SIX

Upheavals: Eighteenth-Century Transformations

MANDAN VILLAGES, CA. 1750

In the years following La Vérendrye’s visit, the Mandan world was transformed. Horses enlivened travel across the plains. Warfare took on new characteristics. Commerce flourished, and more strangers appeared. By the mid-eighteenth century, the horse frontier and the gun frontier converged on the upper Missouri, making the Mandan and Hidatsa towns one of the most dynamic centers of interaction in North America.1

Few documents survive that tell us of this tumult. Historians must mostly rely on the same kinds of sources that shed light, however dim, on the Mandans’ earlier years—archaeological remains, tangential accounts, after-the-fact descriptions, and oral traditions transmitted across generations. La Vérendrye’s 1738–39 report is like a flash of illumination in a poorly lit archival reading room. When the lights fade, we find our way by whatever means we can.

HORSES

Horses had lived and evolved in North America for millions of years before disappearing from the continent some ten thousand years ago.2 Christopher Columbus and other Spaniards reintroduced them beginning in 1493. Thereafter, mustangs migrated north from Mexico along with Spanish colonists and conquerors. Even though their access to the animals was limited, Native Americans proved adept horsehandlers, and by the mid-seventeenth century, Apaches, Utes, and Navajos in the Southwest managed to acquire some mounts. Then, in 1680, New Mexico’s Pueblo Indians launched a revolt that liberated both people and livestock from the Iberian colonizers, placing large numbers of horses in native hands.3 It was only a matter of time before they seemed to be everywhere. Horses flourished on the North American steppe, and by 1750 could be found as far north as modern-day Alberta and Saskatchewan. But at higher latitudes, the cold climate made their care and maintenance impractical if not impossible.4

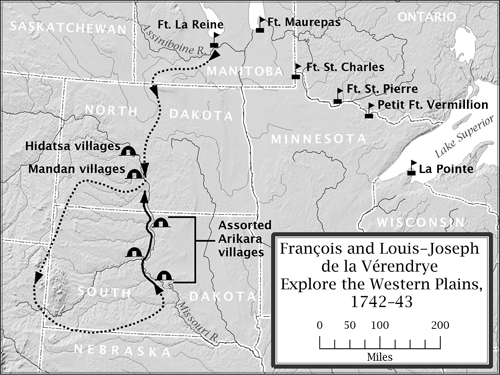

Map 6.1

There is no known description of the Mandans’ first glimpse of a horse. But accounts from other peoples are suggestive. Aztec couriers had described mounted Spanish conquistadors to the emperor Motecuhzoma in 1519: “Their deer carry them on their backs wherever they wish to go,” the messengers said; the animals were “as tall as the roof of a house.” The Piegan Blackfeet, who lived on the plains north and west of the Mandans, saw their first horse in the 1730s—possibly as early as the autumn of 1730—when unnamed enemies shot an arrow into the belly of a Shoshone Indian’s mount. “Numbers of us went to see him,” recalled an eyewitness named Saukamappee, “and we all admired him.” The dead pony, he said, “put us in mind of a Stag that had lost his horns.” The Piegans called the animal “the Big Dog,” since “he was a slave to Man, like the Dog.”5

Pierre de la Vérendrye makes it clear that by 1738–39, when he first visited them, the Mantannes already knew about horses. They had seen the animals among the Arikaras and Pawnees, and they had probably seen them among trading peoples too.* But the Mantannes still had no mounts of their own.

In September 1739, nine months after La Vérendrye had decamped, the two men he had left behind to learn the local language made their way back up north to Fort La Reine. They brought with them both news and linguistic acumen. In early June, they said, a host of western Indians—perhaps two thousand people from “several” different tribes—had arrived at the “great” Mantanne “fort” on the west bank of the Missouri River. They evidently came to trade “every year,” selling bison skins and receiving Mantanne “grain and beans” in return.6

Figure 6.1. A Mandan saddle made of hide, wood, sinew, and metal.

The visitors also had horses. Indeed, their visit, their commerce, and their stories well expressed the new, horse-borne mobility that was transforming the plains. One of the headmen showed off a Spanish bridle—almost certainly from New Mexico—with “the bit and the curb … of one piece.” He talked at length about Spaniards who wore cotton clothes, “played the harpsichord,” and “prayed to the great Master of Life in books” that appeared to be “made of leaves of Indian corn.”7

The Mantannes soon got mounts of their own. La Vérendrye’s son Pierre took another trip to the villages two years later, hoping to make his way to the Western Sea. But when he reached the Mantannes, he decided to go no farther “for lack of a guide.” Pierre returned to Fort La Reine in the fall of 1741 with “two horses,” an embroidered cotton “coverlet,” and “some porcelain mugs”—all evidence of the far-flung trade connections that converged on the upper Missouri. Pierre may have bought the horses from the villagers or from mounted visitors—it hardly matters. If he could get horses, the Mandans could too.8

PIERRE, SOUTH DAKOTA, FEBRUARY 16, 1913

Even children at play can unearth bits of plains history.

The time was four thirty in the afternoon. Hattie May Foster, Ethel Parrish, Martha Burns, and Hattie’s sister Blanche had just climbed a prominent knob on the west bank of the Missouri River. The hilltop offered a prospect of the country in all directions, but the town of Pierre, South Dakota, on the far side of the river, was the most consistently appealing view.

A year earlier, local boys had built an earthen redoubt atop this knob, heaping dirt into a two-foot wall and trampling the ground again and again in mock battles and war games. Now three of them, distracted from a hunting outing by the female presence, scaled the hill to join the girls. They all stood talking. Hattie described what happened next:

“I was scraping in the dirt with my foot,” she said, when “I saw the end of the plate showing about one inch above the ground.” She kicked it out and picked it up. “It looked like a lining out of a big range stove.” The teenagers gathered around and wondered.

“What is it?” Hattie asked.

“It is a piece of lead,” George O’Reilly replied. There was some sort of writing on it. George took out his knife.

“Hand it here and I’ll scrape the dirt off so we can read what is on it.”

Hattie gave him the plaque, and he scraped at it to reveal the number “1743.”

“It is the stone Moses wrote the Ten Commandments on,” gasped Martha Burns. The others were less sanguine.

“It isn’t anything but a piece of lead,” George said. “I will take it to the hardware store and sell it for about five cents.”

The time was late, and George had to go milk the family cow. He tucked the plate under his arm and headed home. On the way, he ran into an older boy who looked at the plaque and said it was valuable. Hattie May Foster never got it back.

“The next day I asked George for the plate, and he said he took it home and was going to have it,” she said.9

What Hattie had unearthed was a plaque buried 170 years earlier by two sons of Pierre de la Vérendrye, sent by their father to go beyond the Mandan villages and find the Western Sea.

NORTHERN PLAINS, 1742–43

The expedition undertaken by La Vérendrye’s third and fourth sons, François and Louis-Joseph, was not a large one. It consisted of just the two brothers, two villagers, and two hired hands, possibly the men who had lingered among the Mantannes in 1738–39 to learn their language. The sole written account comes from François, who, like his father on the previous expedition, put his notes into a letter, composed after the fact for French officials. What has come down to us is at best a copy of his original, and the content is frustrating for any modern reader.10 Rife with vagary and ambiguity, it conveys little direct information about the Mandans in 1742–43. But it nevertheless gives us a glimpse, as the archival lights fade, of life on the northern plains at that time.

“We left Fort La Reine on April 29 [1742] and arrived among the Mantanes on May 19,” wrote François. “We remained there until July 23.” We don’t know what passed in this two-month period, except that they were waiting for the Gens des Chevaux, or “Horse People”—probably the mounted tribe or tribes that La Vérendrye’s hired men had seen trading with the villagers three years earlier. The plan was to travel west with these Indians and somehow make it to the Western Sea. When the Horse People did not appear, the brothers found two Mantanne men willing to guide them beyond the Missouri River to where they might find the elusive nomads.11

Across the plains they went. If they had a compass, François does not mention it. Their astrolabe was “useless,” its “ring being broken.” Thus we learn only generalities: The men “traveled twenty days west-southwest,” then “south-southwest,” “southwest,” “south-southwest, sometimes northwest,” and lastly “east-southeast” before heading back toward the Mandans and Fort La Reine.12

The landscape François described offers a few clues. The region marked by “earths of different colors, such as blue, a kind of vermilion, grass green, glossy black, chalk white, and others the color of ocher” could only have been the western Dakota badlands, encountered early in their trip.13 But aside from the Missouri River itself, the terrain of mountains, streams, and prairies is hard to identify.

François reported that he buried the lead tablet “on an eminence” near the Missouri River on March 30, 1743. The location remained unknown for 170 years until Hattie May Foster idly scuffed in the dirt. Her discovery put a new pin in the map. In the years since then, historians have reached a flexible consensus that the brothers’ likely route was a loop that first trended southwest to either the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming or the Black Hills of South Dakota, then turned east to the plaque buried beside the Missouri, and thence northward along the river to the Mandans.14

François de la Vérendrye’s description of the people he encountered is as frustrating as his account of geography, with only obscure names and few ethnographic details. But it does nevertheless reveal a world astir with human movement as plains peoples reinvented themselves on horseback. The four Frenchmen traveled with the two Mantannes until September, when they joined a village of Beaux Hommes, or “Handsome People.” After three weeks, Beaux Hommes guides took them to a town of Little Foxes. The inhabitants, learning that the explorers sought the Gens des Chevaux, hastened them to “a very large” Gens des Chevaux village just two days away. These in turn led the party to a band of Pioya (possibly Kiowa) Indians with whom the La Vérendryes traveled for four more days until they encountered yet another group of Horse People, who were, wrote François, “in great distress. There was nothing but weeping and howling,” for the Gens du Serpent—Shoshone Indians—had attacked and destroyed “all their villages” and only a handful had escaped. The survivors nevertheless agreed to escort the Frenchmen to the Gens de l’Arc, or “Bow People.”15

Map 6.2

Figure 6.2. Badlands in western North Dakota.

By the time they found the Bow People, another month had passed. The voyageurs—long accustomed to canoe travel in the north woods—were now on horseback themselves. François did not say when or where they got mounts. “All the nations of these regions have a great many horses, asses, and mules,” he observed, “which they use to carry their baggage and for riding, both in hunting and in traveling.”16 The very name Horse People suggests how quickly and thoroughly some nations had incorporated the animals into their lives.

The brothers traveled with the Bow People for several winter months, their band growing as “various villages of different nations” joined them. Soon, “the number of warriors” alone “exceeded two thousand.” The grand total may have been eight thousand or more. The sight of so many travelers must have been spectacular. A century later, George Catlin found “few scenes” more impressive “than these cavalcades, sometimes ten or fifteen hundred families, with all their household and live stock in motion, forming a train of some miles in length over the green and gracefully swelling prairies.”17

Eventually, wanting to return to Fort La Reine, the La Vérendryes parted ways with the Bow People and turned east, arriving among the Arikaras in March 1743. On the banks of the Missouri, not far from the hilltop that soon bore the plaque, they met a Spanish-speaking Arikara man who still recalled his baptism and Christian prayers. He described a “great trade” that his nation carried on with the Spaniards of New Mexico.18

The brothers headed north with Arikara guides, passing a group of Gens de Flêche Collée—possibly Cheyennes or Yanktonai Sioux—before reaching the Mantannes on May 18. By early July, they were back at Fort La Reine, escorted home by a large band of mounted Assiniboines. Just four years earlier, when Pierre de la Vérendrye had made his own trek, the Assiniboines had all traveled on foot.19

THE MANDANS AND THEIR HORSES

The Mandans never became full-fledged, nomadic equestrians like the Gens des Chevaux or other plains peoples such as the Comanches and Lakotas. But the villagers did welcome horses and incorporate them into many aspects of their lives.

Boys learned to ride by the time they were eight or nine, girls by age ten. Boys tended the herds, broke colts, and trained them. They also learned roping and trick riding for warfare. In their teen years, boys spent most of their summer days with the herds. They might swim, ride, play, pray, or hunt small game along the way, but their main charge was the horses. In winter, men sometimes joined the boys to water the animals and shuttle them to and fro among hard-to-find grazing areas where thick grass lay beneath the snow.20

Winter also brought Mandan ponies directly into the feminine realm of the earth lodge. Here, when weather or enemies threatened, a family’s horses took shelter in a little corral built just inside the entryway. “On the right hand side of the door, were separate Stalls for Horses,” observed the Canadian geographer-explorer David Thompson. If the herd was large, the villagers brought only the best horses inside and left the rest on the prairie or secured beneath the scaffold-like drying stages outside their earth lodges.21

Winter feeding of this stock fell in large part to Mandan women. They took their hoes out to the plains, cleared snow, and collected hay, tying it into bales that the ponies themselves carried home. Women also felled cottonwoods and gathered cottonwood bark, branches, and saplings to augment the hay. In 1805, Meriwether Lewis was “astonished” to find that cottonwood was “the principall article of food” for Mandan horses in winter.22 Wood was never abundant in Mandan country, and the use of cottonwood as fodder took a toll on new growth and the renewal of riverine trees.

Horses constituted a new kind of wealth for Indian peoples everywhere. On the southern plains, most famously, individuals and entire bands of Comanches accrued astonishing fortunes in livestock. The result was a political economy in which a few of the “superrich”—to use the historian Pekka Hämäläinen’s term—wielded immense power and prestige. Similar dynamics unfolded among the Blackfeet, on the plains northwest of the Mandans.23

Horses also added to Mandan wealth, as individuals and villages accumulated mounts, and some surely became richer than others. A nineteenth-century tally, which may jibe with eighteenth-century numbers, showed that the Mandans averaged 2.9 horses per lodge. So Mandan herds remained small, and for good reasons. The climate on the northern plains was less conducive to equine survival than that farther south. (Hämäläinen calls the Missouri River “the ecological fault line of Plains Indian equestrianism.”)24 Moreover, having lots of horses would have required the villagers to abandon their sedentary, agricultural ways and embark on the nomads’ endless quest for pasture. Farmers-turned-herders such as the Cheyennes deemed it worth their while to do so. But for the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras, a settled life of gardening and opportunistic hunting seemed the better choice. The decision no doubt expressed their attachment to food security and to social and cultural traditions that were unsustainable on the hoof.25

Regardless, the small size of Mandan horse herds was a misleading indicator of the amount of equine traffic and activity in the villages. Herd size fluctuated, and though not many animals accumulated, the villagers brokered many, many ponies through their towns. Crows, Kiowas, Arapahos, and Cheyennes from the south and west sold the Mandans horses, which they in turn traded to Assiniboine, Cree, Lakota, and European visitors from the north and east. This was a logical outcome of time-honored trading patterns, and it magnified the Mandans’ commercial prominence.26

DOUBLE DITCH IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

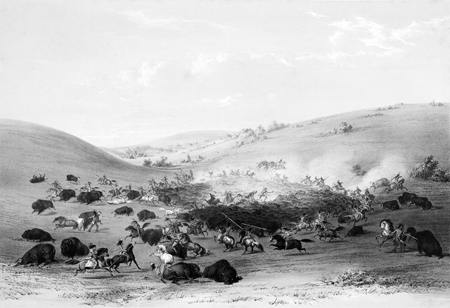

The adoption of horses did alter the Mandan bison hunt. Scouts seeking herds now ranged farther from their villages. So too did hunters and their supporting helpers. The villagers still used their old-fashioned bison drives, but mounted men also learned to surround the animals, then chase and kill them on horseback.27 The women who processed and transported the carcasses used ponies too. Even though hunt camps could now be farther from home, getting the meat back was easier: A horse hauled five times as much weight as a dog and three to four times as much as a woman.28 Still, there were new dangers: Distant excursions meant that hunting parties as well as the people left behind were more vulnerable to enemy attack.29

Figure 6.3. A mounted bison surround, hand-colored lithograph by George Catlin, published in 1844. This was a preferred hunting method for plains peoples after their adoption of horses. Mounted hunters continued to choose bows and arrows and lances over firearms, which were hard to manage on horseback.

Perhaps for this reason, the horse did not bring a universal surge in bison hunting to the Mandan settlements. Villages stuck to their own subsistence practices, which in any case differed from town to town. Residents of On-a-Slant, for example, ate lots of fish, while the people of Double Ditch ate few. But these patterns changed over time. At Double Ditch, archaeologists found that during the town’s first two centuries, until about 1700, the inhabitants left plentiful bison remnants behind. Then, as the equestrian era got under way, the quantity of bison bones diminished and bird bones became more common. The same was true at Larson, the east-side settlement a short distance upstream.30

It is impossible to say for sure why this happened. Bison populations may have declined as horseback hunting increased. Herds may have altered their migration routes. Or the east-side townspeople may have decided to trade for their bison rather than hunt for them. Yet one explanation stands out. As Spanish mustangs proliferated in the eighteenth century, the Mandans faced growing danger from mounted enemies. Larson and Double Ditch, on the east bank of the Missouri, were especially vulnerable to the forays of Lakota newcomers pushing toward, and eventually across, the river. Instead of venturing long distances on risky bison hunts, the villagers may have sought safety and sustenance close to home.31

THE UPPER MISSOURI RIVER IN THE MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

As we have seen, the formidable fortifications the Mandans built around their villages suggest that enemies threatened them from the very beginning of their settlement in the Heart River area. But the equestrian age brought new violence on horseback, and clashes between villagers and Lakotas became frequent. At first, by virtue of location and commercial prominence, the villagers held the preponderance of horses.

In 1741–42, a mounted “party of enemies”—Pawnees, Arikaras, Assiniboines, Mandans, or someone else—assaulted some Sioux women digging prairie turnips. This particular incident had no long-term consequences; after knocking the women down, the assailants left “without doing them any further harm.” But subsequent encounters caused significant loss of life. Not long after, a Lakota hunting party turned back an assault by mounted enemies and killed “many” of the attackers, an outcome that highlights the martial skill of the still-horseless Sioux, who fought with spears in the encounter.32

Eventually, the Lakotas acquired enough horses to launch mounted raids and to embrace nomadic equestrianism as a way of life. They sent out a mounted war party of their own in 1757–58. Two years later, in 1760, a Hidatsa-Sioux encounter led to deaths on both sides. Anyone who looks at the longest-running Lakota winter counts cannot help noticing this escalation of conflict. The count kept by a man known as Brown Hat (Battiste Good) is indicative: In the four decades after 1700, violent clashes marked eighteen winters; the number rose to twenty-six—a 44 percent increase—in the four decades after 1740.33 Since counts were maintained by different people over time, the proliferating references to armed strife might express the predilections of different keepers. But as horses penetrated the plains and the Lakotas claimed new turf, relentless warfare was indeed the new reality.

The lightning-fast raid on horseback became a plains military staple that necessarily favored the nomadic peoples. Life in the saddle made them superior equestrians. And their dependence on the hunt—often carried out with bows and arrows at a gallop—gave them martial expertise superior to that of the Mandans. The villagers, always in the same place and amply supplied with horses, food, and goods, were easy and appealing targets. War parties could swoop down on Mandan gardeners and their horse herds, steal slaves and ponies, and be gone.

APPLE CREEK, 1771

“They burnt the Mandans out,” says a Lakota winter count for 1771. “Set fire on Mandans,” says another. So important was the event that Edward Curtis heard about it when he visited the Sioux more than a century later. “About 1770 or 1775,” he learned, the Sioux had enough men near the Missouri “to attack and almost exterminate a strongly stockaded Mandan village near the present site of Bismarck, North Dakota.”34

The village was south of Bismarck, close to a stream called Apple Creek. It may have been the town identified by the archaeologist George F. Will in 1910, below the creek’s ever-shifting mouth. By Will’s time, persistent plowing had rendered the remains barely visible, and all that could be seen were signs of a fortification ditch and a few earthworks.35

The Sioux took over the Apple Creek area after destroying the Mandan town.36 Today, suburban houses and swimming pools have replaced earth lodges and tipis along the stream’s sandy banks.

ON THE UPPER MISSOURI RIVER, NEAR THE PRESENT SOUTH DAKOTA–NORTH DAKOTA BORDER

The Lakotas were not the only people migrating west toward the Mandan villages in early modern times. Bands of Cheyennes were also on the move, forsaking eastern Minnesota in the late 1600s and building new settlements first along the Minnesota and Sheyenne rivers and then, by the mid-1700s, beside the Missouri. In the area of the modern South Dakota–North Dakota border—in between the Mandans and the Arikaras—they planted crops and lived in earth lodges like those of their villager neighbors.37

Only one of the Cheyenne settlements was fortified, which would suggest the newcomers sensed little danger from enemies. Thanks to their friendly ties to the Sioux, they probably felt more secure than the Mandans did. But relations between Cheyennes and Mandans were less sanguine. The villagers told Prince Maximilian that before 1781, “the Dacotas were not very dangerous [to them], but the Arikaras, Cheyennes, and other prairie nation[s] were always their natural and fierce enemies.”38

The Cheyenne occupation of the Missouri River valley was short-lived. By 1800, if not sooner, most bands had decamped to the southwest, becoming full-fledged equestrian nomads. “Now that the Chayennes have ceased to till the ground, they roam over the prairies west of the Missouri,” wrote the fur trader Pierre-Antoine Tabeau in 1804–1805. Scholars have attributed the itinerant shift to multiple causes, including the Cheyennes’ commercial savvy, their acquisition of large horse herds, their attraction to the bison hunt, and their vulnerability in the face of Sioux inroads.39 But the Mandans explained it differently. According to one tradition—admittedly vague in its time frame—the villagers fought a grueling, daylong battle against the Cheyennes until a Mandan headman told one of his warriors to bring him a young cottonwood from the river bottom. The chief “planted the little tree in the ground in front of and close to the enemy.” Then, as he wrapped his arms around it, the sapling changed “into a colossal trunk,” and a sudden storm heaved it skyward. When it landed, it “crushed” the Cheyennes and drove them “across the Missouri.” After 1800, the two tribes vacillated between trading and raiding.40

ARIKARA VILLAGES, 1743

Horses circulated freely, but firearms did not. The La Vérendrye brothers gained a key insight into eighteenth-century commerce and war when, at an Arikara village in 1743, a man (possibly speaking Spanish) told them that in return for “buffalo hides and slaves” the Spaniards had given them “horses and goods as the Indians desired, but no muskets or ammunition.”41

The last phrase—“no muskets or ammunition”—bears repeating. A Spanish law forbade providing weapons “offensive, or defensive, to the Indians.” If this was not clear enough, the next phrase eliminated any ambiguity: “not to any of them,” it added.42 To arm Indians was to arm the enemy. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in which Indians had risen up against the Spanish and expelled them from New Mexico for thirteen years, had shown how fiercely well-armed natives could fight.

But enforcement of the Spanish gun ban was imperfect. Spaniards as well as native, French, and British brokers circumvented the prohibition. Still, despite the smuggling, southwestern tribes found firearms scarce for much of the eighteenth century. They may have been horse rich compared with Indians elsewhere, but because of Spanish policy they were gun poor.43

How different the situation was to the north and east! French and English traders had been selling guns to Indian peoples from the earliest days of the fur trade. In Mandan country, most of the guns came from the Hudson’s Bay Company, whose ships delivered muskets directly to bayside posts deep in the northern interior. Fewer came from French traders who, having to paddle and portage their wares inland, offered fewer awkward, hard to carry heavy items.44 But practical problems aside, neither Frenchman nor Englishman had any compunction about selling firearms to Indians.

The Mandans had few if any muskets before their 1733 truce with the Assiniboines. But afterward they acquired more of them, primarily from Cree and Assiniboine brokers who brought them south from the posts of the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies. La Vérendrye noted in 1738 that the villagers purchased all the weapons they could from his Assiniboine companions.45

The gun, unlike the horse, did little to alter the buffalo chase. Long-barreled, muzzle-loading muskets were hard to aim, fire, and reload on horseback, and mounted hunters continued to prefer lances or bows and arrows—now with iron points—for their outings.* So too did mounted warriors, even into the nineteenth century. “Their main dependence either in war or the chase, is upon their bows and arrows, their lances and shields,” an American army lieutenant wrote of the Lakotas in 1844–45.46 A skilled bowman might let loose two or three arrows in the time it took to reload a traditional musket.

Yet native hunter-warriors still coveted firearms. Tribes with guns had an undeniable advantage over gunless opponents. At a distance, the new weapons were much more effective than bows and arrows. Their explosive crack put enemies to flight and boosted the courage of users. Northern plains peoples eventually became arms connoisseurs. They scorned Belgian or American knock-offs, demanding that European (and later American) traders supply them with genuine English “Northwest guns,” replete with trigger guards and handsomely engraved sideplates. The Indians also modified weapons to their liking, adorning them with strips “of red cloth” and shortening musket barrels to make them useful in the saddle.47

Firearms may have been particularly valuable to the Mandans when horse-borne raiders bore down on them. Used from within a walled village, a long-barreled muzzle-loader had few of the disadvantages it had on horseback. Reloading was easy. It might even be handled by women or other noncombatants. Stable footing made aiming and firing a cinch. The Mandans came to consider firearms “very essential articles for their defence,” wrote a fur trader, “and accordingly every individual has a stock of Ball and Powder, laid up in case of any sudden emergencies.”48

PORTAGE, WISCONSIN

Pennesha Gegare enters the historical record not along the upper Missouri but in the country surrounding the upper Great Lakes. This Frenchman apparently traveled alone or with Indian companions, and he usually left no written record. He is emblematic of the thinly documented contacts the Mandans had with Europeans in the initial years after La Vérendrye.

Gegare is most famous for a farce that he perpetrated on a Bostonian named Jonathan Carver on October 11, 1766. The men met at Portage, Wisconsin, the famous overland crossing between the Fox and Wisconsin rivers, where Gegare ran a portage-assistance operation. He detected naïveté in his New England–born customer, and the temptation was irresistible. He spun out a yarn about an Indian who taught a pet rattlesnake to come when it was called. Carver had doubts, but he fell for it.49 The story of the snake and Carver’s gullibility spread far and wide. If Gegare, usually called “Pennesha,” told Carver anything else, the tenderfoot Bostonian did not mention it.

An account from the hand of Peter Pond tells us more. Pond, a trader himself, encountered Pennesha at Portage in 1774. He had heard the story about Carver and the rattlesnake, and he enjoyed the joke as any woodsman would. But he also noted that in his younger years, when the French controlled the interior, Pennesha had served as a soldier in the Illinois country, in the string of French settlements that materialized along the banks of the Mississippi River just below the mouth of the Missouri.50

Young Pennesha had little taste for the service, Pond tells us. “He Deserted His Post & toock his Boat up the Miseeurea among the Indans and Spant Maney years among them.” He made his way upstream incrementally, “from Steap to Step,” learning Indian languages along the way, until finally “he Got among the Mondans [Mandans].” There the deserter “found Sum french traders” from Fort La Reine, who “toock Pinneshon to the facterey with them.” He worked for the Fort La Reine outfit until the conflict known as the French and Indian War expelled the French from North America and put the trade in British hands.51

It is possible that this was another tall tale to tempt a stranger, not to mention historians several centuries later. But Pond was a seasoned soldier and fur trader, and he seems to have believed it, having “Hurd it” from Pennesha’s own “Lips Meney times.” The story has the ring of truth, and the Illinois country was a likely jumping-off point for an ascent of the Missouri. By the 1730s, French soldiers were stationed at Cahokia and at a larger garrison called Fort Chartres, built farther down the east bank of the Mississippi in the previous decade. Moreover, it is perfectly plausible for the peripatetic Frenchman to have run into his countrymen in the Mandan towns. They might even have been members of one of the La Vérendrye expeditions. The La Vérendrye writings that survive do not mention such an encounter, but there is a tantalizing tip: The Arikaras told François and his brother that “a Frenchman” had been settled “for several years” just three days away, so François sent the man a letter, presumably by an Arikara courier; no response came, and the brothers continued on.52

The mysterious Frenchman may or may not not have been Pennesha Gegare. Other Europeans circulated much as he did and then slipped through the cracks of the historical record.* These fleeting allusions, like Pennesha’s story, are representative of the fitful, weakly documented contacts between Mandans and Europeans in the eighteenth century.

MANDAN VILLAGES, CHRISTMAS DAY, 1773

A trader named Mackintosh is another case in point. He arrived at the Mandan towns on Christmas Day, 1773, and we know about his adventure only because David Mitchell, a two-term U.S. superintendent of Indian Affairs, described it in a letter in 1852 and dated it to 1773. Mackintosh’s own account is a most elusive document, and if it still exists, scholars do not know where. If we could find it, it might shed light on missing years in the annals of Mandan history. But all we have is Mitchell’s summary.

Mackintosh “set out from Montreal, in the summer of 1773,” he said, “crossed over the country to the Missouri river, and arrived at one of the Mandan villages on Christmas day.”53 Mitchell expressed doubts about what came next, calling it “a long, and somewhat romantic description of the manner in which he was received,” with lengthy praise of “the greatness of the Mandan population, their superior intelligence, and prowess in war.” If Mitchell was not impressed, Mackintosh clearly was. “He says, at that time the Mandans occupied nine large towns lying contiguous, and could, at short notice, muster 15,000 mounted warriors.”54

Fifteen thousand warriors translates to a total population of sixty thousand divided among nine towns. The figure is inconceivable for the Mandans alone, and this was Mitchell’s view too: “I am inclined to think that the statistics of the author whom I have quoted are somewhat exaggerated; and at the time he visited the Missouri, the Mandans were not so numerous as he represents.” Perhaps Mackintosh meant fifteen thousand Mandans overall. Or perhaps he lumped the Mandans together with some other village tribe—the Hidatsas, the Arikaras, or both. Visitors often failed to distinguish between the Mandans and the Hidatsas.55

Mitchell’s skepticism seems warranted, but he recognized a fundamental truth in the Mackintosh “narration”: The Mandan towns of 1773 “must have been powerful communities, at least so far as numbers could make them powerful.”56

ST. LOUIS, SPANISH LOUISIANA, CHRISTMAS EVE, 1774

It was another Christmas Eve. To the north the ephemeral Mackintosh had approached the Mandan villages just one year earlier. To the east, a year later, Continental troops were to hold Boston under siege as Anglo-American colonists whispered about independence from Britain. For residents of St. Louis in 1774, however, the occasion was the blessing of their first church bell. Everyone came out for the event. The ceremony—though paltry compared with the Okipa—instilled residents with a similar sense of unity, conviction, and pride, and that night they voted to build a real church to replace the little log building now housing the congregation.57

St. Louis was only ten years old. Established in 1764 by the teenager Auguste Chouteau and his stepfather, Pierre de Laclède, the colony had its roots in the French communities of New Orleans and lower Louisiana, whose settlers named their new, upriver post after Louis IX, the thirteenth-century crusader who was patron saint of the man they believed was their current king, Louis XV. But unbeknown to the St. Louis founders, Louis XV was their king no longer. In 1763, at the end of the French and Indian War, he had given the huge expanse of Louisiana to Spain. So remote was St. Louis that the news barely fazed the settlement’s French habitants when it eventually arrived; and the first representatives of the Spanish crown did not turn up until 1767.58

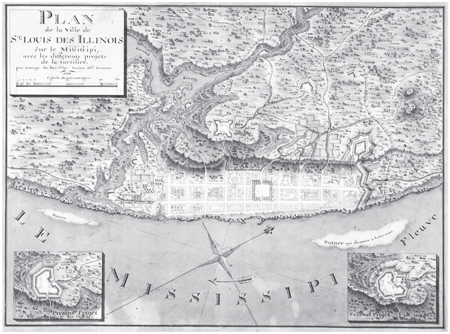

Now, as a crowd gathered to bless the church bell, the town had the appearance of prosperity. The settlement sprawled lengthwise along the Mississippi River just below the mouth of the Missouri. Its nicest homes—including that of Pierre de Laclède—lined the waterfront. A Spanish census from 1773 counted some 637 residents, including 193 slaves, in the village’s 115 homes. In both its size and its central preoccupation, the town was comparable to some of the Mandan settlements upstream: “Commerce,” writes the historian Jay Gitlin, “lay at the heart of this place.”59

Figure 6.4. Plan de la Ville de St. Louis des Illinois sur le Mississippi, map by George de Bois St. Lys, 1796.

Auguste Chouteau and his descendants dominated the St. Louis fur trade for years. Their main concern was commerce with the Osages, who lived southwest of them, along the Arkansas River. Rumors about Mandans abounded, but even when the French turned their sights northward, it took nearly two decades for St. Louis traders—at least those we know about—to reach the upper Missouri. Not until 1792 would Jacques d’Eglise, a Frenchman under Spanish license, trade a paltry selection of goods among the Mandans.60

In the meantime, the villagers faced an affliction that challenged every aspect of Mandan life. It even challenged life itself.