Chapter Seven

The Regions and First Peoples: The West and the North

Large-scale European settlement of the West took place after the Confederation decades; accordingly, the narrative of the West in this period is a story of small numbers.

By the 1840s, Manitoba had just over six thousand people, the majority of whom were Métis, a community that had been established in the area for over a century. The single largest minority population consisted of Scots living in the “Red River Colony,” which had been formed as a humanitarian project by Lord Selkirk in 1812. Selkirk, a Scottish aristocrat, was deeply troubled by the forced removal of farmers who were evicted from their small farms to make way for sheep enclosures during the Highland Clearances of the early nineteenth century. The Hudson’s Bay Company granted Selkirk a massive tract of 116,000 square miles for his settlement. It was not an act of charity. The company tied three expectations to the land grant: Selkirk’s colonists could not compete in the fur trade; the settlers had to provide two hundred men each year for employment with the company; and the colony had to furnish stocks of meat, flour, butter, and vegetables in order to reduce the company’s shipping costs of supplies from Britain. Selkirk’s settlement, in the area that would later become Winnipeg, was the only major settlement that the Hudson’s Bay Company established in its 1.5 million-acre territory.1

Long before the arrival of the Red River settlers, the Métis were well-established. Métis communities and an independent Métis culture had been in existence and growing in southern Manitoba since the days of the early French fur trade, when fur traders married and co-habitated with First Nations women. At the time of the establishment of Selkirk’s settlement, Métis society in southern Manitoba was based on fur trading, hunting, and farming. It was a unique society, partly nomadic, following and hunting the buffalo herds, and partly settled and agrarian. Many Métis farmers lived in small hamlets and on strip farms built along the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. The collision of the two cultures marked the beginning of a long period of conflict between the Métis, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and, later, the government of Canada.

Salteaux Métis family, 1860s.

In the early decades of the century, the Hudson’s Bay Company tried to control the fur trade by attempting to restrict the Métis from doing business with their rivals, the North West Company. This heavy-handed constraint quickly led to fighting in the short lived “Pemmican War,” when a preventable confrontation between Hudson’s Bay employees and Métis traders working for the rival North West Company turned violent. At what was called the Battle of Seven Oaks, the Métis fended off an assault by men from the Hudson’s Bay Company. In doing so, they killed twenty Hudson’s Bay men, including the regional governor, and lost one of their own. Criminal charges were eventually brought against several Métis leaders in British courts, but all were acquitted. It was an ominous series of events, which poisoned relations between the two communities long afterward.

The pace of settlement in Manitoba was slow from the 1840s through to the 1870s. In Canada, the most desirable location to settle was, until then, Ontario. Nonetheless, central Canadians and the British government were not indifferent to the West. The problem they had was that not much was really known about western Canada. Rupert’s Land, as it was known then, was a vast area, and few people outside fur traders and First Nations knew what kind of plants and what range of animals lived there — or if the area was even suitable for agriculture. Transportation was also an issue and no one knew precisely where railways could be built.

All of this meant that development of the West was slow; however, the same was not true south of the border. What was worrying to the imperial government was that the Americans were already mapping and charting their western frontier, and were talking seriously about building a railway to the coast. It was feared that in the absence of any solid information about the West, the Americans might well lay claim to it.

In the spirit of intrepid amateurism, the Royal Geographical Society received a grant of £5000 from the government and duly commissioned Captain John Palliser, an army officer and gentleman adventurer, to launch an expedition to explore western Canada. Captain Palliser put together a team of geographers, surveyors, botanists, voyageurs, and hunters, and between 1857 and 1860 they mapped, studied, and reconnoitred much of the Prairies, surveying possible railway routes through the Rocky Mountains. They didn’t find a route through the Rockies to the Pacific, but they did vastly add to the geographical and scientific understanding of western Canada. Included amongst Palliser’s numerous findings were such things as: the discovery of a fertile belt in the Prairies suitable for farming and cultivation; the clear conclusion that something had to be done to help the native people of the Plains once the buffalo were hunted into extinction; and, the recognition that putting a railway through to the Pacific might be possible, but it would be prohibitively expensive.

At the same time as Palliser’s team was surveying the West, another small group of men, interested in securing the West for Canada, had moved to the Prairies and settled in the Red River area. These men established what they called “the Canadian Party.” Despite the name, it was less of a political party and more of an obnoxious Canadian lobby group, formed mostly from Orangemen, frontier thugs, and eager land speculators. The Canadian Party made no secret of the fact that it wanted Manitoba to join Canada as a thoroughly English-speaking Protestant province, which was not at all reassuring to the French-speaking Métis.

Back in Ottawa, the Canadian government had plans for the West. John A. Macdonald harboured a vision of a country running “from sea to sea.” In addition to the prime minister’s grand plan, he was anxious to prevent the Americans from getting there first and laying claim to the Prairies. Macdonald moved quickly to prepare the groundwork for his expansion. In 1868, the Canadian government managed to get the British Parliament to authorize, for the following year, the transfer of the rights to Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the new Dominion. It was a bargain of historic proportions. Most of western Canada went to the new government for £300,000. It was also an alarming development for the Métis, as they had no part whatsoever in the consultations.

Recognizing that inclusion in a Canadian federation was all but inevitable, the Métis, under the leadership of Louis Riel, set up their own provisional government with the intent of negotiating the region’s terms of entry into Confederation. The Red River government had no legal status. Instead, it was a brash measure that Riel hoped would give him some leverage to negotiate the status of the new province. Riel was keen to preserve Métis land rights and French language rights, as well as to secure a commitment for a government-supported Roman Catholic education system, much like the one existing in Quebec. However, things soon went awry.

In 1869, Louis Riel’s men arrested Thomas Scott, along with forty-eight other members of the Canadian Party. When they were arrested, Scott and his fellow “Canadians” were readying themselves to storm Upper Fort Garry in an attempt to overthrow the provisional government. Riel actually sentenced Scott’s leader, Charles Boulton, to death, but then in an act of magnanimity promptly pardoned him. Things were different for the ill-starred Thomas Scott. He was a loutish, hot-tempered, and insufferable man, who proved to be a truculent and unco-operative prisoner. Riel, offended by Scott’s rude behaviour, and acting upon no authority but his own mulish instincts, sentenced Thomas Scott to death. On March 4, 1870, Scott was dragged in front of a firing squad and executed — the charges were for insubordinate and insulting behaviour.

Scott’s death caused a furor in Ontario. Newspapers were filled with lurid and often contradictory accounts of his murder. Sir John A. Macdonald, never one to forgo the opportunity afforded by a crisis, moved quickly. He dispatched troops to the Red River colony, and by May 12, his bill, the Manitoba Act, became law. The Manitoba Act created a new, fifth Canadian province. Relatively small, it was roughly one-eighteenth the size of the current Manitoba.* Four months later, after an exhausting march across Canada (a faster route, going by rail through the United States, was not an option), a column of British regulars and Canadian militia neared Red River. Warned of their approach, Riel fled into exile in the United States.

Riel’s efforts hadn’t been in vain. Anxious to keep the peace in the new province, Macdonald’s new Manitoba Act recognized Métis land rights, English- and French-language rights, as well as Protestant and Roman Catholic educational rights.

However, once Manitoba became a part of Canada, Métis land rights were largely ignored; and by the late 1880s, a movement to retract language and educational rights from French Manitobans would explode as a divisive and ugly national political crisis. By this time, many of the Métis had already left Manitoba. Following the diminishing herds of buffalo, many of the Métis moved away from the Red River to live in unsettled areas in Saskatchewan and Alberta, in what was then the North-West Territories.

Throughout the 1870s, immigration levels in the West were disappointing. Canada went into a steep recession in 1873 and the waves of settlers from abroad that the government hoped for didn’t materialize. Instead, most of the migrants to Manitoba in the 1870s came from Ontario. They joined smaller numbers of French-speaking Quebeckers who moved West for the promise of free land. Although there was some limited immigration of Icelanders, German Mennonites, and Central Europeans in this period, it would not be until well into the 1880s that the Prairies saw large-scale European settlement.

For what immigration there was to the West, the chief attraction was free land. For a registration fee of ten dollars, the Dominion Land Act of 1872 gave homesteaders 160 acres of land, with the condition that they had to grow their own crops and live on the land for three years. In theory it sounded like a simple proposition; in practice it was a test of character. Travelling to your new homestead was a daunting effort. Before the railways, if you were coming from overseas, the journey involved a long ocean voyage, almost always crammed below decks in steerage accommodation, followed by a trip by steamer and railway, usually through the United States, and then a long journey by oxcart or on foot to your homestead. At this point, the early settlers’ difficulties were just beginning.

The first few years of farming the land were not for the faint of heart. The Prairies had few building materials for house or barn construction, and most settlers had to face Prairie winters living in an uninsulated sod hut for weeks on end with temperatures regularly hovering at -30°C. The weather wasn’t the only problem. Growing and raising sufficient food to last through to the next harvest was no simple task. This was especially true for city-raised people who had little experience of farming. In those early years of Prairie settlement, before the railways, 40 percent of homesteaders had to make the heartbreaking decision to give up their dream and abandon their land within the first three years.2 Given the nature of the problems a settler had to overcome simply to survive for three years, this is an astonishing figure. Sixty percent of those who made it to their homestead managed to keep their 160 acres and went on to develop profitable farms. The high completion rate was a measure of the character of the times. It indicates an unshakeable tenacity and sense of purpose and commitment that is rarely ever required of modern Canadians.

In settling the West, migration was closely tied to railway development. Once railways were introduced to an area, things changed drastically for Prairie farmers. Goods of every conceivable nature could be brought in cheaply and efficiently. Hardware, building supplies, machine tools, and consumer goods of every possible description became available to Prairie pioneers after the introduction of railways.

It was not until December 1878, however, that the first western Canadian railway line was completed. The Pembina Branch, a line of track one hundred kilometres long, ran from St. Boniface to the American border and connected Manitoba to eastern Canada using American railways. The line was initially envisaged in the 1860s, but for political and financial reasons it was not built for nearly two decades. There was no direct Canadian link to the Winnipeg area until 1883.

Manitoba wasn’t entirely isolated before its first railway, though. Again, shrewd managers in the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1858 searching for ways of reducing logistical costs funded the development of American steamboat companies linking the Red River Colony with Minnesota. The result of these investments meant that steamboats on the Red River throughout the 1860s and ’70s rivalled in size and cargo capacity any of those in service on the Mississippi or Missouri rivers.

During the Confederation decades, Alberta and Saskatchewan were a part of the North-West Territories. They became provisional districts in 1882, and were eventually given provincial status in 1905.

At the outset of the era, the two provinces were populated primarily by First Nations tribal groups. Some historians have referred to the early and mid-century period as being a golden period for Plains First Nations. In hindsight, this is almost certainly wrong. The period was more likely a decades-long phase of transition between domestication of the horse and the catastrophic societal collapse that followed European settlement.

In the early decades of the eighteenth century, the first harbinger of European contact on the Canadian Prairies was the arrival of wild horses. Plains First Nations in Canada were quick to adapt to the horse’s arrival, and by the Confederation era, horses had been an integral part of their lifestyle for over a century.3 The horse changed First Nations societies in positive and negative ways. Mounted bison hunters were able to provide their bands a more abundant and reliable source of food. The horse’s domestication made tribes more mobile, allowing them to more readily follow the bison herds, and to own and move a greater number of goods. This new mobility also produced more conflict in the form of horse raids and inter-tribal war.4 But, most tellingly, the advent of the horse was also the early harbinger of a tidal wave of European migration, which for Plains First Nations was an historical disaster of near immeasurable proportions.

This momentous historical event arguably had a much more negative impact on Plains First Nations than other Canadian aboriginal peoples. Changes to their lifestyle were much more rapid and far-reaching than had been the case for First Nations of the Eastern woodlands or those west and north of Alberta. In the course of four short decades, the spread of disease, the elimination of the bison, and the physical marginalization of First Nations on the Prairies rapidly and irrevocably changed distinctive, functioning cultures into displaced, impoverished, and starving bands of refugees.

The first regular interaction Plains First Nations had with Europeans came in the eighteenth century when French fur traders expanded their operations as far west as the Rocky Mountains. Shortly thereafter, large-scale outbreaks of smallpox on the Prairies were recorded in the 1730s. Smallpox had already devastated Eastern tribes for decades, and as the fur trade pushed west, so too did this deadly pathogen. Records of these first plagues are anecdotal and no one knows for sure how many died, but we do know that it radically changed tribal demographics in many areas of the Prairies.

At around the same time, the arrival of the horse hastened the spread of the disease from a different direction. Smallpox epidemics, which had originated far to the south in the days of the Spanish conquistadores, steadily spread north, eventually arriving on the Canadian Prairies from the territories of more southerly equestrian tribes, such as the Dakotas, Pawnee, Comanche, and Shohsone. These more southerly tribes had already been carrying the infection, and horse trading, wars, and raids inexorably spread the disease to the Canadian Prairies. From this time on, the disease was rampant, recurrently springing up and decimating populations and changing the regional balance of power between tribal groups. Smallpox was not the only disease to produce incalculable damage and misery on Plains First Nations. Just as elsewhere, Europeans brought with them other virulent micro-organisms for which native populations had no resistance. Whooping cough, influenza, measles, scarlet fever, chicken pox, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and other diseases also spread rapidly over the same period, killing untold numbers of First Nations.5

Aboriginal societies on the Prairies suffered a second deadly blow as overhunting the bison across North America reduced their numbers from an estimated pre-1800 population of sixty million to near extinction levels by the mid-1880s. The decline of the bison herds was not a gradual process either. This kind of change followed a characteristic hockey stick curve, with a gradual upturn from 1800 to 1860, and, in Canada, an abrupt increase in the slaughter occurring in the 1870s and 1880s. As early as 1869, the Métis in Manitoba realized the bison herds were in decline, and many of them moved west from Manitoba to settle in Saskatchewan and Alberta, only to have the herds virtually disappear within fifteen years.

A Blackfoot family on the Prairies in the early 1880s. With the bison herds gone, Plains Indians found themselves hungry and displaced in a land that had previously provided them with all their needs.

The spread of cattle ranching in North America also infected bison with foreign diseases for which they also had little resistance: bovine tuberculosis, tick fever, brucellosis, and anthrax played a secondary role in destroying the bison herds. And if this was not enough, El Niño weather patterns in the 1870s caused years of severe droughts with enormous accompanying grass fires across the Prairies — an event that also hastened the collapse of the remaining herds. It almost seemed as if the environment itself was trying to speed the bison’s destruction.

Métis buffalo hunters employed in a Canadian survey party, Saskatchewan, 1871. Within five years, the bison and their way of life would be gone forever.

Decimated and weakened by disease, with their traditional food sources eliminated, the Plains First Nations were as devastated and tragic a displaced people as any in history. They were left with no place to go and no relief. The vast grasslands could provide no haven.

Native Americans on the plains had suffered the same diseases and lost their bison herds several years earlier. In addition, the U.S. government had, since the early 1860s, been waging a series of calamitous “Indian Wars,” wars that left aboriginal peoples not only destitute but utterly defeated. During that final horrendous decade, which saw the destruction of Canada’s Plains aboriginal society, criminal whisky traders, settlers, and railway and government officials would inflict even more misery and damage.

Prior to the advent of the railways, American fur traders and criminal frontiersmen established trading posts within the North-West Territories. Although some legitimate trade took place at many of these posts, so too did the unscrupulous practice of selling doubly distilled alcohol to vulnerable populations. Since the earliest days of New France, the fur trade had been associated with the ruinous custom of selling liquor to susceptible aboriginals. There were ineffective attempts to stop this as early as the eighteenth century. Quebec bishops threatened whisky traders with excommunication, and for nearly two hundred years there were other unsuccessful attempts to halt this practice. In the 1870s, in the North-West Territories, unprincipled whisky-traders — like drug dealers a century later — laced their addictive product with a variety of substances. Many frontier traders cut their cheap whisky with deadly substances: sulphuric acid, turpentine, gunpowder, strychnine, pesticides, tobacco, and hot peppers were all mixed into the liquor. In addition, traders in a dozen forts across the North-West Territories regularly cheated the natives of their furs and their horses, and many did a brisk trade in prostituting the starving wives and children of destitute tribes.6

One of the worst incidents of frontier lawlessness involved the 1873 killing in southern Saskatchewan of twenty-three natives by a group of drunken American and Canadian whisky traders who were searching for stolen horses. The incident became known as the Cypress Hills Massacre.

To curb growing lawlessness in the West, and to prevent a repetition of the Indian Wars that had taken place in the United States, the government created the North-West Mounted Police. Canada had few local police forces, and at the time, under the British North America Act, law enforcement was entirely a provincial matter. Policing had generally been the responsibility of the courts, but in times of civil emergency, the army was called out. The North-West Mounted Police were originally to be modelled after the Royal Irish Constabulary, but their training, discipline, uniforms, equipment, and organization more closely resembled that of a contemporary light cavalry regiment.

The new police force was spectacularly successful in bringing order to the North-West Territories. Their work was all the more remarkable, considering that they were operating over a vast territory, and, until 1885, had fewer than five hundred members. Operating in small detachments and using the principle of minimum force, the mounted police promptly cleared up the problem of whisky traders, and, in doing so, established close and respectful relations with First Nations.** Soon after, they became a key player in supervising and stage-managing the signing of what came to be known as the “Numbered Treaties.”

The government signed seven numbered treaties (1871–77) with Prairie First Nations during the Confederation decades. (There would eventually be eleven treaties, but four of these were signed after 1889.) Devised in Ottawa, the Numbered Treaties remain a contentious and, in the eyes of many, an ignominious issue in Canadian history — perhaps not so much for what they promised, but for the mendacious and cruel ways in which the government implemented them.

With the buffalo close to extinction, between 1876 and 1878, Canadian Indian agents, acting on instructions from the government in Ottawa, deliberately denied food to starving bands of First Nations. The policy of withholding food until the natives had moved onto designated reserves was an integral part of the enactment of the Numbered Treaties and was intended to do three things: to clear the Prairies of nomadic aboriginal bands, thereby allowing for European farm settlement; to ensure that the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway progressed unimpeded; and to once and for all destroy the aboriginal people’s migratory way of life as a first step in assimilating them into the larger Canadian population. It was a shameful and inexcusable chapter in Canadian history, one that, in the Prairies, inculcated a tradition and an enforced relationship of dependency and neglect.7 There are no accurate records as to how many people died of starvation as a result of this policy, but the policies of engineered famines and brutally inefficient administration meant that across the Prairies hundreds of First Nations people died of hunger and famine-induced diseases.

On the Prairies, the government promised First Nations reserve lands, hunting and fishing rights, an initial settlement followed by annual payments, as well as assistance with education, health care, and the purchase of agricultural machinery. The Numbered Treaties, along with The Indian Act (1876), became the defining legal instruments in determining the country’s ongoing relationship with its aboriginal peoples. In hindsight, it is clear the key expectation underlying the Numbered Treaties was that aboriginal peoples would, in the vocabulary of the period, become “civilized” or assimilated into white society.

Far from assimilating aboriginal Canadians, the Numbered Treaties and the Indian Act provided the historic basis for marginalizing, segregating, and impoverishing them. Although in fairness, despite the prevalent attitudes of the time being decidedly racist and chauvinistic, the impetus behind the Indian Act and the Numbered Treaties was not based upon racial hatred or contempt. As wrong and arrogant as it was, it is important to note that the underlying assumption was that the government thought it was doing the First Nations a huge service by setting up a system that would eventually see aboriginal peoples absorbed into the larger society. Given the establishment of segregated reserves and the prevailing attitudes toward race and social opportunity, this was a hopelessly unworkable contradiction.

Although it was never openly spelled out, reserves were not intended to be permanent homelands, because it was assumed that the aboriginal population would “civilize” and disappear as a cohesive ethnic group. What happened instead was that once First Nations were confined to remote reserves, a rapid and vicious process of institutional seclusion and marginalization began. Physically shunted beyond the margins of society, First Nations could not possibly be assimilated, or even fairly integrated, into the mainstream economy. Denied the vote and forcibly made wards of the state, aboriginal peoples were left with no political influence. Things were made worse as their affairs were overseen by a largely indifferent, tight-fisted, unresponsive, and incompetent government administration. Once First Nations were out of sight on reserves, they were effectively out of mind, and their problems were left to fester.

British Columbia’s aboriginal peoples fared only marginally better than the Plains First Nations. European contact resulted in very similar plagues of smallpox and other diseases. Smallpox epidemics erupted with generational regularity on the West Coast. Large-scale epidemics took place in 1770, 1801, 1836, 1853, and 1862. Again, it is impossible to know the precise numbers that died from the disease, but anecdotal records indicate that the disease was ruinous. In the 1862 epidemic alone, almost one-third of the First Nations population on the B.C. coast was believed to have died from the disease. The population of B.C.’s aboriginal peoples plunged from an estimated mid-eighteenth-century level of 180,000 to a late-nineteenth-century low of 35,000. This mortality rate is at least 20 percent higher than Europe’s worst localized plague estimates of the Black Death in the fourteenth century.8

While B.C.’s First Nations did not experience the immediate loss of their primary food source, as did the Plains peoples, they did suffer many of the same things as First Nations bands further east. Like them, they were all eventually subject to the Indian Act in 1876. As with all First Nations, assimilation was the stated official policy of the B.C. and Canadian governments. However, just as on the Prairies, the contradictory, segregationist regulations within the Indian Act made assimilation an impossibility. First Nations were compelled to live on reserves, arbitrary restrictions were placed on their movement off reserve, and they were denied the vote. On the other hand, harsh measures were vigorously imposed to extinguish existing aboriginal culture. The Indian Act forbade their right to wear traditional clothing, and it outlawed specific traditional rituals and practices, such as potlach.

Potlatch was a centuries-old ritual of the Northwest First Nations and some interior tribes. It served as a time-tested means of redistributing wealth through gift giving, appointing band leaders, confirming in public any changes in status such as marriages, birth, death, and coming of age, and it also had a practical social purpose in the maintenance of relations between tribes. In 1884, the Indian Act banned the ceremony on the grounds that it was profligate, irresponsible, and reckless behaviour that undermined a band’s economic vitality. Banning the ritual had far-reaching and negative social implications.

In addition to this, indigenous community leadership was further undermined as the Indian Act appointed Indian Agents who exercised administrative power on the reserve and became the band’s sole official intermediary with the government. In yet another inconsistent measure that would prevent economic and social integration, Indian agents could and did arbitrarily choose to restrict the external sale of any agricultural produce or livestock raised by the band.

In British Columbia, attempts to destroy aboriginal culture were probably the result of high-handed, instinctive, and deeply ingrained assumptions of cultural superiority rather than the result of any specific attempt to clear the land for white settlement, as happened on the Prairies. Aboriginal settlements were generally remote, and by the time of the Confederation decades, aboriginal population densities were so low that they posed no threat or obstacle to migration and settlement.

West Coast First Nations attend a ceremony marking British Columbia’s entry into Confederation.

At the outset of the Confederation period, the only settlement of any size in British Columbia was the tiny outpost of Victoria. Britain was keen to lay claim to Vancouver Island, and so established an isolated Hudson’s Bay Company trading post on the island in 1843. Previously, the Hudson’s Bay Company had run most of its operations from Fort Vancouver, which was then situated on the Columbia River in what is now Oregon.

As rich as British Columbia was in natural resources, it developed late as a colony. This was not for lack of interest, but because it was commercially accessible only by the long ocean routes around either the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. The threat of American expansion westward once again aroused British and Canadian interest in securing the West coast as part of the British Empire.

Britain, sensing America’s growing strength and aggressive temperament, was anxious to resolve by negotiation its ongoing boundary disputes with the United States. In June of 1846 the Oregon Treaty redefined the disputed boundaries between Oregon and New Caledonia, as the B.C. mainland was then known. The timing of the treaty was indicative of the new-found respect Britain had for an increasingly powerful United States. Just six weeks before the treaty’s finalization, a bellicose America had declared war on Mexico. By the end of that war, America had added California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico to its territory.

While British Columbia was by mid-century firmly and lawfully British, the only non-aboriginal settlements on the West Coast were the village of Victoria and a string of scattered fur trading posts. In 1858 that began to change as a result of the discovery of gold on the British Columbia mainland. Victoria and Vancouver Island went through a sudden metamorphosis. The village changed from being a trading post and insignificant maritime coaling station to being the capital of a colony in its own right, as well as the main commercial supply centre for gold miners headed to the gold fields on the Fraser River. Just as California had boomed between 1848 and 1855, Victoria and mainland British Columbia expanded at a feverish pace. Within the space of weeks, Victoria grew from three hundred people to over five thousand. Unable to control the flood of migrants to the lower mainland, Governor James Douglas recommended that the area be declared immediately open for settlement and the land sold for twenty shillings an acre.

The initial gold rush of 1858 petered out, but it was followed by another in the interior Cariboo region in 1860. This one created a boomtown of wooden huts, plank sidewalks, and shanties called Barkerville. It is estimated that in the early 1860s, Barkerville had a population of ten thousand people, making it the largest town in western Canada at that time. As in all gold rushes, the initial exhilaration and wild hopes were followed by hard reality.

Many eventually left Vancouver Island and the mainland, but that first spark of activity touched off a string of changes that would turn British Columbia into Canada’s sixth province. Britain declared mainland British Columbia as a separate Crown colony in 1858. They were made one colony in 1866.

British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871. The conventional wisdom is that the delegates haggling over the terms of entry demanded that Canada had to build a railway connecting the Prairies to the Pacific coast. In fact, what the B.C. delegation asked for was far less dramatic. They simply wanted a wagon road. John A. Macdonald was the one who upped the ante and made the offer more attractive by proposing a railway instead.9

Like many of Macdonald’s ideas, it was a shrewd move and a bold gamble. The Royal Engineers had built the Cariboo Road through the B.C. interior during the second gold rush. It was a tricky piece of engineering and was probably what focused the provincial delegates on the idea of building a second road. Macdonald likely realized that putting a railway through the mountains would take just as much work, and would have to be in place in any event if the province was to be commercially connected to the rest of the country on a year-round basis. The deal was made; Canada took on B.C.’s massive debt load and promised to link the coast with a transcontinental railway. But it was a much more difficult proposition than anyone anticipated. British Columbia didn’t get its railway link to the coast for another fifteen years.

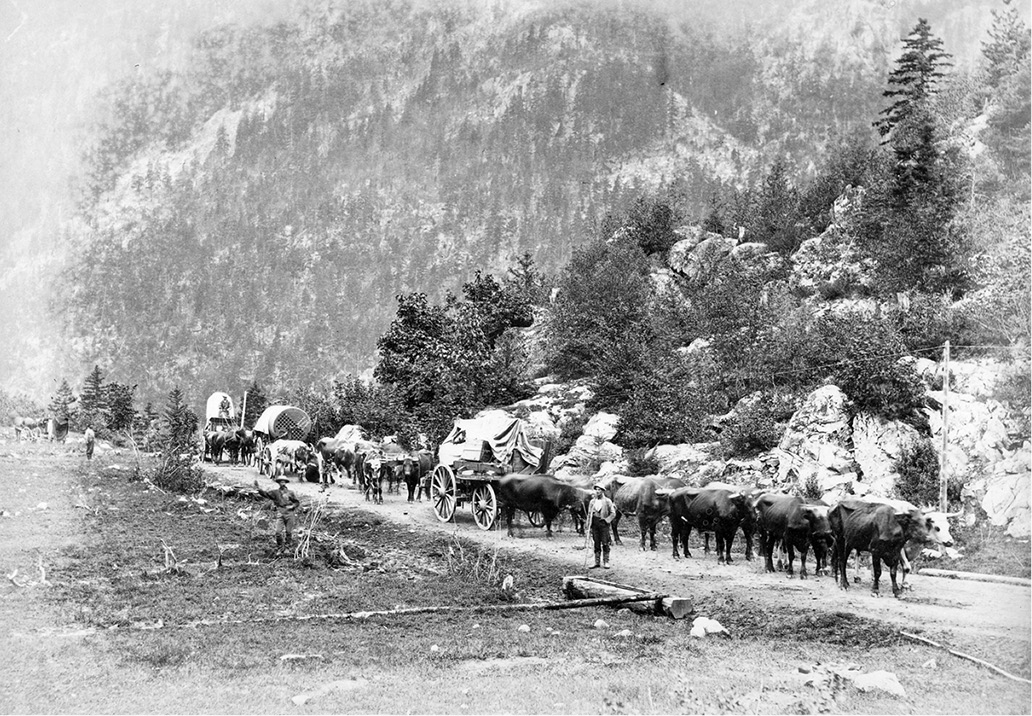

A wagon train in B.C.’s Cariboo Mountains, 1870s.

By the end of the Confederation decades, British Columbia’s territory was half the size it is today. At the end of the 1870s, Vancouver was little more than a hamlet, with a sawmill, and a few shops, taverns, and houses perched around the Burrard Inlet. It was another six years before it was incorporated as a city. By 1880, the entire province was still not much more than an embryonic hinterland, and only had a population of less than fifty thousand people. That would all change once Macdonald’s railway was completed, at which point the province began to industrialize and each decade averaged 70 percent population growth for the next forty years.

Canada’s High North has been inhabited by the Inuit, a people who migrated out of what is now Alaska almost 1,200 years ago. The Inuit in turn were descendants of the Thule people who migrated from north-eastern Siberia over 4,000 years ago. As a cohesive aboriginal culture and people, the Inuit have the most extensive geographic range of all the world’s traditional peoples, with communities stretching across Greenland, northern Canada, Alaska, and eastern Siberia.

Throughout the nineteenth century, they lived a traditional semi-nomadic lifestyle on a landscape that has changed very little since then: vast expanses of barren grounds and tundra populated with scattered herds of caribou and muskox as well as small populations of wolves, fox, arctic hare, and lemmings. The Arctic islands and coastal areas were home to seals and walrus packs as well as seventeen species of whales that migrated in the channels.

Inuit hunters cleaning a walrus after a hunt at the edge of the ice pack.

In winter and summer in the Canadian Arctic, the Inuit survived in extended family groups: hunting on the tundra in summer and fishing and sealing on frozen coastal areas in the winter. Their laws and traditions were passed down orally, and they followed a traditional animistic belief system of reverence for all things both living and inanimate.

Canada’s High North saw the beginnings of change during the Confederation era. In the mid-nineteenth century there was intermittent contact between the Inuit and those of European descent. Most of the interactions between the two groups were between small, isolated Inuit communities and American whalers, hunting for narwhales, belugas, and oil-rich bowhead whales during the season’s short, ice-free window. Periodically, there were a few encounters between explorers and Inuit. For the most part, all these contacts were amicable; and some, particularly those meetings with whalers, resulted in small-scale annual trading exchanges. Through these meetings, the Inuit were gradually introduced to firearms, cloth, metal, tools, cooking utensils, Western musical instruments, as well as alcohol and tobacco.

Although there was little overt conflict, the Inuit suffered terribly from these first encounters. Accurate statistics are difficult to come by, but the Inuit are believed to have suffered at least as much as the First Nations did from diseases introduced by Europeans. Some estimates place nineteenth-century Inuit deaths from disease as high as 90 percent.10

Their lifestyle was changed forever by the alien-looking men, who spoke bizarre sounding languages and arrived in strangely shaped ships. Perhaps the most famous of the alien-looking men of the Confederation era was Sir John Franklin, a Royal Navy officer, Trafalgar veteran, and an experienced, although obdurate, explorer. Franklin, who had been on three previous exploratory expeditions, was no stranger to the North. A previous overland expedition that he led to explore the Arctic coastline ended in near disaster. Franklin refused to listen to his aboriginal guides and trappers and mounted his expedition without making use of local sleighs or suitable clothing. Instead, his expedition wore British uniforms and brought with them mess china, silver, and table linens. Over the course of almost three years, he lost half of his men. The mission was plagued by mutiny, starvation, murder, and cannibalism. The expedition did have two redeeming outcomes: it furnished a good example of how not to run a northern expedition; and Franklin’s maps and charts provided a much-improved appreciation of Canada’s Arctic coastal areas.

Back in England, Franklin was hailed as a hero. In 1845, he was given command of two ships, the Erebus and the Terror, and tasked to find the Northwest Passage. The ships were provisioned for three years, and equipped with the latest scientific research instruments. Underestimating the distances involved, however, Franklin’s vessels became trapped in the ice near King William Island. The crews struck out on foot and tried to make their way overland to safety, when they realized their ships would likely be crushed in the shifting ice.

Uncovering the fate of the Franklin expedition became a cause célèbre in Victorian society. A total of twenty-six missions were sent out in search of the lost Franklin Expedition, but little was heard of them — except for a three-man gravesite and Inuit reports of an abandoned ice-bound ship and starving sailors trying to seek safety. A further three graves were discovered on Beechey Island in the 1980s. Thirty-four years later, Canadian Coast Guard divers found the wreck of the Erebus lying upright in eleven metres of water on the sea bed of Queen Maud Gulf. The Terror was discovered two years later in 2016, well to the south, submerged, but in good condition.

Franklin’s voyage was certainly the most famous of the Arctic expeditions during the Confederation era, but it was far from being the only one. There were many other exploratory missions to Canada’s North launched by British, American, Austro-Hungarian, Dutch, German, and Norwegian explorers, but, significantly, no Canadians tried to explore the region. Nonetheless, despite its lack of presence in the Arctic, Canada extended its claims of sovereignty over its current Arctic borders in 1880.

* Manitoba’s size would increase in 1886 and again in 1912.

** The legacy of the North-West Mounted Police had other unintended offshoots. Frequently, their outposts developed into modern Canadian cities, as in the case of Calgary. The detachment’s original egocentric and unpopular commander, a Captain Éphrem Brisebois, named the station “Fort Brisebois.” The day Brisebois was posted out, the troops renamed their base “Fort Calgary,” after Calgary Bay on the Isle of Mull in Scotland. The new name stuck.