America’s desire to expand its territory, U.S. troops mounted several incursions into Canada. A half century after that, Fenians, American Irish veterans of the Civil War, launched several raids into Canada in an attempt to force Britain out of Ireland. Confederation-era Canadians understood that there was a real military threat, and that it had reappeared with a degree of consistency. Nonetheless, Canadians were reluctant to invest in their military forces.

As relations between the United Kingdom and America soured during the Civil War, the British were anxious to see Canada bear some of the cost for its own defence. Sir John A. Macdonald agreed, and introduced a bill to create a trained, equipped, and paid militia of 50,000 men, some of whom could be chosen by a form of conscription. Macdonald’s bill was defeated, his government fell, and the ensuing government passed a bill authorizing a militia force of 10,000 inadequately equipped, unpaid volunteers who were to receive a maximum of twelve days training each year. Fortunately, when the Fenians attacked several years later, they did not prove to be a determined enemy. The threat disappeared after a few minor battles, and the American government intervened to prevent further provocations. Despite an enthusiastic response by the militia, the brief conflict showed serious inadequacies in equipment, training, and organization — issues that were well understood beforehand, but assiduously ignored.

As relations with the Americans improved, in 1871, with the exception of small garrisons in Halifax and Esquimalt, the British withdrew all of their troops from North America. To act as a training nucleus for the militia, in the 1870s Canada created a handful of miniscule, undermanned, and underfunded regular army units. The militia provided the troops for the bloodless Red River expedition in 1870. But for the remainder of the period, Canada’s army remained untrained, ill equipped, and wracked by patronage.10 The military’s experience during the Confederation era typified Canada’s paradoxical and enduring attitudes to defence preparedness: the country relied on more powerful allies for its defence, while maintaining enthusiastic, but the smallest possible peace time forces.

Canada’s monetary system and policies have undergone a radical transformation over the years. Long before Confederation, the Canadian monetary system was a jumble of currencies. During the early years of the Confederation decades, if a farmer went to the local general store he would not necessarily have conducted his transactions using British pounds. The pound sterling was not the primary currency. American dollars, British pounds, locally produced bank notes, and bank notes from the Atlantic colonies were all in use, with each of the British North American colonies deciding for itself the value, or “rating,” of the various currencies. In 1858, to simplify things, and in a move indicative of the prevailing international trade links, the government of Canada passed a law that all government financial reckonings be tracked in dollars. During that same year, the government issued coins in Canadian denominations.

Prior to Confederation, Canadian dollars were issued and secured by several different regional banks. It was a simple arrangement. There was no central bank; banks had to secure any bills they issued, and the Canadian dollar was generally assumed to be equal to an American dollar. Although several smaller banks failed in the 1850s, causing a brief period of financial uncertainty for Canadian dollars, the system worked reasonably well. After Confederation, the government assumed jurisdiction over currency and banking. In April 1871, with the passage of the Uniform Currency Act, the Canadian government finally replaced all colonial currencies with Canadian dollars.11 Canada did not create a central bank until 1935, and chartered banks were allowed to continue issuing their own bank notes until 1944.

* By way of comparison, in terms of the public service’s relative size, complexity, importance, and breadth of responsibility, while Canada’s population is now ten times larger than it was at the time of Confederation, the national public service is 271 times larger.

** One of the first people to use chloroform as an anaesthetic during the period was Abraham Lincoln, who in 1862 insisted it be used on him during a tooth extraction.