10Choice of post-1300 Norwegian data

It is customary to set the beginning of the MLN-era to 1350 (Indrebø 2001:148) or to around 1370 (Torp & Vikør (1993:116), Mørck (2011:34)). The Black Death in 1350 decimated the country’s intelligentsia (Indrebø 2001:202; Haugen 1976:286). By 1370–80, most of the scribes who received their education prior to the Black Death were dead and had been replaced by a generation of scribes with “inadequate training” (Haugen 1976:286); this is what has motivated the choice of 1370 as the starting point for MLN. In more recent research, this traditional account has been questioned; see e.g. Hagland (2005). I will still stick with the traditional delineation and set the beginning of the MLN period to 1350.

However, I have also chosen to include in Part 2 diplomas from 1300–1350, i.e. from a 50-year period before the start of MLN. Above all, this is because Part 2 of this book has a diachronic perspective; I wanted to avoid too long a timespan between the ON and the MLN data. It is true that this creates a slight overlap with some of the ON data (the Borgarting and Eidsivating codes), but I see this as a much smaller problem than the alternative, which would be to leave out the linguistically valuable 1300–50 diploma data. In this regard, it needs to be stressed that MLN syntax is seriously underresearched compared to phonology and morphology101. In his extensive overview of the changes in the Norwegian language in MLN, Indrebø (2001) devotes 13 pages to phonological changes, 20 to morphological changes, and only 3 to syntactic ones. While most of the morphological and phonological changes might have taken place after 1350, it cannot be ruled out that important changes in syntax, and more specifically in the RC construction, happened before that time.

I will refer to data from inside the MLN-period (1350–1525) as my MLN data. If it is necessary also to also include data from 1300–1350, I will speak of the post-1300 data (comprising all data from after 1300). The MLN data have been taken from the Diplomatarium Norvegicum, a 22-volume collection of legal documents of various kinds, including court rulings, exchanges of property, testaments, contracts etc. They constitute the only source available for the study of MLN.

The document from which each example is taken is given in brackets after the example, with the volume of Diplomatarium Norvegicum followed by the number of the document and the year of issue. So, for example, DN 5.723–1444 means the example is found in volume 5, diploma number 723, dated 1444. I have looked at the first eight volumes.

The end of MLN is commonly set to around 1525 (Mørck 2011:32); by that time, the vast majority of official documents in Norway were written in some kind of Danish. I would like to stress that I do not use the terms ‘Norwegian’, ‘Swedish’ and ‘Danish’ to refer to any established norms. There were no established standards for the Scandinavian languages yet. There might have been certain unwritten rules or conventions, but this is a discussion I wish to stay aloof from. However, MLN scribes might be influenced by Danish or Swedish usage (or what they perceived as such). Whenever I use the terms ‘Swedish’, ‘Danish’ and ‘Norwegian’ in a 15th century-context, read ‘language usage in Sweden, Denmark and Norway’.

The topic of this chapter is the development of the MLN RC. This means that I will not discuss the many other issues which the data might provide insight into, like dialectal or sociolectal variation; stylistics; the existence or non-existence of a written norm; the question of ‘literacy’ (Hagland 2005); political developments, etc. The factors above are of interest only insofar as they can shed light on the main question: The development of the RC construction.

Certain factors should be taken into account when selecting data:

–influence from Swedish (in particular from 1425 to 1450) and Danish (in particular after 1450) might render a text less useful, since a given phenomenon attested in the data might reflect influence from usage in Sweden or Denmark rather than an authentic change in Norwegian. However, as Indrebø (2001:175f) sums it up, Swedish influence – while leaving certain traces (usually quite recognizable, like the personal pronouns wi, i and jak) – rarely extended to the point where the text could no longer be said to be Norwegian. The same goes for Danish until around 1500.

By the early 1500s, Danish has taken over as the main language of administration. I have generally decided not to investigate texts written in Danish, but, given that beggars can’t be choosers, I have made certain exceptions, if the text in question exhibits features of a clear Norwegian nature (e.g. certain inflectional endings, diphtongs etc.).

On the other hand: Danish/Swedish influence might also exert an influence on spoken Norwegian and not just on the written conventions of Norwegian scribes (see below). Lindblad (1943) points out that in Late Old Swedish, the relative complementizer sem already in Old Swedish showed a tendency to be associated with the subject function, whereas in Old Norwegian there was no such correlation (er/sem was obligatory regardless of syntactic function). In MNO (as well as Modern Swedish) som is obligatorily inserted whenever the subject is relativized. This poses an interesting question for the diachronic scholar: Did Norwegian acquire the MNO rule of som-in-sertion through contact with Swedish, or was it merely a case of a parallel development in the two languages which happened to start earlier in Swedish?

It is therefore important to distinguish Danish/Swedish influence that only affects the language in a given document from Danish/Swedish influence that represents a genuine change in Norwegian induced by language contact. It can be added here that dealing with syntax makes the interference problem less of an issue; Mørck (2011:42) argues that the syntactic differences between Danish and Norwegian are probably much less significant than the morphological or phonological ones.

–Dialectal variation is probably of little relevance to a study of diachronic RCs in Norwegian. For example, there is little or no variation with regard to som-insertion in RCs or RC word order102. It is of course not inconceivable that Norwegian dialects at one point varied with respect to the RC-construction, but that this variation was later cancelled out due to language contact or standardisation. However, according to Mørck (2011:36), no syntactic differences have been discovered yet between dialects in ON or Middle Norwegian. (A dialect focus would any way require a much more philologically thorough approach, since scribes were known to move from place to place, so that the place of origin of a given text is not always a good indicator of the dialect reflected in the document.)

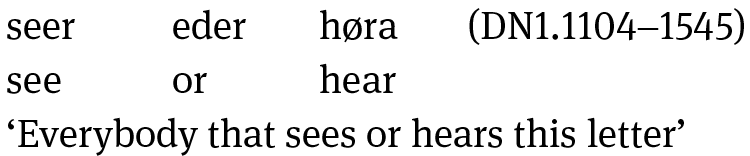

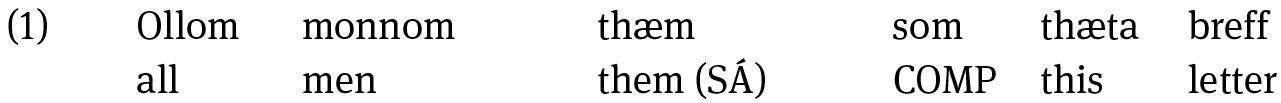

–As pointed out by Indrebø (2001:242), most diplomas have a standardized structure with extensive use of formulaic language. This makes them less interesting from a linguistic point of view. This means that I have had to look for diplomas with more narrative content. The formulas retain archaic morphology and syntax no longer found in non-formulaic language. So for example the introductory formula clings on to its postnominal demonstrative, even at a diachronic stage where demonstratives practically always occur prenominally:

To avoid relying too much on formulaic language, I have deliberately been looking for texts that are rich in narrative content. Provsbrev – legal documents dealing with criminal matters, especially manslaughter – are usually assumed to feature longer narrative sequences than other types of documents (Hagland 2005:44), so they constitute an important part of the data.

The Early MNO period is also of interest, but data are scarce, as Norwegian ceased to be used as an official language. What we have for the Early MNO period are certain prose texts (essays, letters to newspapers) as well as some fiction (mainly poems and festive songs). Unlike the diplomas, the Early MNO texts have no connection whatsoever with the ON tradition of writing (Mørck 2013:643). Den fyrste morgonblånen represents the largest collection of such texts; I det meest upolerede Bondesprog a smaller one (restricted to the Trøndelag region). These texts are hardly ideal for linguistic research as they often mix Danish and Norwegian dialects and are often not even written by a speaker native to the local dialect. They also leave a big gap between the last useful MLN texts (ca. 1525) and the first Early MNO text (a Bible translation from 1698). Be that as it may, for want of better material I have consulted these data if they can say something about the post-MLN development of the RC construction.