THIRTEEN

Visitations: Rats, Steamboats, and the Sioux

KNIFE RIVER VILLAGES, 1825

English-speakers call the creature by many names: Norway rat, brown rat, sewer rat, wharf rat. Its Latin name is Rattus norvegicus. The Mandans first met it in 1825, when Henry Atkinson’s massive military force landed at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. At least two—one female and one male—disembarked at the Knife River villages.* Had an army keelboat not brought them, the steamboats that followed surely would have.

Compared with smallpox, measles, cholera, and whooping cough, the brown rat was a newcomer to North America, having arrived in the mid-1700s, probably aboard a ship from England. By 1812, it had reached Kentucky, and thirteen years later, it got to the upper Missouri.1

Figure 13.1. Mus decumanus, Brown, or Norway Rat … Male, female & young.

For Hidatsas, the sight of a new creature was a momentous occasion, perhaps even a visitation of the spirits. When George Catlin came on the scene a few years later, this major event was still being discussed and elaborated. As he heard the story, “hundreds came to watch and look” at the strange animal. “No one,” he reported, “dared to kill it.”2

The deer mouse, a native species, had long plagued upper-Missouri earth lodges, whose inhabitants complained that the little rodents were “very destructive,” gnawing “clothing, and other manufactures to pieces in a lamentable manner.” So when the villagers saw a Norway rat devouring a deer mouse, they were initially delighted. If the newcomers multiplied, perhaps they would rid Indian homes of the bothersome deer mice. Perhaps the spirits had indeed intervened.3

The rats multiplied at a rate hard for human beings to comprehend. Some wild rats live as long as three years, but one year is average. Brief though it may be, that twelve-month life span is sufficient for a female brown rat to accomplish impressive reproductive feats. She reaches sexual maturity at three to four months and then is virtually sure to conceive each time she is fertile, for during a single six-hour fertile period she might mate as many as five hundred times. After she has mated successfully, pregnancy lasts about twenty-three days, and she can breed again less than twenty-four hours after delivering. A normal litter yields six to eight pups, and a typical female has seven litters a year, or roughly fifty offspring.4

As luck would have it, these invaders were particularly successful at the Knife River villages, having stumbled into an unlikely bonanza. Centuries of experience had taught the Mandans that deer mice did little to damage subterranean grain caches; deer mice often occupy the burrows of other animals but do not dig much themselves. The Norway rat, by contrast, burrows assiduously and even creates its own underground food depots.5

Thanks in part to this digging behavior, the rats of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch soon exploded in number, devouring corn by the ton and threatening the villagers’ very livelihood. The invaders rid the earth lodges of deer mice and established their own niche. Too late, the Indians realized that any damage the deer mice inflicted paled next to that caused by the newcomer.

Seven years after the rat’s arrival, George Catlin reported that Mandan “caches, where they bury their corn and other provisions, were robbed and sacked.” The maize in many of these repositories, beneath the floors of native lodges, actually supported the earth that people walked on. But now, Catlin said, “the very pavements under their wigwams were so vaulted and sapped, that they were actually falling to the ground.”6

Fort Clark too was infested. Maximilian complained in 1833 that the post’s “single tame cat” did little “to lessen the tremendous plague of rats.” Lodged in newly constructed living quarters, the prince and his two companions at first went unmolested, but then the rodents “gnawed holes in the floorboards so we could enjoy their visits.” The globe-trotting Europeans had captured and domesticated a young kit fox in the course of their travels, and now the animal earned its keep killing rats for its masters. When the sound of gunshots alarmed the men one night, they learned that post personnel were merely shooting rats in their quarters.7

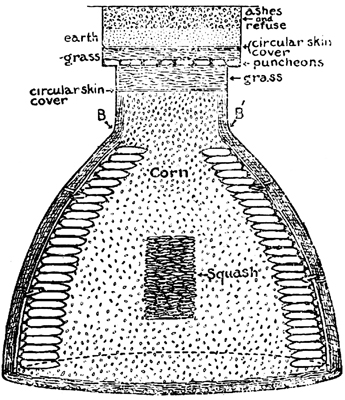

Figure 13.2. A Hidatsa cache pit, redrawn from a sketch by Edward Goodbird. “We built our cache pits so that they were each the size of a bull boat at the bottom,” Buffalo Bird Woman explained. Large cache pits were taller than the women who used them and required the use of ladders. Deer mice occasionally got into cache pits, but they inflicted little damage compared with that caused by the Norway rat after 1825.

In Fort Clark alone, by one report, the rodents “consumed five bushels of corn”—some 250 pounds—each day. Of course the Mandan towns stored much more grain than the post did, but no estimates exist of the damage done in the villages. If Norway rats ate 250 pounds of grain a day at Fort Clark, they undoubtedly ate much more at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch and Ruptare. The Indians were disconsolate. The rats were “a most disastrous nuisance, and a public calamity,” they told Catlin.8 Far from being a blessing, the creatures were a curse. And there were additional setbacks to come.

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, JUNE—“MOON OF THE SERVICEBERRIES”—18329

Could it be the sound of thunder? If Catlin’s account is reliable, that is the question that went racing through the minds of the Mandans at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch on a spring day in June 1832. Rain had not fallen for weeks, and the green corn celebration was in jeopardy. The women of the Goose Society had done what they could. Others with rainmaking rights may have tried too: Big Bird bundle owners, who invoked the winged creature that spread thunder and lightning through the sky, and Snake bundle owners, who invoked river-borne water spirits that might likewise bring rain.10

So this midday rumbling was cause for joy. The rainmaking participants poured out of the town’s ceremonial lodge. Villagers gathered to congratulate Wak-a-dah-ha-hee, the White Buffalo’s Hair, for bringing the spirits into action. But on top of the earth lodge, Wak-a-dah-ha-hee could see farther than the others. He scanned a cloudless sky for signs of rain and saw nothing. Instead, just below the horizon, he spotted something never before seen on the upper Missouri. The distant noise came from a steamboat, belching smoke as it churned upstream. The previous summer, the side-wheeler Yellow Stone had gotten to central South Dakota on its inaugural Missouri River voyage. Now, returning upriver from St. Louis, it was entering Mandan country for the first time, firing signal cannons to announce its approach.11

According to Catlin, the warriors prepared Mih-tutta-hang-kusch for a “desperate defence.” When the steamer drew alongshore, there was “not a Mandan to be seen” on the riverbanks. The villagers set aside their fears of the oversized alien fortress only when they saw a familiar man, John Sanford, disembark. Sanford was the U.S. subagent to the Mandans, and he was returning from a trip to Washington, D.C.12 (The Indians apparently liked him, but his later legacy to American history was grim. In 1857, Sanford became known as the successful defendant in a high-profile freedom suit brought against him by a Missouri slave named Dred Scott.*)

Figure 13.3. Snags (Sunken Trees) on the Missouri, aquatint print of the steamboat Yellow Stone (after Karl Bodmer). George Catlin, who took the Yellow Stone to Mih-tutta-hang-kusch in 1832, was followed by Karl Bodmer and Alexander Maximilian, who traveled on the same vessel to Fort Pierre in 1833. There they boarded another American Fur Company steamer, the Assiniboin, to reach the Mandans and eventually Fort Union.

George Catlin had a propensity to exaggerate. He took liberties in both his literary and figurative portrayals. And since he was himself on the Yellow Stone, he could not have seen Wak-a-dah-ha-hee’s rainmaking or the villagers’ initial reaction to the steamer in the distance. But circumstances seem to corroborate his version of what happened. Prince Maximilian noted that 1832 had indeed been a dry year, and the first appearance of a steamboat drew powerful responses everywhere. In 1807, when Robert Fulton’s North River Steam Boat had chugged up the Hudson River for the first time, an eyewitness reported that “some imagined it to be a sea-monster, whilst others did not hesitate to express their belief that it was a sign of the approaching judgment.”13

Catlin reported something else that might warrant astonishment. As evening approached on that very day, a rainstorm erupted. It poured “down its torrents until midnight.” The cloudburst delighted the Mandans, and “a night of vast tumult and excitement ensued.”14 The midday rumblings of the Yellow Stone had yielded to more familiar and beneficial thunder. But the steamboat’s arrival portended turbulence to come.

ST. LOUIS TO FORT UNION, 1833

Another year, another painter. Steamboats carried tourists and paying passengers to the upper Missouri from the start. When the Yellow Stone left St. Louis on April 10, l833, for its third trip upstream, the list of fares included a Swiss painter named Karl Bodmer, who was traveling with the German prince Maximilian of Wied and a hunter-taxidermist named David Dreidoppel. Bodmer and Dreidoppel were there at the prince’s behest, assisting him in documenting North America’s peoples, landscapes, and creatures. Dreidoppel hunted and preserved animal specimens while Bodmer painted and Maximilian wrote.

The Yellow Stone did not take the three foreigners all the way to the Knife River. Instead, on May 30, it dropped off its passengers and turned around at Fort Pierre, the American Fur Company post in present-day South Dakota.15

The sights and sounds of Fort Pierre enchanted the visitors. They had never seen the North American prairies, and they had glimpsed only the remnants of eastern tribes during their earlier travels. The western peoples whose lives had changed so much less than those of their easterly cousins were a novelty. “The vast, now beautifully green prairie afforded an interesting view,” Maximilian wrote. “Horses and cattle” grazed nearby, and Sioux tipis, with their “conical points,” offered “a singular sight.” The newcomers spent the next five days mingling with post personnel and the Yankton and Teton Sioux. They visited the Indians’ tipis, admiring their quillwork, their pipe bowls, their face paint, and their horsemanship.16 Bodmer created several portraits of Lakota women and men.

On June 5, the threesome boarded another steamboat, the American Fur Company’s brand-new Assiniboin, and headed upstream toward the Mandans. They passed Eagle Nose Butte, the mouth of the Heart River, and came to “a green plateau where a Mandan village once stood.” That was Double Ditch, now empty.17

Two weeks after leaving Fort Pierre, the vessel moored at the adjoining settlements of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch and Fort Clark, drawing spectators from far and wide. “The whole prairie [was] covered with men on horseback and on foot,” Maximilian said. The leading Mandan men boarded the Assiniboin even before the passengers could debark. In a crowded ship’s cabin, the German prince watched as they seated themselves in council to discuss (and reject) a proposed accord with the Sioux. The Indians were “powerful, tall, robust men,” he wrote, marveling at their long hair, clubs, tomahawks, and eagle-feather fans bound in red cloth.18

The Mandans and their community captivated Maximilian. Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, he noted in his chronicle, contained sixty-five lodges surrounded by an irregular palisade, and it brimmed with activity. “Indians of all ages and both sexes on horseback and on foot moved back and forth,” he observed—“brown, often reddish brown, black-haired figures in colorful dress and faces painted red.” A Crow band had come in to trade, and “a large number of horses grazed everywhere.”19

The Assiniboin and its European contingent stayed at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch overnight and then steamed upstream. They passed the little Ruptare town with its thirty-eight lodges. Here too, the scene teemed with people—some riding horseback, some lining the riverbank, and many perched atop their houses to get a better view of the boat and its passengers.20

Maximilian and his companions eventually left the vessel at Fort Union. From there, they explored the upper reaches of the Missouri over the summer and into the fall, returning in November to Mih-tutta-hang-kusch and Fort Clark for the winter. Here Maximilian’s fascination with the Mandans continued.

MISSOURI RIVER, SUMMER 1833

After delivering Maximilian, Dreidoppel, and Bodmer to Fort Pierre in May, the Yellow Stone had returned to St. Louis and spent the summer plying the waters below Council Bluffs. But these seemingly mundane activities belie the vessel’s larger significance. A year earlier, the Yellow Stone had been the first steamboat to ascend the Missouri River all the way to Fort Union. The craft thus epitomized the growing reach of the St. Louis fur trade and especially the growing reach of the American Fur Company, controlled until the next year by a butcher-turned-financier named John Jacob Astor.

The Yellow Stone was a company ship. Its purpose was to ferry people, goods, and pelts to and from posts such as Fort Pierre, Fort Clark, and Fort Union. No longer would fur traders depend solely on human-powered canoes, bull boats, keelboats, pirogues, or mackinaws; on its inaugural voyage to Fort Union in 1832, the Yellow Stone had carried nearly a hundred people and a year’s worth of supplies to posts as far up the Missouri as the Yellowstone River confluence.21

For all their practicality, steamboats had drawbacks. One was their appetite for wood. The Yellow Stone probably consumed ten or more cords per day, enough to fill a railroad flatcar. Larger boats could burn seventy-five cords per day—enough, according to one historian, to build fifteen “small framed houses” of thirty-two square feet. Mandan earth lodges might make for a similar comparison. The historian Donald Jackson has estimated that on the round-trip that carried Bodmer and Maximilian to Fort Pierre, the vessel burned “the equivalent of 1700 oak trees that might have been growing for half a century.”22

Steamboats typically paused morning and afternoon to land woodcutters whose work kept the ship’s fireboxes stoked.23 Paying passengers could travel at reduced rates if they agreed to lend a hand. The task was not difficult along the lower sections of the Missouri, where ample forests recurred along the riverbanks. But trees became less abundant higher up, in the semiarid country of the Dakotas. Here the Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas depended on river-bottom cottonwoods for firewood, horse fodder, and earth-lodge construction.

Only in the early twenty-first century have historians begun to examine the extent to which Native Americans and steamboat “woodhawks” competed for timber. The population collapse in 1781 had eased the Indians’ pressure on upper-Missouri trees, but growing herds of horses had had the opposite effect, since the Indians fed their mounts cottonwood bark and branches in winter. Then steamboat traffic tipped the ecological scales further away from the Mandans and Hidatsas and contributed to their nineteenth-century impoverishment.24

Fuel supply was only one challenge faced by the steamers and their crews. The Missouri River posed its own obstacles, including snags and sandbars that waylaid even the finest pilots. Moreover, the technology was new and engines were fickle. Muddy water clogged boilers and flues; sparks ignited shipboard fires; and boilers exploded, destroying vessels and human lives.

For the Mandans and their neighbors along the river, the growing boat traffic carried hidden hazards, as the appearance of rats made clear. Aboard steamboats, the problem was not the goods listed on official bills of lading, although some, like alcohol, had their own inherent risks.25 Far more hazardous were the invisible cargoes the vessels could carry, unwanted stowaways with lethal power.

In June 1833, right after dropping off Maximilian at Fort Pierre and returning to St. Louis, the Yellow Stone steamed upriver again. On board was the cholera bacterium. Cholera’s symptoms are fearsome, the most infamous being an acute diarrhea that can dehydrate and kill a victim in hours. Contaminated food and water spread the infection.26

The disease had arrived in Canada in June 1832 with the annual wave of European immigrants; once in the United States, it traveled west from one city to another, and by May 1833, St. Louis residents were succumbing.27 When the pestilence erupted aboard the Yellow Stone in June, the vessel must have still been close to its home port, but it continued upriver. By the time it reached the Kansas River confluence—at present-day Kansas City—it could proceed no farther. Eighteen-year-old Joseph La Barge was one of the few crew members left alive. He later told Hiram Chittenden the story.

With “his pilot and most of his sub-officers” dead, Captain Andrew Bennett left the ship and returned to St. Louis to hire a replacement crew. He put the vessel in La Barge’s hands for the interim, and the budding riverboat pilot managed the steamer by himself. He fired the boilers long enough to get beyond the range of frightened Missouri residents who threatened to burn the cholera-infested vessel. La Barge was on his own. Even the Assiniboin, a kindred craft in the American Fur Company fleet, refused to heed his distress signal. So La Barge and the Yellow Stone waited. “There is a spot just below Kansas City,” he said, “where I buried eight cholera victims in one grave.”28

Eventually, Captain Bennett returned with a company of substitute deckhands. They must have been brave or desperate men to sign on to a vessel known to have cholera on board. On August 2, the steamer moored at Fort Leavenworth. The pestilence wreaked havoc on the lower Missouri River, and residents blamed the Yellow Stone for transmitting the infection. “By the steam boat Yellow Stone, the cholera was brought into our neighborhood,” claimed a Missouri minister looking back over the disruptions of “the past summer.”29

In November, Maximilian and his two companions settled in for the winter at Fort Clark, beside Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. The prince suggests that dangerous microbes were circulating broadly among the Mandans at this time. “Spring [and] fall, as well as winter, bring several minor indispositions,” he wrote, “indispositions” more fatal to Indians than to others. During his five months among the villagers, “Whooping cough took many children,” and “diarrhea and stomach disorders also took several.” With cholera on a rampage along the lower Missouri, Maximilian reported that “some believed” it reached the Mandans as well.30

The prince’s discussion of cholera is all too brief and equivocal. In July 1851, when the Swiss artist Rudolph Friederich Kurz visited the upper Missouri, he heard that the villagers had suffered a “disastrous” epidemic of cholera in 1834, right after Maximilian and Bodmer left. But this claim seems dubious. The 1830s cholera, if it reached the Mandans, would probably have done so a year earlier; moreover, the fur trader Francis Chardon did not mention an 1834 or 1835 epidemic in his journal. In fact, Kurz had reason to be defensive: His own conveyance, the steamboat St. Ange, had carried cholera upstream in 1851.31 One thing is clear: Infectious disease was insidious and relentless.

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, EARLY 1830S

Among the chiefs who boarded the Assiniboin to greet Maximilian and his party on June 18, 1833, were Charata-Numakschi (Wolf Chief) and Mato-Topé (Four Bears)—the first and second chiefs of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch.

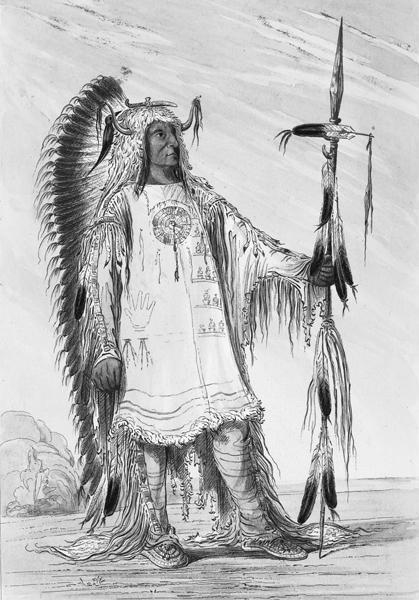

Figure 13.4. Ha-na-tah-numauk (the Wolf Chief), portrait by George Catlin. Maximilian, who spent much more time at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, rendered the chief’s name as Charata-Numakschi but provided the same translation. Despite having a higher rank than Four Bears, the Wolf Chief was less popular, and he did not impress non-Indian guests the way Four Bears did.

Charata-Numakschi, according to George Catlin, was a “haughty, austere, and overbearing man, respected and feared by his people rather than loved.” But Mato-Topé was the “most popular man in the nation.” He made an impression on almost everyone. He won the admiration of his people, of white visitors, and even of his enemies. Not long after he died, the French mapmaker Joseph Nicolas Nicollet met a Sioux chief who took his name—Matotopapa—after the Mandan leader.32

Mato-Topé’s father, Good Boy, was the esteemed On-a-Slant chief who had taken charge of the west-side Mandans after the epidemic of 1781. The apple fell close to the tree. On the basis of his courage, character, and generosity, Four Bears ascended to the position of second chief at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch when he was in his twenties and not even yet a bundle owner. This probably meant that he gave the Okipa ceremony while he was still a young man. He sponsored it again in the summer of 1834, after Maximilian left. Since giving the Okipa meant parting with an enormous amount of personal wealth, this meant Four Bears was a very poor—and very great—man.33

With James Kipp interpreting, Four Bears spent hours in conversation with Catlin and Maximilian, relating personal and tribal history. Several other Mandan leaders also contributed to these authors’ investigations. Foremost among them was Broken Arm, who told Maximilian story after story from the surviving archive of Mandan traditions.

Catlin and Bodmer both created portraits of Four Bears. Unlike some other Mandan leaders, the chief was not an especially big man, but his presence was imposing. Both painters portrayed him splendidly attired in clothing that conveyed status and valor. His horned headdress of eagle feathers swept to the floor. Although he wore different tunics in the two portraits, the left sleeve of each bore hash marks that represented the many times he had counted coup on his enemies. Figures of scalped foes ran down the left side of the outfit he wore for Catlin, who later bought and then lost the chief’s shirt.34

Figure 13.5. Mah-To-Toh-Pah. The Mandan Chief, by George Catlin. Four Bears, the second chief of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, was greatly admired by all. The cross-mounted feather on his spear recalls the night he took revenge on his brother’s killer. From Catlin’s North American Portfolio.

Figure 13.6. Mato-Tope: Mandan Chief, aquatint print (after Karl Bodmer). The symbolic cross-mounted feather appears again.

In both images, Mato-Topé’s spear bears a single feather mounted crosswise near the tip. This recalls the chief’s greatest exploit, which took place after his brother died by an Arikara spear. Mato-Topé told Catlin that when he found his brother dead, he extracted the weapon that had killed him and kept it for four years, until he could no longer contain his desire for revenge. He then trekked alone to Arikara country and, in the dark of night, sneaked into the killer’s village, slipped into the earth lodge where the man slept, seated himself by the fading fire, and ate a full meal from the cook pot that hung over it. Then he sent the man to his death with the spear that had killed his brother. The quill in question fell off the lance as he plunged it into his victim, and he saved it as an emblem of divine intervention.35

FORT CLARK, 1834

Francis Chardon, according to a fellow fur trader, was “a very singular kind of man”—crusty, sarcastic, and bitter.36 The American Fur Company posted him to Fort Clark in 1834. But he did not like the Mandans and was deeply unhappy at the post.

Chardon kept a journal during his first five years beside Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. Unlike his contemporaries Catlin and Maximilian, he had little interest in Mandan belief systems, material culture, history, or customs. When these topics appear in his writings, they do so in passing and rarely in detail. But Chardon did describe the events of daily life that mattered to him. These were not necessarily the events that mattered to the villagers, nor did villager and fur trader interpret them the same way. But precisely because of its emphasis on the mundane, Chardon’s diary yields valuable glimpses of upper-Missouri life in the mid-1800s.

Rats were one thing that Chardon chronicled assiduously. He kept a running tally of the rats he killed at Fort Clark each month, tracking the dead animals with as much care as he tracked the beaver and bison robes he took in:

June 1836: “Killed 82 Rats this month.”

July 1836: “Number of Rats Killed this month 201.”

August 1836: “Killed 168 Rats this Month—total 451.”

September 1836: “Killed 226 Rats this Month = 677.”

October 1836: “Killed 294 Rats this Month = 971.”

November 1836: “Killed 168 Rats this Month—Total 1139.”

December 1836: “Killed this Month 134 Rats—total 1,273.”

January 1837: “Killed this Month 61 Rats—total 1334.”

February 1837: “Killed 89 Rats this Month—total 1423.”

March 1837: “Number of Rats Killed this Month 87—Total 1510.”

April 1837: “Killed 68 Rats this Month—total—1578.”

May 1837: “Killed 108 Rats this Month—total 1686.”37

Two years later, Chardon had his men replace the pickets surrounding Fort Clark because the old ones were eaten “off at the foundation by the Rats, and in a fair way to tumble down.” Twenty-first-century archaeologists call “the dominance of the Norway rat” the “most striking feature” of the trading post’s animal remains.38

MANDAN-HIDATSA VILLAGES IN THE EARLY 1830S

The new keelboat and steamboat traffic from St. Louis—supplemented by occasional overland visitors from the Columbia Fur Company’s Lake Traverse depot on the South Dakota–Minnesota border—had brought the villagers firmly into the embrace of the United States.39 Well-stocked Fort Clark sat beside the Mandans, and other U.S. traders circulated among the Hidatsas. So the villagers no longer needed the British manufactured goods that Assiniboines had once ferried south across the plains.* But they still needed bison products, especially meat and fat, a requirement that became more pressing as corn supplies dwindled and trade with nomads slumped.

Hidatsas had always taken to the chase frequently, so they may have suffered less than Mandans when rats ate their corn. “The Mandans are a much more stationary people than almost any other tribe in this whole region of country,” reported a visitor to Council Bluffs in 1835. Alexander Henry likewise found the Mandans (and Awaxawi Hidatsas, who lived in the village closest to them) more “stationary” and more “given to agriculture than their neighbours.”40

But rats obliterated the horticultural bounty that had underpinned centuries of Mandan wealth and stability. Even when the women brought in bumper crops, provisions vaporized from their caches. Then, a distillery installed at Fort Union—possibly as early as 1828—increased the demand for corn. According to one trader, the grain that went to the still came “from the Gros Ventres [Hidatsas] and Mandans.”41

The villagers continued their corn trade with company men and Indian visitors, but not without opposition. When a poor crop threatened Mandan livelihoods in 1834, some villagers spoke up for keeping more of the harvest for the community’s own use. According to Francis Chardon, “they harrangued in the Village to trade but little Corn, as starveing times are near at hand.” But the Mandans nevertheless sold twelve bushels to the Fort Clark supervisor that very day.42 Such transactions may seem imprudent, but they probably were not: It was better to extract some value from the grain than give it up to the rats.

Strapped for corn, the Mandans might logically have turned to bison for sustenance, but this was no longer easy. The encroachments of Lakotas and other enemies had made it dangerous to venture abroad. At risk were not just the hunters but also their families and friends who stayed at home without protection. As early as 1801, an observer had noted that the Mandans could not hunt “on account of their wars.” A generation later, they seemed to be at war with everyone except the Hidatsas and Crows. “They are at peace with the Häderuka (Crows),” Maximilian wrote, but he reported that their foes included Blackfeet, Sioux, Arikaras, Assiniboines, and Cheyennes.43

Of these rivals, none represented a greater challenge than the bands of Sioux that continued to press westward from their Minnesota homelands. Mandan relations with the Lakotas cycled hot and cold, trading one day, fighting and thieving the next. But the balance of power shifted steadily toward the Sioux. Their full-fledged adoption of horse culture had made them a dominant force, and they reveled in their military skill. One Lakota winter count bragged of killing “many Mandans” in 1828. Another put the death toll at two hundred Hidatsas. Sioux warriors were even known to use bison decoys to lure Mandan hunters to their deaths.44

By the late 1820s and early 1830s, the Mandans lived under something just less than a siege, and when they did pursue game, they took measures to curtail the danger. They “sildom go far to hunt except in large parties,” William Clark had observed in 1805. Maximilian confirmed this: “The men usually move out in numbers” to hunt “because they are safer from their enemies than if they go individually.” Seeking safety in the aggregate, Mandan hunters often recruited Hidatsas to join them.45

Events in the spring of 1834 attest to the ferocity of Lakota warfare. Sometime during late April or early May, Sioux warriors burned the two “lower” Hidatsa settlements to the ground; they were never occupied again. Hidatsa refugees took shelter at Ruptare and Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. Some may have stayed with the Mandans for good, while the rest probably moved to Big Hidatsa, which survived the attack. In a single blow, the Lakotas had reduced the Hidatsas from three towns to one. Now only three permanent villages survived in the Knife River region: Big Hidatsa in the north, Ruptare (the “Little” Mandan village) in the middle, and Mih-tutta-hang-kusch in the south—all within a nine-mile span of river and prairie.46

MANDAN VILLAGES, JULY 1834–JULY 1835

The destruction of the two Hidatsa towns was a chilling catastrophe. And it also showed how combustible intertribal relations could be. Francis Chardon’s diary from that time suggests that the Mandans now lived in a state of perpetual anxiety about Sioux warriors nearby.47

On July 23, a battle between the villagers and the Yanktonai Sioux left five Mandans wounded and one Mandan, one Hidatsa, and one Sioux dead. False alarms thereafter kept Mih-tutta-hang-kusch residents jittery for weeks. On August 17, a successful Mandan bison hunt should have been cause for celebration, but Sioux warriors frightened the hunters as they came home, causing them to drop their meat and flee. At night, the Mandans kept watch “for fear of Enemies.”48

Another scare came six days later, when a handful of Yanktonais on the far side of the Missouri exchanged a few shots with residents of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. It was berry-picking time, the “moon of the ripe plums.” Buffalo berries and choke cherries were in season. But the Mandans “did not think it prudent to cross the river” to harvest them. An elderly couple had already done so, and with the enemy on the prowl, the villagers feared for their safety. That night they learned that both “were Killed, scalped, and butchered.”49

On September 6, the villagers woke to the first frost of the season. A Mandan man went out to gather wild plums. He did not return. The next day, a search party “found him dead—and scalped” a mile from Mih-tutta-hang-kusch.50

Strange though it may seem, a Yankton Sioux band arrived to trade on September 15. The visitors sold bison robes and beaver pelts to Chardon at Fort Clark, but they got the cold shoulder at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. At the Hidatsa towns, they patched things up enough to smoke and feast together before leaving on September 18. It took only two days for the Yanktons to return on a different mission: a battle that took the lives of two Hidatsas and one Mandan.51

In November, two Mandans set out for a Yanktonai Sioux camp on the Cannonball River, more than sixty miles south; they intended, according to Chardon, to serve “as deputys for the Village.” Four days later, another party headed for the same destination “on a war excursion.” Neither group appears to have entered the Sioux camp. Its size—350 tents—may have put them off.52

On November 30, “several Yanctons” traded peacefully at Fort Clark. Two or three hundred more likewise traded a month later. But on December 31, a Hidatsa slipped into Mih-tutta-hang-kusch and killed a Sioux visitor. The guests left quickly. By January 5, 1835, those Mandans who had taken refuge in their sheltered winter camp for the cold season began to return to Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. “They fear the Scioux,” Chardon explained, “on account of the fellow that was Killed in their Village.”53

The next two and a half months of wintry weather passed quietly, although the Mandans apparently stole a horse from the Sioux near the Heart River. Then, on March 18, a band of Yanktons arrived at Fort Clark, traded 140 bison robes, and left after two days. A Mandan war party quickly followed them, but the men came back within a week “without Makeing a Coup.”54 In late April, a Mandan named Old Sioux went missing. He was “thought to have been Killed by Sioux,” Chardon said. The women of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch got busy restoring the town’s palisade, which had fallen into disrepair.* They feared an imminent “attack from the Sioux.”55

They worried for good reason. In early May, Yanktons attacked a war party of Hidatsas and killed eleven of them. The Mandans got the news on May 7 and spent the night on edge, anticipating an assault that never came. Another “allert” ran through Mih-tutta-hang-kusch on May 12. Again no attack materialized. Three days later, the Hidatsas sent their own warriors out “in search of the Yanctons.”56

In June it was the Mandans’ turn. A small war party—“all on Horse Back”—crossed to the east bank of the Missouri on June 6 looking for Sioux. Another war party left three days later. But both came home without engaging the enemy.57 July produced more of the same. Three Yanktons came to Fort Clark to trade and “to smoke with the Mandans” on July 6. But when “several of the Mandans and Gros Ventres [Hidatsas] talked of Killing them,” they beat a hasty return to their Cannonball River camp. On July 9, a Hidatsa war party returned “with 2 Assiniboine scalps.” Later in the month, several Yanktons traded peacefully, and several Hidatsas even accompanied them back to their encampment on the Heart River. They returned six days later and said “they were well received” by the Sioux.58

The hiatus was brief. Year in and year out, the Sioux drew the noose tighter.