13

The Source

Always conscious of the deep well of inspiration available to him through the musical gifts of his griot ancestors, musicians who served as entertainers, advisers, and keepers of history and lineage in the great courts of West Africa’s kings and emperors, Youssou N’Dour has often defined himself as a modern griot. Indeed, the notable success of his music and that of other musicians from Senegal, Mali, Guinea and Mauritania during the world music era can be attributed directly to that rich seam of music which has its source in the thirteenth-century royal courts of West Africa.

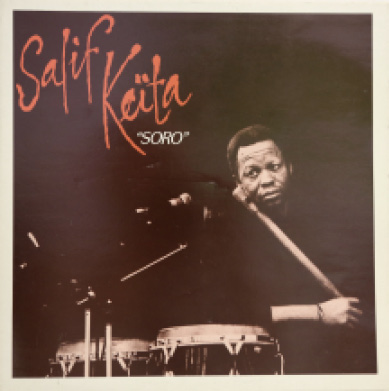

Salif Keita

The greatest patron the griots of West Africa ever had was Sundiata Keita (c.1217–55), who founded the Mali Empire, a federation of the Mandé people that endured for more than 200 years from its foundation around 1240. Its territories eventually extended right across the region from the shores of the Atlantic to the ramparts of Timbuktu and included modern-day Mali, Senegal and the Gambia, as well as parts of Mauritania, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau and the Ivory Coast. Sundiata’s court brought kingship to its highest level, as he was regarded as all-powerful; it is said that if he sneezed, his subjects beat their breasts in sympathy. The penalty for wearing sandals in the emperor’s presence was death, and all were required to cover their heads with dust as a mark of humility. The emperor alone wore a headdress and his regal clothing befitted his wealth and status, yet he never raised his voice. During Sundiata’s reign, the courtly traditions which allowed the griots to play a pivotal role as historians and entertainers were devised and developed.

Salif Keita’s noble family trace their lineage back to Sundiata Keita. Like his illustrious ancestor, who did not walk until he was seven years old, Salif emerged from an unpromising childhood to become one of the great soul voices of West Africa. Born in 1949 in the village of Djoliba, some fifty miles from the capital Bamako, he was an albino child who faced all the superstition and prejudice associated with such a condition in Africa; on the continent, albinos have even sometimes been sacrificed in order to bring good luck. The birth of an albino son so shocked and shamed Salif’s father – it was said such a child would bring bad luck for seven generations – that he initially banned his wife and baby from his compound, before relenting and taking them back. When, at Salif’s baptism ceremony, the hair on his head was shaven, the village women fought over it so they could sow it in the fields to fertilise the crops. As a result of his own condition (he describes himself as a black man with white skin), Salif Keita hopes for a world of mutual understanding and multiculturalism, and set up the Salif Keita Global Foundation to work for the fair treatment and social integration of people with albinism.1 Imagine his great pride when his niece Nantenin Keita, also an albino and whose photograph appears on his 1995 album Folon (The Past), represented France at the 2016 Paralympic Games in Rio de Janeiro and won the gold medal for the 400 metres.

Musically, Keita has achieved a remarkable fusion of Western and African traditions in his music. In Mali he listened to Pink Floyd and Rod Stewart, but his mighty album Mandjou, composed with Les Ambassadeurs in 1978, was an immediate hit in Africa. His next album, Soro, which was produced in France, was hailed as a classic crossover album which, together with Youssou’s album Immigrés, heralded the dawn of the world music era.

57. Folon.

In the spring of 1988, I travelled to Paris with TV journalist Robin Denselow and director James Marsh (who went on to make Man on Wire (2008), The Theory of Everything (2014) and The Mercy (2018)) to shoot a short film, Paris, Africa, about the rising popularity of African music in the French capital.2 Africa’s reggaeman, Alpha Blondy, provided the soundtrack with his song ‘I Love Paris’, and we interviewed the award-winning Senegalese band Touré Kunda. They were among the first West African musicians to bring their music to the capital, where they recorded seven LPs and a double album and gained three gold discs. Filmed at night against a backdrop of an illuminated Eiffel Tower, the trio looked as though they owned the place. North African music was represented by the Algerians Khaled and Fadela, and then we spoke with Salif, who was living in the suburb of Montreuil (popularly known as Little Bamako) and had just recorded Soro. A remarkable fusion of Western and African styles arranged by François Bréant and Jean-Philippe Rykiel, it was produced by Paris-based Senegalese producer Ibrahima Sylla. Robin Denselow described Soro in the programme as ‘a mix of synthesizers, subtle rhythms, brass and chanting African choruses, all topped up with one of the greatest soul voices to be heard anywhere in the world.’

In Paris, Africa Salif defined the global importance of African music using the image of a tree: ‘The roots are African music; the tree trunk is jazz and the branches and the leaves are funk, reggae, hip-hop and other modern styles.’

In 1989 I met Salif again, this time in Mali when I joined another BBC television crew led by director Chris Austin and cameraman Chris Seager to film Destiny of a Noble Outcast, a documentary for the arts series Arena.3 We were introduced to Salif’s mother and father in the village of Djoliba, where the apparent simplicity and harmony of their life gave no clue to the emotional turmoil they had experienced when their eldest son was young. Throughout Salif’s childhood, griots came to the Keita household to sing the praises of that noble family. It seems Salif was a brilliant pupil at school but his poor eyesight prevented him from following his chosen career as a schoolteacher, so he overturned all the rules of the caste system to become a singer like the griots who praised him. (He would later boast that singing is the most noble of professions, but in those early days it was tough going for him.) He slept in the market in Bamako; he listened to Pink Floyd and Rod Stewart; he sang in bars, strumming his own accompaniment on an acoustic guitar, someone slipping a coin beneath the guitar strings every now and again. Whenever it all seemed hopeless, Salif would sit alone on a hill above the city and reflect on his fate. At last he joined the Rail Band at the Buffet de la Gare and began to find his way. In the railway station’s courtyard, the Rail Band, who were paid as civil servants, performed for local punters, who were joined at two or three in the morning by passengers arriving at the station on their way to or from Senegal and Niger. So popular was the group that some people would leave Dakar on a Friday night and take the train to Bamako in order to dance to their music. During a brief absence, Salif’s place was taken by a certain musician and singer called Mory Kanté, who would later gain international acclaim for his kora playing and the hit song ‘Yé Ké Yé Ké’. So Salif turned on his heel and went down the road to the Motel to join Les Ambassadeurs, his only stipulation being that they should buy him a Mobylette moped. The group’s musicians came from Guinea, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Ghana as well as from Mali, hence their name. Under the coloured lights of the open-air stage, they serenaded visiting diplomats and tourists with their interpretations of the latest Charles Aznavour, Otis Redding or James Brown hits; in short, every kind of music except African. Salif wanted to change all that and modernise the traditional music of Mali, with all its riches. In 1978, following an attempted coup in Mali, he left the country in the company of Kanté Manfila, Ousmane Dia, Sambou Diakité, Ousmane Kouyaté and Alpha Traoré. They headed for Abidjan in the Ivory Coast, at that time the centre of all the musical action, and it was not long before they had created their first and most famous song, ‘Mandjou’, a praise song dedicated to Sékou Touré, the Guinean president. It became the title track on an album that was an immediate hit in Africa. Listening to it for the first time in my flat in Chiswick, the magic of ‘Mandjou’ kept me housebound and spellbound for an entire weekend:

58. Soro.

Touré don’t cry. Touré don’t be sad, for God has given

you all the gifts he has to give, including that of making music.

We filmed Salif walking in the fields around Djoliba, projecting his powerful voice in the way he had as a young man to strengthen his vocal chords. We filmed him in the marketplace in Bamako, at the Buffet de la Gare, and at the abandoned Motel.

Back in London, when the film returned from the processing labs, two key sequences were missing. The first featured a ritual dance by village hunters including Salif’s father, Sina Keita, and Salif himself, all dressed in full ceremonial costume and bearing guns. The second sequence contained footage of Salif at the cliffs of Bandiagara in remote Dogon country, an area well known for its deep spiritual traditions. Dogon legends describe the visit of extraterrestrial nommos, a race of mermen and mermaids who came from the Sirius star system.4 Could it have been that the solitary figure who appeared on a cliff just as Salif performed a song to his own guitar accompaniment had been angered by our intrusion upon this sacred site? Whatever the reason, it seemed clear we had contravened some local law, and so the director and the cameraman returned to Mali to reshoot both sequences, this time with the necessary permissions.

59. Mandjou.

60. Salif Keita with the author.

Although most Malians embrace the Muslim faith, many also believe in what they call ‘African realities’. When we met Salif Keita’s mother-in-law, Tenin Traoré, a well-known healer and clairvoyant and the subject of his song ‘Tenin’, she offered to read her cowrie shells for us. She explained that she had inherited her spiritual powers from her grandfather, Adama, and claimed she had met Mamiwata, West Africa’s legendary water spirit. Tenin prescribed for me the sacrifice of a goat and a ritual herb bath. She then poured a murky potion over my body and I accompanied her by the light of the moon to the local cemetery to bury the goat’s eyes.

61. Tenin Traoré.

Miriam Makeba, whose mother was an isangoma (traditional healer/diviner), defined those realities thus: ‘The spirits of our ancestors are ever-present. We make sacrifices to them and ask for their advice and guidance. They answer us in dreams or through a medium like the medicine men and women we call isangoma.’5 Zimbabwe’s top musician, Thomas Mapfumo, who was brought up a Christian, thinks that those who have passed on are closer to God. When I interviewed him, he explained the spiritual nature of his chimurenga music and described his respect for his ancestors: ‘They can speak with Him; maybe they are living with Him. So, through mediums, we have to consult our ancestors and tell them what messages we wish to convey to God.’6

In her book Obama Music, Chicago-born writer Bonnie Greer notes how that same African spirituality was carried by the slaves and their music to the Americas. She writes,

The blues has this quality of the ‘other world’, of that great African Triad of the living, the dead, and the unborn.

This Trinity exists together and at once in the African consciousness and it was brought over with the Passage.

The blues are full of the knowledge of this.

Growing up, we respected the dead because, well, they weren’t gone.7

Perhaps it is these deep atavistic connections with the land and the spirit world that are beguiling to Westerners like myself, who, once we visit Africa, feel drawn again and again to the continent. Traveller and writer Ryszard Kapuściński puts it this way:

For centuries people have been attracted by a certain aura of mystery surrounding this continent – a sense that there must be something unique in Africa, something hidden, some glistening oxidizing point in the darkness which it is difficult or well nigh impossible to reach.8

My lasting memory of my first trip to Mali was the feeling of humility and awe that came from standing alone beneath a starry sky looking out over the savannah plains of that immense land mass. Doris Lessing, who grew up in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), summed up this sense of vastness when she said, ‘Africa gives you the knowledge that man is a small creature, among other creatures, in a large landscape.’9

On his first visit to Mali in 1983, Youssou was moved by the enthusiastic and generous welcome he received. In fact, the attraction was mutual: Malian star Ali Farka Touré joked that the divorce rate increased sharply after Youssou’s concert, so numerous were the Malian women who defied their husbands to attend! The trip held special significance for Youssou because it was the first time he had played outside of Senegal. To receive such a warm reception in a country with extremely high musical standards gave him enormous confidence and an assurance that his music could travel. He was also thrilled to meet Fanta Damba, a singular and unsurpassed singer whom he regarded as the first lady of Malian music, and whose song, ‘Haye Hane’, he later reprised in his own majestic composition, ‘Wareff’.

I remember driving through Dakar with Youssou at the wheel and Fanta Damba’s cassette playing in the tape deck and Youssou humming and gently moving his shoulders in time to that sublime music. It is clear from Youssou’s song ‘Bamako’ just how much Mali held him in its spell. The image of a lady wrapped in her shawl is enveloping and alluring; she appears to be Youssou’s muse and inspiration. Could it be that he is in fact referring to Fanta Damba? Feelings of mystery and nostalgia pervade the song as Youssou’s voice soars to its topmost notes above the sweet voices of the Martyr of Luganda church choir. He repeats his longing in the phrase ‘Duma fatte, fatte, fatte Bamako’ (‘I shall never forget Bamako’).

.jpg)

62. Fanta Damba.

Ali Farka Touré

The late Ali Farka Touré greatly admired Youssou’s enterprising spirit and his voice. Youssou pays homage to Ali Farka in the style and tone of his 2007 album Rokku Mi Rokka (Give and Take), which features the gifted Malian xalam player Bassekou Kouyaté on many of its blues-tinged tracks.

Before he became a full-time musician, the great Malian bluesman was a farmer, a radio engineer, a driver, a desert guide and an ambulance boatman. He might equally have been a healer, a marabout, or even a king, as he came from a noble line of Songhai and Amarak warriors and generals. Ali was the youngest of ten children but the only one to live to manhood. When he was two his father died from injuries sustained fighting on the French side in the trenches of World War II. A pacifist, a teacher, a nature lover and an artist, Ali refused conscription when his time came. When he played the N’jarka fiddle, he conjured up the desert landscapes, the haunting solitary places where he loved to hunt. He told me that it was by a lake near his village that he first encountered the Ghimbala, the powerful water spirits that took hold of his little djerkele guitar, sending him into a trance as he played it.

His grandmother, Kounandi Samba, priestess of the Ghimbala, passed on to Ali the secrets and rituals of her traditional religion, but when he was eighteen he was, in his own words, ‘cured’ by a religious marabout and renounced these practices, pledging his allegiance to Islam at the great mosque at Timbuktu, the fabled city founded in c.1080 by the Tuaregs. From then on Ali prayed five times a day; if he missed a certain prayer, he would make up for it with extra prayers in the early morning. He might pray all night if he had a special trip to make. These rituals were as important to him as tuning his guitar or checking sound levels. I recall how he gave me a mantra, presumably one he used himself, which I still recite for safekeeping while taking off and landing in an aeroplane. Indeed, Ali never travelled without his protection kit – a bundle of herbs and resins to cure all aches and pains and a collection of talismans, each with a special significance, carefully tied to his body or pinned to his dress before every concert. An acute awareness of evil eyes may have accounted for a certain irascibility, and he was known to berate his audience if he thought they were not listening or appreciating as they should! His pride would not let him forget any behaviour which was less than generous towards him or his music.

The N’jarka and the djerkele were to remain his primary source of inspiration, providing a seemingly endless spring of melody. He transferred the same technique he used to play these simple instruments to the acoustic or electric guitar, tuning them in his own mysterious fashion, much to the bewilderment of those schooled in orthodox tuning methods. Although austere in his religion, he smoked cigarettes and savoured the odd tot of whisky, especially when he was in Scotland. His prodigious memory made up for the fact that he could not read or write – he could give you a day and date for every event in his own life, or for important events in his country. He danced the rumba or the bebop with enormous ease and elegance, just as he did any of Mali’s many traditional dances.

Among Ali Farka Touré’s favourite artists were Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Otis Redding, Jimmy Cliff and James Brown. When he first heard John Lee and Albert King he swore they must be Malian, so closely did their music relate to his own. Nevertheless, he learned a great deal from them in terms of technique. ‘If one day I am lucky enough to meet John Lee Hooker, I shall die happy,’ he said.10 Yet he would never deny the root source of his own inspiration – the natural blues of his desert songs; the dance rhythms of the nomads, the mysterious men in blue; the lore of eight different dialects including Tamashek, Songhai, Bambara and the Arab inflections which are echoed in his guitar lines.

Ali was a many-faceted man who, over the years, brought home tales of his trips to Russia, Bulgaria and many European countries, and since he was a keen photographer, he had albums full of snaps to prove it. Also in his luggage would be a new tailored suit or a remarkable hat, for he prided himself greatly on his appearance. In London he had his eye on a tuxedo complete with patent black shoes and bow tie; since cotton materials came cheaper in the shops in Willesden Green or London’s New Street market, his Malian tailor would soon be busy with yards of heavy cotton bazin in brilliant royal blue, deep russet, or pure white, fashioning long, flowing boubou robes.

63. Ali Farka Touré with the author.

When Ali’s first wife died in childbirth he was grief-stricken and swore he would never marry again; he did in time, of course, and his son Vieux Farka Touré is now a well-known musician. He also married Henriette Kuypers, a young Dutch woman, with whom he had three children, and it was touching to see her dancing onstage during Vieux Farka Touré’s concert in Amsterdam in 2011.

Always extremely courteous towards women, Ali would gallantly say, ‘ce que femme veut, Dieu le veut’ (‘whatever woman wishes, God wills’). A good friend and a gentleman in the true sense of the word, he used to tell me I was a Peul from among the herding nomadic people of West Africa and he would tease me by calling me ‘Jenny Diallo’, a name common among that ethnic group. And then, of course, I married a Senegalese man named Sow – who is in fact Peul!

Ali was also generous; old and young came to his house each morning to receive the few coins that would support them through the day. He always spoke fondly of his farm on the shores of the Niger River at Niafunké near Gao in Northern Mali, where his entire family were engaged in farming, tending flocks and growing crops. In 2012 and 2013, the area around the cities of Gao and Timbuktu was occupied first by MNLA (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad) rebels who aimed to establish an independent northern state for the Tuareg and later by Islamist groups including Ansar Dine, who imposed strict sharia law. Ali’s wife and many of his family moved to Bamako for a time, though most of them later returned. When, in late 2015, Vieux Farka Touré was asked how his father would have felt about the violence, the political instability and the financial ruin in his cherished homeland, he replied, ‘I can’t say, it would have hurt, but he wouldn’t have left Niafunké, that’s for sure. He would have done everything to stop the destruction because, believe you me, it’s been devastated.’11

Ali won his first Grammy award for Talking Timbuktu, the album he recorded with Ry Cooder, and a second for In the Heart of the Moon, his collaboration with ace kora player Toumani Diabaté, who traces his griot ancestry (griots are known as jalis in Mali) back in an unbroken line through seventy-one generations to the first kora player, Tiaramagau.

.png)

64. Vieux Farka Touré.

When he was diagnosed with cancer Ali faced his illness with stoicism and exemplary bravery. He insisted on leaving all his affairs, including his Niafunké farm, in good order. I attended his final concert at the Barbican in London in June 1995 and spoke again with him in Paris not long before he died on 6 March 1996, aged sixty-seven.

Baaba Maal: yela and reggae

Rising in the Fouta Djallon mountains in Guinea, the Senegal River passes through Mali, embraces Senegal in a large curve, forming the border with Mauritania, before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean at Saint-Louis. The river played a crucial role in the Atlantic slave trade, becoming a highway for the transportation of slaves from territories in the interior to the seaport. It has been a constant source of inspiration for Baaba Maal, who was born in 1953 in Podor, a town that sits on the banks of the Senegal River. His father was a fisherman and a muezzin, who with his sonorous voice called the faithful to prayer, while his schoolteacher mother taught him the customs of his own Toucouleur people, their dances and their songs. Baaba spent many years with a group of traditional musicians, the Lasli Fouta, travelling up and down the river and gaining first-hand knowledge of daily life in the region; of the men and women who work in the Walo flood fields where millet is grown from November to June and in the Dyeri lands higher up. He noted how the village girls made themselves pretty for the arrival of a relative or friend on the riverboat, the Bou El Mogdad, which made the round trip from Saint-Louis to Kayes in Mali. During their regattas, the northern fishermen would call up the spirits of the sea with their pekane music. The warrior caste sang about their heroes in a style called gumbala. The butchers had their own sawali music and the weavers plaited their threads to the dilere. The Toucouleur people dance the ripo, the tiayo, the ndadali or the odi boyel, while the dance of the virgins, the wango, is so strenuous that only the unmarried are supposed to be able to perform the high-kicking steps.

Listening to the praise songs the griottes sang at weddings or those of women pounding grain in family compounds, Baaba discovered the yela which was to become his trademark, a swinging beat regarded by Jimmy Cliff as the original reggae.12 Indeed ‘reggae’ in the African Soninke dialect means ‘to dance’. Explaining the evolution of his own musical style, he had this to say:

If you listen to the women of the Bundu in Southern Senegal as they sing and dance their yela, you will notice that the way they clap their hands resembles the beat of the rhythm guitar when we play it and the alternating drumbeat represents their accompaniment played on a simple kitchen calabash. When Africans are modernising their music, they bring out what is in their own traditions, and there are definite similarities between that music and the music of black people in Jamaica or America.13

As with so many African rhythms, it is likely that yela went to the Americas with the slaves and eventually became a universal beat, achieving ultimate worldwide popularity through the music of Bob Marley.

A clever student, Baaba read law at the University of Dakar, then music at the city’s arts school and later at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. In 1985, he formed the group Dande Lenol, meaning ‘The Voice of our People’, to reflect the particular lifestyle of the Pular-speaking ethnic groups of his own region. The Peul and the Toucouleur were pastoralists, although the Peul guarded their nomadic status longer than the Toucouleur, who intermarried with sedentary Serer groups to settle in the region called Fouta Tooro. When Baaba Maal and his group celebrated their first anniversary with a concert at the Sorano Theatre in Dakar in 1986 they quickly acquired a nationwide following, and when Baaba later signed a recording contract with London label Palm Pictures, a subsidiary of Island Records, Youssou now had a serious rival both at home and abroad. In Mansour Seck, a blind griot musician, Baaba found a musical companion with whom he wrote songs for a moving and memorable acoustic album, Djam Leeli. It was this music that first seduced international audiences, especially in the UK. When they showcased the album at London’s Hackney Empire, the concert was filmed for the BBC’s television series Rhythms of the World.14

In the same week, Peter Gabriel invited Baaba Maal to record vocal lines for the soundtrack which he was composing for Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). My friend Lucy Duran and I drove him to the Real World studios. Lucy was at the wheel, Mbassou Niang, Baaba’s manager, was in the front seat, and I sat in the back between Baaba and his keyboard player, Hilaire Chaby. We chatted along the way and then Baaba, who rarely spoke about his personal life, began telling me about his mother, whom he clearly adored, who had supported him in his chosen career, and who died when he was a student in Paris. Describing her warmth, generosity and kindness, he said fondly, ‘I think about her every day. What hurt me most was the fact that I was unable to return home from Paris to see her before she was buried.’ As he spoke, tears welled up in his eyes, and my heart went out to him. Afterwards we sat silently side by side, yet he seemed to take comfort from the sharing of such a profound loss. As if to diffuse the sadness Lucy stopped the car at a lay-by, and we stepped out to admire the breathtaking view down the By Brook valley towards the village of Box.

66. Baaba Maal with the author.

65. Baaba Maal at the Real World studios.

On Peter Gabriel’s album Passion, Youssou’s voice is heard on the title track alongside that of the great Pakistani qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and English boy soprano Julian Wilkins.

Baaba’s recording for ‘A Call to Prayer’ reflects his own spiritual nature and appears on the companion album Passion – Sources. His contract with Palm Pictures afforded him the freedom to collaborate with producers and artists from the world of pop and electronic music on albums such as Firin’ in Fouta, Missing You (Mi Yeewni), Nomad Soul, Television and, in 2016, The Traveller, produced by Johan Hugo Karlberg. Baaba Maal’s soaring vocals echoed over the Wakanda hilltops of the much-publicised 2018 blockbuster movie Black Panther; Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson spent a month in Senegal familiarising himself with African music and making recordings which included Baaba’s significant contributions to the film score. The soundtrack won the Oscar for Best Original Music Score at the 2019 Academy Awards ceremony in Los Angeles.

Alpha Blondy

Youssou and I travelled to the Ivorian capital, Abidjan, to attend a meeting. While we were there we lunched with his friend Alpha Blondy, the country’s leading reggaeman, voice of the dispossessed and idol of the gangs in Abidjan’s Treichville district. We drove in Blondy’s pale blue Volkswagen Beetle to Cocody, the seaside suburb which gave its name to his album Cocody Rock!!! As we sat at a beachside restaurant under the shade of coconut trees, I reflected that Blondy had come a long way since his troubled childhood when he had been moved from pillar to post, from Dimbokro to Odienné and Boundiali to Korhogo, where he was eventually expelled from his secondary school.

Born Seydou Traoré on 1 January 1953 to a single mother, he was brought up by his grandmother Nagnêlê until his mother married a man named Koné whom he disliked but who gave him a new surname. Then he formed a band called The Atomic Vibrations and took on an entirely different identity, that of Elvis Blondy. He was just twenty when he moved to Monrovia, where he learned English and taught karate to the sons of the future president, Samuel Doe. From Liberia he travelled to New York, where he faced altogether new challenges and where his frustrations resulted in a spell in a psychiatric hospital. The French journalist Hélène Lee, who knows Alpha well, said, ‘He is not mad, he belongs to another world, that of the extraterrestrials or simply that of Africa’s tomorrow.’15 All the same, it was at Central Park in 1975, during a Burning Spear concert, that he discovered his true vocation.

By a quirk of fate, he was spotted in a Greenwich Village club singing ‘War’ by Bob Marley’s producer, Clive Hunt, who was briefly interested in working with him but failed to follow through on the idea of creating the first ever African reggaeman. Disillusioned, Blondy returned to the Ivory Coast, turned another page in his career and adopted a new name, the one that stuck: Alpha, meaning the beginning. In Abidjan, he worked at the TV station and engineered an appearance on a show called Première Chance, where a TV producer, George Benson, arranged a recording session for him which culminated in the album Jah Glory, sung in English, French and his mother tongue, Diola. One magic track, ‘Brigadier Sabatier’, about police brutality, sent shock waves around the country and the whole of West Africa. Ten years later, his song ‘Apartheid is Nazism’ set a precedent for many of his overtly political songs.

In 1986 he travelled to Kingston, where he recorded the album Jerusalem accompanied by the legendary Wailers, Bob Marley’s group, and produced by Tuff Gong. Then with his own band, The Solar System, he recorded Revolution (1987), The Prophets (1989) and SOS Guerre Tribale (1991), all of which contained lyrics that denounced dictatorships, division, repression and tribalism. Asked why his songs are so political, Blondy replied that he is an ordinary Ivorian who reads newspapers, watches TV and listens to the radio. As for religion, this son of a Muslim father and Christian mother claimed that he respects all religions that respect God. ‘God is against war and the people that want to fight holy war are mistaken. They are going to hell because God said, don’t kill.’16

67. Apartheid is Nazism.

Released in 1998, an album named after and dedicated to the assassinated President of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin, confirmed Blondy’s fascination with a country where Jews, Christians and Muslims try to coexist. It featured vocals by Rita Marley and Marcia Griffith and was produced by none other than Clive Hunt, whom Blondy had met again by chance in a hotel lobby in Paris. One of the tracks, ‘Guerre Civile’, offered a prophetic warning of the dangers of civil war between ethnic groups in Africa, and as it turned out, in the Ivory Coast.