14

The Great West African Orchestras

Orchestra Baobab

Early in the year 2000, a miracle happened. Nick Gold, managing director of World Circuit Records in London, who had already licensed tracks by Orchestra Baobab for the album Pirates Choice, had for some time been mulling over the idea of reuniting the group, which had disbanded in 1987. When I was asked to propose Senegalese bands for a Dakar Night at the Urban Vibes festival at London’s Barbican Hall, I immediately suggested a comeback concert by Orchestra Baobab. By then I was working in Dakar as international liaison manager for Youssou’s music operations and he was fully supportive of the idea of a reunion: the Orchestra, along with other legendary West African bands including the Senegalese group Xalam, Guinea’s Bembeya Jazz and Gambia’s Super Eagles, had been a seminal influence on his early life and career.

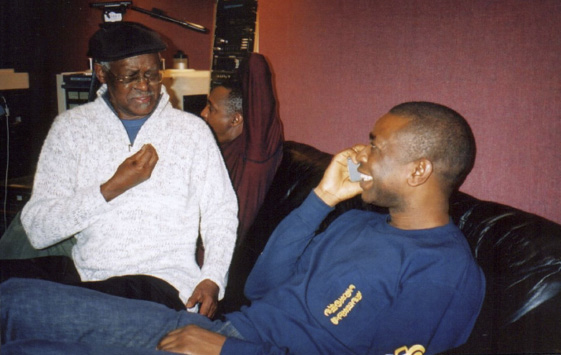

68. Orchestra Baobab with well-known Senegalese photographer Behan Touré.

I telephoned Barthélémy Attisso in Togo and persuaded him to return to Dakar for rehearsals. Balla Sidibé, Rudy Gomis and I met him off the plane at Dakar airport, and a meeting over lunch at Terrou-Bi in Dakar, where we were joined by Issa Cissokho, Latfi Bengeloune and Thierno Koité, sealed the idea of a comeback. Thus the legendary Orchestra Baobab came back to life, intact save for the voice of the late lamented Laye Mboup who, at Youssou’s suggestion, was replaced by a remarkable young singer called Assane Mboup (no relation). The London concert was deemed a success. Writing in the Guardian, Robin Denselow described it as a ‘subtle, charming, triumphant reunion’, although he thought the group’s green floral-patterned shirts made them look like an old-fashioned hotel band.1

Orchestra Baobab were originally formed in Dakar in 1970 when a group of Senegalese personalities, including Ousmane Diagne, Dame Dramé and government minister Adrien Senghor, decided to create an intimate club where they could meet with their friends. They took over the basement of number 144 Rue Jules Ferry, a stone’s throw from Independence Square and the presidential palace. The ceiling and walls, moulded to resemble the knotty trunk and branches of a baobab tree, were decorated with monkey skins and wicker lampshades. The Baobab Club was quite simply the trendiest and chicest venue in the city.

Baro Ndiaye (saxophone), the first bandleader, and Sidathe Ly (bass guitar) chose the other band members. Moussa Kane played congas and toumba; Bitèye was the kit drummer while Barthélémy Attisso from Togo, who was studying law at the University of Dakar, became lead guitarist. The singers Balla Sidibé (who also played drums, guitar and congas) and Rudy Gomis were enticed away from the Star Band at Ibra Kassé’s Miami Club. Laye Mboup, the charismatic star of the National Troupe at the Daniel Sorano Theatre, came with his stunning good looks, his local griot singing talents, perfect pitch and a wealth of Wolof songs.

By the late 1950s, Senegal and neighbouring countries, including Guinea and present-day Mali (then called French Sudan), were seeking independence from colonial rule, and their growing political links with Cuba served to popularise Cuban music. Cuban son, which emerged around 1905, spawned other Cuban, Latin American and Caribbean styles including cha-cha-cha, mambo, rumba, pachanga and merengue in the Dominican Republic, calypso in Trinidad and Tobago and eventually, in the 1960s, salsa. This dance style first emerged in Venezuela and was popularised in New York by Johnny Pacheco, Ray Barretto and Rubén Blades. When it reached Senegal, salsa was played by the local groups Star Band and Miami, and became all the rage. What came to define Orchestra Baobab’s repertoire was their intriguingly cool mix of pachanga, salsa, cha-cha-cha and African music. Initially the group animated the Baobab Club at weekends, but they quickly gained so many fans that they were playing every night and the dance floor was full by ten o’clock. Since the musicians were drawn from many ethnic groups, they had an extensive repertoire of popular songs which included something for everyone. Balla Sidibé and Rudy Gomis and later Charlie Ndiaye (bass guitar), who were all born in the southern Senegalese province of Casamance, contributed Mandinka, Mandiago and Diola folk songs. Médoune Diallo represented Toucouleur music from the north of Senegal. Issa Cissokho (tenor saxophone) and his cousins, Mountaga Koité (drums) and Seydou Norou ‘Thierno’ Koité (saxophone) drew inspiration from their Malinké relatives in Mali. Latfi Bengeloune (rhythm guitar) was born in Saint-Louis of Moroccan parents, while Peter Udo (clarinet) was Nigerian. Barthélémy Attisso added touches of Togolese, Congolese and other Central and West African musical styles to his arrangements. Laye Mboup and Ndiouga Dieng, Wolof singers from the major ethnic group in Senegal, came with the praise-singing traditions that put the final Senegalese stamp on the music.

During the 1970s Orchestra Baobab were hailed as the best band in Senegal if not in Africa, enjoying a status similar to Bembeya Jazz in Sékou Touré’s Guinea. The founding members stayed firmly with the group, but they welcomed regular guest musicians and singers. Despite his natural talent, Laye Mboup was unreliable, finding it difficult to cover his commitments with both the Sorano Theatre and Orchestra Baobab, so the group looked around for a stand-in singer. At his audition, the young and very promising Thione Seck sang ‘Demb’, a tribute to his mentor Laye Mboup, and was accepted without hesitation, as was his younger brother, Mapenda Seck. In 1975, when the twenty-seven-year-old Laye Mboup was killed in a tragic car accident, rumours of a spell cast by a jealous husband surrounded his death.

Apart from the Baobab Club, the group were invited to play on state occasions, such as a soirée to celebrate the nomination of Abdou Diouf as prime minister. They were the star attraction at glamorous army and navy dress dances at the Mess des Officiers and they also appeared at the Lions Club, the Zonta Club and the Soroptimist Club. They livened up the New Year’s Eve Ball in the southern town of Ziguinchor, which was held to raise funds for municipal improvements there. In 1978 they played at the wedding reception of Pierre Cardin’s daughter in an expensive venue frequented by the glitterati near the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Four years later they performed on the Casamance Express passenger boat during its inaugural trip, travelling from Dakar to Ziguinchor and on to Conakry in Guinea, where they appeared at the Palais du Peuple. The Guineans, who were seduced by Barthélémy Attisso’s rapturous guitar solos, loved ‘On Verra Ca’ (‘We’ll See About That’), as did President Sékou Touré, who made a habit of using that phrase in his daily discourse.

In 1979 the Baobab Club closed down and Orchestra Baobab moved to the Ngalam nightclub at Point E, next door to the fashionable Lebanese-owned patisserie Les Ambassades. A small but delightful venue, its mirrored walls reflected the revellers on the intimate dance floor. It was here in 1981 that Moussa Diallo from Thies recorded a live session with his four-track Nagra and the musicians signed a recording contract with Mbaye Gueye. Wahab Diawo, the owner of the Jandeer nightclub (later called the Kilimanjaro), invited Orchestra Baobab to play at his place. Madame Michelle, who ran the Balafon, booked the orchestra for her club at the Immeuble Macodou Ndiaye. At the height of their popularity, Orchestra Baobab commanded a very respectable fee of 1,800,000 West African CFA francs per night (about £3,000 in today’s money).

In 1982, the twenty-three-year-old Youssou N’Dour, who had formed his first band and introduced a new wave of popular mbalax dance music based on the rhythms of traditional sabar drums, emerged as a surprise rival to Orchestra Baobab with their more leisurely and languid dance grooves. By 1985, in what proved to be a vain attempt to update their style, the group introduced sabars and female singers, but in 1987, after a difficult tour in France, Orchestra Baobab began to disintegrate. One by one the musicians left to join other bands, and Issa Cissokho and Thierno Koité joined Youssou and the Super Étoile de Dakar. Barthélémy Attisso resumed his work as a lawyer in Togo. Balla Sidibé joined Pape Fall and his group African Salsa, while Rudy Gomis took a day job as a teacher. So ended the first chapter of the Orchestra Baobab story.

In 2001, when a new album, Specialist in All Styles (the very title indicated a renewed confidence in their music), was recorded by the revived Orchestra Baobab at the World Circuit studios in London, Youssou co-produced it and sang on the track ‘Hommage à Tonton Ferrer’ along with Ibrahim Ferrer of the celebrated Cuban group Buena Vista Social Club.

The album topped the world music charts and earned Orchestra Baobab the prize for best African group at the BBC Radio 3 Awards for World Music. It also assured the musicians of regular international tour dates. In March 2003 they performed at the charity event Le Bal de la Rose, organised annually in Monaco by Princess Caroline in aid of the Princess Grace Foundation. For this event, staged at the Monte-Carlo Sporting Club on the Avenue Princesse Grace, the band wore costumes designed by my sister-in-law, the late Fama Sow Cama, each one distinctive, each one imaginatively created with a fabric chosen to suit the individual musician. The costumes would have been scrutinised by Karl Lagerfeld, who was a guest at the ball. Dutch photographer Christien Jaspars took moody black-and-white photographs of the group and Matar N’Dour snapped them posing around a painted car rapide bus. It was no sinecure, however, to manage twelve macho men who had once told me, ‘If you had been a Senegalese woman, we would never have allowed you to do this job!’

69. Nick Gold and Barthélémy Attisso.

70. Youssou with Ibrahim Ferrer.

At the end of March 2017, Orchestra Baobab released a brand-new album dedicated to Ndiouga Dieng, one of their original vocalists, who had passed away in November 2016. In the sleeve notes, Nigel Williamson wrote, ‘As enduring as the mighty African Baobab tree from which the group derives its name, the veteran core of the band remains as strong and sturdy as ever.’ Caressed by their languorous, well-tempered dance grooves, soothed by the warm welcoming voices of Balla Sidibé, Cheikh Lô (‘Magnokouto’) and Thione Seck (‘Sey’), charmed by lyrical guitar lines and glissando kora riffs, thrilled by Issa Cissokho’s exuberant tenor sax and Thierno Koité’s blowsy, bluesy sax solos, I realised once more why African music had seduced me all those years ago.

.jpg)

71. Tribute to Ndiouga Dieng.

Xalam

The Senegalese group Xalam II, who inspired Youssou to open his own music to new ideas, were at the height of their fame in the 1980s, rivalling Osibisa, Fela Kuti and Hugh Masekela. The Afro jazz fusion for which they became famous may have been influenced by Cream, Led Zeppelin, James Brown and Ray Charles, but it began as a truly innovative experiment in modernising traditional African tunes and songs. Who of their ardent fans can forget ‘Ade’, ‘Sidy Yella’ or ‘Djisalbero’?

In late 2008, the musicians, many of whom were now living in France, came together again in Senegal for rehearsals at the Quai des Arts in Saint-Louis, followed by reunion concerts in that charming city and in Dakar. At the invitation of Henri Guillabert, I was delighted to spend Christmas and New Year in their company. Abdoulaye (Ablo) Zon, an exceptional young drummer from Burkina Faso with a similar feeling and technique to that of the late Prosper Niang, had come on board. Jean-Philippe Rykiel had travelled from Paris. Vocalist Ibrahima Coundoul was there as, of course, was the inimitable Souleymane Faye, an original artist with a singular voice. At their eagerly awaited, sold-out show at the Just 4 U Club in Dakar, Souleymane Faye brought piquant humour, sartorial surprises and a suitcase to the stage. His costume had been fashioned to his own specifications by a local tailor from ten metres of luminous green taffeta. He later removed an outer boubou with matching scarf to reveal flared trousers and a bodice with an askari-style pleated skirt. In the audience was Pierre Hamet Ba, for whom Faye is the soul of the group. In a Dakar interview in January 2009 he told me,

Faye’s pictures of daily life derive from a very simple view of the phenomenon of human existence. He is very profound; he is very intellectual though his university has been the school of life and he is a complete artist. Others work at their art, but Faye is a natural genius.

72. Souleymane Faye with Xalam and suitcase.

In 2011, Youssou showed his respect and affection for Souleymane Faye by offering him a 4 x 4 vehicle to replace his ancient Citroën 2CV.

The Xalam story began on a tide of optimism and political fervour. The years following Senegal’s independence on 4 April 1960 were infused with a spirit of black pride, respect for indigenous customs and openness to whatever influences the outside world might bring. In the capital’s nightclubs Aminata Fall was singing her moody blues. Laba Sosseh, from neighbouring Gambia, was affirming his reputation as West Africa’s leading salsero by gaining a gold disc for his single ‘Seyni’. Dexter Johnson was in residence at Ibra Kassé’s Miami Club. Music stores like Radio Africaine and Disco Star were selling vinyl LPs imported from Europe, Cuba and the USA. An emerging bourgeoisie, who had settled in suburban villas at SICAP Amitié, attended Friday night music clubs, sharing their love of American soul, R & B and jazz. The groundbreaking group, named after the traditional African lute, was created by Professor Sakhir Thiam, an aspiring guitarist who subsequently became a minister in the Senegalese government. He was of a generation who listened to the Voice of America Jazz Hour presented by Willis Conover, broadcasting music by Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington. By 1970, the original Xalam formation featured Cheikh Tidiane Tall on guitar and Ayib Gaye on bass, Bassirou Lo (flute) and Diego Kouyaté (alto sax). The frontmen were Magaye Niang, Tidiane Thiam and Mbaye Fall. Their repertoire included salsa, paso doble and cha-cha-cha dance tunes as well as cover versions of James Brown, Otis Redding, Cream, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix, and they also flirted with jazz. Flamboyantly dressed in Sixties-style floral shirts, Abraham Lincoln jackets and flared trousers, the band set out on a year-long tour of neighbouring African countries, performing in Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and the Ivory Coast. Senegalese impresario Tanor Dieng, who organised the tour, remembered, ‘I was their doctor, psychologist, social worker and manager.’

73. Xalam.

Back in Dakar, while Orchestra Baobab were pulling crowds at the Baobab Club and the Star Band were still the main attraction at the Miami, leading musicians from Europe and the US regularly staged concerts in the city. Johnny Hallyday, Max Roach and Stanley Cole were among those who came to see Xalam at the Gamma Club, a popular venue situated on the corner of Rue Carnot and Rue Wagane Diouf.

Eventually the original Xalam musicians were eclipsed by their own protégés. Known as Xalam II, the new group was managed by Dani Gandour, son of a Lebanese peanut farmer from Casamance. Prosper Niang played drums, with Henri Guillabert on congas and guitar, and Ibrahima Coundoul joined Khalifa Cissé on percussion and vocals. The arrival of three talented graduates from the art school – Yoro Gueye on trombone, Ansoumana Diatta on saxophone and percussionist Moustapha Cissé – prompted a radical change of musical direction. Samba Yigo’s guitar was naturally funky and rock, while Ansoumana’s phrasing was uniquely his own and contributed significantly to the overall sound. Baye Babou, the bass player, who was inspired by James Brown and Ray Charles, set about deconstructing the harmonic patterns of jazz classics in order to understand them better. Percussionist Moustapha Cissé grew up in Dakar’s Fass district, where he began drumming during Lébou Ndeup and Mandinka Djina Fola rituals. Then, through his work with the National Theatre’s African Ballet and Mudra Afrique (Maurice Béjart’s modern dance school, directed in Dakar by Germaine Acogny), he amassed a repertoire of regional rhythms, especially those from Casamance. What also set him apart from other Senegalese percussionists was his knowledge of jazz, as his father owned an extensive collection of jazz LPs.

Xalam II found a house in the suburb of Liberté 6 which was quiet and spacious and where they could live and work together under one roof. Here they invited Fanta Sakho, Lamine Konté and other traditional singers to help them understand Sose, Serer, Wolof, Toucouleur, Mandinka and Pular traditions and language. Young, handsome and talented, they became the resident band at the New Experience Jazz Club and soon gained a growing fan base. ‘They were our Beatles,’ says my friend Clarice Mbodj. ‘We were all in love with them.’

In 1979, when Hugh Masekela invited Xalam to perform at a festival in the Liberian capital Monrovia, which was organised by the African National Congress (ANC) to raise funds for South African exiles, they arrived with a new song, ‘Apartheid’. Fela Kuti was there and Miriam Makeba together with her husband, Stokely Carmichael, the American civil rights and black power activist, who drove the Xalam boys home in his limousine after the show.

In the same year, Volker Krieger, a German musicologist and jazz-rock guitarist who was touring West Africa, asked Xalam to perform during the first part of his stage show in Dakar. Dressed in shrill red satin shirts, the group made a dramatic entrance from among the stadium crowd, raising a percussive storm of African rhythms as they approached the stage. They joined Krieger and his musicians for a big-band version of their own composition ‘Ade’. Krieger then invited them to take part in a festival in Berlin alongside the Brazilian star Gilberto Gil, and while they were there they used their concert fees to record their first album, Ade: festival horizonte berlin ’79, a calling card that would launch their international career.

During a Jazz Festival at the Club Med resort in Dakar, they found themselves eating at the grill bar with Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Jimmy Owens, Kenny Clarke and Stan Getz, who jammed with them onstage. Dizzy loved their track ‘Kanu’ for its jazz swing.

When in 1982 Xalam II moved to Paris, Prosper Niang became their natural leader. He recruited keyboard player Jean-Philippe Rykiel, son of French designer Sonia Rykiel, who professed a passion for Thelonious Monk and Frank Zappa as well as for electronic, classical and African music and whose keyboard samples replicated the sounds of the kora, marimba and balafon. From Dakar, Prosper brought Souleymane Faye and Seydina Insa Wade (vocals) and Cheikh Tidiane Tall (guitar).

74. Prosper Niang on drums.

Xalam II took part in Mamadou Konté’s first Africa Fête tour along with Manu Dibango (Cameroon), Ray Lema (Congo) and Ghetto Blaster from Nigeria, performing in London and Morocco and at various European festivals. In England they recorded Gorée, their first international album, at Ridge Farm studios in Surrey, where they were guests at the manor and played football on the lawn. The sound engineer handed a tape of their music to Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones, who promptly invited Coundoul and Moustapha Cissé to lay down percussion lines on the Stones track ‘Undercover of the Night’.

75. Xalam II’s percussionists onstage.

Xalam II toured in Japan and Canada with their new album Xarit, which was produced by Jacob Desvarieux, lead guitarist with Kassav. They appeared at the Nyons and Montreux Jazz Festivals; they met Arturo Sandoval and Irakere in Guadeloupe; and they supported Crosby, Stills and Nash at the Hippodrome in Auteuil, Paris.

In 1988 tragedy struck. Prosper Niang died of cancer aged thirty-five and the group gradually disintegrated, although some of those who remained in Paris represented Xalam II at Woodstock ’94, which marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the original Woodstock festival.

In 2015, Xalam II released a new album, Waxati, which boasted a splendid cover photograph of the group by photographer Matar N’Dour. By year’s end they were performing each weekend at the King Fahd Hotel in Dakar.

Gambia: Super Eagles

Back in the early 1980s, Youssou, Mbaye Dièye Faye, Ouzin Ndiaye, Marc Sambou and Balfort made their first trip beyond the borders of Senegal to Gambia, which was then at the forefront of the new popular music scene. What drew them most to Banjul was the success of the country’s top group, the Super Eagles, who were pioneering their Afro-Manding jazz. The group had formed in the mid-1960s, just as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were stirring up a musical revolution in swinging London. They too donned their Chelsea boots and took their second-hand Salvation Army uniforms, newly arrived from London, down to Leman Street in the Half-Die district of Banjul where Mamadou Diallo, otherwise known as Modou Peul, the best tailor in town, transformed them into trendy Sergeant Pepper suits complete with gold-stitched epaulettes. Living in an English-speaking state surrounded by eight francophone countries, Gambians had the advantage of being able to understand the latest British and American pop songs. Through the radio and newspapers and a growing tourist industry, they kept a hotline to London fashion and music.

Young enterprising enthusiasts like Oko Drammeh acquired copies of the London magazine Fabulous 208, which printed the lyrics of hits by the Beatles, the Monkees, the Rolling Stones and other top groups, then sold them at a keen price to the fans. Drammeh became the manager of the Super Eagles and their 1969 album, Viva Super Eagles, offered direct imitations of Western pop music sung in English, with only one or two African numbers. Keyboard player Francis Taylor, who was among the very first Africans to master the synthesiser, also played cricket for the Gambia. Paps Touray, the lead singer, was idolised then and since by the likes of Thione Seck and Youssou.

The Gambian village of Sérékunda had become a popular meeting place for musicians from Casamance (the brothers Touré of Touré Kunda), Guinea Conakry (Bembeya Jazz), Dakar (Merry Makers and Psychedelic), Mali (Salif Keita), Sierra Leone (Sabano Band) and Guinea-Bissau (Super Mama Djombo). Sustained by newly harvested palm wine, the artists exchanged ideas at Sunday afternoon jam sessions called hawares, which Drammeh organised in Banjul at the Swedish-owned Tropical nightclub on Clarkson Street.

Senegalese musicians Majama Fall and Cheikh Tidjiane Tall invited the Super Eagles to Dakar, where they lived in a large house in the Medina district and were joined daily by the brothers Diagne and young Omar Pene of the group Diamono. They played nightly in the Adeane Club, and by the end of their stay the Super Eagles had recorded an LP, Saraba, described on the album cover as ‘authentic music from the Gambia’.

In 1979, inspired by the example of Xalam, who had adopted an African name, the Super Eagles changed theirs to Ifang Bondi, a Mandinka word meaning ‘be yourself’. Back home in the Gambia, the group not only spent more time in the villages listening to traditional musicians like the great Jali Nyama Suso but they also began experimenting with jazz and different African rhythms.

Suddenly, with the attempted coup of July 1981, a state of emergency was declared in the Gambia. Public gatherings were prohibited and nightclubs closed. As a result, there was virtually no music for five years, and many musicians travelled abroad. Singer Moussa Ngom, like Laba Sosseh before him, moved to Dakar, where he joined the group Super Diamono, while kora player Foday Moussa Susu made for the USA to work with Bill Laswell and Herbie Hancock. Oko Drammeh was arrested by Yayeh Jammeh, the young rebel president. It is said he only survived imprisonment in a crowded cell with high windows because he was so tall; many of his fellow prisoners suffocated or died from heat exhaustion.

In 1984, Ifang Bondi travelled to Holland to record their seminal album Mantra, a nostalgic reference to the heady Maharishi-inspired vibes of the Sixties. This was a new Afro-Manding sound with bluesy, jazzy horns and African percussion topped by the inimitable voice of Paps Touray. Mantra remains a classic of the genre.

In that same year, when I returned to London from my life-changing trip to Senegal, I searched around to find someone who shared my enthusiasm for Youssou’s music. I discovered just one article in the magazine Country Life, written by Lucy Duran, whom I tracked down to the National Sound Archive. We met for lunch in a restaurant near the Royal Albert Hall and soon became firm friends and supporters of African music. Lucy will remember the day in 1986 when she and I drove Youssou and the Super Étoile to Heathrow Airport following their concert at the Town and Country Club. Imagine the scene at the hotel in Bayswater when it was discovered that one of the musicians had allowed the bathwater to overflow, causing the ceiling to collapse in the room below. With musicians, suitcases and instruments packed tightly into the hired minibus, Lucy, who was driving, led the way while I followed behind with Youssou and Mbaye Dièye Faye on board my royal-blue Mini. Before long the back door of the bus flew open, spilling luggage into the road, and a major traffic jam ensued.

Lucy had lived in the Gambia, where she had learned to play the kora with Amadou Jobarteh and where she married Amadou Sow, with whom she had two children, Amadou and Sira. Her home at Cantelowes Road in north London was an open house for many visiting musicians, who enjoyed the delicious African dishes she cooked as well as the animated after-dinner dance parties. Lucy wrote her doctoral thesis while she was a lecturer in African music at London’s School of Oriental Studies (SOAS). She also presented World Routes on BBC Radio 3 and has tirelessly promoted and produced the music of Mali, especially the work of Toumani Diabaté, whose composition ‘Cantelowes’ acknowledges her generosity and friendship. In 2017 she co-produced the album Ladilikan, featuring Trio Da Kali and the Kronos Quartet.

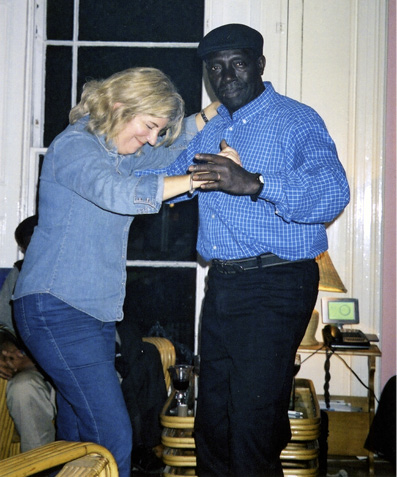

76. Lucy Duran dancing with Balla Sidibé.

Guinea: Bembeya Jazz National

Sékou Touré was the president of Guinea from 1958 – the year his country gained independence from France – until his death in 1984. He was the only leader in francophone West Africa to reject the terms of French president General de Gaulle’s proposals for independence, which included continued French cooperation. ‘Nous préferons la liberté à l’opulence dans l’esclavage’ (‘We prefer to be free even if that means being less well off’), protested Touré, and his country backed him up by voting an overwhelming NO in an independence referendum.2 While the president of the Ivory Coast, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, was inviting foreign investors into his country, and Senegal’s president Léopold Senghor was defending his thesis of negritude, enracinement et ouverture (black pride, authenticity and openness), Sékou Touré was promoting a cultural revolution in Guinea, banning all foreign music on the airwaves, disbanding existing orchestras who played only French or Western covers and financing thirty fully equipped new bands. These included Les Amazones de Guinée, an all-female group of police officers, and Bembeya Jazz National, who were carpenters, drivers, teachers and tailors by day and musicians by night. Bembeya’s epic song ‘Regard sur le Passé’, released in 1966 (which lasted over thirty-seven minutes, filling both sides of an LP), was regarded as a perfect synthesis of Guinea’s traditional and modern music. Its subject, Guinea’s national hero Almami Samori Touré, who mobilised resistance against French colonialism in the nineteenth century, was the grandfather of President Sékou Touré. This flowering of new Guinean music was recorded by the state-owned record label, Syliphone, which catalogued a staggering 800 songs, eighty-two LPs and seventy-five EPs between 1967 and 1980.

One of Sékou Touré’s first foreign visits as head of state was to Cuba, where he arranged study courses for Guinean students. This Cuban connection was to prove fruitful for the band; in 1966 Bembeya Jazz National performed in Havana, and in 1972 Fidel Castro visited Guinea.

Often referred to as ‘The Elephant’, Touré was a radical, charismatic and strict ruler, who delivered independence to his people.He was also a generous patron of the arts. All the same, following a military coup led by Colonel Lansana Conté in 1984, accounts of Touré’s time in government revealed that he was also a repressive despot who jailed his political opponents. Diapy Diawara, who for a time managed Bembeya Jazz National and subsequently distributed their discs and those of Les Amazones through his Paris-based company Bolibana, believes that Sékou Touré’s tyrannical side derived from the ill treatment he received at a French-run school. Diawara also claims that Touré was albino, but this was noticeable only in the colour of his eyes. It was said a clairvoyant had told him the precise day and time of his death – he died in America in March 1984 while undergoing heart surgery in a Cleveland hospital.3

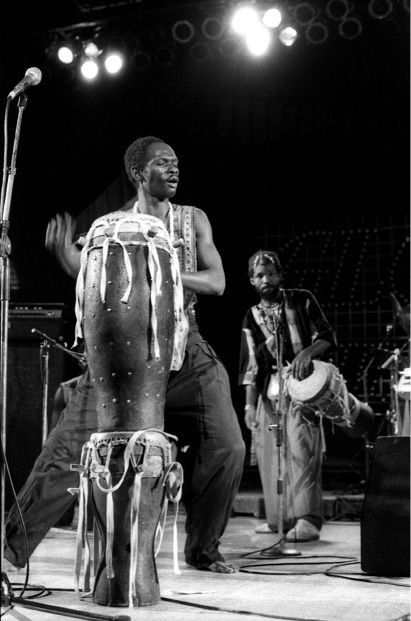

77. Bembeya Jazz National.

In 1989 Bembeya Jazz National played the Africa Centre in London. Even in that confined space they gave a spirited performance, with legendary lead guitarist Sékou Diabaté in fine form. He had acquired the moniker ‘Diamond Fingers’ after dazzling audiences at the 1977 Festac festival in Lagos with standout solos such as that on Bembeya’s track ‘Akukuwe’. When he was voted Best Artist at the festival his fans raised him aloft on their shoulders, a practice oft repeated throughout his career.

Sékou Diabaté was born into a griot family of famous balafon players in Kankan, 250 kilometres from Conakry, where his father bought him an acoustic guitar which Papa Diabaté, his cousin, taught him to play. When Bembeya Jazz National was formed, a car was sent to Kankan to fetch Sékou, since news of his fledgling talent had spread to the capital. A Hawaiian guitar added special character to his style, especially the melody lines, and a metallic six-string guitar gave him a powerful sound.

The day after their Africa Centre concert, I drove Sékou and Kaba to Kew Gardens, where we walked and talked and afterwards took tea in the North African-style comfort of Julie’s Restaurant in Notting Hill. In his deep bass voice, Sékou told me about the accident in Dakar in 1973 which had taken the life of Bembeya’s marvellous lead singer Demba Camara, an idol of the young Youssou and so many other rising stars.

78. Sékou Diabaté and Kaba at Julie’s Restaurant in London.

Bembeya had been invited to perform at the Sorano Theatre in Dakar on the eve of Senegal’s independence celebrations on 4 April. When the band arrived at the airport in Dakar they found that the Guinean embassy had sent a car for Sékou, who asked Salifou Kaba to accompany him. Demba wanted to come too because he felt tired and wished to rest. On a bend in the coast road at Ouakam, near the spot where the Monument de la Renaissance is now, the car lost control and tumbled onto the grass verge. As it rolled over, the car door opened, Demba fell out and and was found nearby, unconscious; he died later in a Dakar hospital. Sékou survived with only a bruise on his forehead, while Salifou sprained his ankle.

Everyone was deeply shocked by Camara’s unexpected death. The superstitious believed it was because the Bembeya musicians had that year omitted to sacrifice a black bull at the River Bembeya in Beyla. It took a full three months before the group felt able to perform again, though, in her book Rockers D’Afrique (1988), Hélène Lee contended that the group never really fully recovered from the loss of their talented friend and lead singer:

Musically they are still fantastic. But the presence of Demba, the star, was what made them exceptional, an extraordinary and bizarre phenomenon in those transitory times of new-found independence. And that is why the drama of 3 April 1973 shook all of West Africa’s fans and rockers.4