Chapter Five

The Regions and First Peoples: Ontario

Ontario’s territory grew significantly during the Confederation decades. Canada West initially consisted of the Ottawa River Valley, southern Ontario, and a strip running north of the shores of Lake Huron and Lake Superior. By 1880, the province had expanded westward to the current Manitoba border and northward, although it stopped well short of James Bay. Like Quebec, Ontario did not take possession of its northern regions until the twentieth century.

Unlike Quebec, which had slower economic and demographic growth prior to the Confederation decades but more far-reaching social change, Ontario’s growth rate was considerably swifter, more dramatic, and somewhat more predictable. In the early 1840s, Canada West had a population of about 480,000. By the end of the Confederation decades, it had grown by nearly 1.5 million people. This phenomenal increase was due almost entirely to a continuous stream of immigrants arriving from England, Scotland, Ireland, and the United States.

Despite the tidal wave of immigration, by current standards Ontario was not a very diverse province. By the end of the decade, the population would self-identify for the census takers as being: 42 percent Irish, 32 percent English, 24 percent Scottish, and 3 percent Welsh; 159,000 were German, and 75,000 were French. It is worth noting that for census purposes, aboriginal peoples failed to make the list altogether, while the officials who administered the census, perhaps to hide the fact that the province was in danger of being culturally overwhelmed, decided that “American” did not qualify as an option for national origin.

In terms of religious beliefs, Ontarians of the period were overwhelmingly mainstream Christian: 29 percent professed to be Methodist; 22 percent Presbyterian; 20 percent Anglican; 17 percent Catholic; and 5 percent listed themselves as Baptist.1

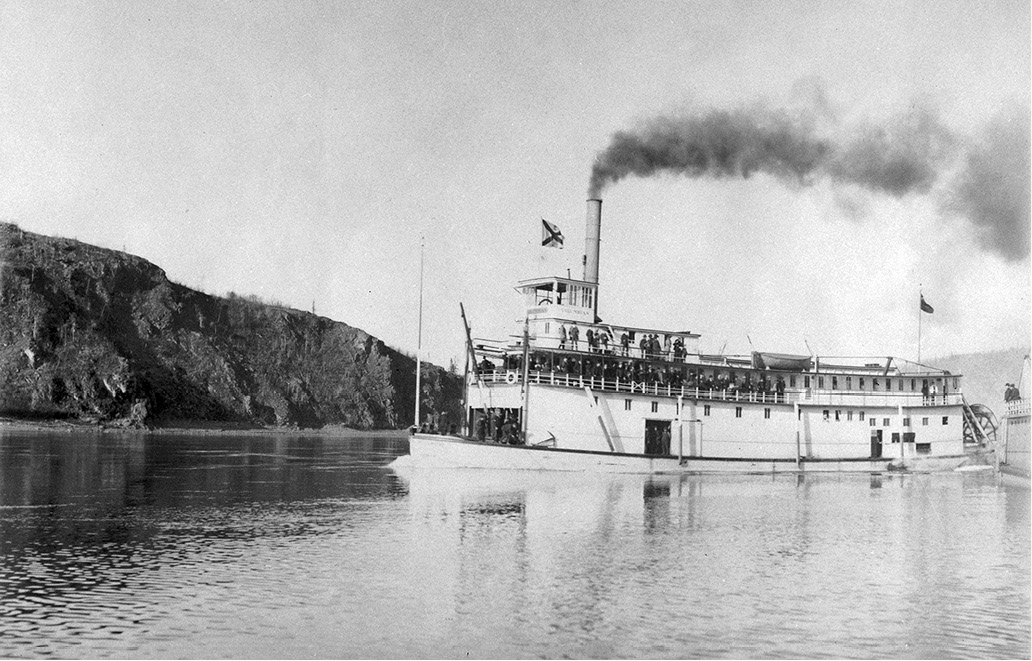

The province’s industrial development moved at a pace as brisk as its explosive population growth. Industrial expansion was largely due to the steady improvements to Ontario’s transportation systems and its internal communications. The distances that had to be covered when moving goods and the rugged nature of Ontario’s forested areas meant that the simplest and most economical means of transportation was via waterways. The St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes were easily navigable, and throughout the Confederation decades steamships provided ready access to the ports of Montreal and Quebec City. Steamboat travel was well-established by the early years of the Confederation era. The very first steam-powered ships appeared on the St. Lawrence waterways as early as 1816, and by 1840 iron-hulled steamers were running directly from Lake Ontario to Montreal.

The canal systems, so essential to linking major waterways, were based on the ancient First Nations and fur trade portage routes. Initial construction on most canals had been completed prior to 1840. The development of Ontario’s canals was closely connected to the lucrative trade in wheat farming. Most Canadian grain was grown in Ontario and getting it to market overseas required canals so that the grain could be shipped from Lake Ontario and Lake Erie to get it to the port of Montreal. This feverish canal construction resulted in almost all of Ontario’s major towns being connected by regular, reliable, and relatively cost-effective water links.

Canal construction finally ended in 1848, which conveniently dovetailed with a surge in railway construction. Nonetheless, prior to the completion of what would become a dense network of railway lines in Ontario, steamboats provided the backbone of the province’s transportation system. In fact, most of Ontario’s principal towns during the Confederation decades were serviced by steamboats with well-appointed dining rooms, salons, and comfortable cabins.

Despite the comfort, steamboat travel on the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River was not without its own unique perils. At the time, there were few reliable nautical charts of the Great Lakes system, and in the sudden and violent storms so common on these waterways, groundings and shipwrecks with large-scale loss of life were regular occurrences.

Despite the periodic catastrophes that attended travel by water and the existence of stage coaches, using Ontario’s waterways was for years the preferred means of transportation. The province’s meagre road system was notoriously awful, and travelling on existing roads, even in good weather, was always problematic. Building roads in Ontario was expensive and the inevitable potholes, flooding, bogs, frost heave, and washed-out culverts that developed once the roads were built meant that they were even costlier to maintain. As a result, the transport of goods, people, and mail relied heavily on steam boats and later railways.

A Great Lakes steamboat near Toronto, 1860s.

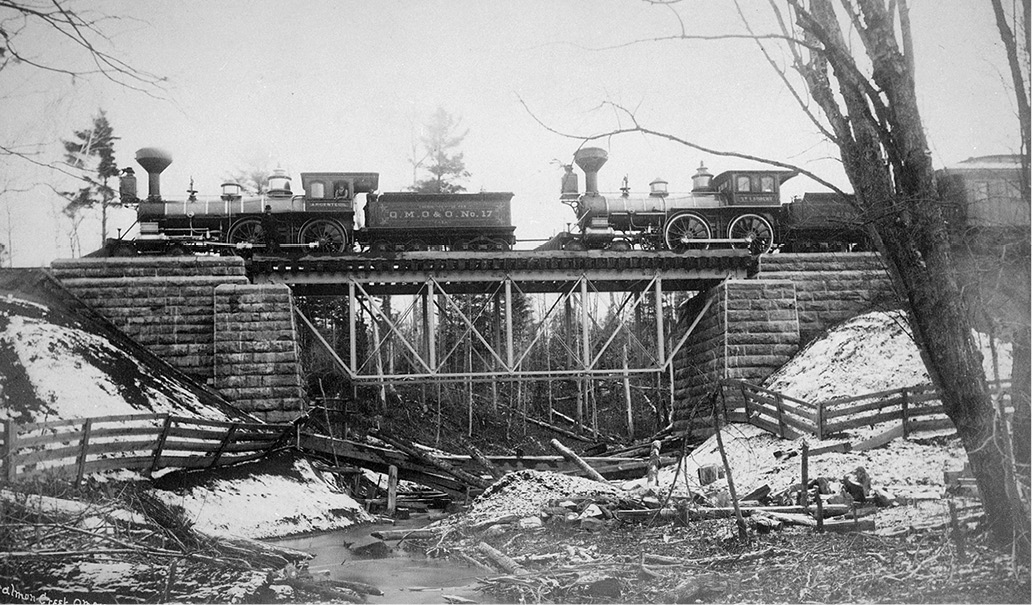

Ontario’s rail lines sprouted like spring weeds during the Confederation decades. Early on, they provided fast, efficient linkages between Toronto, Montreal, and Sarnia, as well as connections to American markets. Rail links to the United States were increasingly important, for with the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, Ontario farmers and merchants vastly increased their trade in grain, lumber, fruit, and manufactured wares to the northern states. By the end of the period, Ontario’s network of rail lines would cover a dense web, providing linkages as far west as Sault Ste. Marie, with connections east into Quebec, south to the United States on several crossings, and to all the province’s major cities and towns.

Ontario’s Confederation-era railways and waterways carried people, lumber, minerals, and a range of manufactured goods; but their most important cargo was the province’s agricultural produce.

Trains on the Ottawa–Montreal Line, 1878.

Farming employed the vast majority of the population in Ontario. Farmers, if they weren’t tenants, usually owned the land they tilled. Unlike the seigneurial system that was phased out in Quebec, Ontario’s farmers operated on the basis of “free and common socage,” an ancient and quaint term for the practice of purchasing one’s land and having land ownership treated in the eyes of the law as normal personal property.2 It is unlikely that the system of land ownership had much effect on the agricultural productivity of farmers in either Ontario or Quebec. However, there were significant differences in the profitability of the farms in Ontario and Quebec.

During the first three decades of the period, agriculture was three times as profitable for farmers in Ontario as it was for those in Quebec.3 This substantial difference was due to a number of reasons. In Ontario, the land itself was more fertile. At the time, modern farming techniques were not in use anywhere in Canada. Practices such as crop rotation and the use of fertilizers would not become common for many years. Thus, Ontario farms had not been subject to the same period of soil exhaustion as had the much older and more extensively tilled Quebec farms. Additionally, Ontario farmers were quicker to move away from subsistence farming. With more diverse and developed transportation links into populous American markets, Ontario farmers could more readily export surplus production to the United States.4 Accordingly, Ontario farmers took advantage of the greater incentives to specialize in their agricultural production and they began raising high-volume crops for external markets.

The business of farming in Ontario during these years was also slightly more complex than it was in Quebec. In Quebec, at least for the early years of the period, farmers on rented land tended to follow the long-established agricultural practices in use during the seigneurial system. On the other hand, in Ontario during the Confederation decades, land-owning farmers were quicker to adopt new machinery and improved processes, and, as a result, agriculture in Ontario developed more rapidly into a complex industry. It is important to note that the distinctions between the two provinces were not the result of innate cultural differences. By 1840, most Western societies had adapted many of the innovations of the Industrial Revolution. In Ontario, by virtue of its more recent origins, there was far greater economic specialization and innovation than had existed when the bulk of Quebec’s farmland was opened up. In Ontario, specialization in the agricultural industry had four distinct, associated components.

At the front end of this growing industry was land sales. Land sales and land speculation were highly lucrative businesses for both the government, which allocated undeveloped lands, and the small number of individuals who sold existing farms. Once forested land had been purchased, clearing the land and removing its stumps was essential to make the farm productive. Large-scale stump removal was a major undertaking, and it evolved into its own unique and specialized business (for more on this, see Chapter 13). The third component of this growing industry was actually farming the land itself; and just as in Quebec, 80 percent of Ontarians were farmers. The final component, shipping the harvest to market, was probably the most profitable and capital-intensive function of the agricultural business.5 Much like the modern farm industry, the Confederation-era farmer found himself to be the least profitable link in the agricultural chain.

Farmers at work in an Ontario farm field, 1860s.

Farming in Ontario, on the small family farms of the period, was a precarious occupation. The main commercial crop was wheat, but wheat was a boom and bust commodity. Fickle markets and uncertain harvests meant farmers had to hedge their investment by planting alternative crops. It was a difficult business, and most Ontario farms survived the lean years as self-sufficient operations, capable of producing enough fruit, vegetables, grain, and livestock to provide for the needs of a large family. However, in years when the crop yield was good, they regularly produced wheat surpluses that could be sold as an export product.

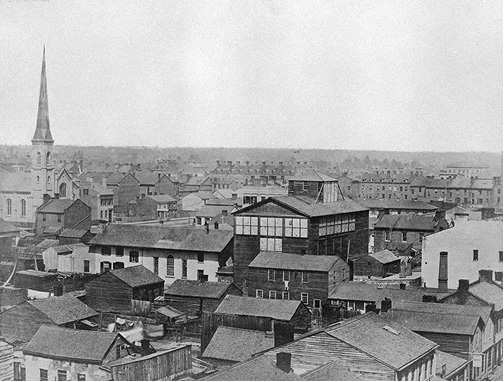

Ontario’s towns and cities were in their infancy at the outset of the Confederation decades. In the 1840s, Toronto, which had for years been a sleepy outpost settlement, suddenly began to grow. Its growth was stimulated largely by the bustling steamboat operations that ferried people and goods from Montreal and the numerous towns and villages in between. By the 1850s, the steamboat trade, which was seasonal, was overtaken by the railway boom. Because railways could operate year-round, in winter and summer, in good weather and bad, trainloads of new immigrants could disembark at Toronto’s new Grand Trunk Railway station at the corner of Bay and Front Streets. This railway boom, in turn, spawned numerous other industries and related services.

In the four decades of the Confederation era, Toronto’s population tripled. The city began the period with only thirty thousand people, but ended with over ninety thousand residents. It wasn’t until the following decade that Toronto would experience a truly explosive growth phase, seeing the population double again by 1890.

Toronto, early 1850s.

Toronto was a new kind of colonial city in an expanding British Empire. In 1851, 97 percent of the population claimed their family origins in the United Kingdom, with only a third of them being Canadian-born. By 1871, these numbers had changed. Almost three-quarters of the city remained Protestant and almost everyone’s family hailed originally from the British Isles, but after Confederation, a clear majority claimed to be Canadian-born. By contemporary multicultural standards, Confederation-era Toronto was monotonously uniform; but it was, in fact, a highly stratified mix of discrete economic classes, religious sects, and social divisions.

Toronto was much less sophisticated and fashionable in the Confederation era than Montreal. Montreal was larger and older — a more established city, with a larger trade sector, established institutions for the arts and higher education, parks, and links to America and Europe. Montreal had a more cosmopolitan air. But Toronto was certainly not the dull “Hog Town” that many of its modern critics and detractors would love to have the rest of Canada believe. Far from being “Toronto the Good,” a placid and staid citadel of Victorian rectitude, Toronto was an energetic and dynamic society with its own sense of colour and a unique set of social problems. For example, throughout the Confederation era, unilingual Toronto, with its two factions of Protestant and Catholic Irish, had far more ethnic and sectarian tension than did Montreal with its French-English divide.

As Toronto transformed industrially and commercially, the city’s social structure also changed. Prior to the revolution of 1837, Ontario’s leaders were drawn from Upper Canada’s tightly knit “Family Compact.” The members of the Family Compact were all male and came from the government, the established professions, and the clergy. Although the leadership’s gender remained the same, during the Confederation decades the most powerful class of people changed drastically. Particularly in Toronto, a new class of influential leaders arose. The city’s most prominent leaders now came from an ascendant commercial-industrial elite. A newly enriched generation, with families such as the Eatons, the Masseys, the Gooderhams, and dozens of lesser-known figures, rose to prominence in the social and business realms. They were largely self-made men who had achieved success as entrepreneurs, tycoons, and industrialists, and they brought with them a new set of purposeful and enterprising attitudes.

As the stolid colonial city on the frontier gave way to the more bustling and industrialized profit-oriented society, so too grew its middle and working classes. Drawn largely from Protestant English and Scottish immigrants, Toronto’s “bourgeoisie” became a relatively well-established and successful group, one that thrived with the city’s years of growth, stability, and development. Again, as in Montreal, in Toronto an Irish underclass sprang up from the new wave of impoverished but determined immigrants who arrived in the late 1840s.

However, for the poor, whether they were wellestablished or newly arrived, there was little in the way of help. Except for a few faith-related charities, social services in Toronto were virtually non-existent and much of the urban working- and under-classes lived in desperate conditions. Unemployment, illness, old-age, and disabilities often meant personal catastrophe for Toronto’s urban poor.

Ottawa, which was originally a part of the hunting grounds of the Algonquin First Nations, was first settled by Europeans in the early 1800s as a farming and logging community. By 1840, the original settlement, which was named Bytown after Lieutenant Colonel John By, the British Army engineer who built the Rideau Canal, had grown to three thousand people.

Bytown was originally a lumber town; it served as the principle location to dismantle and rebuild the lumber rafts that were floated down the Ottawa River to get them past the Chaudière Falls. In the earliest years of the Confederation decades, the town’s major businesses consisted of one lumber mill, a tannery, two foundries, three breweries, and a distillery. The ratio of breweries and distilleries to other businesses perhaps provides some indication of the town’s early character.

By 1845, Bytown’s temperament was changing. It could boast a further thirty-eight shops and stores. Its growth was steady, if not spectacular. It became a waypoint for transient loggers, and a network of retail businesses grew up, selling pork, flour, and general supplies to the lumber business. By the end of the 1840s, Bytown’s service sector expanded further, and its numerous taverns, gaming houses, and brothels did a thriving trade.6

Like so many Canadian towns of the period, Bytown was populated with a mixture of English, French, Scottish, and Irish. With this mix, life in Canada’s rough future capital wasn’t always placid or peaceful. In Ottawa, much like Toronto, many of the earliest English and French settlers resented the arrival of Irish labourers. There were periodic riots and the town’s early years were wracked by simmering low-level sectarian violence.

The gentrification of this rowdy frontier town came through good fortune. The town changed its name to Ottawa in 1855; and in 1857, Queen Victoria, peering at a map, noticed it straddled the borders of Ontario and Quebec — and sat at what was thought to be a militarily safe distance from the United States. With little further ado, she chose it to become the capital of a unified Canada East and Canada West. By 1866, Ottawa had sprouted a handsome new set of Parliament buildings, replete with the latest and most modern construction innovation — central heating. The bill for the new Parliament and a fine collection of neo-Gothic buildings to house a growing civil service was completed for a grand sum of $625,310. For the next fourteen years, government, railways, and an ever-expanding lumber business helped the city grow. The nation’s capital ended the Confederation decades as a small city of just under thirty thousand people.

Other Ontario communities of the period, such as Hamilton, London, and Peterborough, were in their infancy during the Confederation era. Each of these towns had regional importance as centres for local retail, as well as small-scale manufacturing, agriculture, and the lumber trade, respectively. However, for them, economic growth during this period was more gradual than that of Toronto and Ottawa. Growth in most of these cities, which today are classified as mid-sized, would not accelerate until the early and mid-twentieth-century manufacturing booms.

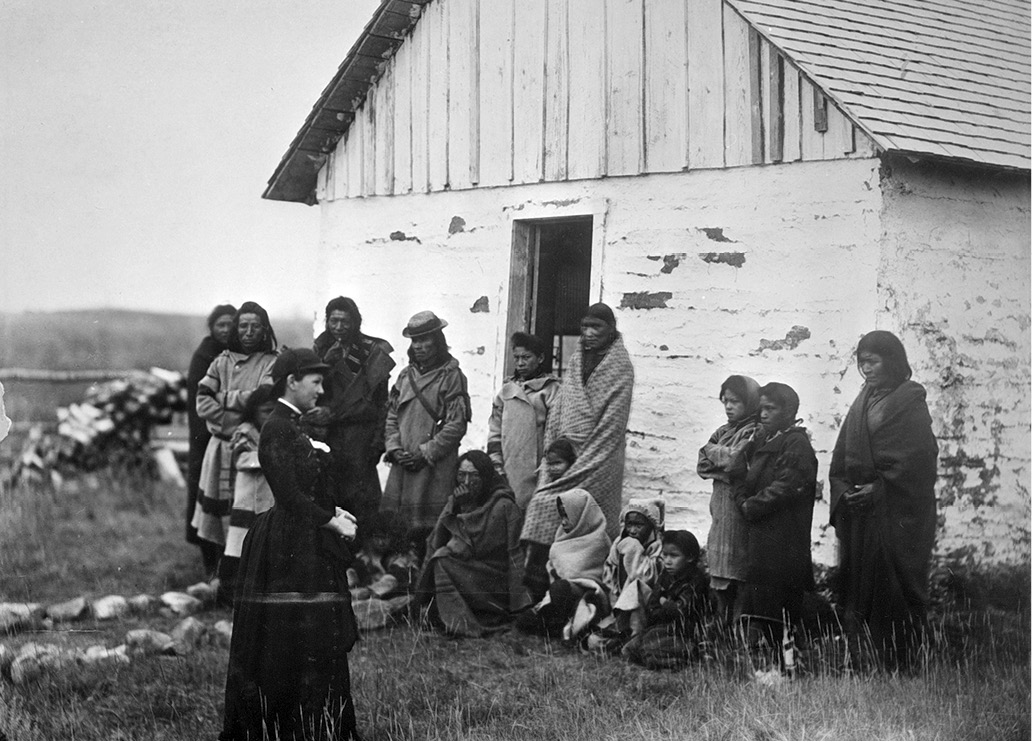

Throughout the Confederation decades, while the cities grew and the farms prospered, governments in Ontario ignored the region’s First Nations peoples, administering them under the authority of several different kinds of programs. Virtually all of them were either damaging or inefficient.

During the 1830s, following petitions from several aboriginal groups, a British parliamentary inquiry investigated the status and conditions of aboriginal peoples in Canada. Its report clearly stated “that unregulated frontier expansion was disastrous for Native peoples.”7 At that time, the Colonial Office in London handled aboriginal affairs and made it their practice to manage aboriginal issues on a regional basis. The rationale for this was that they believed policies should be designed to accommodate the local conditions of each colony.

In the 1830s, the Government of Upper Canada toyed with the concept of creating “model villages.” These were villages where the First Nations would be allocated land and provided with houses and farm equipment. Several model villages were attempted, but most failed. The failure of these model villages was due to insufficient training being provided to prospective indigenous farmers and the issuing of shoddy and inadequate equipment. The program was finally undermined by the unchecked encroachment of aboriginal lands by white farmers. There were, however, a small number of notable successes. In places like the settlement on the Credit River, First Nations were provided fertile land, state of the art equipment, and, most importantly, sustained, supportive mentoring. This, combined with dynamic aboriginal leadership and an indomitable will to survive, meant that these few reserves became models of successful adaptation to farming life.

In the late 1830s, the lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, Sir Francis Bond Head, devised a plan to create large reserves on the Manitoulin Island archipelago and on the Bruce Peninsula. Bond Head’s rationale for creating these large reserves was not to assimilate the First Nations, as had previously been the case, but rather to isolate them from white society. He believed that previous attempts at assimilation, such as the model village program, had not only been failures, but that they were “the most sinful story recorded in the history of the human race.”8 He believed that contact with European settlers had always been to the detriment of natives and that segregating them would be a “kindness.” Bond Head’s conclusion was that First Nations were better off living by themselves on remote reserves. When his plan was implemented with a group of Ojibwa, they ended up surrendering millions of acres of rich, arable southern lands for tracts of granite and bog in the Canadian Shield. Agricultural support for the affected groups eventually dried up.

Later, in 1850, Sir Charles Bagot led a commission urging centralized control of aboriginal issues. Bagot’s commission, amongst other things, noted that First Nations were not being compensated, as per the Royal Proclamation, for surrendered lands. He made a few elementary recommendations on a range of matters, such as ensuring the proper registration of aboriginal title deeds; he put measures into place so that First Nations would be compensated for timber harvested on their lands; and he set up a system to provide livestock, agricultural implements, seeds, and furniture to the entire tribe to replace the practice of giving band leaders the traditional armfuls of personal presents. Bagot’s commission was well-intentioned and resulted in improved legislation that went some way to protecting indigenous peoples. It set aside lands to be used as reserves, provided legal protection from the predations of loggers, and created a system that revitalized the compensation process for surrendered lands. However, Bagot also made the ominous recommendation for the development of residential schools. He envisaged a system where First Nations children, when “isolated from the influence of their parents … would imperceptibly acquire the manners, habits and customs of civilized life.”9

A residential school in Ontario, 1860s.

It was argued that residential schools would provide a progressive and enlightened approach to solving what was believed to be the intractable issue of “civilizing the Indian.” Egerton Ryerson is widely and justly acclaimed for his progressive role in developing Ontario’s educational institutions. He was also an influential advocate for residential schools. He believed in a school system for First Nations separate from the school systems for whites, one that catered to the unique needs of First Nations. In the absence of any other racist views on his part, and given that the much-stated aim of assimilation was seen to be, at the time, an undisputed benefit to be conferred upon aboriginal peoples, it is possible to see that the residential school system was not developed out of malice. Rather, its creation reflected the authoritarian, insensitive, and arrogant thinking of the time. This, after all, was the age of the work house, public hangings, and survival of the fittest. As with every other initiative involving aboriginal affairs, the views of First Nations were not taken into account, nor was any thought given to just how such schools would be administered or overseen. It was a deeply flawed idea disastrously implemented. Residential schools did not become widespread until the mid-1880s, but the germ of the concept took root in the early days of the Confederation decades.

In 1857, Sir John A. Macdonald sponsored “An Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indians of the Canadas.” The act outlined the process by which First Nations people could become full citizens and given the vote. To do so, the individual had to be male and over the age of twenty-one. He had to be literate in English or French, have “minimal education,” and not have any debts. He had to be able to prove he was “of good moral character” and submit to a three-year probationary period. If the individual met all these criteria (measures that were never even remotely contemplated for white people), the tribe was to slice off over fifty acres of arable land from their reserve for the individual’s exclusive ownership. Aboriginal leaders wisely saw this as an attempt to destroy their culture and to undermine the integrity of existing reserves. In the end, the act was a dismal failure as disdainful indigenous men overwhelmingly spurned the program.

In 1860, responsibility for the administration of First Nations passed to Canada from Britain. Prior to this, the Crown had concluded numerous treaties with various aboriginal groups. The effect of these, which covered all of Upper Canada, was the transfer of virtually all the land area of Ontario to the government, in exchange for granting title to a few reserves and the promise of a limited range of goods and services. By 1873, with the expansion of Canada to include not only the original provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, but also the North-West Territories, Manitoba, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island, Canada’s aboriginal population jumped from twenty-three thousand to over one hundred thousand people, while at the same time adding hundreds of new tribal groups.

As a result, the Indian Act was introduced as a means of consolidating and standardizing the government’s administrative processes dealing with the country’s aboriginal population. As we shall see in Chapter 7, which deals with the Prairies, the Indian Act was written without significant aboriginal input and was never designed to promote fairness or reconciliation. It was written in the spirit of the times with the presumptuous good faith and high-handed assurance of an imperialistic society. As a piece of enduring legislation, it reflected a popular, paternalistic, chauvinist, and impatient Victorian world view, one that sought neither fairness nor reconciliation, but aimed to bring about the rapid assimilation of the aboriginal population.