Chapter Eighteen

Education, Media, and the Popular Arts

As a small frontier nation, Canada did not make a large contribution to the arts during the Confederation era. Canadians were, in comparison to other nations of the period, a very literate population and they valued culture, but it was a small market from which to support any kind of sustained and viable arts community. On the other hand, basic Canadian educational standards were relatively high; and, although no comprehensive literacy tests were conducted in Canada until well into the twentieth century, there is evidence that a substantial percentage of the adult population could read and write. Those who graduated from elementary school generally displayed in their writing a firm grasp of grammar, a broad vocabulary, and a sense of logic and clarity. Contemporary letters and documents indicate a society that was functionally literate, but, in comparison to modern tastes, was somewhat florid in its written expression.1

Letter writing was considered to be an art form, and the ability to write an informative and entertaining letter was highly valued. Like so much else during the period, there was a strict etiquette surrounding letter writing. Next to an actual conversation, letter writing was the most important and predominant form of communication. There were numerous references available on the subject of letter writing, detailing everything from correct forms of address to the appropriate timing and frequency of letters to individuals. The quality of a letter was regarded, not unreasonably, as an indicator of the writer’s intellect, social standing and sincerity. As a result, painstaking attention was given to their drafting. In our own time, where abbreviating text messages to their simplest possible comprehensible configuration is seen almost as an art form, the letters of the Confederation decades seem to be exaggerated and flamboyant extravagances.

Letter-writing styles were in part a product of the period’s educational system. As we’ve seen, the compulsory period for Canadian education was short, but it was also disciplined and rigorously focused on classical models. For its time, it was one of the best universal education systems in the world. Egerton Ryerson, who was the driving force behind much of English Canada’s attitudes to education, was a zealous believer in classical pedagogy. The emphasis in schools, both in English- and French-speaking Canada, was on personal discipline, rote learning, repetitive drills, handwriting skills, arithmetical problem solving, and memorization of lengthy passages from the classics and the Bible. In the higher grades, Latin and Greek were deemed to be an essential part of a rounded education.2 Although children were divided into grades, most of the schools were rural and had only one teacher instructing everyone. Often in such cases, older students served as “monitors” who oversaw and tutored the younger students. Throughout the period, vocational education was regarded largely as a responsibility of private industry.

Discipline in school was more than just a means to an end. It was considered to be a laudable academic goal in itself, one which was inextricably tied to academic achievement and social progress. Based upon studies in the United States, men like Ryerson believed that literacy was a key factor in reducing the crime rate. It was a belief that led Canadian educators to favour free, high-quality public education that stressed classroom discipline. Nineteenth-century Canadian notions of academic discipline encompassed not only adherence to rules, but discipline was also viewed as a means of developing the qualities of determination and intellectual tenacity in the general population. Perseverance, steadfastness, and high moral character were thought to be inculcated by rigorous instruction in the three Rs and unremitting exposure to classical teachings. It was also a time when schools were viewed as an opportune means to indoctrinate patriotic and civic values. After 1867, civic education in most Canadian schools stressed loyalty on regional, national, and imperial levels. Love of country and Empire as well as Christian values were stressed in literature, music, history, and geography lessons. There is little evidence of any serious opposition to this instruction, and new immigrants from America as well as mainland Europe showed every indication of being eager to adopt the civic values of their new country.

Although Canadian schools had many similarities to British and American educational programs, curriculums were largely determined by Canadians, and the belief in mass education meant that schooling was for its time generally more accessible to the entire population than it was elsewhere in the English-speaking world.3

Newspapers and magazines were popular during the Confederation period, but had nothing remotely close to the relative market penetration of modern media. Canadians of the time lived in a media desert by comparison to their modern counterparts, who are deluged with messages from social media, the internet, television, radio, billboards, magazines, and newspapers.

Canadian newspapers had been in existence for some time before the Confederation decades. French Canada had newspapers from the early eighteenth century, and English Canada had newspapers from the time of the first settlers. As English settlements grew, so too did local newspapers. Halifax, Saint John, Montreal, Kingston, and Toronto all had weekly newspapers, and by the time of Confederation there were scores of Canadian weekly news sheets. Every town that boasted even a bi-weekly flyer usually had two papers: one Liberal and one Conservative. Throughout the period, political opinions were held strongly and virtually every Canadian newspaper had a vigorous, politically partisan perspective.

The 1850s saw the beginnings of two major changes in Canadian newspapers. The introduction of the telegraph meant that, within hours, events from around the world were brought to the reading public’s attention. The telegraph was one of the Confederation era’s three key technological developments accelerating the transformation of the country’s character. Along with the steamship and the train, the telegraph helped moved the country from an insular and regional world view to a more global and dynamic mindset. The first use of the telegraph in Canada was between Toronto and Hamilton in 1842. By 1866, undersea cables linked Newfoundland to Ireland. By the end of the period every sizable community in the country was connected to the rest of the world.

The second significant innovation of the era that had its origins in newspapers was the increased use of commercial advertising. The growth of advertising in Canada occurred only a few short decades after industrialization, and it paralleled almost precisely the growth of newspapers. As the supply of manufactured goods in Canada increased, businesses turned to local newspapers to advertise their wares. It was a move that marked the beginning of Canada’s consumer-oriented society. Because of newspapers with their new-found stream of advertising revenue, the country began a pronounced shift to a more commercially oriented culture, one that has remained deeply ingrained in our daily lives. Advertising and an increasingly segmented newspaper industry — which by the 1880s had introduced high-speed web processes, printed photographs, and expanded coverage targeted at numerous segments of the reading public — meant that Canadians began the initial transformation from a frugal rural society characterized by common experiences to a much more individual culture of luxury and consumption.

While Canadian society was showing the very first signs of consumerism, by the end of the Confederation decades, there were notable changes with regard to leisure. Perhaps most importantly, during the later stages of the Confederation era, people, particularly the well-to-do middle classes in cities, found themselves with more time on their hands. As the society became more affluent, personal leisure time grew. And as leisure time increased, so too did interest in group and team sports and sporting clubs. During the latter decades of the period, even individual activities such as skating, hunting, shooting, and snowshoeing were frequently organized in clubs. This probably reflected the period’s long-established tendency for people to view themselves in a group context rather than an individual one. Canadians of the Confederation era were confident in their own identities and had few concerns about alienation or the loss of individuality. Despite initial changes in newspapers’ market segmentation, daily life was still conducted in small groups, and loss of identification in a mass society was not yet seen to be a psychological threat. It was a time when people readily accepted the company of their peers.

Despite the Confederation generation’s undeserved reputation for being restrained and colourless, this member of the Governor General’s staff displayed an indisputable sense of panache dressed in his skating costume.

It was also a time when there were no such things as professional sports in Canada. Entertainment was generally seen to be an active endeavour. Spectator sports did not begin to take on anything like their current importance until well into the twentieth century. In fact, Canada’s national sport was (and officially still is) lacrosse. Lacrosse was a truly Canadian sport given to us by First Nations, and Canadians, mostly in Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, and Ottawa, took up the game with a passion in the late 1860s and 1870s. Playing lacrosse became a form of patriotic expression and banners posted beside lacrosse fields routinely proclaimed it “Our Country, Our Game.” Lacrosse only gradually lost ground to hockey after the Confederation era.

Hockey, which has since become a celebrated national symbol, was in its infancy during the period. Certainly the game as it is played in Canada today had its first formal beginnings in the late nineteenth century. Some credit King’s College School in Windsor, Nova Scotia, with the game’s invention, while others accept it as an article of faith that the game, as we now know it, originated in contests in Kingston among the Royal Military College, the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, and Queen’s University. Not to be outdone, McGill University has staked a claim that their alumni played the first official games in the 1870s. There may be elements of truth in all of these declarations, for the game evolved and unquestionably began to seize the popular imagination during the final days of the Confederation era. What is without doubt is that it has since become a defining national fixation.

Other sports that Canadians played included cricket, curling, and variations of baseball. Baseball, as played in Canada at the time, had various rules; some versions of the game had five bases, used cricket bats, and had eleven players per side. The American version of the game became broadly accepted in Ontario in the 1860s.

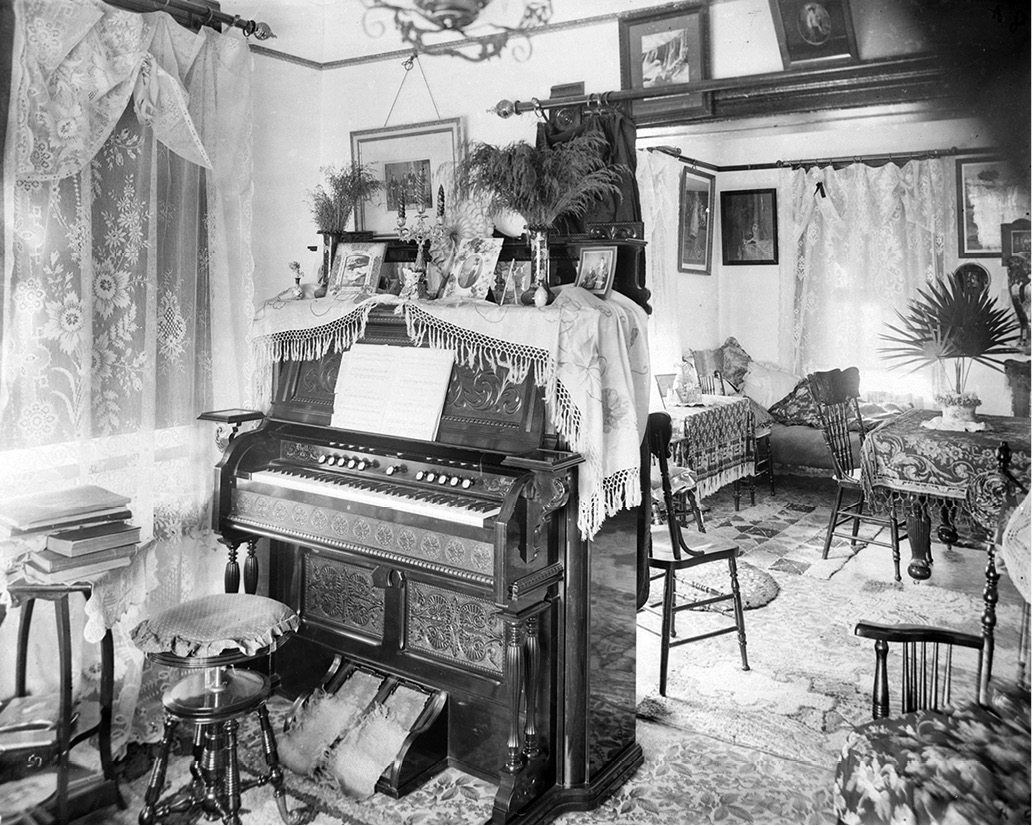

The interior of a middle-class house in Nova Scotia. The musical instrument is a harmonium, or parlour organ, built in Guelph, Ontario, in the late 1860s.

In addition to sports, Confederation-era Canadians participated in the arts on an amateur basis. The country was not large enough to develop its own elite, commercially successful communities until much later, but the period was nonetheless characterized by individuals actively engaging in events rather than observing them. Music is a good example. Love of music was as equally a universal trait in the Confederation era as it is now. With no recorded music available there was much less variety, but lack of variety did not prevent people from making their own music. Singing, for example, was a more popular and accepted pastime than it is now. Having a good voice was a much-prized social blessing, but it wasn’t a prerequisite to having a good time. People sang at home as entertainment, they sang in groups at school and in churches, and they sang without the awkward public discomfort that modern Canadians exhibit when called upon to sing.

Musical instruments were expensive and many years of lessons, although available, were usually only accessible to the affluent urban middle classes. Nevertheless, many families across Canada’s broad middle-class spectrum would have scrimped to own one of the new, mass-manufactured pianos. During the Confederation decades, pianos became central features of social life at home. In the days before the gramophone and the radio, public music was a rarity, so Canadian families made and enjoyed their own music. Group singing, or as it was commonly known, “parlour music,” was a stimulating and creative outlet. It was a wonderful way to relieve stress and was an intensely sociable activity. Parlour music was such a highly valued activity that having the ability to play the piano was considered an important social skill for well-to-do young women.

For a small country, Canada had many successful and high-quality piano and organ manufacturers. It was a vigorous industry, well-supported by Canadian and American markets. And while Canadians did a brisk trade in quality keyboard instruments, free trade with the United States also ensured that Canadians were well-supplied with fiddles, banjos, concertinas, and autoharps. These instruments were commonly played and often passed down from one generation to the next with kitchen and parlour musicians learning to play popular tunes by ear.

Regional music flourished in Canada during the Confederation decades. In French-speaking Quebec and Acadia, the Maritimes, and Newfoundland, distinct local versions of Celtic music remained popular. While in English-speaking Quebec, Ontario, and the West, strong American and British music hall influences determined much of the music that was played.

Home or community entertainment also often entailed amateur theatrical performances, which frequently involved preparing elaborate costumes. Amateur dramatic productions were popular, not the least because they took weeks of intense activity to prepare and rehearse. Drawing on centuries-old English traditions of the village pantomime, Confederation-era Canadians often wrote the scripts and scores for their own theatricals. Sadly, this is a tradition that, except for the locally produced theatrics found in the junior years of grade schools, has all but died out in Canada.

In addition, in the towns and cities, churches and schools often sponsored art exhibitions, drawing classes, textile arts courses, as well as singing and dancing lessons. Reading was a popular form of entertainment, although books were expensive, there were far fewer libraries per capita than there are now, and those that existed during the Confederation decades were fee-based organizations. Tax-supported libraries did not appear in Canada until the first ones were established in Toronto and Saint John in 1883. In many towns there were “Mechanics’ Institutes,” which provided lectures and reading material in an organized attempt to develop adult education.

The Confederation decades in Canada had a vibrant cultural and artistic life, but in keeping with the largely rural nature of the society, it tended to be family- and community-oriented. This situation would remain largely unchanged until the social upheavals of the First World War.