Chapter Six

The Regions and First Peoples: The Atlantic Provinces

Prior to the Confederation era, the Atlantic provinces had been governed under a number of French and British colonial administrations. The most dramatic change in colonial administration came with the end of the Seven Years War in 1763, when the Treaty of Paris ceded the hardy and self-reliant Acadian colonies in P.E.I. and New Brunswick to Britain. This momentous transition to British rule initiated a pattern of immigration that was to alter the cultural makeup of the Atlantic provinces for more than a century and a half. Under British rule, English, Irish, Scots, Germans, and Americans moved to the region in relatively large numbers, leaving an English-speaking majority with regional enclaves of French-speaking Acadians.

With the exception of Cape Breton, which had for a brief period been an independent colony but rejoined Nova Scotia in 1820, Atlantic Canada’s colonial governance structure remained relatively stable. By the outset of the Confederation era, the region was organized along the lines that we are familiar with today.

Nova Scotia, in 1848, became the first of the British North American colonies to achieve responsible government. The colony had a pronounced independent streak, and in the run-up to Confederation there was a stubborn and determined group who, for reasons of regional pride and well-established business connections, bitterly resisted joining the union with Canada. Nova Scotia’s traditional trading ties had been, via seaborne trade, with New England and Britain. For a sizeable minority, the concept of throwing their future in with Quebec and Ontario seemed not only counter-intuitive and foolish, but economically suicidal. However, the case favouring union with Canada prevailed. The fear of being swallowed up by the Americans persuaded the majority to go along with Confederation. Given the province’s recent history, this was an issue with a special pertinence for Nova Scotians, for in the immediate post-Civil War years, many Americans were less than pleased with the fact that Nova Scotia had done a brisk and profitable trade with both the North and the South throughout much of that conflict. There were other reasons favouring union: the Fenian threat, the cancellation of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States, and the promise of railways linking Nova Scotians to new and growing markets in Ontario and Quebec all played their part in convincing Nova Scotians to join Canada.

The new union also came at a time of declining fortunes in both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The two provinces had developed strong lumber trades, which in turn spawned vigorous local shipbuilding industries. By the early 1850s, the shipyards on New Brunswick’s rivers were producing a hundred ships a year. By 1875, more than five hundred oceangoing ships were built in Canadian shipyards, most of them in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. And by the end of the Confederation decades, Canada, with more than seven thousand registered ships, was the fourth largest ship owner in the world.1 It was a golden age, but it would not last. Technological change would soon make wooden sailing ships obsolete. With tentative beginnings in the early years of the Confederation decades, the world’s shipbuilding industry began to modernize. Exploiting the use of copper, iron, and steel composite hulls, this lucrative trade began slowly shifting away from Canada to Northern Ireland, northern England, the Baltic, the Mediterranean, and America’s eastern seaboard.

Nova Scotia’s decline in shipbuilding overlapped with its development as a coal producing region. Cape Breton shipped coal to Ontario and Quebec via the Intercolonial Railway and by ship, using the recently re-dredged and deepened St. Lawrence shipping channel. Cape Breton coal became a vital commodity in the growth of a newly united country, but the large-scale industrialization that coal supported was of much more benefit to Ontario and Quebec than the Atlantic provinces. Fishing, lumbering, and mining continued to be the economic backbone of both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

For much of the Maritimes during the Confederation era, agriculture remained largely at a subsistence level. However, there were exceptions. For example, the Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia began intensive and profitable farming of apples, finding markets in the other provinces, Britain, and the U.S.A.

Regional farming in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick often supported the lumber industry. The thousands of work horses that worked winter and summer in the provinces’ forests consumed immense quantities of hay and oats. Each of the massive Clydesdales, Belgians, Shires, and Percherons that became the logging industry’s pride ate literally tons of hay and oats each year. Catering to the draft horse market, many farms that would otherwise have been subsistence operations turned to these basic but profitable cash crops.

Local demand for wheat, which had never been a major cash crop in Nova Scotia or New Brunswick, was virtually eliminated in the Maritimes as the newly built railways brought in cheaper grain and flour from Ontario. For a brief time, P.E.I. struggled on as the exception to this set of circumstances. The Island’s farmers had had the distinction of being the first from any Maritime province to register an agricultural surplus when they began exporting wheat to Britain as early as 1831. It didn’t last, but during the Confederation era, P.E.I. found its niche.

A New Brunswick farm in the late Confederation period.

Potatoes, grown in the province’s distinctive red soils, had always been an important crop. However, it was during the Confederation era that potatoes steadily became the province’s most valuable cash crop. In an export boom that has endured as long as Canada, P.E.I. farmers in increasing numbers specialized in raising potato crops. They began shipping potatoes to every other province, the U.S., and the Caribbean — and in doing so did much to ensure that P.E.I. prospered as a steady, self-reliant, and modestly comfortable rural society.

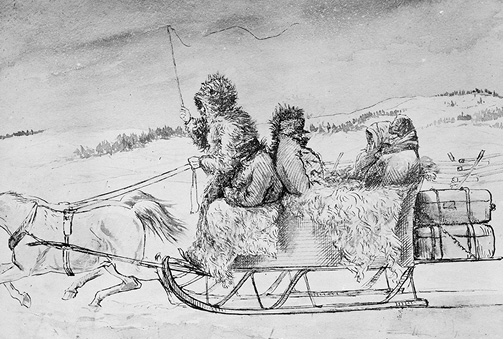

A cold journey, the most common form of winter transportation before the arrival of the railway.

The Maritimes’ two major cities during the era were Halifax and Saint John, New Brunswick. Halifax had a long and colourful history as an important naval base, a function it retains today. The city prospered during the American Civil War. Part of the reason was that Haligonian merchants did a brisk business supplying the wartime needs of the North; at the same time, they provided a sanctuary and a base for the resupply of Confederate blockade runners — which is not to say that most of the population were strong supporters of the South. Since the arrival of freed slaves who fought for the British in Loyalist times, Halifax has had a sizeable black population, and there was virtually no support for the institution of slavery. Most of the population sympathized with the North, and scores of the city’s young men who had personal and family links with New England chose to serve in the Union Army.

Halifax’s growth was a result of several factors: its importance as a military and naval base, shipbuilding, its status as a colonial and provincial capital city, its deep-water port (mainland North America’s closest port to Europe), and the lumber and fishing industries all contributed to its prosperity. However, for some Halifax merchants, Confederation proved to be a disappointment. The growth of heavy industry and manufacturing that had been hoped for failed to materialize, and the railway links to the American ports of Boston and Portland siphoned off much of the anticipated shipping business from Quebec and Ontario.

To the south, on the Fundy Coast, just prior to the Confederation decades, Saint John, New Brunswick, was Canada’s third largest city. Originally a bastion of Loyalist Protestants, its character was changed forever with the arrival of large numbers of Scots, followed by Irish fleeing the potato famine. Its status as a port, along with its lumber and shipbuilding industries, had seemed to guarantee it a gilded future. However, it was not to be. Despite slow but steady economic growth from the 1850s to the 1870s, the decline of shipbuilding was the first symptom of looming economic torpor and slow growth. Recovery was dealt a punishing and unforeseen blow when the city’s luck turned to disaster in 1877. A warehouse fire spread out of control and, in a nine-hour conflagration, destroyed 40 percent of the town’s buildings. Almost all the damage was in the business district.

Because of the city’s relatively weak economy, most immigrants who disembarked in Saint John did not stay, but chose to board trains for a more promising future in Ontario and Quebec. To make matters worse, Saint John and New Brunswick experienced a sizeable exodus as many young people moved south to New England in search of steady work and higher paying jobs.

Although Newfoundland shared many characteristics with the other Atlantic provinces, its history and culture differed in many ways. Throughout the Confederation era, and for several decades after, Newfoundlanders did not identify with mainland Canadians. They saw themselves as an inextricable part of a British North Atlantic community and regarded all of North America as being politically and culturally foreign. In addition to this idiosyncratic attachment to the old country, most Newfoundlanders had a passionate sense of their own identity, and had no intention of diluting their identity or traditions with those of mainland Canada. This wasn’t a reaction to pressure to join Confederation. Newfoundland’s unique sense of self was firmly established. As early as 1840, it was the only colony to create its own national flag.

Regardless of Newfoundland’s distinctive character, its population was still deeply divided, with communities split along sectarian lines. Notwithstanding some valiant attempts by politicians to bridge the rift between the various communities, English and Irish Newfoundlanders for the most part viewed one another with deep distrust, and Protestants and Catholics remained fervidly split into two guarded and uneasy communities.

Intercommunal suspicion and hostility invariably distorts any society’s collective common sense. Newfoundland was no exception. In the mid-nineteenth century, the island’s sectarian split made for bizarre politics. Politicians campaigning in the 1850s argued that responsible government would be a disaster for Newfoundland, because it would ultimately give control of the legislature to the Roman Catholics. A few years later, many of Newfoundland’s Irish Roman Catholics fought equally as spiritedly, and more successfully, against union with Canada, on the grounds that Irish Catholics had already gained home rule in Newfoundland. Why would they ever want to risk losing it by uniting with Ontario, which everyone could see was a nest of anti-Catholic bigotry. In the old country, union had been a devastating experience; why would any sane person ever want to repeat this catastrophe?

Fortunately, with the passage of time and a more tolerant social disposition, virtually all the acrimony and suspicion between the various factions in Newfoundland has long since disappeared. And while it is true that bigoted attitudes flourish in isolated circumstances, other more positive attributes do as well. In Newfoundland’s case, many of these qualities survive today as characteristic features of the province’s people. Hardiness, generosity, warmth, endurance, and a cheerful, open disposition were all molded through decades of privation and peril in the island’s small outport communities.

Those positive Newfoundland traits were rooted in a difficult lifestyle. Life in the outports in mid-nineteenth-century Newfoundland was a hard grind. It created a people who had to be mentally tough and resilient if they were to survive. Illnesses from malnutrition were common, and the mortality rate from disease and work-related accidents was high. The fishing and sealing industries employed close to 90 percent of the population; and most of the colony’s 162,000 people lived in small, isolated fishing communities perched on the edges of Newfoundland’s bays and anchorages.

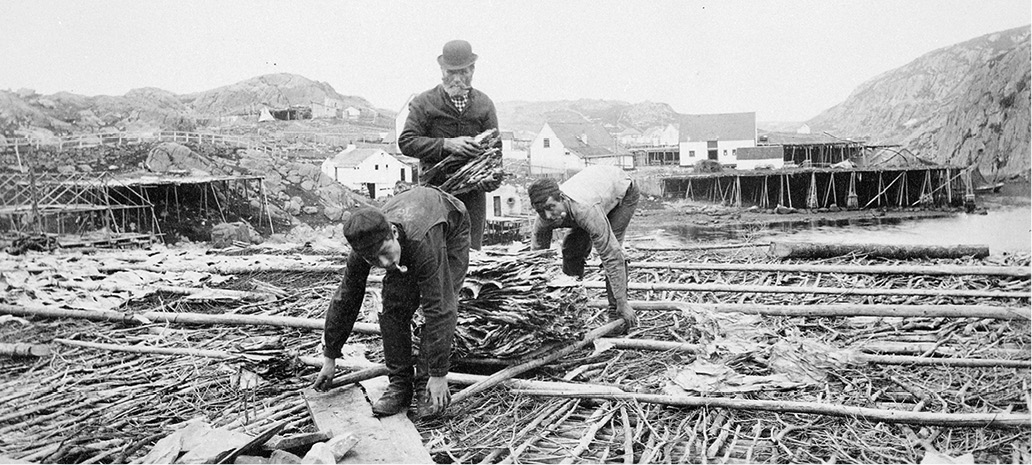

Contemporary accounts of Newfoundland’s outports invariably described similar scenes. Each village was generally located on a small harbour, most often with one or two schooners and numerous fishing boats riding at anchor. On the wooden quayside would be a few unpainted sheds draped with fishnets laid out to dry. Close to the dock were rows of fish flakes, and frameworks of poles and boughs covered in drying cod. Higher up on the rocks and grass-tufted slopes were square, two-storey wooden houses, and beside each was a scrupulously cultivated patch of kitchen garden, planted with cabbages and root crops to provide variety and nourishment for diets that were all too often deprived of essential nutrients. Newfoundland, with very little good farmland, had virtually no market farming, and costly agricultural imports came mainly from Britain and the United States. Trade with the rest of British North America was minimal.

Seasonal migration was a feature of outport life. In the spring and autumn, Newfoundland men regularly moved inland to cut wood and hunt caribou. In the summers, when the North Atlantic was relatively calm, they went to sea — most often in sixteen-foot open dories for the inshore fishery, or in twenty-five-foot schooner-rigged jack boats when they fished the outer headland waters. In the winter, life took a more hazardous turn when men from the outports moved in large numbers out onto the ice floes to hunt harp seals. It was a gruelling existence.

Drying and stacking codfish in a Newfoundland outport village, 1880.

St. John’s was the only Newfoundland town of any size during the Confederation decades. During this period, its population tripled in size, growing from just over ten thousand people to thirty thousand. One observer described the capital at the outset of the period as being made up of:

Large stone houses, good-sized churches, chapels, and court-houses: shops built of wood and painted white, a tolerably regular street, and a road or two, mark the seat of greater wealth, and a more numerous population. Even in St. John’s however fish flakes are by no means entirely absent, though they are confined to the south side of the harbour and to a small nook bearing the euphonious appellation of Maggoty Cove.2

Just as life was never easy for outport villagers, St. John’s had more than its share of disasters. The city was destroyed by fires five times during the nineteenth century. Confederation era Newfoundlanders suffered more than their share of tragedy and hardship. But if life was hard for the descendants of the island’s European settlers, it was considerably worse for the indigenous population.

Except for the Beothuk in Newfoundland, the experience of aboriginal Canadians in Atlantic Canada was in many ways similar to First Nations in Ontario.

Little is known of the original indigenous people of Newfoundland, the Beothuk. They were believed to be an Algonquin-speaking people, who numbered somewhere between five hundred and two thousand people at the time of major European contact. The Beothuk were declared extinct as a people in 1829, as a result of starvation, disease, and conflict with white settlers and Mi’kmaq First Nation populations. With the arrival of white settlers, the Beothuk had moved inland, away from their traditional lands where they hunted for seal and caribou. Inland, their numbers fell drastically — a result of the combined effects of losing their original hunting areas and the effects of disease on the population’s hunting-age males.

By the beginning of the Confederation decades, Newfoundland’s remaining aboriginal peoples were Mi’kmaq. Whether or not the Mi’kmaq were native to Newfoundland or not is a contentious issue. Some argue they came to Newfoundland from Cape Breton after the first white settlements; others claim they were living in Newfoundland alongside the Beothuks centuries before. However, by the 1830s, there were believed to be several hundred Mi’kmaq living on the island. With the extinction of the Beothuks, Mi’kmaq bands moved from the southern areas of Newfoundland and into the interior of the island, where they followed a relatively undisturbed and traditional way of life until the very late nineteenth century, when the arrival of railways brought white hunters and settlements into Newfoundland’s interior.

In Labrador, there are three aboriginal groups: the Innu, the Inuit, and the Southern Inuit. The Innu are a part of the Algonquian-language group of peoples and one of Labrador’s two pre-contact aboriginal peoples. The Inuit are an indigenous people who are believed to have migrated from the sub-Arctic south along the coast to Labrador almost eight centuries ago. The Southern Inuit, similar to the Métis elsewhere in Canada, have mixed aboriginal-white ancestry. Descended from Europeans, primarily English fishermen, and Labrador Inuit, they differ significantly from the Inuit and have their own distinctive culture.

The Innu people have historically lived in the boreal forests of Labrador. They speak a dialect similar to Eastern Cree; and until the arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1830, they followed a traditional nomadic hunter-gatherer existence. In the late eighteenth century, with the assistance of Moravian missionaries, many of the Innu converted to Christianity. However, it was the arrival of the fur trade that had the most disruptive effect on the Innu. As they adapted to the benefits of this new economy, they ceased being nomadic caribou hunters and moved to more permanent village locations. Instead of a nomadic hunting life, they primarily manned trap lines and hunted and fished locally. For many, it was a ruinous change to their lifestyle, as the more permanent settlements often faced periods of famine — the result of depletion of their food sources through overhunting. Their migration also subsequently meant that because they were relatively recent migrants, in the law’s eyes, they were not entitled to aboriginal land settlements. Like all aboriginal peoples, the Innu suffered heavily from introduced diseases.

The Inuit in Labrador had the longest contact with Europeans, with trading first recorded between Labrador Inuit and sixteenth-century Basque whale hunters. By the time of the Confederation decades, the Inuit had become Christians, again through the ministry of Moravian missionaries. Their traditional lifestyle evolved, largely as a result of their contact with European trade networks and the frequent visits of whaling ships.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century and continuing throughout the nineteenth century, along the south coast of Labrador, European fishermen and whalers took Inuit wives and settled along Labrador’s southern coast. By the outset of the Confederation decades, the resulting mixed “Southern Inuit” culture was well-established and displayed many unique cultural dissimilarities from the more northerly Inuit. Although the Southern Inuit have been variously called “Southern Inuit Métis,” or “Labrador Métis,” they are an entirely separate and distinct culture from the Métis found in western Canada.

In the Maritime provinces, various Mi’kmaq and Maliseet tribes made up the largest element of the First Nations populations. Their territories stretched from the south shore of the Gaspé through New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Both the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet people belong to a larger linguistic and tribal grouping known as the Wabanaki Confederacy, which extends well into the United States.

As a result of considerable inter-marriage, the two tribes were initially allied with the French. They both made peace with the British after the Seven Years War. However, because the Royal Proclamation of 1763 made no mention of any of the Maritime colonies, Loyalist settlers assumed that the Maritimes were empty spaces and largely ignored their land rights. Much the same pattern of development followed as in Quebec and in Ontario, with the advance of white agricultural settlements forcing aboriginal migration.

As farming communities developed, nomadic First Nations were squeezed off their traditional hunting grounds, moving to re-establish themselves in more remote and less valuable areas. In all three Maritime provinces, there were attempts to establish First Nations as farmers. However, just as in Ontario, these programs failed — for similar reasons. The programs themselves were badly conceived and ineffectively run. They were insufficiently resourced in terms of training and equipment, and, most distressingly for the unschooled First Nations bands, white farmers were allowed to clear and farm reserved lands that had never been properly documented.

Throughout the Confederation decades, First Nations in the Atlantic provinces were gradually and inexorably thrust onto the margins of white society, eking out their lives hunting and fishing, and finding occasional seasonal employment in the lumber trade, in the inshore fisheries, and later as labourers on the railways.