FIVE

Customs: The Spirits of Daily Life

UPPER-MISSOURI VILLAGES

Pierre de la Vérendrye and his companions had encountered a people blessed with material abundance. “Corn, meat, fat, dressed robes, and bearskins” were all among their riches. “They are well supplied with these things,” the Frenchman wrote. But his abbreviated journal barely mentions the villagers’ equally rich ceremonial life.1

Luckily, ancient town sites and the stories surrounding them reveal what early documents do not. Even Huff and Shermer, two villages that date to the 1400s, had telltale plazas and medicine lodges. These features suggest that the most prominent aspects of ceremonial life that participants and eyewitnesses described after 1800 were in place centuries earlier.2 It is impossible to say what the first rites looked like or how they evolved in the intervening years, but one scholar has deemed the Mandan Okipa “without question, the most elaborate, complex, and symbolic ceremony performed on the Northern Plains.”3 So compelling was the Okipa that it may well have shaped the development of the famed Sun Dance among other plains peoples.*

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, JUNE 25, 2009

Mih-tutta-hang-kusch sits on a high bluff on the west side of the Missouri River, twenty-eight miles northwest of Double Ditch. The Mandans lived here for a brief fifteen years, from 1822 to 1837. The town and its neighbor, a much smaller village nearby, were the last distinctively Mandan settlements on the upper Missouri River. Here the occupants carried on as their ancestors had for centuries: farming, hunting, and trading.

They also performed the Okipa, the four-day ceremony that brought good things to the Mandan world. The Okipa had momentous implications: It restored balance. It evinced love for the spirits. It affirmed female ascendancy. It brought bison herds near. It helped gardens grow. It transmitted history, power, and wisdom from one generation to the next. It was the very essence of being Mandan.

Mandan spiritual life was fluid. It evolved continuously, embracing new practices, spirits, and ceremonies as they emerged and abandoning others when they outlived their sustainability or usefulness. The Okipa, for one, was supposed to change with the people themselves. Ceremonial variants even demarked Mandan subgroups. The Awigaxas, for example, relied on traditional corn rites and did not adopt the Okipa until the 1700s. Adaptability, ironically, created continuity. It allowed the Mandans to preserve their identity in the face of change, both before and after 1492.4 It would therefore be disrespectful—even treacherous—to ignore the spiritual dimensions of Mandan life. “Our true nature is spiritual,” my Mandan friend Cedric Red Feather tells me again and again.

Cedric’s words run through my mind as I walk through the grass at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch on a perfect June day. The Missouri River is the most surprising feature here. Home of the water spirit Grandfather Snake, it once cut away at the bank directly below the town.5 But in the early twenty-first century, the river is nowhere to be seen. Instead, tree-covered bottomlands testify to its temperamental nature and ever-changing course. It now flows in the distance, a mile or so beyond the branches of willow, box elder, cottonwood, and ash that tangle the flood plain below.

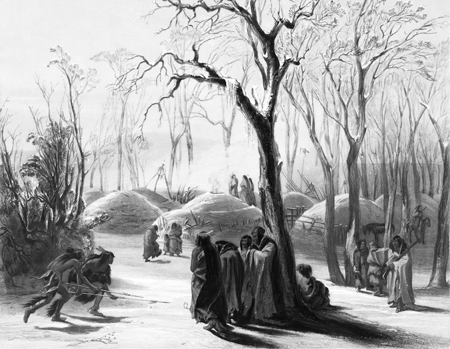

Figure 5.1. Bison-dance of the Mandan Indians in Front of Their Medecine Lodge in Mih-Tutta-Hankush, aquatint print (after Karl Bodmer) of a dance of the Buffalo Bull Society. Bodmer and Maximilian witnessed this dance on April 9, 1834. It was either a special performance or an event associated with the spring meeting of the society.

I walk northwest along the edge of the bluff. My imagination conjures up the maps and paintings I’ve seen of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. The ceremonial plaza, I know, was on this side of the town. I look in the grass for clues among the circular depressions that mark former earth lodges. There is open space to my left. I turn away from the bluff and walk a short distance to what I imagine was the center of the plaza. Was this it? I am not sure. If it was, Lone Man’s sacred shrine—the focus of the Okipa and the embodiment of Mandan history—once stood close-by.

Figure 5.2. A Mandan shrine on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation near Crow’s Heart’s Lodge, 1909: a sacred cedar representing Lone Man within a plank corral. Crow’s Heart built a traditional earth lodge and shrine on his land after the federal government forced the Mandans to take up allotments in the 1880s, and his home became a favorite gathering place for Mandans.

The Okipa had serious work to do at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. The ongoing “Columbian Exchange” wrought by generations of Atlantic voyages after 1492 had brought new people, technologies, animals, and diseases to the upper Missouri River. But in the face of upheaval, the Okipa was a steadying force. It was a time when “everything comes back” and the past reasserted itself.

FORT BERTHOLD INDIAN RESERVATION, 1929–31

One of the most remarkable sources of information on Mandan ceremonial life is the work of an anthropologist named Alfred Bowers. As a graduate student doing doctoral research at the University of Chicago, he visited North Dakota’s Fort Berthold Indian Reservation repeatedly from 1929 to 1933, immersing himself first in the world of the Mandans and then in the world of the Hidatsas. Bowers had grown up nearby and had a knack for learning languages. He developed a deep rapport with his Indian informants, among them a Mandan man named Crow’s Heart. Like most of the Mandans who gave Bowers information during these years, Crow’s Heart was already quite old. By 1947, when he met with Bowers again, he was the only informant still alive. Together, at this 1947 meeting, Crow’s Heart and Bowers recorded the older man’s autobiography and revised the younger man’s doctoral dissertation to make it a publishable book. It was probably during these discussions that Crow’s Heart explained how he came to trap fish.

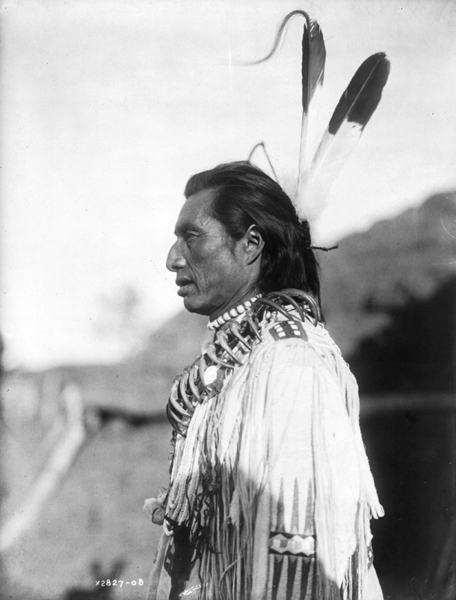

Figure 5.3. Crow’s Heart—Mandan, photograph by Edward S. Curtis.

Crow’s Heart grew up in a village called Like-a-Fishhook. He decided as a young man that he wanted to trap fish. The preparation took years, so he was nearly thirty when he finally approached Old Black Bear about the matter. Crow’s Heart invited the older man to his family’s lodge, where he seated him on a new bison robe and wrapped him in a thirty-dollar overcoat. Crow’s Heart’s wife served the old man “a feast of meat, bread, and coffee.” Gifts of “a good gun, a fair horse, a redstone pipe, a good butcher knife, and three or four pieces of calico” followed.6

The outpouring prompted Old Black Bear to ask him, “What’s up? What’s all this for?”

“I want you to do me a favor. I want you to give me the right to make a fish trap,” Crow’s Heart said.7

The deal was made. In return for the feast, robe, gun, horse, and other items, Old Black Bear taught Crow’s Heart how to build a fish trap, where to put it, and how to pray when he did so.8 Crow’s Heart had purchased fish-trapping rights.

Buying and selling were at the heart of Mandan life. Most of the villagers’ sacred rites—the corn ceremonies, the buffalo-calling ceremonies, the eagle-trapping ceremonies—were bought, sold, and transferred among individuals. Restrictions pertaining to clan, kin, gender, or birth order might apply, but otherwise, the main limits were desire and available resources.

Figure 5.4. Black Bear inside a fish trap using a fish basket.

The sacred rituals were embodied in what were called medicine bundles. The Robe bundle, for example, conferred corn ceremony rights to its owner. It contained seventeen different objects, including ears of corn, a gourd rattle, a fox-skin headdress, and a robe and pipe that once belonged to Good Furred Robe, the ancient chief who had taught the Mandans how to plant maize.9

Someone who wanted all the rights associated with a bundle could approach the owner and arrange to buy it, so long as the transfer followed the appropriate rules of inheritance. But bundles were expensive. Sometimes a person wanted only selected rights from a bundle owner, a cheaper proposition. This was Crow’s Heart’s intention. Old Black Bear owned an eagle-trapping bundle that also conferred fish-trapping rights, and a “secondary bundle” for these rights was what Crow’s Heart desired.

The purchase of a bundle called for more than the assembly and transfer of sacred objects. It required the transfer of knowledge. Individuals buying bundles had to learn all the associated rites, privileges, songs, stories, obligations, and traditions. And they also, for the good of the people, had to perform the accompanying ceremonies regularly.

Mandan children learned at a young age that rights and knowledge had value. Bowers noted that elders expected children to offer some token—perhaps “a small colored bead or a few kernels of corn”—in exchange for instruction. Even innate talents required purchase before use. One might have a natural gift for singing, hunting, or pottery making, but engaging in these pursuits without buying the rights to them was “ill mannered.” It drew bad luck as well.10

Sellers, for their part, did not lose rights when they passed them on to others. Each bundle owner could sell rights four times.11

The objects inside a bundle contained xo′pini, or power, an attribute that accrued to the owner. But the tribulations of daily life took a toll on this potent, protective, and invigorating force. Individuals lost xo′pini “a little at a time,” Bowers learned. “Crossing rivers, hunting buffaloes, training horses,” and other perilous activities made for a cumulative depletion, and constant renewal was required. The restoration and accrual of xo′pini came through kindness and generosity, through fasting and self-sacrifice, through the purchase of sacred bundles, and especially through Walking with the Buffaloes, the sacred ceremony in which women initiated the transfer of power from old men to younger men via sexual intercourse.12

Thus a person’s sacred bundles mattered in part for their xo′pini, which instilled power and humility at once. The dynamics were simple: “I claim no power for myself,” Bowers wrote. “I have no power except what my sacred objects have promised me.”13 But beyond xo′pini, bundles conferred status and responsibility. Villagers expected their owners to perform their associated rites and to use them for the good of the people. Holders of the most prestigious bundles, such as those associated with stories of the tribe’s origins and the Okipa, were esteemed in accordance with their bundles. Since bundle ownership was in many cases hereditary, this meant that among the Mandans, status too could be inherited. The most prominent families lived closest to the ceremonial plazas in their towns.14

The Mandan practice of buying and selling rites, ceremonies, knowledge, feasts, songs, bundles, and instruction may seem strange at first. But familiar analogies are numerous. Think of the nuances of copyright law, the exclusiveness of craft guilds, the benefits of a college education, or the acquisition of indulgences from the Catholic Church, all of which confer socially sanctioned rights or privileges. All come at a price.

Other upper-Missouri nations had traditions like those of the Mandans. The Arikaras, for example, at one time sold their Hot Dance ceremony to the Mandan Crazy Dog Society.15 All these peoples—Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras—earned renown for their marketplace prowess. It is possible that cultural ease in buying and selling made them particularly well suited for commercial undertakings.

LIKE-A-FISHHOOK, NORTH DAKOTA, WINTER 1861

Ceremonial life both prevented crises and averted them. An incident at Like-a-Fishhook, a combined Mandan-Hidatsa village, was a case in point. It took place in the winter of 1861.

The crisis was a shortage of meat. Bison were nowhere to be found. There was corn, of course, but that fare was neither satisfying nor viable over months at a time. The fur trader Henry Boller, who lived in an earth lodge at the neighboring fort, complained that he had consumed nothing but coffee and parched corn for three days. “Something must be done,” he wrote.16

The men of Like-a-Fishhook tried first. A Hidatsa chief called Four Bears bent his spiritual powers to the task, but according to Boller, he could not “dream right.” A man named Red Cherry tried next. He climbed the highest butte outside the town and fasted there through three days of winter weather as scouts watched from hilltops to spot the beasts. Alas, there were none.17

Eventually the Mandan White Buffalo Cow Society stepped in. One of Bear Hunter’s five wives—elderly, lame, and blind in one eye—sent boys out to spread the news that the dancing was to begin the next night. A wave of relief swept Like-a-Fishhook. The White Buffalo Cows’ medicine never failed.18

The old women assembled, one by one, forty or fifty in all. One wore the robe of a white buffalo. Each had “a spot of vermilion on either cheek.” As villagers watched and musicians filled Bear Hunter’s earth lodge with songs and drumming, the women began to dance. They danced day and night for a week, barely stopping for breaks as the crowd grew. Then one afternoon “an unearthly clamor” erupted “among the dogs” outside. Boller rushed from the lodge with the rest of the spectators.19

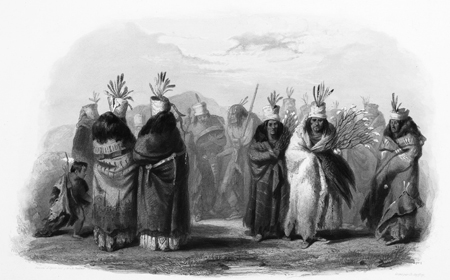

Figure 5.5. Ptihn-Tak-Ochatä, Dance of the Mandan Women, aquatint print (after Karl Bodmer) of a dance of the White Buffalo Cow Society.

“Strong medicine!” he reported. “A huge buffalo bull was charging wildly about, not twenty yards from the lodge wherein the White Cow band were dancing!”20 The White Buffalo Cows had done their work.

Boys, girls, men, women—all Mandans and Hidatsas over the age of twelve had their age-based societies. The White Buffalo Cows were just one of them. Membership was not mandatory, but purposeful attachment to an age-grade society was an emblem of citizenship, an acknowledgement of duty, obligation, and the proper order of things. “It was like a deep trail,” one informant told Alfred Bowers; “one had to follow the same path the others before had made and deepened.”21

For young boys and girls, age-grade associations introduced affinities outside their parental earth lodge. Pubescent Mandan boys who wanted membership in the Magpies or Stone Hammers trained under adoptive fathers who came from their own fathers’ clans but lived elsewhere in the village. With the help of their sponsors and their own family members, the youths worked diligently to gather the goods—food, handicrafts, bison robes, blankets, weapons, or utensils—needed to buy the rights they sought. Their initiation involved fasting, and so did their long-term obligations. Stone Hammers regularly fasted for spiritual intervention during a village’s ceremonial events.22

Similarly, adolescent Mandan girls joined the Gun Society or the River Society under the sponsorship of adoptive clan mothers. Girls buying into the River Society saved up food and other property for payment and spent four successive nights dancing with their peers in a designated earth lodge. Each night the initiates presented kettles of food to their society mothers, then slept beneath eagle-feather headbands suspended from the rafters. On the last night, they were given new sets of clothes made by their sponsors.23

The societies graduated sequentially as age, desire, and purchasing power accumulated. They also changed over space and time. The Gun Society arose only after firearms became available. The Black-Tail Deer Society existed solely on the west side of the Missouri; the smallpox of 1837 eradicated it entirely. Much of our information about these societies comes from Hidatsas whose ancestors purchased them from the Mandans after the tribes consolidated at the Knife River.24 Innovations and adaptations were common.

Our knowledge of these groups may be cobbled together, but the most prominent cohorts are clear. For childbearing women, they included the Goose Society, whose thirty- to forty-year-old members summoned good weather for the spring planting season. Their menstrual flows were believed to ensure fertile gardens and to frighten bison away. The postmenopausal White Buffalo Cows, on the other hand, could draw winter weather and, with it, the bison to the river bottoms. Their powers required respect. So potent was their medicine that mere mention of the group before the harvest was in could bring an early frost.25

The prominent male societies included the Black Mouths, middle-aged men charged with policing the village. They wore distinctive ceremonial face paint: upper half red, lower half black. The Black Mouths were among the most active groups, meeting every two or three days and taking orders from the more senior Buffalo Bulls, the male analogues to the White Buffalo Cows. These old men were flush with accumulated wisdom. Most had led war parties, hunted bison, broken horses, and taken other risks in their younger years, expending much power, or xo′pini. But now that they were old and no longer lived lives of danger, they could share their wisdom and their xo′pini with others. And like the old women, they could call the buffaloes.26

TOBACCO ON THE UPPER MISSOURI

For the Mandans as for most Native Americans, tobacco was a central part of daily and ceremonial life. According to tradition, tobacco came to Lone Man and First Creator by way of the buffalo. One of Alfred Bowers’s informants told the tale: When Lone Man and First Creator told the buffalo that “they did not know what the tobacco was,” the animal urinated “in spots” that soon brought forth Nicotiana quadrivalvis—Mandan tobacco. The buffalo showed the two culture heroes how to prepare and smoke the plant in a pipe that represented the west and east sides of the Missouri River. The bowl, like the west side of the river, was feminine; the stem, like the east side of the river, was masculine. Only the river kept the two sides apart.27

Tobacco’s usefulness was spiritual, social, and ceremonial. Its wafting smoke and psychoactive effects connected its users to one another and to the spirit world. When the Mandans adopted the calumet ceremony in the seventeenth century, it helped them create ties of fictive kinship with strangers. But tobacco’s service was not limited to the pipe. “It is conceivable,” notes one anthropologist, “that as much Nicotiana was cast into fires, water, and rock crevices during tobacco invocations as was consumed by smoking.” Invocations summoned spirits, venerated them, and acknowledged the unending compact between earthly and supernatural worlds. Similar offerings affirmed implicit compacts between people. In November 1738, when the Mandans met Pierre de la Vérendrye for the first time, they presented him with “Indian corn in the ear and a roll of their tobacco.”28

The tobacco drew La Vérendrye’s attention, not for its meaning but for its taste. It “was not very good,” he said, because the Mandans were “not familiar with preparing it as we do.” The Mandan plant was “cut green, everything being used, blossoms and leaves together.” Other observers said there were times when the Indians smoked only the blossom, “dried before the fire upon a fragment of an earthen pot.” Most Europeans did not like the flavor. “I find the flowers a very poor substitute for our own Tobacco being only a mere nauseous insipid weed,” wrote the trader Alexander Henry. The German Prince Maximilian was more measured. To him, the upper-Missouri plant was “somewhat unpleasant.” The Mandans in turn found “European” tobacco “too strong.”29

Upper-Missouri townspeople flavored their tobacco and extended its usefulness by mixing it with other substances—dogwood bark, bearberry, bison tallow, and possibly sumac and willow.30 Beaver castor, shaved from the animal’s scent glands, also found its way into Mandan pipes.31 All these blends fell under the general name kinnikinnick, smoked by Indian peoples across the continent.

The important distinction between Mandan tobacco and that smoked by Europeans was that they were in fact different species. All tobacco has American roots, and by the time the French encountered the Mandans, its consumption and cultivation had spread around the world. But upper-Missouri tobacco was not Nicotiana tabacum, the domesticated species that dominated international markets. It was N. quadrivalvis, a plant that flourished in the wild as well as in gardens. The upper-Missouri species was less potent—with 40 percent less nicotine—than the N. tabacum in global circulation.32

In a world where women had nearly exclusive rights to the tasks and ceremonies of agriculture, Nicotiana was an outlier. It was planted by men, especially older men, not just among the Missouri River tribes but also among the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands. In fact, tobacco cultivation may have emerged separately from other forms of indigenous gardening, for unlike maize, beans, squash, and sunflowers, tobacco was not a foodstuff.33

There was a reason that tobacco cultivation fell to the older men. Young men “used little tobacco, or almost none” outside ceremonial circles. As Buffalo Bird Woman explained, her people knew “that smoking would injure their lungs and make them short winded so that they would be poor runners.” This was not just a matter of winning village games and footraces; it was a matter of survival. In the days before the horse, hunting and military pursuits took place on foot. “A young man who smoked a great deal, if chased by enemies, could not run to escape from them, and so got killed,” she said. “For this reason all the young men of my tribe were taught that they should not smoke.” Only men whose “war days and hunting days were over” engaged in leisurely smoking.34

Buffalo Bird Woman made these comments between 1912 and 1915, fifty years before the United States Surgeon General released Smoking and Health, the 1964 bombshell that directed worldwide attention to the gruesome effects of tobacco consumption. Apparently those who knew the effects of tobacco best were those who had used it much longer than the latecomers who took up its consumption after 1492. Small wonder. But even as Buffalo Bird Woman described the old ways, Indian habits were changing. “Now young and old, boys and men, all smoke,” she said. “They seem to think that the new ways of the white man are right; but I do not.”35

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, JULY–AUGUST 1832

“I have this day been a spectator of games and plays until I am fatigued with looking on,” wrote George Catlin during a summer sojourn at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch in 1832. We do not know the day to which the painter referred—he rarely recorded precise dates—but it was probably in July. Catlin’s stay began in July and extended into August, when the green corn harvest would have preoccupied the Indians.36

Catlin found that sports and gambling were a Mandan obsession, engaging the Mandans every bit as much as they engage Americans today. One sport was the “game of the arrow,” in which men with bows shot arrows skyward in rapid succession, vying to get as many as possible aloft at one time. The best contestants “had been known to get ten arrows in the air.” And there was the Mandan equivalent of what many know as “Hacky Sack,” trademarked today by Wham-O but played for centuries by peoples around the world. Mandan women played their version of this game with “a thick leather ball” that they let “fall alternately on foot or knee,” said Prince Maximilian, the object being to keep it aloft “for a long time” without letting it “touch the ground.”37

There were footraces too. A Catlin painting of a Mandan running match shows throngs of gathered spectators. The fur trader Alexander Henry reported that such contests took place “almost every day” during the summer, on a course that, by his reckoning, covered six or more miles. “This violent exercise is performed on the hottest summer days,” he observed. The starting point was a “beautiful green” near the village, from which the runners set out “in a file on a slow trot, intirely naked,” following a road into the hills and disappearing. Eventually, they reappeared at a sprint, coming “down a steep hill” and returning to their starting point, where, instead of stopping, they rushed “headlong” into the Missouri River, “whilst they are all covered with dust and sweat.” Henry marveled at the speed of the fastest competitors.*

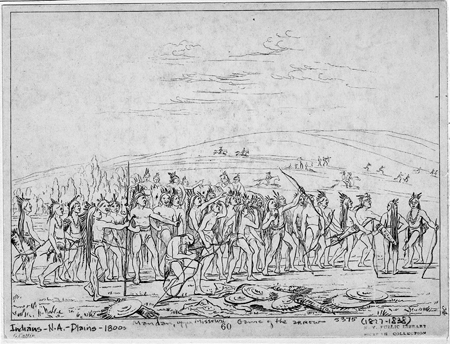

Figure 5.6. Mandan men playing the game of the arrow, by George Catlin.

A year after Catlin’s visit, the fastest Mandan runner proved to be an eleven-year-old named Bear on the Water. A report based on a 1904 interview with the aging former athlete described him as “the most famous runner in the whole Missouri valley; he was accustomed to hunt and catch antelope on foot and in the same way overtake and shoot buffalo.”38

Horse racing was another Mandan enthusiasm, once the animals became common in the eighteenth century. George Catlin found Mandan horse races “thrilling”—one of their “most exciting amusements”—and painted a picture of a contest under way.39 Alexander Henry heard about a horse race from his men, though he did not get to see it himself. The riders “set out pell mell,” he reported, “whip[p]ing and kicking their Horses all the way.” They covered “a long circuit,” and on their return “performed their Warlike maneouvre on horse back,” feinting “attacks upon the enemy, parrying their strokes of the Battle axe, Spear &c.”40 The scene captivated North West Company fur traders in 1806 as much as it thrilled Catlin years later.

Figure 5.7. Bear on the Water and his wife, Yellow-Nose. Bear on the Water was at one time the “swiftest runner” in the Mandan tribe. On the night of the famous meteor shower of 1833, “he had been running all day and so was not wakened when every other occupant of the village was awake and panic struck at the sight of the falling meteors.” He survived the smallpox epidemic of 1837 and went on to become a spokesman for his people.

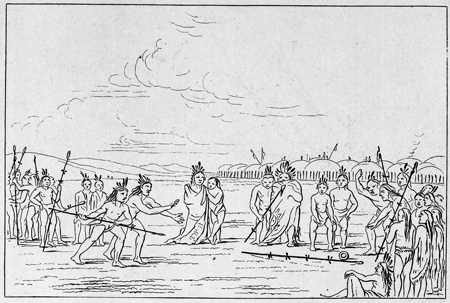

Entertaining though they were, none of these diversions matched the sport of tchung-kee. Young Mandan men practiced tchung-kee the way young American men today practice spin dribbles, dunks, and jump shots.41 “This game is decidedly their favorite amusement,” Catlin wrote. “They seem to be almost unceasingly practicing whilst the weather is fair, and they have nothing else of moment to demand their attention.” In fact, the villagers played tchung-kee in good weather and bad. Catlin painted the Mandans engrossed in it in the summer. The Swiss artist Karl Bodmer painted the Hidatsas hard at play in the winter. Three of Lewis and Clark’s men witnessed a Mandan contest on a “cold & Stormy” day in mid-December 1804. It was “a game of great beauty and fine bodily exercise,” Catlin said, but also “very difficult to describe.”42

Native Americans played versions of tchung-kee all across the continent. “The warriors have another favourite game, called Chungke,” wrote the trader James Adair of Mississippi’s Choctaw Indians in 1775. The Navajos of Arizona called it “Nanzoz.” The Senecas of New York knew it as “gah-nuk-gah.” California’s Mariposan Indians called it “xalau.” And the Kwakiutl of British Columbia referred to it as “kinxe.”43 Although the contest varied in details from one nation to the next, it almost always involved throwing a stick or shooting an arrow through a rolling hoop of some kind.

The Mandan version was nuanced. It took place on a special field fifty yards long and five paces wide, “as smooth and hard as a floor.” The contestants were men. For each round, two players set off running side by side down the length of the field. Both carried tchung-kee sticks, six feet long with little spines of leather attached at each end and the middle. Near the field’s midpoint, one player rolled a small, doughnut-shaped stone, two or three inches in diameter, ahead of them. Now, as they continued running, each participant threw his tchung-kee stick, sliding it forward on the ground beside the rolling ring of stone. The aim was to launch the stick so that when the stone finally tipped over, it impaled itself on one of the projecting spines of leather. Scoring was complicated. Players earned points, Catlin said, “according to the position of the leather on which the ring is lodged.” The winner of each round got to roll the stone for the next one—the equivalent of the “make it, take it” rule in street basketball. The game was a Mandan obsession. “These people become excessively fascinated with it,” Catlin wrote.44

Figure 5.8. Game of Tchungkee, by George Catlin. Catlin said it was “the great and favourite game of the Mandans, and of which they seem never to get enough.”

The Mandans also loved to gamble. Rare was the contest—archery, tchung-kee, horse racing, or some other—unaccompanied by a wager. “Their amusements are gambling after the manner of the Indians of the Plains,” said the Canadian David Thompson in 1798. An ancient Mandan story describes two tchung-kee rivals playing with snake-charmed sticks for ever-escalating stakes. The wagered objects include wives, earth lodges, and the very bedclothes of a contestant’s parents. Hacky sack too was played for stakes, as women executed as many as a hundred passes in their efforts to claim the “prizes” laid down. Competitors in a game of the arrow staked “a shield, a robe, a pipe,” and other articles on the outcome. The winner took all. Catlin called Mandan betting on horses one of their “most extravagant modes of gambling.” He even claimed to have seen tchung-kee bettors lose “every thing they possess,” at times staking even “their liberty upon the issue of these games, offering themselves as slaves to their opponents in case they get beaten.”45 The painter may have exaggerated, but Mandan gaming impressed him deeply.

Figure 5.9. Winter Village of the Minatarres, an aquatint print (after Karl Bodmer), showing Hidatsas playing tchung-kee.

EAGLE NOSE BUTTE

For Mandans, the landscape itself was a sort of winter count, marking the stories and events that made them a people.46 Eagle Nose Butte, on the west bank of the Missouri a short distance above Huff, was one site that did exactly this.

The story of Eagle Nose Butte goes back to early times, when the ancestral Mandans lived farther east, near a lake. Here they encountered a chief named Maniga, head of a troublesome set of strangers who controlled access to valuable shells that the Mandans crossed the lake to collect. Scattercorn explained to Alfred Bowers that whenever they did so, Maniga and his people “ordered” the visitors to consume such huge quantities of “food, water, tobacco, and women” that many died. The trips took a considerable toll until Lone Man intervened, tricking Maniga by crossing the lake himself accompanied by several men with bottomless appetites. Maniga grew angry at the deception and promised to visit the Mandans in the form of a flood.47

Figure 5.10. Eagle Nose Butte (also called Bird Bill Butte) viewed from the north along North Dakota Highway 1806. This was one of the sites where Lone Man initiated Mandans into the use of the sacred shrine and the Okipa ceremony. It also became a favored location for splinter groups and earned the name Village of Those Who Quarrel.

To save themselves, the people split up. The Awigaxa Mandans went west to the mountains. Others stopped beside the Missouri at Eagle Nose Butte, constructing a village on ground so high that they hoped the waters could not reach it. Some say it was Good Furred Robe—the hero who had led the Mandans out of the earth years before—who built this settlement.48

When the flood came, the people cried out to Lone Man for help. He built a plank corral around the town to hold back the deluge. A band of supple willow branches bound the structure together, much as a hoop binds the staves of a barrel. The water crested at the height of the willows, and the town was saved.49

Later, the flat-timbered barricade that had miraculously resisted the waters was re-created as a sacred shrine in the ceremonial plaza of every Mandan village. The ring of planks represented the corral, and the cedar post inside it stood for Lone Man himself. When he gave these things to the villagers, he told them, “This cedar and corral is my protector. From this time on, you will always have it.”50

The price of security was responsibility. The shrine required the annual performance of the Okipa, the long, costly, and difficult rite in which the participants endured great pain and reenacted their own history.

The Mandans deemed the trade-off worthwhile. The Okipa provided more than protection. It reinforced tribal identity. It instilled an ethos of selflessness. And it brought cohesion, self-assurance, and order to the world. One of Alfred Bowers’s informants described the overall effect: “After the Okipa ceremony was given, the people were very lucky … No bad luck came to them until the smallpox was brought by the white men.”51

The remains of the village atop Eagle Nose Bluff still survive. After its founders left, the location provided refuge for splinter groups when disputes arose and became known as the “Village of Those Who Quarrel.”52

DOG DEN BUTTE

The distinctive glacial hillock called Dog Den Butte is another place filled with meaning from the Mandan past. It sits high above the flatlands, jutting out from the Missouri Coteau about seventy miles north of the heart of the world. It has served as a traveler’s landmark for centuries if not millennia.

The hill got its name after a woman had intercourse with a dog and gave birth to nine little boy pups. After a storm separated them, the youngest boy led her to their den. The hill has borne the name Dog Den ever since. Like many of the buttes in Mandan country, it was home to an array of spiritual beings.53

Among those who made their homes at Dog Den Butte was Speckled Eagle. At one time, Speckled Eagle was the recipient of many gifts from the Mandans. But Lone Man became jealous. In particular, he wanted a fine white buffalo robe in Speckled Eagle’s possession. So he conspired with Thunder to have a tornado sweep up the robe and carry it to his people. When the Mandans found it, they gave it to Lone Man.54

Speckled Eagle was angry at the loss of his robe. So he put on the very first Buffalo Dance at Dog Den Butte, calling all the animals to participate, and as a consequence the Mandans starved. “There was hardly any game to be found,” said Scattercorn, who told Alfred Bowers the story. Even Lone Man had no luck in the hunt, but he did see some animals heading north; he followed them and found all the creatures gathered at Speckled Eagle’s Buffalo Dance at Dog Den Butte. He turned himself into a rabbit in order to watch the proceedings. Then, hoping to trick Speckled Eagle into releasing the animals, he returned to the Mandan village and had the people put on their own Buffalo Dance there.55

The ceremony was like the one at Dog Den Butte. Drummers started out beating a rolled-up hide, but Lone Man needed drums loud enough to beckon Speckled Eagle from afar. Lone Man approached four turtles about serving as drums. “The world is supported on our backs,” they said, “so we four turtles cannot leave here.” They told him to “look us over” and make “drums like us but of the strongest and thickest buffalo-bull hide.” Lone Man did this, although one of the four turtle drums fled, slipping into the Missouri below the Heart River confluence.56

When Speckled Eagle heard the turtle drums, he wanted to know what was going on, so he went to the village to see. Although the people were starving, they had gathered enough food to make corn balls for their guest, giving the impression that all was fine and that everyone was having a good time. Speckled Eagle saw the corn balls, and then he saw the boy who was playing his part in Lone Man’s Buffalo Dance.57

“What right have you to be in my place?” Speckled Eagle asked.

“I am your son,” the boy said.58

With that, the young impostor opened his eyes, and two carefully implanted fireflies flew out, mimicking the lightning that flew from Speckled Eagle’s own eyes.

The ruse worked. Speckled Eagle believed the boy was his son. He released all the animals from Dog Den Butte so the Mandans could eat. “Lone Man and I will work together,” he said, although Lone Man remained the more powerful figure.59

For centuries thereafter, the bison-hide-covered turtle drums, carved from wood and adorned with feathers, made their home among the Ruptare Mandans at Double Ditch.60

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, JULY—“MOON OF THE RIPE CHERRIES”—183261

Dogs barked and howled. Shouts pierced the dawn. In the little post beside Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, the trader James Kipp leaped from his breakfast table at the sound. “Now we have it!” he cried. “The grand ceremony has commenced!”62

At breakfast with Kipp was the artist George Catlin, who grabbed his sketchbook and raced to the Indians’ ceremonial lodge as bedlam erupted around him. The shouts and cries continued. The Black Mouths strung their bows and applied their face paint. Young men corralled their horses. Women and children climbed to the rooftops and peered westward across the prairie.63

At a mile’s distance, a solitary figure appeared, an elderly, white-clay-painted man wearing a white wolf-skin robe and carrying a pipe in his left hand. He walked straight toward the Mandan town. The man’s step was “dignified,” Catlin said. His course never veered.64

The stranger stopped outside the town walls, where the chiefs and warriors of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch met him in full battle array. The men called out to him: Where had he come from? What did he come for?

He came from the mountains in the west, was the reply. And his purpose was to open “the Medicine Lodge of the Mandans” and to prevent the “certain destruction” that otherwise faced the entire tribe.65

The cries of the women and children ceased as he entered the village.

Lone Man was here. The Okipa would begin.

George Catlin was hardly the first non-Indian to witness the Okipa, but he was the first to render a written description of the event. In fact, the painter-ethnographer left us multiple accounts of the ceremony—all similar, though varying in length and detail. His 1867 O-kee-pa came with a detached “Folium Reservatum,” to be removed at the discretion of the purchaser, describing the ceremony’s sexual content. Still more sexual details appeared in his 1865 pamphlet Account of an Annual Ceremony Practised by the Mandan Tribe. Catlin denied authorship of this work even though he is the only person who could have written it; its language is similar to that in his other reports, and scholars today universally recognize him as the writer.66

Five additional sources for our understanding of this protracted and demanding ritual are also useful. The first comes from the hand of Prince Maximilian, written during his 1833–34 stay with the Mandans. Maximilian did not see the Okipa himself but used Mandan informants to assemble his portrayal. Two other sources are brief: one by the fur trader Henry Boller, who saw the Okipa at Like-a-Fishhook Village in 1858, and the other by Lieutenant Henry Maynadier of the U.S. Army, who saw it at the same location two years later. The fourth source is the account the photographer Edward Curtis published in 1909; Curtis drew on earlier reports as well as his own interviews with Mandans on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. The final and most helpful source is the careful exposition Alfred Bowers assembled using Mandan informants in the 1930s. Not surprisingly, this account offers the most astute interpretation by far.67

In the narrative that follows, I have relied on Catlin for descriptive detail about the Okipa of 1832. But I have used the other depictions—that of Bowers in particular—to remedy misinterpretations and errors that crept into Catlin’s accounts, most of which he wrote many years after witnessing the ceremony.68 Readers should remember that the Okipa, embodying the people and their past, was intended to change.

The Okipa took place at least once each summer. Its purpose was threefold: to ensure the well-being of the tribe; to reenact Mandan history, reminding villagers of the events that bound them together; and to teach the virtue of self-sacrifice for the good of everyone.69

“It took a great deal of courage to become an Okipa Maker,” writes Alfred Bowers. In present-day parlance, the Okipa Maker was the man who “sponsored” or “gave” the event, which was truly a gift to his people. The position was not open to just anyone. It had many prerequisites: A man had to dream of buffaloes singing the Okipa songs; he had to seek the approval of the Okipa Religious Society; he had to assemble “at least one hundred articles consisting of robes, elkskin dresses, dress goods, shirts with porcupine work, knives, and men’s leggings” to bestow on participants; and he had to provide food for the feasts. So vast were these requirements that an Okipa Maker could not fulfill them on his own; he solicited help from his wives, his mothers and sisters, his clan, and even his father’s clan.70

The preparations took a year. And while giving the ceremony required considerable wealth of a man, it might also impoverish him. The entire process embodied the virtue of self-sacrifice for the sake of others. Any man who gave the Okipa earned respect for life; a man who gave it twice was a special man indeed.71

After Lone Man walked into the village, he entered the flat-fronted ceremonial lodge alone. Eventually, he returned to the door and called upon four men to prepare the space inside for the Okipa to come. The men swept the lodge and adorned its floor and walls with herbs and willow boughs while Lone Man toured the town, reciting the story of the flood and calling on residents to donate sharp-edged tools and other items to sacrifice to the water on the last day of the ceremony.72

By evening, the great lodge was ready. Lone Man retired to its confines, and the villagers waited for dawn.73

MIH-TUTTA-HANG-KUSCH, JULY 1832, OKIPA DAYS ONE TO FOUR

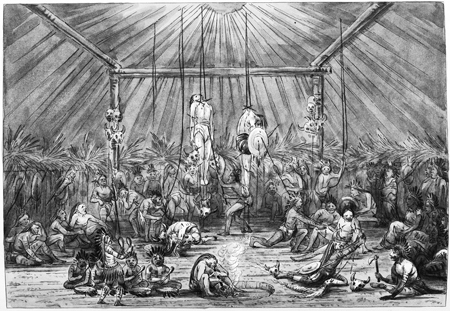

Lone Man stood in front of the Okipa lodge at sunrise, calling out for the boys and young men who intended to participate in the trials that would soon unfold inside. About fifty assembled, bedecked in paint and carrying weapons and medicine bags. The whole village bore witness as these volunteers, aspirants to the xo′pini that accrued with self-sacrifice, filed into the medicine lodge. No women could enter.74

Lone Man then turned to the Okipa Maker and gave him his pipe. He turned next to Speckled Eagle—an ancient, mythic figure in his own right—and charged him with overseeing the events to come. The lodge from which he presided represented Dog Den Butte.75

The young men began their ordeal. They presented themselves one at a time to an old man who prepared them by pulling the foreskin over the glans and tying it tight with deer sinew. Binding complete, he covered each man’s genitals with a generous handful of clay.76 In this condition, they fasted for three days or more before the real suffering began. Not a drop of water crossed their lips.

Outside, villagers gathered on rooftops around the plaza to watch another spectacle unfold. It began with the Okipa Maker leaving the lodge with Lone Man’s pipe in his hands, followed by two men carrying rattles and six men carrying a rolled bison hide. (It stood in for the turtle drums that Lone Man would bring after sunset.) They all walked to the shrine at the center of the plaza. There the musicians seated themselves and the Okipa Maker leaned his forehead against the shrine, crying out for Lone Man, asking him—according to Bowers’s informants—to “send the people all they asked for, to bring the buffaloes near the villages, and to keep all bad luck away.”77

The music then began, the drummers singing and beating the rolled-up hide. On cue, the fasters emerged from the ceremonial lodge. They wore buffalo robes and imitated those animals as they danced. Four times they danced, and four times they retreated to the lodge, while the musicians played and the Okipa Maker kept up his prayers.78

That evening, Lone Man replaced the rolled bison hide with the sacred turtle drums. Anticipation mounted as the drums reverberated into the night.79

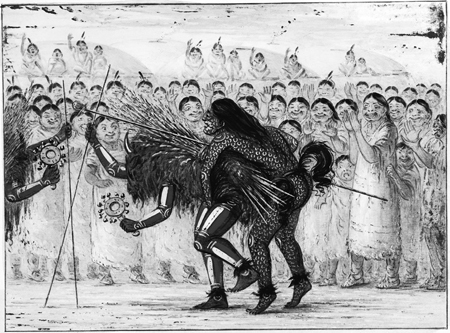

Day two marked the appearance of the eight Buffalo Bulls—men wearing body paint, bison robes, and bison-robe headdresses. A single bison horn extending from the back of each costume had bunches of willow attached, reminding the villagers of the flood and of Lone Man’s intervention on behalf of their ancestors. The Buffalo Bulls circled up in the plaza and then separated in pairs to the cardinal compass points. They held their upper bodies horizontal as they danced, shuffling and roaring like the animals they represented, a performance that lasted about a quarter of an hour. When it ended, the entire town erupted in “a deafening shout of approbation” as the Okipa Maker, the dancers, and the musicians returned to the Okipa lodge.80 Again and again the Okipa Maker emerged and prayed; again and again the bulls danced—eight times in all. Each hour and each dance brought more energy, more excitement.

Figure 5.11. Ready for Okípe Buffalo Dance—Mandan, photograph by Edward S. Curtis. A single bison horn bearing willow branches adorned the back of each dancer.

Day three was the climax. The Mandans called it “Everything Comes Back Day.” It re-created Speckled Eagle’s release of the animals from Dog Den Butte. For ceremonial purposes, the square-fronted Okipa lodge was Dog Den Butte, and when Speckled Eagle liberated the creatures inside, a horde of grizzly bears, swans, beavers, wolves, vultures, rattlesnakes, bald eagles, and antelopes swarmed over the plaza. Each of the costumed dancers “closely imitated the habits of the animals they represented,” Catlin said. The ever-hungry grizzly bears hunted for food and devoured the young antelopes. When female spectators tried to appease the grizzlies with plates of meat, the bald eagles stole it and fled to the plains. There were not eight but twelve buffalo dances on this day. At the end of each one, the animals “all set up the howl and growl peculiar to their species, in a deafening chorus … the beavers clapping with their tails, the rattlesnakes shaking their rattles, the bears striking with their paws, the wolves howling, and the buffaloes rolling in the sand or rearing upon their hind feet.”81

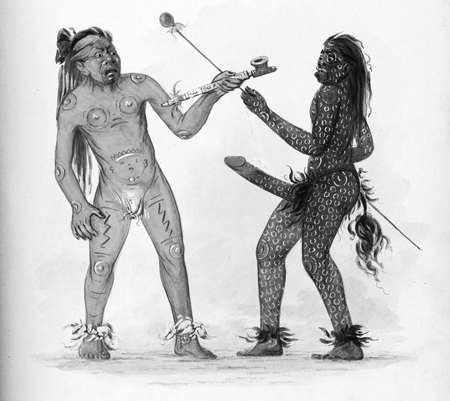

Then, amid the dancing and din, a “scream burst forth from the tops of the lodges.” All eyes turned to the western prairie. There, once again, a solitary figure approached the village. But this was not Lone Man with his wolf skin, white paint, and steady pace. This figure ran frenetically, zigzagging toward the town at top speed. Black paint with white adornments covered his skin. He carried a long, slender wand in one hand. A huge “artificial penis” hung below his knees. It too was painted black, except for the “glaring red” glans, “some four or five inches” in size.82

When he entered the town, the women fell into a tizzy.

The newcomer’s name was the Foolish One. He pranced toward clusters of women in the crowd, raising his wand to pull his penis erect. The women “hastily retreated in the greatest alarm,” Catlin said, “tumbling over each other and screaming for help.” The fracas drew the attention of the Okipa Maker, who now approached the Foolish One and thrust Lone Man’s protective pipe in his face. The “charm of the pipe” held him spellbound “until the women and children had withdrawn from his reach.” The scene was “amusing beyond description,” Catlin said, and the assembly roared with laughter.83

With the women temporarily safe, the Okipa Maker drew back the mystical smoking implement. Again the Foolish One raised his wand, again his penis rose, and again he capered about to a chorus of female screams. Each time, the sacred pipe came to the rescue. The Foolish One elicited fear as well as mirth. He brought real misfortune, and the fate of the people hinged on the preternatural power of Lone Man’s pipe.84

After several episodes of this, the Foolish One turned to the buffalo dancers and, to the onlookers’ delight, mounted one of them, slipping his penis beneath the bison robe and “perfectly” imitating “the motions and noise of the buffalo bull on such occasions.” He did this with four of them before succumbing to exhaustion.85

Figure 5.12. A Test of Magic, sketch and watercolor by George Catlin based on his drawings of the July 1832 Okipa at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. The Okipa Maker confronts the Foolish One with Lone Man’s pipe on day four of the ceremony.

The women sensed their opportunity. They circled close about the Foolish One, tempting and teasing him with “lascivious attitudes.” He did not respond. One woman seized his wand and snapped it over her knee. With this, he made a dash for it, racing for the prairie with the women in pursuit. Soon they made a gleeful return, led by the young woman who had disarmed the miscreant. In her arms, she carried his penis “as she would a child, wrapped in a quantity of sage, the glans rising above all.” At the door of the Okipa lodge, she stopped, hoisted high by four companions.86 For the thirsty and enervated young men completing their third day in the lodge, the real trial was about to begin.

Day four was “the hunting day.” Physical suffering was its hallmark. In some instances, rites of personal sacrifice began on the second or third day, but they still climaxed on day four. Their meaning is easily misconstrued. Perseverance through pain was neither a rite of passage nor an emblem of manhood. It was an offering, a praise song, a homage to the Mandan spirits. “As Mandans,” Cedric Red Feather explains, “we are taught that there are only two things that we can give to the spirits, the only two things that we truly own: our flesh and our time. During the Okipa we give to the spirits both of these.”87

The volunteers, who had fasted since the beginning, presented themselves in their weakened state to have pairs of incisions cut into the skin and flesh of their chests, backs, and limbs. Assistants ran wooden splints through each pair and attached leather thongs to each splint. The two chest thongs extended upward and attached either to beams or to the earth-lodge smoke hole. Now, pulling on the thongs, more assistants lifted the supplicants into the air, suspending them by the flesh of their chests. The other thongs, hanging downward, were tied to bison skulls and other weighty objects to add pain. As the young men raised their voices in prayer, attendants on the ground twirled them around and around until consciousness faded; only then were they lowered.88

When awareness returned, each participant crawled to yet another station in the Okipa lodge, dragging the bison skulls behind him. Here, he laid the little finger of his left hand on top of a skull, and a man with a hatchet struck it off with a single blow. The men then stumbled outside.89

Meanwhile, the Buffalo Bulls danced and danced, emerging time and again from the lodge into the plaza. They danced sixteen times on this last day. At the end of their final performance, they turned to confront a band of hunters bearing weapons. Repeatedly, they charged the hunters, who stabbed them in the legs with their spears. With blood flowing from real wounds, the buffaloes dropped to the ground as if dead.90

Figure 5.13. The Foolish One mounts a buffalo dancer as onlookers express delight, sketch and watercolor by George Catlin based on his drawings of the July 1832 Okipa at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch.

Figure 5.14. The triumphant women return, led by the young woman who has disarmed the Foolish One, another sketch and watercolor by George Catlin based on his drawings of the July 1832 Okipa at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. She will also lead the young married women in Walking with the Buffaloes in the evening.

Figure 5.15. Young men suspended by the flesh of their chests in the Okipa ceremony, with bison skulls hanging from their limbs, a drawing by George Catlin of the July 1832 Okipa at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch.

The participants—weak and bleeding from their trials in the lodge—now spaced themselves in a circle around Lone Man’s shrine. Still dragging their bison skulls, they began to run. The aim was to run without fainting until the skulls tore away from the flesh. But most lasted only half a lap before collapsing, whereupon helpers seized them by the wrists and dragged them around the plaza until, one at a time, the thongs tied to the bison skulls ripped out of their skin. They had given their flesh and their love to the spirit world, and now they were left to restore themselves without earthly assistance.91

When the young men were all finished, the entire village walked to the river, where they cast the edged tools Lone Man had collected four days earlier into the water. The Okipa Maker proclaimed the Okipa over.92

But one more transaction remained.

Lone Man’s pipe had thwarted the Foolish One’s wanton sexuality the day before. And the men of the Buffalo Bull Society had helped the Okipa Maker get ready over the previous year. Now it remained for the young married women to repair the distribution of xo′pini in the village. As darkness fell and the townspeople returned to their earth lodges, select individuals gathered to perform one last rite, in which young married women had intercourse with the old men—the Buffalo Bulls.

The Mandans called it Walking with the Buffaloes.* It drew the herds near, they believed, but it also did something else: Through intercourse, the old bulls transferred xo′pini to their youthful female partners. They in turn passed it on to their husbands, whose risk-filled lives were constantly draining their supernatural powers.93

Not all the ceremonial buffalo bulls were old men. The Mandans treated important strangers, well endowed with xo′pini, as buffaloes as well. Catlin reported that the women invited not just the old men and chiefs but also “the fur trader of the post [James Kipp], my two hired men, and myself, to partake.”94

This rite, like the others, was exhausting: The women danced, selected partners, disappeared into the night to complete the act, then returned and started dancing again. “Some of them,” Catlin believed, took “a dozen such excursions in the course of the evening.” When the night was over, all were spent. “This most extraordinary scene gradually closed by the men returning from the prairies to their homes.”95

MISSOURI HIGHWAY 79, NOVEMBER 1, 2008

The sun is setting as I drive south toward St. Louis on Missouri Highway 79. The radio buzzes with preelection patter: Bush-Obama, Obama-Bush. On and on, more and more.

I turn off the soundbox and wrap my mind around the day’s events. My Mandan friend Cedric Red Feather gave me a new name today. Henceforth, I am Good Robe Woman. I think about each word: Good. Robe. Woman. All my life I’ve had one name, with a few nickname variants. Now, however, I have a name with meaning. The feeling is different. The words convey identity and responsibility. Can I—do I—live up to their spirit? I feel honored. I feel nervous.

I do not have a religious bone in my body. Gods and spirits do not inhabit my world. But I respect their place in the worlds of others. Most of my friends, I suspect, believe in some sort of god. Some see spirits in the earth, the animals, the rocks, and the trees. Some are born again. Some feel spiritual forces all day, every day. My world, however, is one in which rocks are rocks, trees are trees, and birds are birds. It may fill me with wonder, love, joy, or heartache, but in the end, it is what it is.

Where does this leave me with Cedric, who also initiated me into the Mandan White Buffalo Cow Society on this day? The conundrum seems to bother me much more than him. I’ve told him about my spiritual disbelief. His response is simple and consistent: “You have a good heart.”

I hope he is right. But whatever is in my heart, how can I understand the Mandans I am writing about when they inhabited a world so different from my own? Every historian faces this problem. We hardly talk about it, but it is at the crux of our work. Can I even begin to describe the Mandan universe? As the western light fades, I realize that my new name is a gesture of trust.

My confidence and my humility seem to grow hand in hand.