FOUR

Connections: Sustained European Contact Begins

THE NORTHERN PLAINS AND HUDSON BAY HINTERLAND AT THE TURN OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The upper-Missouri villagers, and the Mandans in particular, were not known for hunting far afield or for carrying their wares to distant places. They typically relied on wandering peoples—hunter-gatherers who subsisted on bison meat, prairie turnips, and other foods collected in seasonal treks over the prairie—to handle these tasks. These peoples visited the earth-lodge settlements of the farmer-hunters with growing frequency after 1400 or so, establishing a pattern that persisted for centuries and eventually made those communities a destination for Indians and Europeans alike.

The visitors from the south and west included Arapahos, Crows, Shoshones, Kiowas, and probably their forebears. From the north and east came Crees, Assiniboines, Ojibwas, occasional Lakotas, and perhaps even Blackfeet and their predecessors. The nomads carried Dentalium shells, copper items, pipestone, and exotic tool-making materials to their hunter-farmer trading partners on the Missouri.1 If the commerce witnessed by eighteenth-century Europeans is any indication, they bartered in bison products too. And eventually, when Spanish, French, and English colonizers established a presence on the fringes of the plains, itinerant peoples also carried items from these newcomers to the villagers.

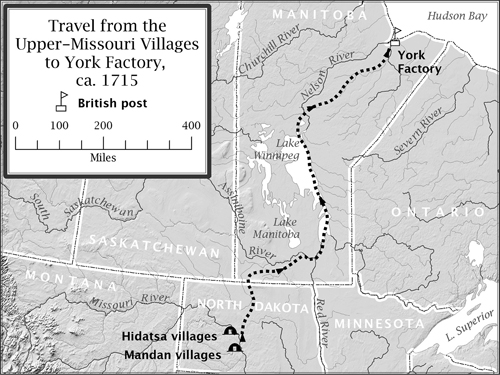

In the early 1700s, only a few Mandans or Hidatsas appear to have visited European outposts themselves. If brief historical references are any indication, the first to do so were not volunteers but vassals—townspeople taken in warfare by Crees or Assiniboines before they negotiated peace with the upper Missourians in 1733. Between 1709 and 1714, Crees and Assiniboines visiting Europeans at Hudson Bay brought such captives with them “expressly to show” that their stories of the Missouri River peoples were true. The enslaved strangers said they grew a grain that listeners believed “must be maize.” The visitors also related stories about bearded Spaniards, whom they had heard about from other nations who visited their settlements.2

Depending on the route taken, the distance from the Mandan and Hidatsa villages to Hudson Bay was roughly nine hundred miles. But two upper-Missouri children made an even longer journey. Like others, the children were captives, purchased from Crees or Assiniboines by a French trader named Christophe de la Jemeraye. In 1733, La Jemeraye traveled eastward with his youthful charges and sold them or dropped them off in Montreal. Later, when he got to Quebec, he described them to the French governor: “In their games they neigh like horses,” he said. And “when they saw cats and horses they said they had animals of the same kind at home.”3

Several upper-Missouri trading parties likewise may have journeyed to the new European outposts. The evidence is not easy to interpret. It hinges on the travelers’ covering great distances and adopting canoes in place of the round, bison-hide bull boats they used at home.

On June 12, 1715, a quirky, hardheaded administrator named James Knight reported the arrival of “Eleven Cannoes” of so-called “Mountain Indians” at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s York Factory outpost. They traded two days later. With an eye toward bringing more “of these most Remotest Indians” into the trade, Knight gave his guests tobacco and other gifts to carry home.4

Ensuing events suggest that the term “Mountain” may have been Knight’s transcription of the Assiniboine Mayatáni or Mayatána, terms for “Mandan.”5 A year later, Mountain Indian traders came to York Factory again. They arrived on June 15, some thirty-six canoes in all. Knight’s efforts to enlarge his commerce had worked. But the York Factory master had a problem. The annual supply ship had not shown up at the end of the previous season, so he had no goods to offer, and the Indians had only two options: They could go home empty-handed, while favorable summer conditions persisted, or they could wait for months until the next ship came in, chancing a hazardous return trip in the darkness of the subarctic winter. Most of the Mountain Indians turned back, but some decided to wait, and Knight took advantage of their presence to find out more about their lifeway and country.6

Map 4.1

The Mountain Indians told him they lived far to the south, beyond the Assiniboines, in a land with a climate suited for a settled, horticultural life. They were farmers, not nomads. There were “Sev’ll Nations of them,” Knight learned, and their villages contained an “abundance of Natives.” Their fields flourished with “Indian corn” as well as “Plumbs” and “Hazle Nutts.”7 The Mountain Indians had come from farther away than any of the other groups that had made it to York Factory. Their journey to the post had taken them thirty-nine days. Their return, fighting against river currents much of the way, took a wearying four months.*

The Hudson’s Bay Company’s commerce with the Mountain Indians dropped off after the disappointing events of 1716. A party traded with James Knight the next year. Another may have visited York Factory in 1721. But thereafter they disappear from the records kept at the post. The 2,000-mile round-trip effort was not worth it. The Indians, Knight wrote, would not come “1000 or 1200 Mile[s] to give away there goods for to have little for it.”8 Why make the trip to the British trading factory now that French options lay closer at hand?

If the Mountain Indians were indeed Mandans or Hidatsas, there was another obstacle that may have impeded their trade with York Factory. According to the governor of New France, the Crees and Assiniboines, who occupied the territory between the upper Missouri and Hudson Bay, “constantly made war” on the Mandans in these years. Not until 1733 did the nomads make “peace with that tribe.”9

Because both sets of peoples had the calumet, the animosity between them may have posed only a minor obstacle. But there can be no question that the accord of 1733 invigorated plains commerce. For the Mandans, the pact assured a better supply of meat, fat, and European-made items, all carried to them by Cree and Assiniboine traders from the north. For the Crees and Assiniboines, it meant a reliable source of Indian corn, described by one historian as their “ideal, portable food supply.”10

THE CANADIAN INTERIOR, 1711–38

Because of competition, glutted markets, and European wars, the Indian commerce that the French had so vigorously pursued in the early seventeenth century languished in the late 1600s and early 1700s. But in 1711, Britain and France agreed to the preliminary terms of the Treaty of Utrecht, and the French—inspired in part by Lahontan’s journey and influential map—enlivened both their trade and their hunt for the Western Sea. Midwestern posts proliferated. By 1718, three trading houses sat near the shores of Lake Superior. Forts and missions appeared in the Illinois country. Then, in the 1730s, explorers pushed northwest from Lake Superior into the parklands that bordered the Canadian plains. They hoped not just to find the elusive sea but also to intercept the cold-country furs that Crees, Assiniboines, and Ojibwas had been carrying to the British at Hudson Bay.11

Deep in the Canadian interior, the French now heard stories galore about the upper-Missouri towns. Cree chiefs told them of distant peoples “lower down” who led “sedentary” lives, raised “crops, and for lack of wood” made “mud huts” to live in. A captive—probably Mandan or Hidatsa—told French traders that the villagers raised “quantities of grain,” gathered fruit in abundance, and hunted plentiful game with bows and arrows. Their towns, he said, were numerous and large, “many of them being nearly two leagues in extent.” Yet another report described houses with “cellars in which they store their Indian corn in great wicker baskets.”12 To French ears, these semiurban, corn-growing people sounded practically European.

In January 1736, a Mandan or Hidatsa envoy traveled with Assiniboine go-betweens to see the French traders at Fort Maurepas, at the foot of Lake Winnipeg. He tried to make it clear that he was not an Assiniboine. “He asked leave to sleep in the fort,” noted an after-the-fact report, “saying he was not a savage like the rest.” But when evening came, the sentry at the front gates “put him out like the others without saying a word about it till several days after he was gone.”13 French officers bemoaned the lost opportunity. It was not long, however, before a man named Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Vérendrye, paid a visit of his own to the upper-Missouri people he called the Mantannes.14

VILLAGES ON THE UPPER MISSOURI, WINTER 1716–17

Whether or not new contagions had contributed to the earlier population collapses at Mandan towns like Double Ditch and Larson, the encroaching presence of non-Indians sent the crowd diseases of the Old World coursing regularly across the grasslands in the early eighteenth century.

One episode occurred in the winter of 1716–17. The plague’s name and character do not appear in surviving records, but the Hudson’s Bay Company trader James Knight described the awful consequences in the York Factory journal on June 11, 1717. The so-called Mountain Indians—quite possibly Mandans or Hidatsas—had returned without the “captain” who led them the previous year. Instead, his son was in charge. He told Knight that “his father” and “all his ffamily” had “been very Sick” and that many had died. “There Losses,” Knight wrote, “is not Recoverable.” Another Mountain Indian confirmed that his people “most all Die’d Last Winter” and that there was “nothing but Howling & Crying Amongst them.” In fact, Knight said, the Mountain Indians were not alone in their affliction: “All in Generall Complain of a Mortallity as hath been among them this Winter.”15

The illness may have been the same one that struck the Yanktonai Dakotas in 1714, described in one winter count as oyáte nawícakséca tánka—“tribe cramps great.” The villagers might have picked up the infection the next year, when the Yanktonai and Mandans counciled together. Or perhaps it was related to a separate episode of cramps that afflicted the Yanktonais and other Sioux bands from 1722 to 1724.16

Although winter counts are incomplete, these Indian-produced documents nevertheless give us a glimpse of the disease environment on the plains for the next two centuries. Between 1714 and 1919, epidemics swept the northern plains on average every 5.7 years. After the cramping episodes of the 1710s and 1720s, smallpox afflicted the Sioux in 1734–35 and killed many Cree Indians in 1737–38. On the Missouri River below the Mandans, the Arikaras too may have taken sick, for they told the St. Louis fur trader Jean Baptiste Truteau in 1795 that they had already had smallpox “three different times.”17

It is not clear which, if any, of these plagues hit the Mandans. But something surely did. In the mid-1700s, the occupants of Double Ditch appear to have altered their village boundaries one more time, taking shelter behind the visible, innermost fortification ditch that marks the site. And when they moved, they did something unusual: They scraped off the entire surface layer of dirt in their village—every surface within the circumference of the two ditches visible today—and dumped it in large mounds outside their shrinking town.18

The late Stanley Ahler, an archaeologist who worked on the Double Ditch project and had decades of experience in the region, observed that such thorough removal of surface dirt was a “very unusual, labor-intensive activity, not well documented at any other Plains Village site.” No one knows what it means. But it is hard to avoid speculating that the Mandans were cleansing their village after a horrific encounter with infection.19

At nearby Larson, a similar contraction took place, though archaeologists have found no evidence of the kind of earth-moving that went on at Double Ditch. Regardless of the cause, one thing is clear: Mandan towns on the east bank of the upper Missouri in the mid-1700s were but shadows of their former selves. With fewer than four hundred people, Double Ditch in its final configuration was 80 percent smaller than it had been two centuries earlier.20 Ironically, it was then, with their numbers plummeting, that the upper Missourians began receiving European visitors regularly, in a pattern established by Pierre de la Vérendrye.

ON THE NORTH DAKOTA PLAINS, NOVEMBER—“MOON OF THE FREEZING RIVERS”—173821

The sight was spectacular to behold: Three long lines of people snaked across the prairie, all on foot, marching Indian-fashion—single file—over a sea of grass.* Their direction was southwestward. Pierre de la Vérendrye was on his way.

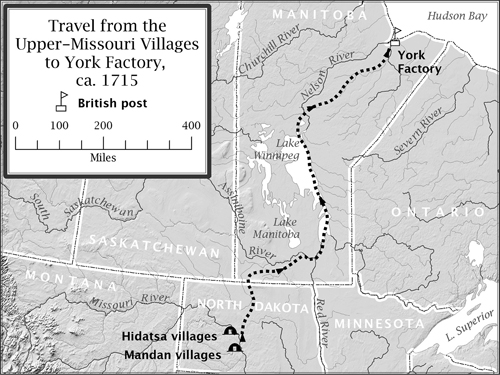

For more than two decades, La Vérendrye had been a linchpin in the French trade to the interior, bartering not only in furs but also in native slaves. His ambition, however, went beyond commerce to discovery. La Vérendrye, his sons, and his brother were key players in the French hunt for the Western Sea. They collected information, stories, and maps from the native peoples of the interior. They learned the niceties and frustrations of diplomacy with both Indians and crown officials. They spearheaded the establishment of French posts around and beyond Lake Superior. And they became obsessed with the “Mantanne” Indians, convinced that the “River of the West” where they lived would lead to the Western Sea. But not until 1738 did the fifty-three-year-old La Vérendrye set out for the upper Missouri.22

We know the story because an abbreviated “journal, in letter form” survives. The document does not bear La Vérendrye’s signature, nor is it written in his hand, but the authorship is clear. The manuscript, written in the first person and from his perspective, describes the significant events of his journey. Perhaps it was a clerk’s copy of a letter sent to Charles Beauharnois, governor of New France. The faded and fragile pages today reside in Ottawa, at the Library and Archives Canada.23

On October 18, 1738, the explorer departed from Fort La Reine, a French fur-trading post on the Assiniboine River some sixty miles west of modern Winnipeg. With him were not just his personal attendants—one “servant” and one “slave” of unknown origins—but also twenty hired hands, some French, some Indian. To each, La Vérendrye issued the same supplies: one ax, one awl, one kettle, one pair of shoes, two six-foot ropes of tobacco, four pounds of gunpowder, sixty lead balls, and one set of tiny gun replacement parts. There were other companions as well: a business partner and his brother, two of La Vérendrye’s sons, twenty-four Indian hunters, and an Indian guide. At fifty-two in number, it was a moderately sized expedition. It would not remain so.24

Map 4.2

La Vérendrye’s Assiniboine guide did not share the Frenchman’s eagerness to reach the Mantannes and the River of the West. The circuitous route he took lengthened the trip “by some 50 or 60 leagues,” or as much as 180 miles. “We had to consent in spite of ourselves,” La Vérendrye wrote.25 As the dismayed French commander watched “the finest fall weather slip by,” the guide led them to a large Assiniboine village. A month had already passed. On November 19, La Vérendrye met in council with “the chiefs and principal men,” who told him that the entire village, including women and children, would join the expedition. And so, with winter closing in, more than a thousand people set out across the prairie together on November 20. The departure en masse may have indicated Assiniboine awareness that enemies could attack unprotected women and children if the men proceeded without them. But another calculation was also in play. A trip to the Mandans meant trade, and as La Vérendrye reported, Assiniboine “women and dogs carry all the baggage.”26 This included not just tipis and essentials but items for barter as well.

For Frenchmen accustomed to traveling by canoe, the trek over the open, rolling terrain “never ceased to be fatiguing.” But it also filled La Vérendrye with wonder. The three-column procession, the reconnaissance of the scouts, the process of hunting along the way—all were orderly and regulated, governed by Assiniboine rules of the road. It was a marvelous spectacle, unfolding on “magnificent plains.”27

Each step brought La Vérendrye closer to the Mantannes, the River of the West, and the long-sought sea that lay beyond. His anticipation was palpable. “Everything we had heard gave us hope of making a notable discovery,” he wrote. The voyager envisioned the consummation of his life’s work. With his companions, he ran through likely scripts, speeches, and scenarios for the encounter to come.28

THE “FIRST” MANTANNE TOWN, LATE NOVEMBER 1738

The unnamed upper-Missouri town that was La Vérendrye’s destination surely buzzed with anticipation. Mandans and Hidatsas took pride in their hospitality, and they rarely passed up a chance to extend their commercial ties. Moreover, this Frenchman had cultivated them from afar for years, sending Assiniboine envoys with necklaces, presents, and promises. His arrival would be a big event.

By mid-November if not before, the villagers learned he was on the way.29 We have no eyewitness accounts of the preparations, but we can imagine. Food—dried squash, sunflower seeds, beans, and above all, corn—was the foremost priority, both for feasting and for trading.

In earth lodges throughout the town, women descended ladders into their cache pits, much as Euro-American sodbusters later descended into their root cellars for supplies during the winter. From the depths—villager cache pits could extend six or more feet below ground—came the bounty of harvests past. Desiccated ears of corn, stacked row upon row, lined the circumference of each pit. Dried squash and loose kernels filled the middle. The women extracted these items to prepare for both the guests and the opportunities on the horizon.30

NORTH DAKOTA PLAINS, LATE NOVEMBER 1738

For the Assiniboines, trekking across the prairie was old hat. This was still the pedestrian age, when northern plains denizens moved about solely by foot or by boat. Horses were about to burst onto the scene—in fact, some may have already visited the upper-Missouri towns—but for now, La Vérendrye’s guides traveled just as their ancestors had for millennia.

The Frenchmen learned by watching the Indians. Where, for example, does a traveler get firewood when crossing a sea of grass? The only sources La Vérendrye saw were “islands of timber” that were few and far between. In this horseless world, you therefore lugged your fuel with you. The Assiniboines made “the dogs carry wood for fires,” La Vérendrye reported, since they “frequently” had “to camp in open prairie.”31

There was another solution too, which the explorer had only heard about before his trip: Desiccated bison dung was a useful fuel. From the Sudan to the Anatolian Plateau to the Mongolian steppe, human beings have warmed their hands, cooked their food, and fired their pots over animal-dung flames for thousands of years. Collecting dung may in fact be less laborious than gathering and chopping wood. According to the trader Alexander Henry, bison chips were “the common fuel” of the northern plains. In 1806, on a journey with a large party of Hidatsas, he described settling in “for the Night with upwards of three hundred Buffalo Dung fires smoking in every direction around us.”32

Bison-chip fires were not just for food preparation and heat. They also put off clouds of thick smoke that drove away “the numerous swarms of Misquetoes” that plagued plains travelers in the summer. Dried and pulverized dung could even serve as tinder. When the painter George Catlin sat down to smoke a pipe with the Mandan chief Four Bears in 1832, the Indian drew “from his sack a small parcel containing a fine powder, which was made of dried buffalo dung.” This he sprinkled “like tinder” over the willow bark in the bowl so the pipe would light “with ease and satisfaction.”33

For all its convenience, dung fuel did have drawbacks. One was that it yielded only half the heat of firewood. This was at least in part because bison-dung ash, instead of falling away from the burning pile, accumulated and clung to it, curtailing the output of radiant energy. Most native groups learned to augment paltry heat production by encircling dung fires with rocks, a practice not followed when burning wood.34

Dung had another drawback: Its smoke flavored any meat cooked directly over it. In July 1806, Alexander Henry and his companions shot a bull bison below the Souris River loop in what is now North Dakota. They anticipated a “hearty supper.” But their hopes were dashed when the only dung they could find was “very damp.” They had no kettle, and were dismayed to find that the flame-roasted flesh took on “a very disagreeable taste of the dung.” The English adventurer Sir Richard Burton viewed the problem with more humor when he traveled across the prairies in 1860. “A steak cooked” over bison chips, he said, “required no pepper.”35

ON THE NORTH DAKOTA PLAINS EAST OF THE MISSOURI RIVER, NOVEMBER 28, 1738

The day had come. “On the morning of the twenty-eighth we reached the place chosen for meeting the Mantannes,” La Vérendrye wrote. This was not the Mantanne town itself but a camp the travelers set up at a distance, some four days away. By Indian protocol, they remained there until dignitary-envoys came to greet them. The wait seemed interminable, but “toward evening” they came: “a chief with thirty men.”36

La Vérendrye was surprised. His conversations with the Crees and Assiniboines—inflected, perhaps, with wishful thinking—had led him to expect a people with beards, white skin, and light hair, a people who walked “with their toes turned out” like Frenchmen and who wore “a kind of jacket with breeches and stockings.” Instead, the Mantanne chief and his entourage seemed “not at all different from the Assiniboins; they go naked, covered only with a buffalo robe carelessly worn without a breechcloth.”37

The Frenchman’s heart sank. “I knew by this time that we would have to discount everything we had been told about them.” Speaking through interpreters, the Mantanne chief told La Vérendrye that his nation resided in six towns, or “forts,” and that his was the only one not located beside the river. It was also smaller than the others. But the chief nevertheless hoped the voyager would make himself at home.38

The chief eyed La Vérendrye’s Assiniboine entourage. Its huge numbers would tax Mantanne hospitality: “This would entail a great consumption of corn, their custom being to provide food freely for all who visited them.” With this in mind, the chief “played a trick on us,” La Vérendrye said, admitting that he fell for it himself. Feigning relief, the headman professed gratitude for the expedition’s arrival. The timing was perfect, he said. Sioux warriors—enemies of La Vérendrye, the Assiniboines, and the villagers alike—were lurking nearby. Now they could take them on together.39

The news put the Assiniboines in a dither. They did not want to fight the Sioux. A council convened. What could be done? The council’s decision served Mantanne interests perfectly: With a suitable guard, the Assiniboine women and children stayed behind, avoiding the purported Lakota threat. The men and La Vérendrye, only six hundred in all, went to the town.40

They headed out on the morning of November 30, tramping through spent stalks of needle- and wheatgrass. The surviving account describes neither landscape nor weather. But the hummocks and potholes that mark the swelling land formation we call the Missouri Coteau—the geographic endpoint of Pleistocene glaciation in this part of the world—make for challenging transit under any conditions. And when November turns to December, winter sets in on the North Dakota prairies. Winds blow out of the northwest, and mean temperatures dip below 20 degrees Fahrenheit.41

After four days of walking, they came to a stop with fewer than five miles to go. A crowd of townspeople who had come to greet them had set up a great outdoor banquet in the open country, with fires warming pots of pumpkin and squash. It was La Vérendrye’s first taste of villager hospitality. There was “enough food for all of us,” he marveled. Seated beside two chiefs, he ate and smoked and took in the scene.42

They rested for two hours. Then, with the town just ahead, the fur trader ordered his son to the front, French flag in hand. La Vérendrye got to his feet to follow, but the Mantannes demurred. They “would not allow me to walk,” he wrote, “but insisted on carrying me.”43

They stopped again with the village in view. A “party of old men” accompanied “by a great number of young men” awaited them. They presented the French commander with the calumet and showed him the necklaces he had sent to them years before. Crowds of natives watched from rooftops and from the earthworks outside the palisade. La Vérendrye had his companions line up in a row—first Frenchmen, then Assiniboines with muskets. They fired a three-shot volley and, French flag at the fore, entered the Mantanne town at 4 p.m., December 3.44

In the early twenty-first century, the location of the village that La Vérendrye entered is still a mystery. Indeed, some have associated it not with the Mandans but with the Hidatsas, whose northerly position put them a few miles closer to the French and their Assiniboine escorts.45

THE “FIRST” MANTANNE TOWN, DECEMBER 3–5, 1738

The first three days were a whirlwind of trading, feasting, and speech-making. La Vérendrye summarizes the events briefly, barely pausing to describe the Mantannes or their town. His principal concern was that his supply of presents—all the goods he had brought with him—had been stolen. The identity of the thief was not known: The Assiniboines blamed the Mantannes, and the Mantannes blamed the Assiniboines.46 Regardless of the culprit, the Frenchman was at a loss. He knew that generosity fostered commerce and diplomacy, that gifts indicated affection, good intentions, and abundant resources. Yet he had nothing to disburse. A measly presentation of powder and shot was the best he could do.

Luckily, the Mantannes surmised his intentions. In a series of speeches, they assured him that as long as he stayed, he would never go hungry, that “they had food in reserve.” They told him to consider himself “master” of the town. “We pray,” one chief added, “that he will number us among his children.” La Vérendrye, no stranger to plains rituals, grasped the import of this request. Adoption was the central rite of the calumet ceremony. Putting his “hands on the head of each chief,” he embraced each as his son. His Mantanne hosts “responded with great shouts of joy and thanks.”47

Although the Frenchman did not have anything to trade, the Assiniboines did. La Vérendrye watched the exchanges closely, learning much about a commerce he had only heard about before. The nomads had become long-distance brokers of manufactured goods, purchasing them at French or English posts, ferrying them south, and selling them in the villages. The Assiniboines had brought not only bison products but also “muskets, axes, kettle[s], powder, ball, knives, and awls to trade.”48

The Mantanne offerings were traditional: dried maize, tobacco, bison hair, and an assortment of handicrafts the Assiniboines found irresistible—“garters, head bands, and belts” as well as “painted buffalo robes” and “hides of deer and antelope, well dressed and decorated with hair and feathers.” The Mantannes dressed “hides better than any other people,” La Vérendrye said, and they did “work in hair and feathers very pleasingly.”49

With their access to metal and manufactured goods, it seems logical that the Assiniboines might have had an advantage in the trade. But as La Vérendrye saw it, this was not the case. The Mantannes, “sharp in trading,” were “stripping the Assiniboins of all they possess.” The Assiniboines were “always being cheated,” and the villagers were “craftier in trade, as in everything else.”50

Figure 4.1. Mandan moccasins decorated with quillwork. Collected by Clark Wissler.

It is hard to know what to make of these statements. The Mandans and Hidatsas lived and worked at the commercial vortex of the northern plains. The constant flow of people and merchandise over generations had given them invaluable experience in the art of barter, while the Assiniboines may have been like tourists at a foreign marketplace today, naïfs caught in unfamiliar circumstances. Also, the Mantannes probably had alternative sources for the bison products, if not the European wares, that the Assiniboines brought to the table, an advantage that surely enhanced their bargaining position. La Vérendrye also may not have understood how differently the natives might value goods, especially European goods; he may have held the European items in unduly high regard. And the buildup to his trip across the plains had been enormous. Primed with the idea that the Mantannes were “white in colour and civilized,” he might have believed them “craftier” due to his own notions of racial superiority.51

THE “FIRST” MANTANNE TOWN, DECEMBER 6, 1738

The villagers took pride in their hospitality, but enough was enough. They had entertained six hundred guests for three days. “Seeing the great consumption of food made each day by the Assiniboins, and fearing that they might stay a long time, the Mantannes started a rumor that the Sioux were near and that several of their hunters had seen them,” La Vérendrye explained.52

But as the Assiniboines made haste to flee, a Mantanne chief, “by a sign,” indicated to La Vérendrye that the story was a ruse. So the Frenchman told his former escorts he would stay and presented a gift to their headman to reassure him of his friendship. La Vérendrye did not realize that the Assiniboine exit was a crisis in the making.53 It was probably his son who told him it meant they had lost their interpreter.

Communication in widely varied languages was problematic for colonial enterprises everywhere. And of course it also posed problems for indigenous groups interacting among themselves. La Vérendrye’s solution had been this: He would speak in French to his son, who was fluent in the language of the Cree Indians and could transmit the message to “a young man of the Cree nation who spoke good Assiniboin”; the Cree man would then speak to the “several Mantannes” who also knew Assiniboin, and these Mantannes would translate the message into the tongue of their own people.54 The Mantanne response would require reversing the chain of translation.

This complicated system, like a long game of telephone, was rife with opportunities for error. But to a French-speaking voyageur who came of age in the fur trade, such problems came with the territory. La Vérendrye described his Mantanne translation system with indifference. “Thus,” he said, “I could easily make myself understood.”55

Yet he could not make himself understood if the chain lost a link. This is exactly what happened when the Assiniboines left the Mantanne town on the morning of December 6, La Vérendrye’s Cree interpreter with them—departing, La Vérendrye noted, despite being “paid well” and despite “all the offers” made to keep him. The interpreter “had become enamored” of an Assiniboine woman who refused to stay among the Mantannes. It was an event “to crown our misfortune,” as La Vérendrye put it.56

For the rest of their stay, the Frenchmen “were reduced” to making themselves “understood by means of signs and gestures.” Plains sign talk could achieve fluent conversation when used by skilled practitioners, but La Vérendrye and his French-speaking companions were not proficient, and communication foundered. This is why he chose two men “capable of learning the language of the Mantannes quickly” to stay behind when he left.57

THE “FIRST” MANTANNE TOWN, DECEMBER 13, 1738

After ten days at the Mantanne settlement—with darkness closing in and with neither an interpreter nor gifts to sustain diplomacy—the voyageur chose not to winter over or proceed farther. “We decided that we must go,” he wrote. He ordered his men and the few remaining Assiniboine guides to get ready for a December 11 departure.58 But when the day came, La Vérendrye could not move. He was “very sick” in bed, confined to an earth lodge.

Not until December 13 did the party set out, and even then his infirmity persisted. The return trip, undertaken in the dead of winter, was miserable. The cold was intense, the terrain difficult, and La Vérendrye’s bad health unrelenting. It took two months of slogging against the wind for the men to reach Fort La Reine, where they arrived on February 10, 1739. The exhausted commander summed it up tersely: “Never in my life have I endured so much misery, sickness, and fatigue as I did on this journey.”59

For the plains townspeople, the La Vérendrye visit was at once mundane and extraordinary. The Mantannes regularly welcomed guests from afar, but the Frenchman and his entourage were not just another trading party. They represented a new commercial opportunity and a way to bypass Cree and Assiniboine intermediaries. In years to come, with more and more non-Indian traders visiting the upper-Missouri towns, the nomad Assiniboines surely regretted their decision to guide La Vérendrye across the plains. The records are sparse for the early years, but come the newcomers did, under French, British, and eventually Spanish and American flags. The era of sustained contact was under way.