Figure 1.1. Aerial view of Double Ditch Village, a site occupied by the Mandans for nearly three hundred years, on the east bank of the Missouri River just north of modern-day Bismarck, North Dakota.

ONE

Migrations: The Making of the Mandan People

DOUBLE DITCH STATE HISTORIC SITE, AUGUST 4, 2002

Double Ditch Village is desolate, windy, and magnificent. Perched on a grassy plain overlooking the Missouri River from the east, it is the kind of historic site I like best. It has no reconstructions and little interpretation beyond a few state-funded signposts. This unleashes the imagination in ways that places like Colonial Williamsburg never will.

If I believed in ghosts, they would abound here. Alas, I do not. But my mind’s eye still populates the town with hazy human figures, domed earth lodges, raised drying scaffolds, and yapping dogs. I picture women in hide-covered bull boats on the river below, ferrying firewood from afar. How full of life this place was. How quiet it seems now.

The Ruptare Mandans—one group among several that made up the Mandan people—occupied Double Ditch for nearly three hundred years. Shallow basins in the soil mark the places where they built structures for their daily life. Most of the smaller depressions we see today indicate the location of cache pits, once the warehouses for thousands of bushels of corn. The larger depressions denote earth lodges. The landscape is pockmarked with these silent homes of ancient Americans. I walk among them in the blustery wind.

Double Ditch takes its name from two distinctive trenches that once served as fortifications for the Mandan settlement here. Visitors can still see these trenches today. There are mounds too—not giant edifices like those famous ones built in what is now Illinois by the people of Cahokia, but small, low-lying forms on the outskirts of the town. Like the ditches, they had defensive purposes, perhaps sheltering Mandan warriors as they fended off attacks by the Sioux.

For an hour or so, I am alone among the lumps and depressions in the uneven field. Then a motorcyclist pulls into the looped parking area and doffs his helmet. I wave to him, and we wander together over the town site, wondering, speculating, and imagining out loud. He is a local, rides a BMW, and likes to visit Double Ditch on his outings. I admire his bike when we return to the parking lot. He straddles the seat and extends his hand. “Thanks for visiting North Dakota,” he says. Then he starts the engine and leaves. I do the same a few minutes later, crunching across the gravel in my rented car and turning left on Highway 1804.

Behind me, Double Ditch reverts to the wind and the gophers. I have no idea that just a few weeks earlier, archaeologists had made stunning discoveries about the empty town and its history.1

THE BEGINNING

Geography shaped every aspect of Mandan existence. It is a key component of the two Mandan creation stories. The first, a story of migration, tells of ancestral Mandans emerging from the earth at the mouth of the Mississippi River. They bring corn with them, and their chief, Good Furred Robe, bears the spiritual gift of “Corn Medicine.” Like all Mandans, Good Furred Robe derives his power from the bundles of sacred objects he owns. His particular bundles give him the right to teach others how to grow maize, and thanks to his efforts the Mandan forebears become accomplished farmers.2*

Migrations follow. Good Furred Robe and his companions travel north, up the Mississippi River. They come to the point where the Missouri enters the Mississippi from the northwest, but instead of following the Missouri, they continue upstream on the Mississippi, more or less straight north, pausing each year to plant and harvest corn. When they reach a land of “fine evergreen trees,” they learn to make bows and arrows and to set rawhide-loop snares in deer trails. Soon they have ample meat to eat with their maize.3

In time, they turn away from the Mississippi, now moving southwest and stopping near the southwestern corner of present-day Minnesota. Here Good Furred Robe carves a pipe from the soft red rock they find there. But when he offers it to his people, they shun it for their traditional black ones, saying, “We are afraid of it because it is the color of human blood.” Today, archaeologists find red catlinite pipes at ancestral Mandan sites only rarely, instead finding them mostly in areas where the Mandans lived in later centuries.4

While one group stays at the pipestone quarries, another ventures northwest, making camps along the Red River and its tributaries. The lure of bison draws the ancestral Mandans still farther westward from these locations. Eventually, they each come to the Missouri River at the point where the Heart River flows into it from the west, the two bands converging to plant their corn in the rich black soil of the bottomlands there.5

As recently as 1948, it was said that the Mandan corn bundle contained the skulls of Good Furred Robe and his brothers.6

The second creation story is equally attentive to geography, but instead of sprawling over the terrain like the first tale, it explains how that terrain came about.7

First Creator makes Lone Man, the story says, when the earth is still nothing but water. Lone Man walks across the waves for a long time. “Who am I? Where did I come from?” he wonders. Turning around, he follows his own tracks backward to find out.8

On the way, Lone Man encounters his mother in the form of a red flower. He also meets a duck. “You are diving so well,” he says to the duck, “why do you not dive down and bring up some soil for me?” The bird does so, and Lone Man scatters the earth about so there is land, albeit desolate land without any grass on it.9

Then Lone Man encounters First Creator, a person like himself. The two men argue until First Creator proves that he is older than Lone Man—in fact is his father. Dispute resolved, they decide to improve the countryside around them. From the Heart River confluence, Lone Man goes north and east, creating flat grasslands with lovely lakes, spots of timber, and many animals. First Creator goes south and west, making rugged badlands with streams, hills, and herds of bison.10

Returning to the Heart River, they make medicine pipes together. This would henceforth be “the heart—the center of the world,” First Creator said.11

Finally, they make women and men to populate the land.

RUGBY, NORTH DAKOTA, AUGUST—“MOON OF THE RIPE PLUMS”—200212

The women and men who lived at the heart of the world surely knew the first thing I learn when I visit Rugby, North Dakota, on August 6, 2002: The weather here can change wildly from hour to hour. In the morning, the temperature approaches 90 degrees Fahrenheit. But later in the day, my shorts and tank top do not even begin to keep me warm. I add fleece and a windbreaker, yet the wind cuts right through, spitting tiny drops of rain. In my subjective judgment, it is freezing.

I have come to the town of Rugby on a quest both silly and compelling. My destination is a twenty-five-foot obelisk of stacked rocks beside the Cornerstone Café there. A sign pronounces the monument’s significance in white letters against a brown background: GEOGRAPHICAL CENTER OF NORTH AMERICA, RUGBY, ND.

On the one hand, I am enthralled. How cool is this? On the other hand, I am embarrassed, just as I was years ago when I planted myself in four states at once at the more famous Four Corners location, more than a thousand miles southwest of here. The center of the continent, I think to myself. Who knew it was practically in Canada?

The Heart River’s confluence with the Missouri is 120 miles southwest, just beyond the hundredth meridian, touted by experts as the western limit of nonirrigated agriculture in North America.13 Whether or not this is the heart of the world, it is surely the heart of the continent. I marvel that I’ve never been to this place before, that I’ve never contemplated its meaning and implications.

The little obelisk in Rugby centers my mental map of the continent, but the physical feature that centers my geography is the Missouri River. Again and again I come back to it, driving two-lane roads along its banks, admiring its geological handiwork, and seeking the widely spaced bridges that offer easy crossing. The Missouri is North America’s longest waterway, draining more than half a million square miles through tumbling falls and lazy, looping oxbows.

The river seems steadfast, permanent, and reliable, but it is not. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who followed the Missouri upstream and back on their 1804–1806 expedition to the Pacific Ocean, marveled at its ever-changing currents and course. As they hastened downriver in August 1806, the men found that the waters they had traveled just two years earlier were barely recognizable. “I observe a great alteration in the Corrent course and appearance of this pt. of the Missouri,” wrote Clark below the Cannonball River confluence, in the section that spans the present North Dakota–South Dakota border. “In places where there was Sand bars in the fall of 1804 at this time the main Current passes, and where the current then passed is now a Sand bar.” Some familiar shoals had become islands: “Sand bars which were then naked are now covered with willow several feet high.” Even “the enteranc of Some of the Rivers & Creeks” had changed thanks to giant deposits of mud.14

Clark was a keen observer. The multifaceted Missouri—its course, its currents, its banks, its burden of silt, its appearance—shifted constantly. But it seems doubtful that even the geologically savvy Clark could have imagined the most dramatic change of all: The waters that fed the Missouri had once flowed northeast into Hudson Bay, not south toward the Gulf of Mexico.

The Yellowstone, the Little Missouri, the Knife, the Heart, the Cannonball, the James, the Cheyenne—today all these streams run into the Missouri, converging, at least where dams do not block the way, in a growing rush as the river approaches the Mississippi at St. Louis. But this was not the case before Pleistocene ice sheets rerouted the waters. Some 1.5 million years ago, before the ice sheets crept southward, all these streams flowed toward Canada, coming together to form an ancient waterway that emptied into Hudson Bay. Its remnants survive today as Lake Winnipeg and the Saskatchewan and Nelson rivers, little known to most Americans, but of great importance in the historical geography of Canada.15

Then came the glaciers. They ground their way southward for two thousand years, advancing and retreating incrementally. At their peak, perhaps eighteen thousand years ago, they extended into the northern parts of what is now the United States. In North Dakota, only the southwestern corner of the state remained free of ice. The great Pleistocene ice sheets covered everything in their path, blocking the northward flow of the ancient tributary streams. The water ran the only way it could, turning southward and forming the changeable river that William Clark wondered at in 1806. The thirty-six-year-old explorer could hardly have known what had come before.16

ON THE MISSOURI RIVER, 1000 C.E.

Ancestral Mandans appeared in what is now South Dakota around 1000 C.E.17 Their arrival in the Missouri River valley coincided with a major climatic shift: a trend toward warmer, wetter conditions in the years from 900 to 1250. The trend extended far beyond the grasslands of North America. In Europe, these centuries coincide with the Medieval Warm Period, an era in which painters depicted bountiful harvest feasts, Norse settlers built colonies in Greenland and America, and peasants expanded their fields onto lands formerly too cold, high, or dry to plant crops.18

The ancestral Mandans were of a piece with those European peasants. Where the women of the Missouri tilled their gardens with hoes fashioned from animal shoulder blades, the commoners of Europe had the advantage of iron hoes, plows, and draft animals. But the plains villagers had an advantage of their own: They had settled in a location of stunning ecological diversity. The rich, alluvial river bottoms can be thought of as extensions of eastern deciduous forest in the midst of the western grasslands. And the adjoining steppe was one of the greatest hunting ranges in the world.19

SOUTH DAKOTA, KANSAS, AND NEBRASKA, 1250

The warm, wet conditions that drew the Mandans’ forebears to the Missouri River valley came to an end when a new weather pattern emerged around 1250. The change, which was piecemeal, was part of another global climate shift. In Europe, where the new era has come to be called the Little Ice Age, a pattern of cooler, less predictable weather settled in. On the North American plains, conditions may likewise have become less predictable, but the real marker of change was less rainfall, which put the horticultural lifeway to the test.20

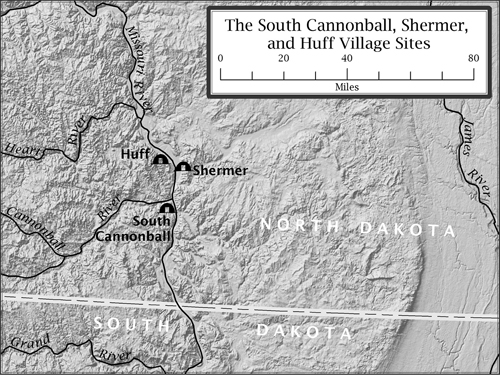

Map 1.1

The upper-Missouri settlers adapted as best they could. When harvests dwindled, they turned to wild plants to fill the void. Seeds of edible species such as dock, marsh elder, bulrush, and wild grasses all appear in archaeological remains from this period. So too do vestiges of wild fruits, which may have taken on new importance in arid conditions. Ancestral Mandans also adapted by migrating. Some headed north. Those who had built homes on far-flung feeder streams retreated to the Missouri River valley. With headwaters in the snowcapped peaks of what are now the states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, the Missouri was fed by more than parched grassland tributaries. Its water levels fluctuated, but so long as winter snows fell in the Rockies, the river persisted, even when rains failed on the plains. The Missouri offered another advantage as well: Capillary action in the adjacent grounds drew its water upward through the soil, providing irrigation from below. Crops grown in the river bottom could survive shortfalls of rain that might have desiccated plants elsewhere.21

As settlements contracted back to the Missouri River, and as the settlers adapted to reduced rainfall, they apparently came into competition with one another. They may even have come to blows, with one group or village attacking another in the quest for food. Several South Dakota village sites show signs of violent clashes as the dry era got under way. Archaeological evidence leaves the identity of the attackers uncertain. But one scholar suggests that as drought conditions worsened in the years before 1300, “individual communities” of ancestral Mandans may have “sometimes attacked each other.”22

Kindred neighbors were not the only competition these townspeople faced. The warm, wet weather that had first attracted them to the Missouri River had also enticed a different group of settler-farmers to establish themselves farther south, in the central plains region of present-day Kansas and Nebraska, beside what is now called the Republican River. These people were the forebears of the tribes later known as the Pawnees and Arikaras. By tracing the roots of the languages spoken by these peoples today, experts have determined that the inhabitants of the Republican valley were unrelated to the townspeople of the Missouri valley.* The ancestral Pawnees and Arikaras spoke a Caddoan language, named for the modern-day Caddo people, while the ancestral Mandans spoke a Siouan language, named for the modern-day Sioux, or Lakota, people. But linguistic differences did not change the most basic reality: Both groups were horticulturalists, and both depended on rainfall to bring their gardens to life.23

The climatic shift that began around 1250 left its mark on many other peoples, too, including Anasazis in the Southwest and Cahokians along the Mississippi valley. And eventually it turned the central plains into a dust bowl. Many of the Caddoans therefore abandoned the Republican River and moved north to the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota, where conditions were less severe. And here these ancestors of the Arikaras encountered the ancestors of the Mandans.24

The archaeological record gives us glimpses of what followed. For one thing, there was a great exchange of material goods, so that by 1300 few significant differences existed between the architecture, pottery, tools, and weapons of the northern farmers and those of the new arrivals from the south. In their material culture, the two traditions effectively coalesced into one.25

Yet the arrival of the Caddoan strangers had heightened the competition for resources in sparse years. One consequence may well have been violence.26

CROW CREEK VILLAGE, SOUTH DAKOTA, MID-1400s

The site of this ancient village overlooks the Missouri River in south-central South Dakota, eleven miles north of the modern town of Chamberlain. The land today belongs to the Crow Creek Sioux, but during much of the 1300s and 1400s its occupants were Caddoan-speaking newcomers—refugees or descendants of refugees from the drought on the central plains. And at some point in the mid-fifteenth century, something terrible happened here.*

The community was fortified by location and design. Naturally protected by the river and two smaller waterways, the town also had defenses constructed by its residents. Keen eyes still can discern the low-lying trace of two dry moats the townspeople dug for protection. The inner moat was bastioned and backed up with a palisade. The outer moat may not have had a palisade, but its ten bastions are still visible if you follow its course across the ground. At one time, this trench was six feet deep and twelve or more feet wide.27

These concentric fortifications indicate that the community went through a period of growth. Archaeologists think the settlers created the inner ditch and its palisade first. But twelve house sites in the gap between the two trenches suggest that the population eventually became too big to fit inside the first ditch. When this happened, residents dug the second one beyond it, enlarging the fortified area of their village. One calculation puts the town’s population at 831.28

The defense system clearly indicates that Crow Creek’s residents felt threatened from outside. And indeed they must have been, because at some point their town came under attack. The identity of the assailants is not known, but their actions were ferocious. In 1978, archaeologists unearthed at least 486 jumbled sets of human remains from the northwest end of the outer fortification ditch. If the ancient town’s population was 831, those bones represented the remains of nearly 60 percent of its residents.29 The end has to have been gruesome. Mutilated craniums indicate that the attackers scalped 90 percent of their victims and dealt skull-fracturing blows to 40 percent. They decapitated nearly one-quarter. A number of townspeople had limbs hacked off. Cut marks on jawbones indicate that some had their tongues cut from their mouths.*

If the remains in the trench represent 60 percent of the Crow Creek population, what became of the rest? Some may have lost their lives elsewhere. Women and children may have faced captivity. And some almost certainly escaped.30

It seems likely that a few escapees eventually made their way back to the destroyed town to tend to the remains that lay there. Whoever placed the bodies in the ditch did so with care, covering them with hard-packed clay to deter erosion and scavenging animals. In the soil just above the burials, archaeologists found the bison scapula hoes that surviving townspeople must have used to bury their friends and relations.31

The remains of the slaughtered villagers lay undisturbed for five and a half centuries until the combined forces of erosion, vandalism, and archaeological inquiry brought them to light in the 1970s. Were the attackers ancestral Mandans? Quite possibly, but the truth is that no one knows.32

Whoever the assailants at Crow Creek were, two things are clear: first, fortified villages became common in the area after 1300, their construction correlating with episodes of drought; and second, by the time of European contact some centuries later, the Mandans and Arikaras—respective descendants of the Siouan- and Caddoan-speaking groups—had long had troubled relations. The disaster at Crow Creek may be early evidence of a pattern of dispute between them that went on for centuries.33

THE CANNONBALL RIVER

The Cannonball River starts in Theodore Roosevelt country—at the edge of the North Dakota badlands where, in the 1880s, the Harvard-trained politician found solace and manhood after personal tragedy sent him reeling. From here, the stream flows east across 150 miles of treeless plains and enters the Missouri not far above the South Dakota border. The confluence is today obscured by the waters of Lake Oahe, but there was a time when that confluence intrigued nearly every Missouri River traveler. Scattered along the shoreline and protruding from the banks were hundreds of stone balls, some as big as two feet in diameter.

These stone balls are the product of the ancient Fox Hills and Cannonball sandstone formations, deposited by inland seas that inundated the landscape for nearly half a billion years. Seventy million years ago, continental uplift caused the waters to recede and the sea floor to emerge, visible today as undulating plain. By slicing through this surface to expose the layers of sediment below, the Cannonball River revealed the land’s ancient, hard-to-fathom aquatic history. The Fox Hills and Cannonball strata are rich in minerals, especially calcium carbonate—a vestige of marine animals such as crabs, which often appear fossilized in these formations. When groundwater flows through the sandstone, the calcium crystallizes with other minerals and forms concretions—literally concrete—of a spherical shape.34

William Clark, who examined the mouth of the Cannonball as he and Meriwether Lewis headed up the Missouri River on October 18, 1804, noted that the balls were “of excellent grit for Grindstons.” His men selected one “to answer for an anker.” The German prince Maximilian of Wied viewed the distinctive globes from the deck of a steamboat in June 1833. The Cannonball River “got its name,” he explained, from the “round, yellow sandstone balls” along its shoreline and that of the Missouri nearby. They were “perfectly regularly formed, of various sizes: some with a diameter of several feet, but most of them smaller.” Today, they are little more than a curiosity. Local residents use them as lawn ornaments.35

AT THE CONFLUENCE OF THE CANNONBALL AND MISSOURI RIVERS, 1300

For ancestral Mandans, the migration farther north and the construction of new towns may have mitigated the threat of violence. Though they fortified some of their new settlements, they built others in the open, unfortified pattern of old, with fourteen to forty-five lodges spread over as many as seventeen acres.36 One such town sat on the south bank of the Cannonball River where it joins the Missouri, in what is now the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

The South Cannonball villagers tapped a wide array of food resources. In the short-grass prairies to their west, herds of bison beckoned hunters. In the mixed- and tall-grass lands across the Missouri to the east, antelope, deer, and small game did the same. The riverbanks brimmed with seasonal choke-cherries, buffalo berries, serviceberries, raspberries, plums, and grapes, while river-bottom gardens produced a bounty of maize, beans, squash, and sunflowers. The Missouri itself offered catfish, bass, mussels, turtles, waterfowl, and drowned “float” bison, this last considered particularly delectable.37

Much of the South Cannonball village site has succumbed to the steel plows of more recent farmers tilling the soil here, but the layout of the ancient village is clear. The settlers dispersed their town over fifteen acres, with ample space between individual homes. The houses themselves, about forty in number, were nearly rectangular log-and-earth structures, narrower at the rear and wider at the front.38

There were no fortifications. It appears that the occupants of the South Cannonball hamlet counted on peaceful relations with neighboring villagers and with the hunter-gatherers who may have visited from time to time.39 But fortified towns nearby suggest that security was tenuous. South Cannonball may have been one of the last villages to follow the scattered settlement pattern of earlier days. By the mid-1400s, the same neighborhood was home to some of the most massively defended sites ever seen on the upper Missouri River.

HUFF VILLAGE, 1450

Fortifications were just one marker of heightened anxieties. The Mandan forebears began building their homes closer together; they gathered in larger numbers, so population densities increased; and they kept moving upstream. They consolidated in present-day North Dakota, leaving what is now South Dakota to the Caddoans and their Arikara descendants. As the Middle Ages gave way to early modernity on the far side of the Atlantic, so too the upper-Missouri people took on their modern identity as the Numakaki, or Mandan. Numakaki was the name by which Mandans referred to themselves until the late 1830s.*

At a location known as Huff, Mandans built a large settlement that displayed many of the adaptations they were making in the fifteenth century. Most of the town site still survives, preserved for visitors who follow Highway 1806 south for twenty miles from Mandan, North Dakota. The waters of the Missouri River have been stilled here by the Oahe Dam, a 1950s construction that created an enormous lake whose waters lap away at the northeastern edge of this now-silent village. The Mandans appear to have occupied the place for only a generation, but it must have buzzed with activity during those short years. The town comprised 115 large homes and more than a thousand residents. At an average density of 104 citizens per acre, the place was jam-packed. In its size and amenities, the settlement was comparable to a European market town of the same era.40

Its fortifications were formidable. The Missouri River protected Huff’s northeast flank, and a dry moat surrounded the other three sides of the town. The women who dug the moat threw the dirt on the inside bank, raising it several feet. Here, a menacing abatis of sharpened stakes angled outward from the embankment; higher still, a log palisade reached skyward. The palisade and entrenchments had an additional feature: bastions—ten in all—protruding outward every two hundred feet or so. These bulwarks offered superior fighting angles for warriors defending their town.41

Inside the walls, meandering rows of homes ran more or less parallel to the Missouri River. These sturdy, semirectangular affairs, also constructed by women, were positioned shotgun-style along well-worn footpaths. As in any modern town, the houses varied in size, but by European standards they were large: The ceremonial lodge that faced the town plaza was nearly seventy feet long and forty feet wide; residential structures, with log frames and A-shaped roofs, had more modest dimensions, perhaps fifty by thirty-five feet. Their builders banked the exterior walls with earth and sod.42

Map 1.2

With its fortifications, sturdy homes, and large, closely packed populace, Huff typified a Mandan village of the mid-fifteenth century. Other communities sprang up north and south of Huff on both sides of the Missouri River, and some remain to be excavated by future investigators bringing new technologies and fresh insights to the American past. But at least one site already stands out for the features it shares with Huff. Across the river and just a few miles south, the settlement known as Shermer, which probably predated Huff by a few years, had many similar features—lots of people, bastioned defenses, and rectangular houses in meandering rows.43

According to early-twentieth-century informants, the residents of Shermer had a rich spiritual life, performing rites “connected with the sacred cedar and open section of the village.” Such reports suggest that the town had a ceremonial plaza with a classic Mandan shrine consisting of a little picket of vertical planks around a sacred cedar post. Unfortunately, recent cultivation and road-building have made it impossible to see where these features might have been. But it is likely that they enabled Shermer’s residents to perform the cardinal ceremony of Mandan life—an elaborate, multiday event called the Okipa. Indeed, the Mandans called Shermer “Village Where Turtle Went Back,” a name arising from the ancient story of how they acquired the sacred “turtle drums” used in the ceremony. Centuries after the Mandans stopped living on this site, they continued to visit to perform special rituals, doing so as recently as 1929.44

The fifteenth century, then, was a period of consolidation, as towns like Huff became bigger and more crowded than ever.45 Mandans used consolidation repeatedly to build and retain their influence and security. Whatever the outside threats may have been, the concentration of people made their communities pivot points of life on the northern plains.

ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1450

Far from the open country where the Mandans lived, someone on the northwest coast of North America picked up a seashell. It could have been anyone—male, female, Tlingit, Haida, Coast Salish, or a member of some other tribe. We do not know whom, and we do not know when. Perhaps it was 1450. Perhaps it was earlier or later.

We do know about the shell. It belonged to a little marine mollusk called Dentalium, favored as a medium of exchange among the peoples who lived in the Pacific Northwest. For its type, the shell was long, nearly four centimeters from end to end, with a hollow space once occupied by the living creature that had made the shell its home.46

We also know about the shell’s fate. Somehow it ended up in Huff, where archaeologists found it and three others like it in 1960. The diminutive size of these relics might make them easy to dismiss, but they embody something very large: the remarkable reach of Mandan commerce. Investigators at sites on the northern plains have unearthed items traceable not just to the Pacific Northwest but also to Florida, the Tennessee River, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard.47

Shells, beads, ceramics, and jewelry are the sorts of ancient trade goods that survive best over time. They may weather and degrade, but they do not rot, and they hold little appeal to scavenging animals. Archaeological finds that include these shells thus may not accurately represent the full content or volume of early trade. If the documented commerce of the historical era is any reflection of earlier times, most premodern Mandan transactions involved not the durable objects that turn up in modern-day excavations but perishable items, especially foodstuffs, that rapidly rot and disappear if not eaten by people or other animals.48

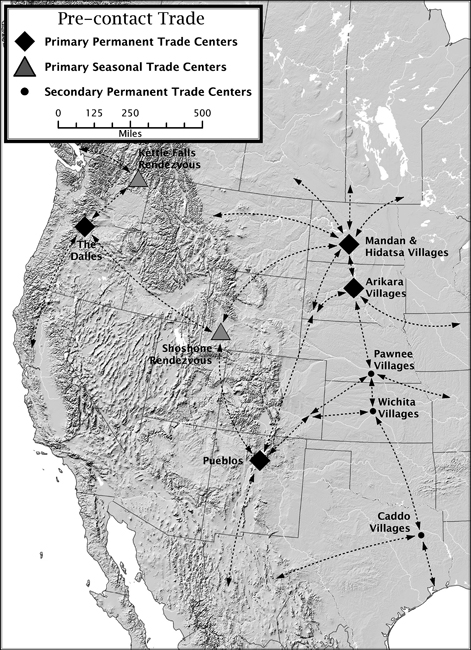

Map 1.3

In any event, we know that the villagers actively cultivated trade. Exchanges of children and intermarriage with outsiders allowed commerce to follow far-flung kinship lines. So too did the Mandan adoption of captives taken in war. Of course, these same practices diminished language barriers, and multilingual Mandans and their adopted kin became adept at translation.* On the rare occasions when linguistic obstacles arose, the villagers turned to what scholars today call plains sign talk, “one of the most effective means of nonverbal communication ever devised.” One eyewitness in the early nineteenth century found it “surprising how dextrous” the Mandans and their neighbors were at “communicating their ideas by signs. They will hold conference for several hours together and upon different subjects and during the whole time not one single word would be pronounced upon either side, and still they appear to comprehend each other perfectly well.” Another practice also encouraged commerce: The villagers declared the space inside town walls a neutral zone in which any visitor, even an enemy, could expect hospitable treatment.49 The result was a steady flow of people and goods through the upper-Missouri settlements.

Figure 1.2. The Hidatsa sign talker Horn Weasel speaking in plains sign language at Fort Belknap, Montana, circa 1905.

Commerce did not mean sustained amity, however. Strongholds like Huff express danger as well as eminence. The massive, bastioned fortifications suggest that the people of Huff were subject to direct assaults by hundreds of shield-bearing warriors. Long before Europeans reached the upper Missouri River, the interdependent peoples of the northern plains lived in a state of perpetual tension, sometimes trading, sometimes raiding to meet their needs.50

THE KNIFE RIVER CONFLUENCE, 1450

The Hidatsas—or at least the people who became the Hidatsas—arrived on the upper Missouri River after the Mandans were already settled there. The story of their arrival has several versions, which vary of course with different informants, different subgroups of the Hidatsa people, and different interpretations by archaeologists and anthropologists.51 And the Mandans themselves have their own recollection of their northerly neighbors’ arrival.

The gist of the Hidatsa story is this: Decades before Christopher Columbus set out on his own westerly journey, three groups of westward-migrating ancestors converged on the confluence of the Knife and Missouri rivers. First came the Awatixas, who prospered in earth-covered longhouses beside the Missouri River some forty or fifty miles above the Mandan settlements. By 1450, there were eight to ten thousand of them (a figure comparable to the population of the same area in 2005). The Awatixa population soon collapsed dramatically, however, possibly because of drought, warfare, or new infectious diseases. But before long two other Hidatsa groups, the Awaxawis and the Hidatsas proper, bolstered the Awatixa numbers. Both groups came from Devil’s Lake—really a chain of glacial lakes—in what is now eastern North Dakota. They initially built their towns near the Mandans, but eventually most of them joined the Awatixas upstream at the Knife River.52

Two of these three groups were experts at corn cultivation. The Hidatsas proper were the exception. At one time, they had planted maize at Devil’s Lake, but they lost knowledge of this art during a brief stint in the moose country of the Great Lakes. The Mandans retaught them when they arrived at the upper Missouri.53 In 1913, an elderly Hidatsa woman named Buffalo Bird Woman related the story as her grandmother had told it to her:

A Hidatsa war party reached the east bank of the river and spotted Mandans on the far side, she said. Neither group dared cross, each “fearing the other might be enemies.” After a while, the Mandans broke up some parched ears of corn and “stuck the pieces on the points of arrows” and shot them to the other bank. “‘Eat!’ they called.” The Hidatsas did, understanding perfectly since both groups spoke Siouan languages and used the same word for “eat.” The Hidatsa warriors went home and told their village what had happened. Soon thereafter, the village sent a delegation to the Mandans, who responded by breaking an ear of corn in two and giving “half to the Hidatsas for seed.” They carried it home, “and soon every family in the village was planting corn.”54

THE HEART RIVER CONFLUENCE, 1500

By 1500, when Spanish sailors were groping their way around the Caribbean Sea and enslaving native Tainos to pan for gold, Mandan settlers were likewise on the move, consolidating northward yet again in a cluster of towns centered on the confluence of the Heart and Missouri rivers. Archaeologists have identified as many as twenty-one nearby settlements that were occupied between 1500 and 1750, at least six of which we now think of as “traditional” Mandan towns—large, fortified villages inhabited until the late eighteenth century.55 Stockades and ditches protected each one. The peaceful Tainos confronting the Spanish in the Caribbean might have taken a lesson from the defensive measures of these upper-Missouri farmers.

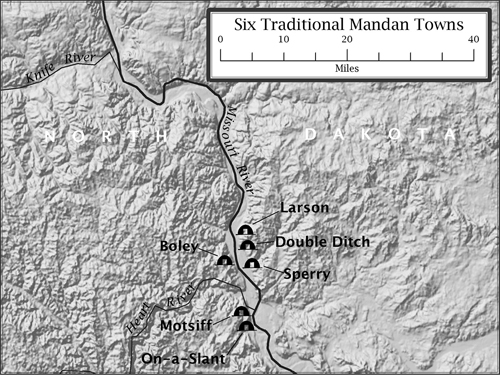

Map 1.4

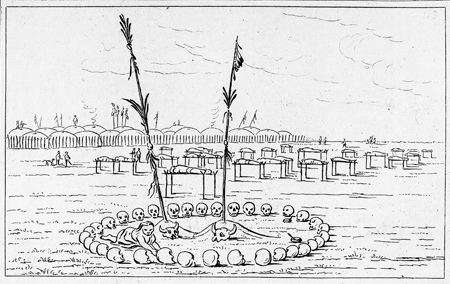

Figure 1.3. Mandan Village, Back View and Cemetery, drawing by George Catlin, 1832.

The Mandans were now at the center of northern plains life. Even as they mingled with Hidatsas and other peoples, the villagers confirmed their own distinctive traits, stories, and rituals: They planted corn, they hunted bison, and they trafficked in goods with all comers. They also built one ceremonial plaza per town, each marked by a shrine that invoked Lone Man and reminded everyone of the sacred Okipa rites.56

Beyond the open plaza, a typical village was a jumble of construction. Earth lodges at this time could have been rectangular or round, but fashion trended to the latter, ranging from twenty to sixty feet in diameter. A large settlement might contain one hundred and fifty or more.57 Between the lodges were wooden drying stages, laden in the harvest season with skewers of sliced squash and with thousands of ears of corn, sometimes loose, sometimes braided into ropes. These drying stages gave the towns a cluttered appearance, but because they stood more than six feet above the ground, they posed no obstacle to foot traffic. Outside the town walls, family gardens ran for miles along the river, the acreage under cultivation depending on population size, horticultural skill, and the Mandans’ growing preference for planting over hunting.58

How many people lived in these towns when they were founded? The truth is that we don’t know. Determining the size of indigenous populations before contact with Europeans has been one of the most vexing problems confronting American historians, and in this regard the Mandans are no exception.59 But archaeology in Mandan country has proceeded by leaps and bounds in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and although it has not yet produced answers, it has produced clues.

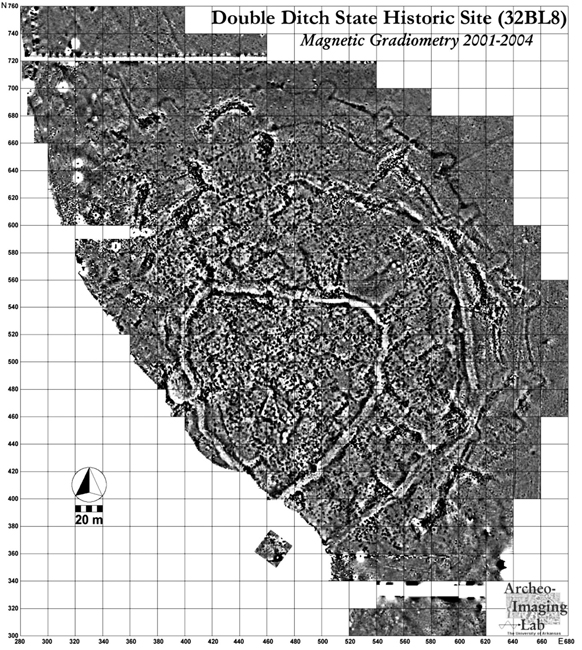

From 2001 to 2004, a talented crew of archaeologists reinvigorated the study of Double Ditch Village, where investigations had languished for many years. The team included Stanley Ahler, Kenneth Kvamme, Paul Picha, Fern Swenson, and Raymond Wood, all with far-reaching archaeological experience along the upper Missouri River. Some of their methods, such as coring and excavating, were intrusive, but the most stunning information came from newer, nonintrusive methods that left the landscape undisturbed.60

Using thermal imaging, ground-penetrating radar, magnetic gradiometry, and electrical resistivity, Kenneth Kvamme generated digitally enhanced maps of the once-thriving Mandan settlement. The maps he created in the summer of 2002 caused scholars to do a double take on Double Ditch. The site name derives from the two clearly visible fortification ditches that once protected the town. But the new survey methods revealed what was not apparent to the naked eye: a third and then a fourth ditch outside the first two, extending the village well beyond its known boundaries. Double Ditch was really Quadruple Ditch, and the town had at some point been much bigger than scholars had once imagined. Investigators concluded that at the time of its founding, just before 1500, Double Ditch had a peak population of two thousand.61

Their research was just beginning. In 2005, the archaeologists found that Boley Village, on the Missouri’s west bank, had its own complex of ditches that showed changing population sizes. Then they looked at a town called Larson, two and a half miles north of Double Ditch. Like its neighbor, it had two visible defensive trenches.62 But the town was not so well preserved: Erosion, plowing, and amateur hunters of old pots had taken a toll. Nevertheless, remote sensing indicated that Larson also was much larger than earlier investigators had recognized. Like Double Ditch, it had a total of four ditches, including two previously overlooked ones outside the known village boundaries.63

Double Ditch is unique in an unfortunate way. It is the only traditional Mandan village the remains of which are largely intact in the early twenty-first century. It thus provides a sort of baseline for population estimates elsewhere. If Double Ditch alone contained two thousand people at its pinnacle in the early to mid-1500s, how many Mandans were there in all at that time?

Archaeologists have identified at least twenty additional Heart River–area settlements occupied after 1500. Few had the size or longevity of Double Ditch; some had multiple occupations, and some may have been inhabited for only a few years. Some may even have been Hidatsa or mixed Mandan-Hidatsa communities. For these and other reasons, firm numbers are hard to pin down, but given the size of Double Ditch, it seems likely that the overall population was large. Surely there were ten thousand Mandans in the sixteenth century. Twelve thousand may be closer to the mark. But numbers as high as fifteen or twenty thousand also seem possible.64

For now, one thing is clear: When Spanish conquistadors launched their early forays into lands far to the south of here, the upper Missouri River valley was teeming with people.

Figure 1.4. Magnetic gradiometry of Double Ditch showing a total of four fortification trenches, the outer two being invisible to the naked eye. This high-tech imaging, from the first decade of the twenty-first century, revealed them for the first time in centuries.

DOUBLE DITCH AND LARSON IN THE LATE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

Something happened in the late 1500s that caused the populations of Double Ditch and Larson to collapse. The story’s faint outlines appear in those receding fortification rings around the villages.

The change can be seen most clearly at Double Ditch. The founders built the outermost ditch—ditch 4—to protect a population of roughly two thousand. But in the mid- to late 1500s, the townspeople drew inward and dug a new trench—ditch 3—for defense. They soon abandoned this ditch too, retreating to the confines of an even smaller fosse now known as ditch 2, the outermost of the ditches visible to us today. The sequential contractions represented a 20 percent reduction in the area of the town by 1600.65

At nearby Larson, erosion, road-building, and other forces have destroyed much of the archaeological record, but surviving evidence suggests that similar shrinkage—literally retrenchment—occurred here too. In the late 1500s, the citizens of Larson withdrew from their outermost fortification ditch and then from the one just inside it. Like their Double Ditch neighbors, they hunkered down inside the second of two trenches still visible today.66

What caused the collapse in numbers? Scholars have yet to venture an answer. It is conceivable that the receding defense lines do not point to calamity but instead reflect the vicissitudes of local decision-making. Village composition was fluid. Just as groups of their ancestors moved northward incrementally over the centuries before the Mandans’ settling in Double Ditch and Larson, so later groups may have calved off and moved. They might have built new towns or joined other established villages. The Boley site, on the Missouri River’s west bank, shows evidence of multiple, culturally varied occupations.67 But this scenario seems unlikely for Double Ditch and Larson. The population losses at the two sites were simultaneous and repeated, and it is difficult to imagine what might have led to successive, coordinated departures of many people from both towns. Catastrophe—in isolation or in series—seems more likely. In fact, the sixteenth century may have been an especially treacherous time to reside in North America.68

As modern-day city dwellers know well, providing clean water and handling sewage disposal efficiently pose challenges for any large, crowded settlement. Europeans learned hard lessons about these matters in medieval and early modern times. Mandan population density after 1400 appears to have been higher than that of many European towns—exceeding one hundred people per acre, as we have seen.* Such densities, writes the English historian Christopher Dyer, “inevitably created problems of disposing of effluents and rubbish.”69 If local, crowd-related problems such as these did not contribute to the collapse at Double Ditch and Larson, other environmental factors may have.

A giant drought afflicted most of North America, including Mexico, in the late 1500s. Tree-ring data give us a year-by-year view of the parched conditions, indicating they were particularly severe in the upper-Missouri region between 1574 and 1609.70 Were they severe enough to decimate Double Ditch and Larson? For now, we don’t know. But another drought-related dynamic also could have come into play: Even if the villagers had enough food for themselves, others might not have fared so well, and Mandan food stores might have brought hungry rivals down upon them. The omnipresent fortifications around villages make it clear that the Mandans had enemies in this period, and episodes like the Crow Creek massacre confirm that warfare among Missouri River peoples could result in sudden and substantial population loss. If this occurred in sixteenth-century Mandan country, mass burials and signs of violence may one day turn up at Larson or Double Ditch.

Drought can also bring on pests, especially grasshoppers. “The most severe infestations are likely to occur during seasons when the weather is hot and dry,” warn modern agricultural scientists. From the grasshopper’s perspective, successive years of drought are ideal. The insects eat almost any plant material. In the aftermath of an 1860s drought, Hidatsa women complained that grasshoppers ate “their corn plants before the kernels could form.”71

Newly arrived infectious diseases may likewise have reduced villager numbers. In the aftermath of Hernán Cortés’s smallpox-assisted conquest of the Aztecs, wave after wave of pestilence swept Mexico. The years 1531, 1532, 1538, 1545–48, 1550, 1559–60, 1563–64, 1576–80, 1587, and 1595 all witnessed epidemic outbreaks. Vague or elusive descriptions make some of these plagues hard to identify, but many were imported contagions such as influenza, measles, and smallpox, never before seen in North America.72

Could these infections have reached the center of the continent? The first European trade goods—a few glass beads and iron items—reached the Mandans around 1600.73 The timing converges closely with the population collapse at Double Ditch and Larson. If novel trade goods made their way to the Mandans by 1600, novel infections could have done the same. Indeed, the waves of pestilence rolling out of Mexico and other points of European contact might have moved even faster than more tangible commodities. If this is the case, the receding fortification lines at Double Ditch and Larson suggest both the vitality of indigenous networks and the deadly effect of imported diseases.

UPPER-MISSOURI VILLAGES, 1600

Pestilence aside, the arrival of new items of trade on the upper Missouri is noteworthy in its own right. Historical reference points put the timing of this development in perspective. By 1600, a scant century had passed since Christopher Columbus’s Caribbean landfall. England’s “lost colonists” had come to Roanoke and disappeared, and the enduring colony at Jamestown in Virginia was not yet established. The Pilgrims did not get to Plymouth Plantation until 1620. On the St. Lawrence River, the French did not found Quebec until 1608, the same year that the Spanish established Santa Fe. Indeed, in 1600 the only permanent European colony north of Mexico was St. Augustine, Florida, built by Spanish settlers in 1565.

The European colonization of North America had barely begun. But Native American commerce and communication patterns extended the reach and amplified the effect of the paltry Old World presence. Even as the newcomers struggled to keep their plantations going, their trappings coursed across the continent.

NEW TOWN, NORTH DAKOTA, MONDAY, AUGUST 2, 2004

It is dawn. I am on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, pedaling my bicycle furiously to stay warm on Highway 23 between Parshall and New Town, North Dakota. As the sky brightens at my back, a full moon clings to the horizon in front of me. A lark sparrow sings loudly. A few miles later, I pass a black-and-white magpie poking bravely at roadkill as scores of cyclists roll past. The prairie around me is the official homeland of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations, the Three Affiliated Tribes.

It is the second day of an organized, weeklong bike ride called CANDISC, an awkward acronym for Cycling Around North Dakota in Sakakawea Country. The ride covers more than 450 miles of prairies and badlands. My companions, some five hundred in all, are an eclectic bunch. Some are college kids, ready to party when we roll into each night’s campsite. Some are serious cyclists, treating this as a training ride to build long-term endurance. Others are parents and barely adolescent children, embarking on inexpensive “bonding” vacations. And there are couples, some of whom do a long bike trip each summer. I am surprised to find that at forty-four years, I am younger than most of my fellow riders. But despite our differences, we are largely a white, middle-class crew.

Our route takes us in a giant loop along the Missouri River, first heading west along the waterway’s north bank to the Montana border, and then east along the south bank to return. Today’s ride—one hundred miles—is the longest. I am grateful for the cool morning and for a weather forecast that promises temperatures only in the eighties.

Twenty-four miles of highway separate Parshall from New Town, where breakfast beckons. Near the midpoint of this stretch, I see the placid blue water of Lake Sakakawea to my left. The lake is physically the creation of the Garrison Dam, a two-mile-long earthen barrier that stifles the flow of the Missouri River a hundred miles below New Town. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the dam in 1947–53, after the federal purchase of thousands of acres of land from the Fort Berthold Reservation for a paltry sum. In important ways, therefore, the lake is really the creation of government bureaucrats who valued hydroelectric power and the unfulfilled promise of irrigation more than Indian treaty rights. When the waters of Lake Sakakawea began rising in 1953, they flooded nine Indian communities—all Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara—out of their bottomland homes, disrupting life and sending the peoples of Fort Berthold into a social and cultural tailspin.74

In the early twenty-first century, New Town is the hub of reservation life. By the time I arrive there, the temperature is perfect, so I decide to skip breakfast and keep rolling. Our route takes us north and then west, off reservation land, but we are still in Indian country. As the artificial lakescape unfolds beside my path, I contemplate the history of this watercourse through the prairies. The geologic past makes my head reel. Our route skirts the edge of Pleistocene glaciation: Where I ride, there were once gigantic ice sheets; to my left, across the lake, there were none. But the relatively brief human past here, so closely tied to the bottomlands, has now been inundated. Garrison Dam did more than silence a portion of the rumbling, rushing Missouri River. It stole the places and passageways where people made their lives.75

Figure 1.5. The author on the CANDISC bike tour, August 2004.

I am grateful that downstream, in the area between Lake Oahe and Lake Sakakawea that constituted the heart of the world, some eighty miles of river remain unobstructed. Other human activities have wreaked havoc on the landscape, but where it matters most, the Missouri and its Mandan water spirits still run free.