TEN

Corn: The Fuel of Plains Commerce

CROPS ON THE UPPER MISSOURI

The reports of Lewis and Clark and other turn-of-the-century visitors to the upper Missouri give added depth to earlier accounts of Mandan commerce. They show how variables such as migrations, equine transportation, and the availability of new goods altered trade patterns, but they also show that well into the nineteenth century, one aspect of plains barter remained the same: It was mostly about food. For the Mandans and their nomadic trading partners, that meant exchanging the yield of the garden for the yield of the hunt. Corn—the produce of village women—was the Mandan lifeline. They called it kóxãte.1

As early as 1540–41, soldiers accompanying the explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had observed nomadic peoples bringing bison products to trade at the corn-growing pueblos of New Mexico.2 But the traffic of the northern interior remained unseen by outsiders for generations. One early European report was written by Pierre de la Vérendrye four years before he went to the villages. He tells us that in January 1734, when he met a band of Crees and Assiniboines at Fort St. Charles, near what is now the Minnesota-Manitoba border, he asked them to visit him again in the spring, but they told him they could not, because “as soon as spring opened,” they were traveling to the upper Missouri “to buy corn.”3 Two years later, the Jesuit father Jean Aulneau wanted to join one of these expeditions in order to evangelize among the Mandans. “I purpose … to join the Assiniboels,” he wrote, when they go “to procure their supply of corn.” But the missionary’s ambition and life both ended at the hands of the Sioux a few weeks after he penned these words.*

During his journey of 1738, La Vérendrye witnessed the maize trade for himself. Corn was the first item listed when he described the barter between Mandans and Assiniboines. The traffic in feathers, craft items, and European goods paled in comparison with that in foodstuffs. “The hunting Indians,” one scholar has observed, “valued grain more highly than they did European goods.” This may have contributed to La Vérendrye’s view that the Mandans “cheated” the corn-hungry Assiniboines, who seemed all too eager to exchange meat and manufactured items for grain.4

Eyewitness accounts fade for a half century after the La Vérendrye forays, but the corn trade continued apace. For outsiders and plains denizens alike, it was the defining characteristic of the Mandans and their towns. The explorer Jonathan Carver—the same man who fell for Pennesha Gegare’s rattlesnake yarn in 1766—never came close to the upper-Missouri settlements, but he heard stories about them while touring the Mississippi River in the late 1760s, and learned that Mandans raised “plenty of Indian corn” for purchase by Crees and Assiniboines.5

The North West Company agent Peter Pond indicated that on occasion, upper-Missouri growers even delivered grain to their trading partners. An inscription on Pond’s 1785 map notes, “Here, upon the branches of the Missury live the Maundiens, who bring to our Factory at Fort Epinett on the Assinipoil River Indian corn for sale.” Fort Epinett was also called Fort Pine, and the “Assinipoil river” is the Assiniboine River in southern Manitoba, where Pond saw the traffic in person. John Macdonnell, a North West Company trader like Pond who was familiar with both Fort Epinett and the upper Missouri, said the Mandans were “the best husbandmen in the whole North-West.” They raised “Indian Corn or (maize) Beans, Pumpkins, Squashes &c in considerable quantities; not only sufficient to supply their own wants … but also to sell and give away to all strangers that enter their villages.” And we also know of a Hudson’s Bay Company trader who sought “to visit the Mandals and Trade Horses, Indian corn and Buffalo robes” in 1796.6

When David Thompson and his men arrived in late 1797, he too reported that the villagers raised huge quantities of corn, “not only enough for themselves, but also for trade with their neighbours.” Thompson and his companions carried “away upwards of 300 pounds weight” on their northward return across the prairies. The supplies were as essential to them as to the Crees, Assiniboines, and other nomads. Thompson reported that during their trip, he and his companions “killed very few Bisons and lived as much on Corn as on Meat.”7

Accounts of the Mandan corn trade reached St. Louis in the 1790s. The schoolmaster Jean Baptiste Truteau heard about the commerce upriver when he visited the Arikaras in 1794–96, reporting on his return that the “Assiniboin, a wandering nation to the north of the Missouri,” purchased “horses, corn, and tobacco” at the Mandan and Hidatsa towns.8

The early nineteenth century brought a regular influx of St. Louis visitors northward, and these men documented the maize traffic in more detail. In 1804, the Frenchman Pierre-Antoine Tabeau noted a curious pattern in relations between the Arikara villagers and the nomadic Lakotas. Most of the year, the two parties lived “in a state of war and in mutual distrust,” but in late summer, “at the maturity of the corn,” they “made peace.” The Sioux then came “from all parts loaded with dried meat, with fat, with dressed leather, and some merchandise,” which they exchanged for the Arikaras’ “corn, tobacco, beans, and pumpkins.”9

For Lewis and Clark, who crossed paths with Tabeau in the Arikara towns, corn was a diplomatic lubricant that eased their transit upstream. When challenged by the Sioux in Nebraska and South Dakota, the Corps bought them off with corn. Then, among the Arikaras, the explorers were on the receiving end. On October 11, 1804, they accepted gifts of “a fiew bushels of Corn Beens &.c. &c.” at three different Arikara villages. The next day, they took delivery of an additional “7 bushels of Corn” and “Some Tobacco” at one village and “10 bushels of Corn, Some Beens,” and squash at another. The travelers responded with gifts of their own.10

Among the Mandans and Hidatsas, the corn traffic began on October 28, the day after the Corps of Discovery arrived. “We had Several presents from the Woman of Corn boild homney, Soft Corn &c. &c.,” Clark wrote, and thereafter it was constant. “Will you be So good as to go to the Village,” requested an Indian messenger on October 30; “the Grand Chief will Speek & give Some Corn.” He advised the newcomers to “take bags” along. The next day, at Black Cat’s Ruptare Mandan town on the east side of the river, Clark took delivery of “about 12 bushels of Corn which was brought and put before” him “by the womin of the Village.”11

And thus it went for the duration of the winter: Eleven bushels on November 2. “Several roles of parched meal” on November 11. Buffalo robes and corn on November 16. More corn on December 21. Still more on December 22. And “great numbers of indians … bringing Corn to trade” on December 23. More corn taken in “for payment” on December 30. On January 1, 1805, “13 Strings of Corn” came in. January 15 brought several women “loaded with corn,” and January 21 brought in “considerable Corn.” The first day of February yielded “Some Corn” from a Hidatsa “war Chief.”12

All this corn changed hands either by barter or by gift exchange. In February, “many” natives visited the blacksmith John Shields and paid him “considerable quanty of corn” for his work.* The men of the expedition thus procured not just “Corn Sufficient for the party dureing the winter” but also “about 70 or 90 bushels to Carry” with them when they left in the spring.13

What did a bushel of maize really mean? Except for occasional “strings” of corn—fifty-four or fifty-five high-quality ears braided together by the husk—Lewis and Clark took in shelled maize, no longer on the cob.14 So when they referred to a “bushel” of corn they probably meant loose kernels, easily packed, not bulky whole ears.

How big was a bushel? In 1804, units of measure had yet to be standardized. Because of vagaries in English law, which remained the basis for American measurements, and because of the variously sized quarts and gallons that went into a bushel, at least eight different “bushels” existed. Regional traditions added to the confusion: In some places a heaping bushel was the norm; in others a level bushel prevailed. We don’t know what criteria Lewis and Clark used. But the modern standard gives us an idea of the amount of corn involved: One modern bushel equals eight gallons of capacity, and according to the Iowa Corn Growers Association, a bushel of dried, shelled maize weighs fifty-six pounds.15 So “70 or 90 bushels” was a lot of corn—two U.S. tons or more. But for villagers accustomed to supplying maize to thousands of visiting nomads each year, the grain consumed and carried away by the Corps of Discovery would have seemed less impressive than it does to us today.

Village women put intense pressure on guests to buy their produce. When the trader-explorer Alexander Henry visited the upper-Missouri settlements in July 1806, shortly before Lewis and Clark passed through on their return trip,* he readily accepted Mandan hospitality, enjoying meals of dried meat, pemmican, boiled corn, and beans. “They soon after asked us to trade,” he wrote. “They brought us Buffalo Robes, Corn, Beans, Dried Squashes &cc,” but when Henry refused, saying he only wanted “to see them and the country,” his hosts were baffled and suspicious. “They continued to plague us until it was intirely dark, when they retired very much disappointed.”16

Mandan suspicions may have been justified: Henry’s journal shows that he was obsessed with acquiring top-quality horses. And in the meantime the pressure continued. After Henry and his companions bought a few travel supplies on July 20, they “were plagued for some time after by Women and Girls, who continued to bring in bags and dishes full of their different kinds of produce, and would insist upon our trading.” It took them “some time” to get “clear of their importunities.”17 For Mandan women, guests not seeking corn were difficult to comprehend.

By the 1830s, American fur traders operating out of St. Louis had built posts on the upper Missouri, and they counted on corn acquired from the villagers for their sustenance. Everyone working on the plains did—Indians and non-Indians alike. An 1833 observer traveling down the Missouri from the Yellowstone confluence passed a boat “loaded with Indian corn” going upriver. It had left the Mandans two weeks before and was destined for a new fur-trade post.18

Archaeological discoveries help to confirm that this corn commerce was both large and long-lasting. A 1999 magnetic gradiometry survey of Huff, which the Mandans had occupied for about a generation in the mid-fifteenth century, revealed “an unexpectedly high number” of storage pits, “testifying to the volume of horticultural production.” The huge capacity of these caches, representing space for some seventy thousand bushels, “came as a complete surprise” to the archaeologists. Findings at Double Ditch were just as compelling. Using a combination of noninvasive survey techniques, archaeologists identified “thousands of subterranean corn storage pits” in the once-thriving settlement. Village occupants consumed much corn themselves, of course, and probably did not use all the storage pits at once.19 But the astonishing volume of their caches suggests the general magnitude of the Mandan corn trade.

NORTHERN PLAINS, CIRCA 1800

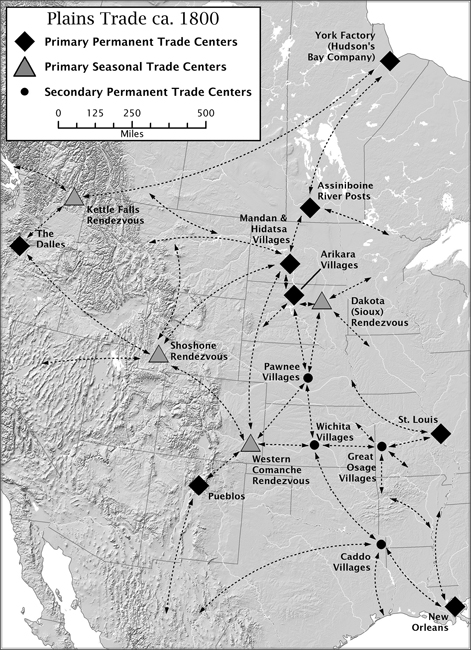

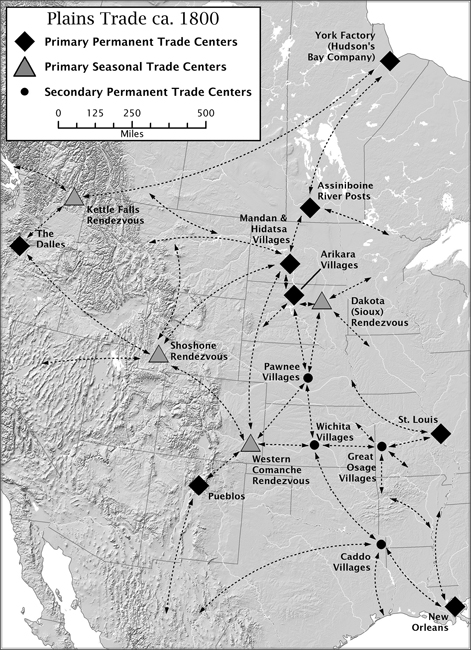

Plains commercial traffic turned on a series of distribution centers. Permanent marketplaces, open for business year-round, included the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, which as we have seen traded with nomads from the northern and central plains and had ties to peoples near Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes. Downriver, Arikaras bought, sold, and bartered with many different Indian tribes, not to mention St. Louis traders. In the Southwest, the Pueblos of New Mexico formed another permanent hub, with a commerce that extended from Mexico to the northern Rockies and the adjoining steppe. Across the continental divide, the Columbia River’s Dalles trading center, in what is now Oregon, serviced peoples from California, British Columbia, and the northwest plains.20 Added to these centuries-old hubs were newer European settlements, many of them dating from the 1700s. For the Mandans, until the 1820s, the most significant of these were quite far from their own territory: St. Louis, on the Mississippi; York Factory, on Hudson Bay; and the assorted fur-company posts on the Assiniboine River.

Seasonal marketplaces helped tie these permanent trade centers together. Most famous was the yearly Shoshone rendezvous, at the headwaters of the Green River in what is now southwest Wyoming. This gathering obviously drew Shoshones. But it also served plateau peoples from the Dalles area, Utes and Comanches from the southern plains and Rockies, plus Kiowas, Arapahoes, and Cheyennes—peoples who traded with the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras—from the central plains region. It attracted traders from the north too, most importantly the Crows, a people whose kinship and commercial ties bound them closely to the Mandans and Hidatsas.21 Years later, American fur traders modeled their own Wyoming trade fairs on the Shoshone rendezvous.

Map 10.1

Two other seasonal trade fairs deserve note. One was the western Comanche rendezvous on the Arkansas River, an eighteenth-century development that modern scholars began learning about only in the 1990s. The other was a similar gathering established by Yanktonai Sioux on South Dakota’s James River in the early 1700s.22

KNIFE RIVER VILLAGES, WINTER 1804–1805

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had flaws as ethnographers. The historian James Ronda has observed that they described some things—especially the “externals of Indian culture”—very well: “village locations, weapons, food, clothing and other material aspects” of Indian life. On the other hand, Ronda notes, they did not see everything, did not describe everything, and did not always understand what they saw. Still, they produced a record of what mattered to them, and one thing that mattered was trade.23 So their observations during the winter of 1804–1805 give us a snapshot of turn-of-the-century trading traffic at the Knife River settlements.

Most of the people engaged in commerce there were Native Americans. On November 5, 1804, for example, an advance party of Assiniboines came to forewarn the Hidatsas that “50 Lodges are Comeing.” Eight days later, Clark reported, “70 Lodges” of Assiniboines with “Some” Crees were “at the Mandan Village.” He guessed there were nine hundred men alone among the Assiniboines and Crees, so the total number of visitors in this single band of trading Indians was probably above three thousand.24

The transactions began on November 14, after all parties had exchanged presents and performed the appropriate “Serimony of adoption.” More than a century after the baron Lahontan had ventured onto the plains with a calumet propped on the prow of his boat, the pipe ceremony continued to ease commerce between strangers. Clark called this “Trafick by addoption.”25

Another advance trading party arrived on December 1. Clark said that six Cheyennes came in “with a pipe” to tell the Mandans that “their nation was at one days march and intended to Come & trade &c.”26 The villagers were suspicious. Cheyenne-Mandan relations had long been troubled, and the visitors’ alliance with the Sioux only heightened distrust. Still, smoking—and presumably trade—ensued.

January 1805 brought still more Assiniboines. Clark noted their arrival at the villages, and the North West Company’s François-Antoine Larocque provided details. There were “about 26 Lodges” with “plenty of skins at their Camp,” he reported. On January 24, he witnessed the classic corn-for-meat exchange: “The Assiniboins all went down to the Mandans to purchase Corn for dried meat, which they brought for that purpose, as there is no Buffalo here.” But the trade went beyond foodstuffs. The Mandans “also barter horses with the Assinniboins for arms, ammunition, axes, kettles, and other articles of European manufacture, which these last obtain from the British establishments on the Assinniboin river.”27

Because Jefferson’s Corps stayed for just one winter, they saw only a fraction of the tribes that came to trade. But William Clark’s inquiries yielded more information. The Mandans, he learned, exchanged articles they acquired “from Assininniboins and the British traders … for horses and leather tents” offered by peoples from the west and southwest, including Crows, Cheyennes, Kiowas, Arapahos, Staitans, and Kiowa Apaches.28

Aside from Native Americans, Lewis and Clark found two other sets of visiting merchants in the Knife River towns: agents of the British fur companies and so-called free traders, without formal ties to the companies. Three Hudson’s Bay Company men—George Budge, George Henderson, and Tom Anderson—arrived twelve days after the Corps did, and seven North West Company men, including Larocque, came two weeks later. Despite obtaining 350 wolf and kit-fox skins in one day at Black Cat’s town, the North West men complained about the increasing competition. At least seventeen company men from the northern posts sold their wares among the villagers that winter. Information and goods circulated together. It took less than three weeks for post supervisors on the Assiniboine River to hear about the strangers flying the United States flag at the Knife River villages. “The Canadians tells me they saw 150 Americans at the Mandals,” wrote the misinformed Brandon House factor John McKay on November 13, 1804. “They arrived in 3 large Boats bound for the Rocky Mountains … Captn. Clerk & Captn Lewis is their Commanders.”29

The free traders included men like Hugh McCracken, who sometimes bought merchandise from the North West Company and sometimes from the Hudson’s Bay Company. He told Lewis and Clark that he and “one other man” had come to the villages with a load of “goods to trade for horses & Roabs.” Some of the traders were Métis—of mixed native and European heritage—and many were “residenters” living permanently or semipermanently with the Mandans or Hidatsas. These men married Indian women, spoke Indian languages, and adopted native ways when it suited them. One such figure was René Jusseaume, one of the “two or 3 frenchmen” Lewis and Clark met at Mitutanka. By this time, having made the villages his home for fifteen years or more, he also “kept a Squaw & had a child by hir,” John Ordway noted.30

At least fifteen other residenters had lived among the Mandans and Hidatsas in the generation before 1804. The most famous of these men is Toussaint Charbonneau, the husband of Sakakawea. The residenter known as Ménard, who lived with the Indians for some twenty-five years, missed meeting the men of the Corps because he had loaded up his furs and left on one of his regular trips north to Brandon House several weeks before they arrived. He reached his destination safe and sound, but his return was ill-fated. Somewhere on the prairies, a party of Assiniboines, angry about incursions on their carrying trade, attacked and killed him.31

BIG HIDATSA, JUNE 25, 1805

When Crow Indians went to trade at the Knife River villages, they “presented the handsomest sight that one could imagine—all on horseback,” wrote Charles McKenzie. For sheer spectacle, nothing compared. Even six-year-old children had their own mounts. Many more horses transported tipis, supplies, bison robes, and trade items. “The whole” exceeded “two thousand,” covering “a large space of ground” and with “the appearance of an army.”32

They knew how to make an entrance too. Nearing Big Hidatsa, the Crows halted on a rise and awaited their chief’s command. When it came, they “descended full speed” and tore through the town below, “exhibiting their dexterity in horsemanship in a thousand shapes.” The North West Company clerk was “astonished” by their skills. “I could believe they were the best riders in the world,” he wrote. The Crows repeated the performance at all the Knife River settlements.33

The villagers reciprocated the next day. Adorned in their “best fineries,” they appeared even “more warlike” than the Crows, who lacked the kind of access to guns, axes, and European goods that the Mandans and Hidatsas enjoyed, though when it came to horsemanship the villagers could not compare.34

The parties spent one more day in ritual preparation for trade—smoking the calumet, performing adoption ceremonies, and exchanging presents. Even the gifts were spectacular. The Crows gave the Hidatsas “two hundred and fifty horses, large parcels of Buffalo Robes, Leather Leggins, Shirts,” and women’s “Smocks … in great abundance.” The Hidatsas gave the Crows “two hundred guns, with one hundred rounds of ammunition for each, a hundred bushels of Indian Corn,” and “mercantile articles, such as Kettles, axes, Cloths &c.” The Mandans, McKenzie said, “exchanged similar civilities with the Same Tribe.”35

When real trading got under way, McKenzie found “incredible the great quantity of merchandize which the Missouri Indians have accumulated by intercourse with Indians that visit them from the vicinity of the Commercial Establishments.” He meant, of course, the goods the villagers got from the Assiniboines, who trafficked between the upper Missouri and the fur-company posts to the north.36

RANKIN STATE PRISON FARM, RANKIN COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI, 1915

The commerce in foodstuffs was symbiotic, the horticultural tribes having an abundance of corn-based carbohydrate, the wandering nations an abundance of bison-based protein and fat. Despite the fishing and hunting that Mandans did on their own, they needed the nomads’ meat, for a maize-centered diet was not without problems.

The worst danger of a corn-based diet was not fully understood until a public-health doctor, Joseph Goldberger, performed an experiment that became a classic in the annals of early twentieth-century science. At the time, Congress was worried, and so were many Americans, because a plague known as pellagra had taken hold in poverty-stricken regions of the United States. Goldberger and other doctors knew its symptoms as the four Ds: dermatitis, dementia, diarrhea, and death. It could appear anywhere, but it seemed to prevail among mill workers, tenant farmers, and southern sharecroppers. South Carolina had reported thirty thousand cases and twelve thousand deaths in 1912.37

Since germ theory had recently gained wide acceptance, many people presumed that an infectious agent caused the disease. But Dr. Goldberger was not one of them. He was a renegade, questioning this accepted but unproven presumption, and arguing instead that nutritional deficiency, not contagion, caused pellagra. So when the U.S. surgeon general asked him to investigate the disease in 1914, he devised a series of experiments targeting what he believed was its nutritional underpinning: a protein-poor diet based mostly on corn. The research proceeded unfettered by ethical constraints in 1915, though it would never get past an institutional review board today.38

First, Goldberger ordered special shipments of food for three pellagra-plagued institutions: two Mississippi orphanages and the Georgia State Sanitarium. A control group of residents with histories of pellagra continued to eat the standard corn-laden fare. All the others, with and without pellagra, enjoyed a diverse regimen of meat, dairy products, and vegetables. The outcome was stunning. After a year, nearly half the controls had pellagra symptoms, but those who received balanced meals either stayed well or got well. Yet skeptics professed disbelief. So Goldberger decided to see if he could induce pellagra in healthy subjects by diet alone.39

In 1915, he approached inmates at Mississippi’s Rankin State Prison Farm with a proposal, cleared in advance by Governor Earl Brewer: If prisoner-volunteers would participate in Goldberger’s experiment, the governor would grant them pardons at its end. Twelve men stepped up to the plate, eating little but biscuits, grits, corn mush, and cane syrup for six months. An inflamed prostate caused one subject to drop out; six of the remaining eleven developed pellagra. This time, for the sake of impartiality, the diagnoses came from unaligned doctors rather than Goldberger himself. Although skeptics remained, the results were convincing.40

A corn-based, protein-deficient diet lacks accessible niacin, a micronutrient essential for the nervous system and for a wide array of bodily functions, including digestion, metabolism, and hormone production. (Corn does contain this vital compound, but not in a form human beings can absorb.) In the absence of usable niacin, pellagra looms large.41 Although the illness was common in the South in the early twentieth century and in Europe after maize became widely consumed there, it was rare among Native Americans such as the Mandans, who pioneered the plant’s cultivation.* Why didn’t the maize-loving upper-Missouri farmers get pellagra? It turns out that in the presence of sufficient protein, the body can manufacture its own niacin from the amino acid tryptophan. Thus part of the answer is that the tryptophan-laden flesh of fish, fowl, and game—especially bison—brought nutritional balance to their menu, and so too did sunflower seeds and beans.42

Another part of the answer lies in the way the villagers prepared corn. Some they ate fresh. Some they parched. Some they boiled. Some they popped. Some they ground into meal for mush or for corn balls. But two cooking methods were especially significant: boiling dried corn in a wood-ash-based lye solution yielded lye-made hominy; and boiling ground corn with salts from nearby alkaline springs yielded a polenta-like mush. In both dishes, the alkaline treatment—by salt or by lye—converted corn’s inaccessible niacin into a form the human body could use.43

FOOD ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS

Still, nomads had the nutritional advantage over settled tribes. Fat and protein, unlike carbohydrate, are essential to human growth and survival, and thanks largely to the bison at their disposal, the itinerant nations of the North American plains were the tallest people in the world in the mid-nineteenth century.44

The hunting tribes did face dietary obstacles, however. One was famine. A migratory lifeway meant carrying everything on the march, a limit on food storage if ever there was one. For this reason, the plains nomads literally stored calories on their own bodies, feasting royally after successful hunting forays. Some European observers viewed this as senseless gluttony, but French fur traders adopted the same practice themselves.45

The nomads also preserved meat for future use. Most famously, they made pemmican, a mixture of pulverized jerky, or dried meat, and marrow fat (sometimes combined with saliva and dried fruit).46 Pemmican was relatively condensed and massively nutritious. But one still had to carry it when on the move.

Another problem for nomads was protein poisoning. Essential at appropriate levels, protein becomes toxic when it makes up too high a proportion of caloric intake.47 Arctic travelers named the condition “rabbit starvation” in reference to the effects of ingesting nothing but the lean meat of northern rabbits. In 1944, the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson gave a firsthand account: “You eat numerous meals,” he wrote, but “you feel hungry at the end of each.” Soon your stomach distends, and diarrhea sets in. “Death will result after several weeks.”48 Consumption of adequate levels of fat or carbohydrate alleviates the ailment, the latter being the more effective cure.49

Rabbit starvation regularly threatened northern plains hunters in late winter and early spring, when bison and other game animals were themselves depleted of body fat. In 1830, the trapper Warren Ferris and his companions endured protein poisoning when they could find only starved, lean bison to eat. “We … found the meat of the poor buffalo the worst diet imaginable,” he wrote, “and in fact grew meagre and gaunt in the midst of plenty and profusion. But in proportion as they became fat, we grew strong and hearty.” Plains nomads faced the same problem. Despite the benefits of their fat- and protein-rich resources, their lives at times depended on reliable, easy-to-carry grain stores.50

There were thus two ways of living on the plains. One was to hunt on the steppe. The other was to farm in the river valleys. The traffic in foodstuffs made each more sustainable.