12

Role Model and Icon

British photographer Iain McKell’s eloquent black and white portrait of Youssou N’Dour wearing Ray-Ban sunglasses and headphones along with a traditional Senegalese straw sun hat and embroidered boubou perfectly captures Youssou’s ancient musical heritage as well as his own style of modern pop music. The celebrated photographer of celebrities like Brad Pitt, will.i.am, Gilbert & George, Grayson Perry and Vivienne Westwood took the publicity shot in the mid-1980s during a photo shoot in a warehouse studio in Shoreditch in east London. Following several changes of costume and many different poses, McKell made this one and knew immediately he had the image he was seeking.

52. Iain McKell’s portrait of Youssou.

One day in the late 1980s Youssou introduced me to a man he described as his biggest fan. Issa Samb, alias Joe Ouakam, artist, philosopher and art critic, whose Lébou family once owned large swathes of land around the village of Ouakam, was walking his dog along the seafront near Youssou’s house when he stopped to speak with us. I subsequently met Issa on many occasions, often in his Laboratoire Agit Art on the Rue Jules Ferry in central Dakar. On one of these occasions, he defined Youssou’s place in modern Senegalese life and art thus:

Youssou speaks for at least three generations. He comes from Medina, a place apart with its own history and habits, a place stamped with the mark of independence where boys turn up their coat collars and walk defiantly and with attitude. Youssou is an innovator who has always surprised us and will continue to surprise us. He is capable of working with any musician on the planet. That deep emotion, that sensitivity, that humanity, that pragmatism which is never arrogant can only come from an exceptional being, a person with what we call genius. He seems continuously to renew his inspiration, making gigantic efforts to advance his music beyond the borders of Wolof culture and out onto the international stage.

.jpg)

53. Joe Ouakam.

Senegalese architect and film-maker Nicholas Cissé thinks there is a strange inevitability about Youssou’s success, and that this relates to his griot/gawlo heritage. He told me in Dakar in 2006:

There is no such thing as a minor griot. All griots have inherited the same gifts of singing, playing instruments or talking. Their feats of memory are remarkable; the power of their words awesome, their proverbs ring true like Shakespearean couplets. Each generation sings and speaks and plays and the words accumulate until the day when a plethora of words falls on one griot who receives the ultimate gift and becomes a megastar called Youssou N’Dour.

Retired linguist and translator Souleymane Diakhaté told me that he believes Youssou is one of God’s chosen ones, chosen to show other Senegalese musicians that it is possible to succeed and even to become a superstar. Good looks, charisma and a natural reserve have all contributed to the mystique surrounding Youssou, especially at the outset of his career. Growing notoriety forced him to retreat from the usual routines of everyday life in order to escape being mobbed by crowds. Ironically, he was freer to live a ‘normal life’ during his visits to London, New York or Paris than in his home city.

In 1992, an assassination attempt targeting Youssou recalled a similar attack on Bob Marley in Jamaica in December 1976 or the cruel killing of John Lennon in New York in December 1980. Since Youssou was on tour in Germany he escaped, but the world’s press carried the report that a man intending to stab the Senegalese pop star rushed into the singer’s Dakar office and seriously wounded one of his friends, a young man nicknamed ‘You 2’ because of his physical resemblance to Youssou. Then the perpetrator turned himself in to the police, saying he had just killed Youssou N’Dour. The victim was a young man named Abdou Ndiaye, who subsequently died of his injuries.

Thanks to his work ethic, patience, pragmatism and an eye for an opportunity, Youssou understood what it took to advance his career and secure his place on the international music scene. Promotional tours involved journeys on planes and trains and nights in hotel rooms followed by hour upon hour of interviews and photo shoots. Gradually, Youssou became a role model for a new generation of Senegalese artists. His serious, clean-living image broke the mould and rendered the music profession, once frowned upon as the preserve of drunkards and womanisers, respectable.

Like many performers, when Youssou is onstage, the one place he feels really free, he transcends his natural timidity and the instant response of his audience gives him an extraordinary power. Clearly he has that indefinable attribute we call ‘star quality’, and this epithet, ‘star’, has followed him from the outset of his career: Star Band, Étoile de Dakar and finally Super Étoile de Dakar. The core group of musicians who made up his backing group and recorded his albums remained together for more than thirty years.

The enigma that is Youssou N’Dour

Youssou is notoriously inscrutable. ‘I must have met him at least 10 times,’ British writer Mark Hudson noted in 2004,

and while he is always friendly, even jovial in a blokeish high-fiving way … he tends to be infuriatingly circumspect and diplomatic. At times I’ve felt that I’ve pushed ever deeper into what makes him tick; at others I’ve wondered whether I’ve recorded one sentence that reveals who he really is.1

Hudson also suggested that Youssou must have known from the beginning he was not an ordinary person. As mentioned in the Preface, it is true that in the early years his Senegalese fans would shout that he was more than a human being and that everyone wanted to touch the hem of his coat.

Senegalese journalist Massamba Mbaye offered me this perceptive comment about Youssou:

Despite a meticulous perusal of this peerless artist’s work, there is still something profoundly unfathomable in it. Look at his eyes. Youssou does not look at the present, he looks into the future. But the mirror which reflects his regard has been polished down the centuries. He belongs with the inventors, those who know how to turn the pages of time ever so carefully, for each page is precious.

Mbaye’s press colleague Khalil Gueye told me, simply: ‘No one is perfect, especially an artist who creates perfect art.’ And renowned sculptor Ousmane Sow commented that

Youssou endures because he is clever. He deftly manages every project, never taking on too much and always keeping his feet on the ground. He has never allowed his fame to go to his head, for he is exactly the same person he always was, and that is a mark of his intelligence.

Interviewed for the Senegalese newspaper Le Quotidien, Youssou admitted that the one person who knows him best is his mother. ‘My mother and I are very close,’ he told the newspaper.

She knows everything about me, and like all mothers she lives only for me. She knows what I am capable of and what I will never do. She is also a partner who makes things go smoothly for me. As for my father, he is a very rigorous and straight man and I am afraid of him even today.2

When asked in the same interview, ‘Who is Youssou N’Dour?’ Youssou had this to say:

I really find it difficult to answer that, but each person has a mission. My mission is to show that it is possible to succeed. I believe sincerely that whether one is born in New York, in Singapore or Dakar, one can be successful and give hope to others. I take care, as we all must, to show our young people that they should have principles. They too can aim high, and they too can be fulfilled. I find it difficult to talk about myself because I forget easily, and that is maybe a good thing. My father used to say that to make progress in life one should not focus on the past. So I go forward. I am lucky to make my living through music, which is my passion.3

I have immense admiration for Youssou as a singer and musician. As a person he is extraordinarily even-tempered – I have only once seen him angry, and that was when a tour manager made an unfortunate mistake. He is an extremely private person who shows little emotion, though he demonstrates great tenderness towards his children. In the way of the griots he reads other people very well; a shrewd negotiator, he conducts his business affairs on the basis of give and take, his motto being only to give when you can get something in return. His attachment to his country, his hopes for the future of his people and for Africa in general are genuine and are reflected in his own achievements.

Self-made millionaire

It quickly became clear that Youssou had the rare ability to combine artistry with a head for business. Latyr Diouf, his former manager in Dakar, says he was always impressed by Youssou’s belief in himself and with his capacity for hard work. In his view, every year from 1981 onwards – when Youssou launched his solo career with the Super Étoile de Dakar – was an epic one for multiple reasons, and each year was more glorious than its predecessor.

In March 2016, the website Buzz Senegal published a list of the five wealthiest men in Senegal. Youssou’s name was fifth on the list, with a supposed fortune of 95 billion West African CFA francs (around £96 million).4 In May 2014, the website Constative stated that Youssou was the richest African artist, with a net worth of $135 million.5 This is unsurprising when you consider what he has achieved over the years. A man of ideas and an innovator, he built a recording studio in Dakar before establishing the record label Jololi and a music promotion company, Xippi Inc. Through his various enterprises – the Thiossane Club, the newspapers L’Observateur and La Sentinelle, Radio TFM, the Youssou N’Dour Foundation and the television company Futurs Médias – he employs more than 800 people.

When he initiated the Joko (‘link/connection’ in Wolof) programme to provide internet access in villages across Senegal, Youssou was optimistic about the internet’s potential to help African economies leapfrog industrialisation and aspire to more equitable partnerships in the world economy. In February 2008, with support from the Italian company Benetton, Youssou launched a microcredit scheme, Birima, to support small business enterprises in Senegal, declaring, ‘Africa doesn’t want charity, it wants repayable subsidised loans.’6

In the autumn of 2009, just before Youssou’s fiftieth birthday, I met him backstage at the O2 Arena in London and asked him what his ideal birthday present would be. After a brief reminiscence about Phil Collins’s fiftieth birthday party where, after the guests had assembled, a curtain was opened to reveal Peter Gabriel and the other members of Genesis seated at their instruments ready for Phil to join them, Youssou said without hesitation that his best birthday present would be the unveiling of his new TV station in Dakar.

On the basis of a government promise to grant him a licence for an independent TV station, Youssou bought the necessary equipment, but suddenly the licence was refused and no explanation given. So he set about gaining 10,000 signatures – mostly from his fan base – in order to back his bid, and a licence was finally granted to Télé Futurs Médias. The station, TFM, went on air in May 2010.

Some people have described Youssou as being ruthless in his business affairs, but my friend Souleymane Diakhaté’s view is that Youssou has needed to be rigorous and forceful in order to succeed in an unstructured and informal economy.

He has also been accused in some quarters of nepotism. However, given that Senegalese tradition expects the taaw (eldest son) to set a good example so that the rest of the family will succeed, it is hardly surprising that as the eldest son Youssou has made use of his family’s talents to support his business interests. Far from seeing it as nepotism, he is proud that his brothers and sisters – and now his son Birane – are working for his media and music companies. Youssou’s sister, Ngoné N’Dour, studied sound engineering in London and became chief executive of Xippi Inc., with her brother Bouba N’Dour as artistic director and her sister Marie N’Dour as the company’s international representative in France. With her brothers Prince Ndiaga N’Dour and Ibrahima N’Dour, she formed Prince Arts, a production company for the promotion of local artists through events, films and recordings. In 2016, Ngoné was elected PCA of the Senegalese copyright and related rights society (SODAV). Prince Ndiaga is chief technician at Télé Futurs Medias, where Youssou’s son Birane is associate chief executive. Ibrahima also played keyboards on Youssou’s album Rokku mi Rokka and really came into his own as arranger on the 2016 album Africa Rekk. He told me,

54. Some of Youssou N’Dour’s siblings as children.

I listen to all kinds of music. For example, I discovered a style which resembles mbalax but which is simpler and instantly appealing. It is the bachata from Puerto Rico, and I introduced this rhythm along with others in Africa Rekk. I also like to keep abreast of new talent.

Youssou’s sister Aby N’Dour, a singer and designer, has set up her own fashion house in Dakar, and in August 2018 she released a new single titled ‘Ni Lay Sante’ (‘This Is To Say Thank You’).

Despite his meteoric rise to superstardom, Youssou has also been pleased to endorse the careers of emerging singers and musicians, especially in Senegal, where Cheikh Lô, Viviane, Pape and Cheikh, Carlou D and Daara J were among his protégés.

When I left the BBC in 1996, Youssou promptly invited me to work with him, an invitation I was delighted to accept. And so I headed to Dakar for a prolonged stay. Planes flying south to the city hug the Senegalese coastline, providing passengers with a bird’s-eye view of fishing villages and the Lac Rose, its pink-tinged mineral waters clearly visible from the air. On its final approach, the aircraft circled over Gorée Island then glided down over the rooftops of Mermoz and Ouakam to land at Léopold Sédar Senghor airport.

My job title was International Liaison Manager for Youssou, his record label, Jololi, and his commercial recording studio. I lived in a room at the top of Youssou’s three-storey house in Almadies, which was designed by architect Nicholas Cissé to resemble a West African kora, and I had my office on the second floor. Youssou and his family lived in the same building and he himself was closely involved in running the music business. When, in high summer, there were frequent power cuts, we would sit outside in the courtyard to get some air and Youssou’s wife, Manacoro ‘Mami’ Camara, who has a keen sense of humour, would entertain us all with witty stories from her days as a bank official while some of Youssou’s close friends regaled us with tales of their youth. On these occasions, the congenial atmosphere reminded me so much of an Irish ceili (house party) that I felt very much at home.

Nowadays Youssou no longer lives in the house at Almadies; the entire complex has become the busy headquarters of Télé Futurs Médias, a site bustling with eager young journalists, technicians and television presenters.

Youssou N’Dour, Minister of Culture, Tourism and Leisure

When upon his election in 2012 President Macky Sall announced the appointment of twenty-five new ministers, half the number that had served in the previous government, Youssou was named Minister of Culture and Tourism. Sceptics wondered if he could succeed in a post for which he had no formal training. I remembered what Pape Dieng, former drummer with the Super Étoile had once said, ‘Youssou always has an idea and he has always relished a challenge,’ but questions remained: would his quick intelligence, pragmatism, contacts and experience of the world allow him to initiate and carry ideas through? Even though he is no bureaucrat, would his entrepreneurial skills and his flair help him to open up the ministry, encourage collaboration with the private sector and mobilise other people’s talents?

In one of his first speeches, Youssou defined the importance of his mission, stating that Senegal may not yet have mineral resources or petrol, but that it has cultural and intellectual riches instead.

Then early in 2013, Youssou was replaced as Minister of Culture by Abdoul Aziz Mbaye but retained the portfolio for Tourism and Leisure. He claimed that his worldwide reputation would be useful in his new role, but an editorial in the newspaper Le Pays au Quotidien was moved to comment somewhat caustically:

Is it enough to have sat at Bono’s table for the perception of Senegal as a tourist destination to change? Is it sufficient to have attended the G8 as a spokesperson for Africa to imagine that everything he touches will turn to gold? Tourism will not flourish through the aura of the man charged with reviving it, for it is an eminently economic sector … Tour operators may adore You the artist but You the Minister must find the means to convince them that Senegal as a destination is not only attractive but competitive in price too.7

The same journalist questioned whether Youssou himself felt comfortable in his ministerial role and averred that as a political figure, Youssou would be a target for more criticism than he ever faced as a musician or media mogul:

If the Senegalese people discover that the present government’s policy of ‘Yonou Yokkouté’ [The Path to Prosperity] changes their lives for the better, Youssou’s political odyssey could be described as glorious. On the other hand, he could be written off as an inglorious politician involved in a misadventure which interrupted his legendary career. He may then take comfort in listening again to his back catalogue! Legends do not die, but they can lose their way.8

Return to the stage

In February 2013 it was announced that Youssou had been given permission by the president and the prime minister to resume his musical activities while retaining a ministerial post, this time as special adviser to the president. Youssou explained how that worked:

I carry out missions, I take part in strategy meetings, I suggest ideas, I alert the president and advise him on all issues. This work demands less time which allows me to return to my music. However, my political life remains important.9

Back on tour in Europe he revealed some disillusionment with the processes of government when he told Mark Hudson, ‘When you’re outside politics, it’s very easy to say, “Why didn’t they think of that?” or “Why are they so slow?” But when you get inside, you realise how complicated the processes are.’10

In the interim, the rift which had developed between Youssou and his long-time musicians Habib Faye and Jimi Mbaye, who were dismayed at the manner in which he had left his superstar band in the lurch while pursuing his political aims, had now left an obvious gap. Into the breach stepped the young guitarist Moustapha Gaye, while Cameroonian bass player Christian Obam Edjo’o replaced Habib Faye.

On 12 October 2012, the morning of the eleventh Grand Bal at Bercy, Youssou was the guest of Catherine Ceylac on her France 2 TV show Thé ou Café. The elegantly directed studio programme reviewed the high points of his career before showing footage of recent rehearsals at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, an established classical music venue that is now as familiar to Youssou as the Royal Albert Hall in London or the Opéra Garnier in Paris. Despite the continued absence of Jimi and Habib, Youssou assured his interviewer that he had all the human resources he needed. Yet, in what seemed a veiled reference to his former stalwart colleagues, he alluded to his discomfort when musicians take up too much space. Given the long term cohesion of his group and the considerable contribution the Super Étoile musicians made to Youssou’s recordings and stage shows down the years, the implied breach of confidence was clearly painful, as painful as any separation between people who have been close for a long time. However, the story had a happy ending: in November 2017, all the Super Étoile musicians, including Habib Faye and Jimi Mbaye, performed on stage with Youssou at that year’s Grand Bal.

.jpg)

55. Youssou with Barack Obama.

Always keen to project a positive image of Africa, Youssou invited Ms Ceylac to visit Senegal to experience the welcome of its legendary teranga, its vivid colours, creativity and exuberance. Joined by Senegalese singer Julia Sarr, he finished the live show by singing ‘Africa Dream Again’: ‘Wake up, stand up, Africa … dream again … smile again.’

In July 2014, during a speech at the US–Africa Summit in Washington, President Barack Obama toasted the New Africa, inspired, he said, by a song of that name that he had first heard in Senegal.

Cultural ambassador

Youssou has been an ambassador for UNICEF and the World Food Organization and has pioneered music projects for the Red Cross and the UN. Through his friendship with Bono and other high-profile performers he joined the ranks of musicians working for the good of humanity. When Bob Geldof organised Live Aid in July 1985, Youssou was onstage at Wembley Stadium with Salif Keita and Sly and Robbie.

Youssou later joined Geldof and Bono in lobbying world leaders for the cancellation of debts accrued by developing countries. According to Geldof, the Make Poverty History resolutions passed at the Gleneagles G8 Summit in 2005 – including the cancellation of debt and doubling of aid to Africa – mean that seven of the ten fastest-growing economies in the world are now African.11 On stage the same year at the Live 8 concert in London’s Hyde Park, Youssou made this plea: ‘The debt cancellation is OK. The aid is OK, but please open your markets.’

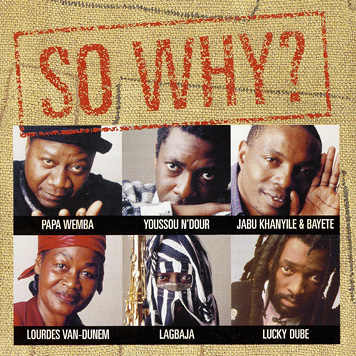

So Why?, an album co-written and produced by Wally Badarou for the International Committee of the Red Cross, was released in 1997 and carried messages of protest against ethnic cleansing and war in Africa. It includes contributions from Youssou who, to the tune of Bob Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom’, sang about unrest in the beautiful but troubled province of Casamance in southern Senegal. Papa Wemba (Congo), Lourdes Van-Dúnem (Angola), Lagbaja (Nigeria), and Jabu Khanyile and Lucky Dube (South Africa) made equally significant contributions.

56. So Why?

In 2000, refugee artists from a variety of countries gave a concert in Geneva to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The following year, in his role as artistic director for the event, Youssou invited eleven refugee musicians – including the Liberian Peter Cole, who had settled in Senegal, and the Zimbabwean Chartwell Dutiro who had fled to Britain – to record the album Building Bridges in his Dakar studio. When the album was released, Youssou said that he would like this music to reach out to all people, helping them to realise that exile could also happen to them, so that maybe then people would do more to help refugees.

In the same year, Youssou organised and headlined a concert in Dakar in support of efforts to combat malaria, a disease which is most prevalent in West and Central Africa and which at that time was killing around 1 million Africans each year. The Rollback Malaria concert, which also featured Angélique Kidjo, Salif Keita, Baaba Maal, Corneille, Orchestra Baobab, Oumou Sangare and Tiken Jah Fakoly, was filmed for television by British director Mick Csáky. The Senegalese designer Oumou Sy dressed ‘Mosquito Men’ on stilts who strode through the crowd, dancing with the audience.

Youssou continued his fight against malaria, appearing at a Malaria No More benefit concert at the IAC building in New York City in November 2010 in the company of other performers, including Goldie Hawn. Through his involvement with the campaign, he found himself drinking coffee in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington with George Bush, the man whose politics he despised (in 2003 Youssou cancelled a thirty-eight-week tour of the USA in protest at America’s invasion of Iraq, as he believed America had upset the entire world by waging that war without the support of the UN). Yet Bush proved sensitive to the cause, and as a result America doubled its support for the fight against a disease which has killed more humans than all wars, famines, plagues or natural causes put together.12

Youssou welcomed the election of Barack Obama not because he was black, but because he felt Obama was the best candidate. ‘Obama’, he remarked to me in Dakar in December 2010,

has set about rectifying ruptured relations between the United States and the rest of the world and that has a calming effect, like tropical rain after a period of intense heat. He understands that the future of Africa is in the hands of Africans. We will be asking Obama to help us trade freely so that we can receive a fair return for our products.

Along with Malian artist Rokia Traoré, Youssou has been a leading figure in the Association of Professional African Musicians. In Paris in February 2007, they both attended the Afrique Avenir forum to defend the interests of professional musicians and to promote investment in good causes.

When Yoko Ono donated the rights and music publishing royalties to some of John Lennon’s songs so that Amnesty International might encourage a new generation to stand up for human rights, Youssou chose to interpret the track ‘Jealous Guy’. It was one of twenty-eight tracks on a double album entitled Instant Karma: Save Darfur, which included contributions by U2, REM, Snow Patrol, Corinne Bailey Rae, Jackson Browne and Christina Aguilera.

International recognition

According to Senegalese academic Oumar Sankhare, author of Youssou N’Dour: Le Poète,

Youssou N’Dour’s art is harmonious, melodious, euphonious and eurythmic, a unique example in Senegalese music. The name of this singer will henceforth be written in the universal pantheon of great artists who have succeeded in imposing their particular aesthetic view on humanity. His international recognition is eloquent testimony to his universality.13

International journalists have lauded Youssou, praising his powerful voice, his talent and his ability to fuse world and pop music. Jon Pareles described him in the New York Times as ‘a musician who acts globally and hears locally’.14 In his 2008 biography Youssou N’Dour: le griot planétaire, Gérald Arnaud lauds Youssou’s 1992 album Eyes Open as ‘a treasure of soul music comparable with the most beautiful discs of Marvin Gaye, Al Green or Curtis Mayfield.’15

Thirty years on from his first ever trip out of Senegal, in May 2011 Youssou received an honorary doctorate from Yale University, which came with this citation:

As a singer, songwriter, and composer, your music melds African rhythms with traditions ranging from Cuban samba to hip-hop, jazz, and soul. You have created Africa’s leading ensemble, performed with great artists around the world, sung about tolerance, and acted with conviction, all the while remaining true to your own faith and culture. Understanding the power of music to liberate, heal and united [sic], you have organized and performed in concerts that call attention to injustice, poverty, and disease. With your extraordinary sound, you give voice to hope and our common humanity. We salute you now as Doctor of Music.16

The prestigious Polar Music Prize, which is worth 145,000 Swedish kronor (nearly £12,000) to each recipient, was founded in 1991 by the late Stig ‘Stikkan’ Anderson, the musical entrepreneur and former manager of ABBA. Previous recipients include Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Peter Gabriel, Gilberto Gil, Quincy Jones, Paul McCartney and Miriam Makeba. In 2013 it was awarded jointly to Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho and Youssou and was presented by King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at a gala ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall. Youssou’s citation was read by Swedish footballer Henrik Larsson:

A West African griot is not just a singer but a story teller, poet, singer of praise, entertainer and verbal historian. Youssou N’Dour is maintaining the griot tradition and has shown that it can also be changed into a narrative about the entire world. With his exceptionally exuberant band Super Étoile de Dakar (Dakar Star) and his musically ground breaking and political solo albums, Youssou N’Dour has worked to reduce animosities between his own religion, Islam, and other religions. His voice encompasses an entire continent’s history and future, blood and love, dreams and power.17

Youssou did not perform at the televised ceremony; instead, he enjoyed the luxury of watching Neneh Cherry, Carlou D and other artists interpret his music.

A further feather in his cap came in September 2017 when Youssou was presented with Japan’s Praemium Imperiale international arts prize, worth $136,000, for outstanding contributions to the development, promotion and progress of the arts. Following a ceremony in New York, where he received a gold medal and testimonial letter from His Imperial Highness Prince Hitachi of Japan, Youssou dedicated the award to the whole of Africa, with a message to African youth to believe in themselves and the continent. He also pledged to share a portion of the prize money, 75 million West African CFA francs (around £100,000), with his fellow Senegalese musicians. As UK journalist Rick Glanvill wrote of the star, ‘Senegal shaped a unique man.’18