Figure 8.1. The David Thompson Memorial overlooking the Souris River valley in Verendrye, North Dakota. The Great Northern Railway, which merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad in 1970, erected the monument in 1925.

EIGHT

Convergences: Forces beyond the Horizon

VERENDRYE, NORTH DAKOTA, AUGUST 10, 2002

I visited the David Thompson Memorial on a cool, gray afternoon with a wind-borne mist that refused to turn into rain. The memorial, erected in 1925, stands in Verendrye, North Dakota, in the north-central part of the state, twelve dirt-track miles from U.S. Route 2. The monument is a simple granite globe, five feet in diameter, marked only by symbolic grooves of latitude and longitude—the invisible but closely calculated lines, circling the earth, that David Thompson used to track his travels and map huge portions of North America. A quarter of a mile west, behind the sphere, clumps of willows and cottonwoods line the banks of the Souris River. There is a railroad trestle too, crossing the stream that Thompson had to walk across in freezing winter weather two centuries ago.

A hillside behind me bears an iron arch marking the entrance to the Verendrye town cemetery. There are still farmsteads nearby, but the hamlet of Verendrye no longer exists, gone the way of Double Ditch. Instead, there is only one empty brick wall near the railroad tracks. The roof and other three sides of the building crumbled long ago, but the elegant facade stands over the prairie. Few tourists visit this remote monument. Indeed, David Thompson is unknown to most U.S. residents, as are the Vérendryes.

It was reading Thompson’s Narrative of his explorations in the American West that drew me here.1 As I walk around the imposing sphere, planted on the plain near the center of the continent, I try again to think through the disparate pieces of the Mandan puzzle that seem to come together in the two eventful decades that followed the collapse of 1781.

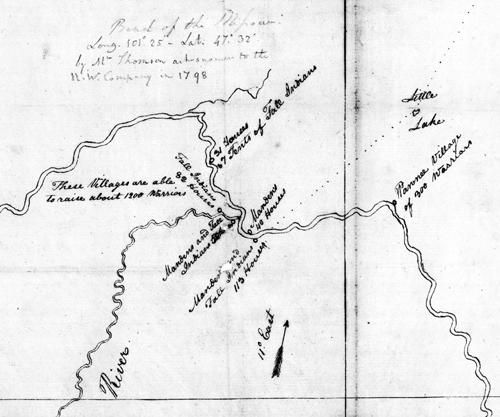

I imagine Thompson, who started his life in London in 1770 and visited the Mandans in 1797–98, squinting through his sextant, his hands numb with cold. His astronomical readings and calculations were the first to place the villagers properly on European maps. He plotted his route between Canada and the upper Missouri with a dotted line that Meriwether Lewis later copied when he made a facsimile of Thompson’s chart.

But other lines, from other directions, also converged toward the Mandan villages as the eighteenth century became the nineteenth. As I walk away from the globe, the mist in my face, I envision lines on some two-hundred-year-old map that link the villagers to people in Haiti and Canada, St. Louis and Washington, Nootka Sound and Paris, France.

Figure 8.2. Meriwether Lewis after David Thompson, Bend of the Missouri River, 1798 (detail). The route of Thompson’s return trek is the dotted line extending toward the top right. The Knife River flows into the Missouri from the bottom left. Five Mandan and Hidatsa (Fall) Indian towns are indicated. The “Pawnee Village” downstream is the short-lived Arikara town constructed near the Mandans and Hidatsas after the smallpox epidemic of 1781. Thompson, who did not visit it, placed it on the wrong side of the river. Lewis made this copy of Thompson’s chart while planning the famous expedition of 1804–1806.

UPPER-MISSOURI VILLAGES AFTER THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Non-Indian visitors came like pilgrims, first in a trickle, eventually in a stream trekking southward from Canada. Thanks to their sojourns in the Knife River towns, the Mandan historical record takes on a new richness in the late 1780s. We get not just glimpses but longer looks and multiple eyewitness accounts of events and lifeways on the upper Missouri.

Most of these interlopers were fur traders who left little record behind. They included men like the one we know only as Ménard, whose arrival dates to some time between 1778 and 1782, and the North West Company trader Donald MacKay, who visited the Mandans in the spring of 1781.* These men might even have witnessed the earliest eruptions of smallpox among the Mandans.

After 1785, some of the visitors came from the Canadian Fort Pine, situated on the Assiniboine River far upstream from La Vérendrye’s old post on the same waterway. A Scottish-born trader named James Mackay made his way from Fort Pine to the Mandans in the winter of 1787. The reception he was given hearkened back to La Vérendrye’s encounter forty-eight years earlier: The Indians intercepted him at a distance and carried him into town “between four men in a Buffaloe Robe, to the Chiefs tents.” They feasted and feted him, treating him with “all the Affability possible.”2 Hospitality was part of the Mandan allure.

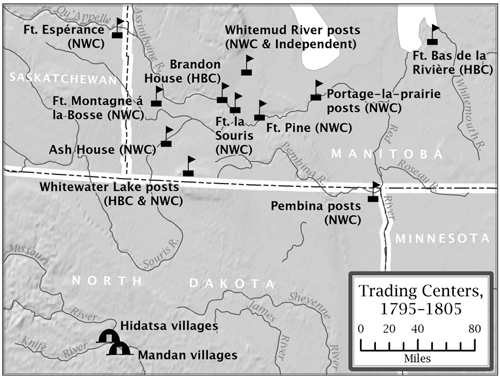

At the time of Mackay’s visit, the villagers still got most of their European-made goods from the “other nations” who came to them, these “other nations” having gotten “them from White People.”3 But direct trade with whites increased when fur-company trading posts proliferated on the Canadian prairies and their employees came south to the villages. The Montreal-based North West Company took over Fort Pine not long after its construction in 1785. One hundred miles upstream, the same outfit built Fort Espérance on the Qu’Appelle River in 1787. Then, in a flagrant and characteristically belated effort to horn in on the upper-Missouri trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company built Brandon House just a few miles away in 1793.

Soon representatives from both enterprises made regular jaunts to the Knife River towns. Between James Mackay’s journey of 1787 and the arrival of Lewis and Clark in October 1804, at least thirty-nine parties of traders—Nor’Westers, Hudson’s Bay men, and independents—visited the Mandans and Hidatsas from Canada’s Assiniboine River region.4

The pox and the Sioux might have reduced the Mandans’ numbers, but their marketplace savvy was undiminished. With traders competing for their business, the villagers drove prices skyward, demanding “Double the Value” for the peltries they sold. Grand greetings, adoption ceremonies, and gift exchange had marked the earlier encounters with Canadian traders, but the Mandans learned over time that direct commerce with these whites was about commodities first and relationships second. This is not to say that the villagers abandoned their traditions of hospitality completely. If Mackay is correct, they simply scaled them back. The traders’ greed, he said, “convinced the Indians that it was not necessary to show so much friendship to the whites to entice them to return to them with goods, seeing that the only object that brought them was to procure pelteteries.”5

After 1763, competition between the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies in the Canadian interior had led to what one scholar has called “a ruthless exploitation” of the beaver—which had been, traditionally, the centerpiece of the fur trade in North America. By 1795, many areas along the Saskatchewan River had few beavers left.6 Muskrats and martens helped to fill the trade void, but the value of their skins paled next to that of beaver, prized by European hatmakers because the barbed hairs of its undercoat pressed into a superior felt.

Mandans and Hidatsas had some access to beavers in the wooded riparian bottomlands where they lived and worked, but their commerce with white traders consisted mostly of corn, horses, bison robes, and wolf and fox skins.7 The items they obtained in return included firearms, arrow tips, awls, tobacco, mirrors, paints, and decorative beads. The prestige of their towns may have seduced the European and American traders who bartered such goods into wishful thinking; records indicate that the furs they collected directly from the villagers in fact made only a tiny contribution to the overall Canadian trade.8

MANDAN VILLAGES, 1792

Traders also came from St. Louis, on a trip that covered a thousand miles as the crow flies and nearly twice that if one followed the Missouri River’s meandering course. Jacques d’Eglise, a Frenchman licensed by Spain to hunt far up the Missouri, reached the Mandans in 1792. When he returned, he told Zenon Trudeau, the Spanish commandant in St. Louis, that he had found them living in “eight villages, which are a half league distant from each other”—an observation suggesting that either d’Eglise or Trudeau did not distinguish between Mandans and Hidatsas. Their combined population came to “four or five thousand.”9

Despite the ravages of smallpox and the Sioux, the Mandans’ trading empire impressed d’Eglise. He told Trudeau they had “saddles and bridles in Mexican style for their horses,” an indication of their “communication with the Spaniards, or with nations that know them”—that is, Spanish settlers in New Mexico and the Indians who traded with them. He also described Mandan ties to British posts farther north, on the Assiniboine River. He had met the trader Ménard among the villagers, learning from him that these posts were “only fifteen days’ march” from the upper Missouri and “that the Mandans trade directly with the English.”10

Lastly, d’Eglise told Trudeau, the Mandans were “white like Europeans, much more civilized than any other Indians.” This made them sound much like the white-skinned Indians Pierre de la Vérendrye had heard about in the 1730s. La Vérendrye had initially been disappointed when the Mandans turned out not to be white, though within days he too was seeing “light-complexioned” Indians, some with “blond or fair hair,” in their midst.11 Whether these reports expressed reality, wishful thinking, or deception is impossible to ascertain, but the belief persisted that Mandans were white—even, possibly, descendants of Welshmen. Before long, this unlikely supposition even drew an odd Welshman up the Missouri River.12

NOOTKA SOUND, 1789

A clash between Spanish and British sea captains in a small body of water off the western shore of what we now call Vancouver Island might seem far removed from the upper-Missouri villages, but this odd little imperial spat in a distant region had consequences that stretched even to the heart of the world.

In 1789, a Spanish navigator named Esteban José Martínez was ordered into what we now know as Nootka Sound and told to seize the men, ships, and property there connected to an English fur trader named John Meares. The Spanish claim was that Meares, who had built lodgings and a breastwork on shore, was operating illegally in Spanish territory. The British counterclaim was that despite Spain’s many sailing expeditions to the Pacific Northwest coast, it could not stake a claim to territory without having made some gesture of occupation, which it had not done. The wrangling went on for years, escalating into an international incident that brought the two European powers to the brink of war.

The entire controversy highlighted the disconnect between ambition and implementation in Spain’s New World empire. Stretched far too thin, Spanish forces had still not established firm footholds in the Pacific Northwest, where they hoped to dominate trade with Asia, or in the Louisiana territory above St. Louis, where they hoped to find furs and a Northwest Passage. Jacques d’Eglise’s 1792 report of British traders from Canada circulating among the Mandans suggested that there too, as at Nootka, Britain had designs on territory claimed, though not occupied, by Spain. The Knife River towns were awash with British goods, were serviced by British traders, and were practically oblivious to the existence of St. Louis. Without a physical presence, Spain’s dominion existed only on paper.

A Spanish post among the Mandans and Hidatsas could, therefore, solve many problems at once: It could divert fur-trade profits from Britain to Spain; it could secure territorial claims; and it might even serve as a stepping-stone along an overland route to the Pacific. The hunt for a Northwest Passage was alive and well. All it took was one Spanish adventurer to find the way.

The attempt began in St. Louis. Its roots, however, extended not just to Spain but to Wales.

NEW YORK, JUNE 1789

James Mackay, the peripatetic Scottish-Canadian fur trader who visited the Mandans in 1787, was a hard man to please. He had worked for both of Canada’s two major commercial concerns—the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies—as well as for the independent trader Donald MacKay. Nothing seemed to work out. He filed suit against MacKay in 1789, abandoned his allegiance to the British crown, and ended up in New York.

New York was bursting with activity in the summer of 1789. The city’s population of more than thirty thousand surpassed that of the Mandan towns at their pinnacle.13 But numbers alone were not what set the city abuzz. In the aftermath of the ratification of the United States Constitution, members of the new federal Congress gathered in New York for their first official meeting. Their task was daunting. The states had ratified the document, however disliked it was by the population at large, and now it fell to Congress to ascertain what it meant. How would the Constitution be implemented? What would the new government look like?

It was probably in June, while the delegates at Federal Hall on Wall Street grappled with the establishment of an executive branch, that the backwoodsman James Mackay met Don Diego Maria de Gardoqui, Spain’s minister to the United States. The events leading to this unlikely encounter are a mystery. But as a man devoted to the preservation of Spain’s North American empire, Gardoqui was keenly interested in what Mackay had to say about distant parts of his country’s territorial claims. Mackay told him of the “various Indian nations”; he described the upper Missouri River; and he reported that Indians farther west knew of “a river which empties into the Pacific Ocean.” He also showed Gardoqui a map he had drawn, and the Spanish minister appears to have obtained a copy.14

Both men benefited from the encounter. Gardoqui got intelligence pertaining to the northern parts of the giant expanse of Louisiana, and Mackay got an entrée to Spanish officials in St. Louis. They too wanted to know about the tribes and the British traders on the upper reaches of the Missouri River. By 1793, Mackay was in St. Louis himself, living as a Spanish citizen, but then his life took another turn. A year or so later, in the course of a round-trip journey east, he met a man in the Ohio country named Morgan John Rhees.15

Rhees was a Baptist minister, an ardent Welsh nationalist, a fierce republican, and a devoted abolitionist. Visiting Mount Vernon, he had composed a poem beseeching President Washington to liberate his slaves. In Richmond, Virginia, he had argued for emancipation before the state’s House of Representatives.16 Rhees was also on a quest to find a long-lost, light-skinned colony of Indians descended, he believed, from a Welsh Prince named Madoc.

In 1170, according to legend, Prince Madoc had sailed west from Wales and landed in America. By some accounts, he was never heard from again. By others, he left a small colony behind in Mexico or Florida and returned to Wales for more men. Assembling a crew, he once more sailed westward—and this time disappeared forever. His legacy could purportedly be found in the presence of light-skinned, blond-haired, Welsh-speaking Indians in America.*

Despite claims to the contrary, there is no evidence for the truthfulness of the tale. The twentieth-century Welsh historian David Williams put it bluntly: The Madoc myth “produced a voluminous literature,” most of which was “devoid of any value whatsoever.” The story had been promulgated by a bevy of Elizabethan courtiers, cartographers, scholars, and theorists eager to challenge Spain’s claims to America. Their argument was that because Madoc, sailing in 1170, had preceded Christopher Columbus by three centuries, England, not Spain, had territorial prerogative.17

The hunt for the Welsh Indians had moved westward with Anglo-American settlement. By 1794, its focus had narrowed to two Indian peoples: the Apaches of the Southwest and the Mandans of the upper Missouri. James Mackay kept his mind open when Morgan John Rhees bent his ear. Even though Mackay had already visited the Mandans and knew “nothing of a Welch Tribe,” he believed in “the Possibility of their existance.” Rhees gave him “a small vocabulary of the Welch Language written by himself.” He also told him of a fellow Welshman who had gone west to find the elusive tribe on the upper Missouri, a man whose name was John Evans.18

ST. LOUIS, SPANISH LOUISIANA, 1793

The false starts came first, carried out by men heedless of the so-called Welsh Indians but keen to reach the Mandans. Jacques d’Eglise, who had tantalized St. Louis with his 1792 report, set out on another trading venture to the villages in the spring of 1793. His attempt to return to the Mandans overlapped chronologically with the Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie’s transcontinental trek to the Pacific Ocean, a feat that Lewis and Clark were to repeat with more fanfare twelve years later. Unlike Mackenzie, d’Eglise failed, stopped by Sioux and Arikara Indians who forced him to part with his goods many miles downstream of his destination. He returned to St. Louis with barely enough peltries to cover his expenses.19

Next came a St. Louis schoolmaster named Jean Baptiste Truteau. Hard experience usually trumped book learning on the frontier, and in this Truteau was lacking. But he had something that d’Eglise did not: He had sponsors. In 1794, a group of St. Louis residents headed by the Afro-Haitian entrepreneur Jacques Clamorgan set up a fur-trading partnership called the Missouri Company that would tap the resources of the upper Missouri River and, Clamorgan hoped, with luck might even push through to the Pacific.20

With this in mind, the partners sent Truteau with eight men up the river in June 1794. His orders were to “proceed, with all possible foresight, to his destination, the Mandana Nation,” where he was to make “a settlement or establish an agency” for trade, with a fort for protection and buildings “of logs placed upon one another in English fashion.” Then Truteau was to plant an orchard, offer his merchandise with “a very high price on everything,” and push up the Missouri toward “the Sea of the West.”21

Truteau never reached the Mandans. He made it to the Poncas and Arikaras in present-day South Dakota, but no farther. When he returned downriver in 1796, he reported that the obstacles encountered included a serious lack of food and the resentment of the Sioux and Omahas, eager for trade items themselves. The Sioux in particular wanted to halt the flow of goods to their villager enemies along the Missouri River.22

The Missouri Company had not waited idly during Truteau’s two-year absence. Another heavily laden boat set out in April 1795 commanded by a man we know only by the last name of Lecuyer. It too got no farther than the Poncas. Lecuyer claimed the Indians robbed him, but an eyewitness explained the failure differently. Lecuyer, it was said, had no “less than two wives since his arrival at the home of the Poncas” and thus “wasted a great deal of goods of the Company.”23

MANDAN AND HIDATSA VILLAGES, OCTOBER—“MOON OF THE FALLING LEAVES”—179424

While these Spanish efforts foundered, the British ensconced themselves to the north, bolstered by the accomplishments of men like Mackenzie. In October 1794, the mixed-race trader René Jusseaume went south from the Assiniboine River to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages for the North West Company. Once there, eyewitnesses said, he “ran up the English flag and began his trading” while his men built a little trading post between the Mandan and Hidatsa towns. In the weeks and months that followed, the occupants of the post hoisted the standard “every Sunday.”25

Map 8.1. Some of these locations, such as the Mandan villages and Brandon House, were long-lasting trade hubs. Others, such as the Whitewater Lake posts, existed for only a year or two.

We do not know what the Indians thought of this ritual, but to the Spanish officials and Missouri Company partners in St. Louis who learned of the British flag flapping in the prairie wind, it meant only one thing: The British threat was growing.

ST. LOUIS, SPANISH LOUISIANA, AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 1795

Like Morgan Rhees, John Evans was a Welshman. He arrived in St. Louis via London and Baltimore, swearing allegiance to the Spanish crown along the way. His service to Spain would be diligent and honest, but his mission had everything to do with his Welsh heritage. He was hell-bent on ascending the Missouri River to find the Welsh Indians.

When Evans landed in St. Louis and met James Mackay, he was twenty-five years old and had no backwoods experience. He knew nothing of real Indian languages or the fur trade. But the mutual connection to Morgan Rhees gave him an entrée to Mackay, who had contracted with the Missouri Company to launch yet another attempt to reach the Mandans. Thus Evans became Mackay’s right-hand man when the expedition of thirty-two set out in the late summer of 1795, fighting against the Missouri’s current in four boats brimming with wares for the Indians. The Missouri Company intended each vessel’s cargo for a different destination or tribe: one for the Arikaras, one for the Sioux, one for the Mandans, and “one to reach the Rocky Chains [Mountains] with orders to go overland to the Far West.”26

On November 11, 1795, the Mackay-Evans party arrived at the settlements of the Omaha Indians in modern-day Nebraska. With winter closing in, Mackay elected to halt and build a fort there to wait out the season. By spring he had decided to send Evans and a smaller party ahead without him. Their charge was to proceed to the Mandans, to the Rocky Mountains, and then to the Pacific Ocean. They were to keep their eyes peeled for unicorns—“an animal which has only one horn on its forehead”—along the way.27

They set out on June 8, 1796.28

KNIFE RIVER VILLAGES, SEPTEMBER 23, 1796

John Evans found no unicorns, but he did find the Mandans. His approach from the south would have been unexpected for them. Despite the visit from Jacques d’Eglise four years earlier, non-Indian guests from downriver were rare; the pattern familiar to Mandans was for traders—the very traders who worried St. Louis’s merchants and officials—to come from British posts to the north.

What goods did Evans bring? How did they compare with those offered by the northerners? We don’t know for sure. But as the archaeologist Raymond Wood has said, Evans’s wares probably differed little from the merchandise carried by other St. Louis traders. Jean Baptiste Truteau’s stock, for example, included tobacco, textiles, and an assortment of metal items such as guns, awls, hatchets, kettles, and ammunition.29

The sharp-trading Mandans would have appraised such items for both quality and price. They already benefited from the competition among independent traders, Hudson’s Bay men, and Nor’West men. What could they lose from adding another competitor to the mix? They welcomed Evans with the same hospitality they afforded all their guests.30

Yet some aspects of Evans’s behavior were odd, at least when measured against the conduct of other white traders. He apparently delivered a speech invoking “their Great Father the Spaniard” and handed out “medals & flags” and other “small presents.” Then, after a few days, he “took possession” of Jusseaume’s trading post between the Mandan and Hidatsa villages. Jusseaume was gone at the time, and the records do not indicate whether the depot was occupied, but the trader’s children and Indian wife were somewhere in the area. Evans meant to make a statement: “I instantly hoisted the Spanish flag which seemed very much to please the Indians,” he reported.31

Ten days later, when a party of British traders arrived from Canada, Evans intercepted them. He was doing his best to protect the interests of his Spanish sponsors, though he lacked the military resources to keep the British away. “I did not strive to oppose their arrival, nor of their goods,” but instead found a way “to hinder their Trade and some days after absolutely forced them to leave the Mandane Territory.” The departing traders carried with them a declaration from James Mackay that explicitly banned “all forigenrs whatever” from entering or trading in the “Chartered dominions” of Spain. When they delivered this document to their superiors on the Assiniboine River, it elicited mild derision but little concern.32

The British continued going south to the upper-Missouri villages regardless. A North West Company party headed there in November 1796, and a Hudson’s Bay Company party set out in January 1797. The Indians too paid little mind to Evans’s claim of Spanish sovereignty. They were pleased whenever anyone came to trade. The villagers gave some Hudson’s Bay men who turned up in February 1797 the classic Mandan greeting: According to the Brandon House master James Sutherland, they “wer[e] met by above 300 Indians who carried their Sleds on their Shoulders into the vilage, so fond wer[e] they of the English.”33

Evans was “cival” to his competitors, but he still “would not permit them to Trade with the natives.” The parties worked out a technical compromise, whereby Evans himself bought the British goods, exchanging them for furs he had already taken in. But the Indians were “highly displeased” with these proceedings.34

When in March 1797 René Jusseaume came back to find Evans installed in what had once been his own trading post, he reportedly urged the Indians to kill the interloper and “pillage” his property. But Mandans and Hidatsas considered their towns safe havens for all guests and rejected Jusseaume’s inducements to act; according to Evans, they “shuddered at the thought of such a horrid Design.” A few days later, Jusseaume tried to shoot Evans when his back was turned, but Evans’s interpreter intervened and the Indians hauled Jusseaume away.35

This sequence of confrontations may have amused the Mandans at first, but apprehension soon took over. Theirs was a free-trade policy, embracing all comers. Even the Sioux sometimes bought and sold goods among them. Evans’s claim of sovereignty was absurd. Matters soon came to a head. Our admittedly one-sided source—the master of Brandon House, James Sutherland—reported in April that Evans’s efforts to control the trade had “set all the Indians out against him” so vehemently that “he was obliged to set off with himself and all his men down the River.” The townspeople threatened to kill him if he did not leave.36

John Evans had strained villager hospitality to its limits. He had not reached the Pacific. And he had not found the Welsh Indians. By May 1797, he was back in St. Louis. Morgan Rhees later shared publicly what Evans wrote to him about all this: “With reference to the Welsh Indians, he says that he was unable to meet with any such people; and he has come to the fixed conclusion, which he has founded upon his acquaintance with various tribes, that there are no such people in existence.”37

Seven years after Evans’s disappointment, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out on their own Missouri River odyssey. They carried with them six map sheets that detailed the waterway with extraordinary accuracy as far as the Mandan villages. The charts were the best in existence at the time. The cartographer was James Mackay, and the details from Nebraska to North Dakota were based on the surveys of John Evans.38

ON THE SOURIS RIVER PLAINS, NOVEMBER 1797

Travel on the northern plains was perilous. David Thompson learned this by hard experience in November and December 1797, when he made his way to the Mandan and Hidatsa towns from John Macdonnell’s North West Company post on the Assiniboine River.

The weather turned ugly three days into the trip. “Most dreadfully cold,” Thompson wrote. Before a roaring fire one evening, he and his men struggled mightily to stay warm. They killed two bison cows, but the wind blew so hard that only “with difficulty” could they “stand to cut up” the meat. Thompson checked his thermometer at 7 a.m. and 9 p.m. Each time, it read −32 degrees Fahrenheit. Already he had frostbite on his nose.39

For four days, the wind and cold kept the men frozen in place. On the fifth day, the cold relented, and they might have moved on, but the gale continued and brought a payload of snow that blew into “high Drifts” and kept them “from seeing a ¼ M before us.” Without visible landmarks or celestial reference points, navigation on the treeless plains was impossible.40 They hunkered down and waited another day.

Thompson was no novice outdoorsman. He came of age in the Hudson Bay hinterlands, slipping past polar bears on a trek to York Factory when he was fifteen, helping to build a new inland trading post when he was sixteen, and wintering with the Piegan Blackfeet at the foot of the Canadian Rockies when he was seventeen. (In 1811, he was to traverse those mountains in January.) But this trek to the upper Missouri was different. Snow was not the problem, except when it hampered visibility; North Dakota’s semiarid plains typically get only three or four feet per year.41 The problem was the cold and the wind. A hard gale at subzero temperatures stopped even the most seasoned travelers on the shelterless prairies.

Thompson’s party consisted of ten men with sleds, dogs, and horses. The explorer’s companions were mostly “free traders” who got their “venture” on credit from the British fur companies and hoped to profit from bartering it when they got to the villages. One was an Irishman named McCrachan who traded regularly on the upper Missouri. Another was René Jusseaume. The remaining seven were French-Canadian voyageurs.42

The men set out again on December 4, crossed the Souris River, and camped in a stand of ash, oak, and elm beside an icebound stream. The next morning dawned clear. With easy traveling ahead of them, they anticipated reaching the Turtle Mountains, an important way station on what is now the Manitoba–North Dakota border, by evening. But it was not to be.43

At midday, “the wind changed to a Gale,” and by evening the men faced another full-fledged storm. Darkness set in. “Several of the men were for putting up in the open Plain, rather than wander all Night,” but Thompson and others dissuaded them. They made a run back for the trees they had left that morning and then “stumbled on a hammock of woods, almost perished with Thirst.” Thompson’s journal describes their state: “We struck a Fire, and quickly melted some Snow and quenched our Thirst ere we thought of anything else, some took a mouthful, others quite overcome with Fatigue threw themselves down on the Snow and slept out the Night.” The next day, they were again “obliged to lay by.”44

Figure 8.3. The gentle rise of the Turtle Mountains, extending for twenty miles along the North Dakota–Manitoba border, viewed from the south. Although the mountains rise less than a thousand feet above the plains, their amply treed terrain has provided shelter to wildlife and plains travelers for centuries.

And so it went, three steps forward, two steps back. Incremental progress was the best they could hope for. December 10 blew into “a perfect Storm” with wind that “roared like distant Thunder” and “such terrible Drift that the Earth & Skies seemed confounded together.” One man lost his dogs, his sled, and his venture. Another collapsed, was carried briefly, and was then left to die so the rest could live; he eventually roused himself and crawled to the others. Some lapsed into despair, certain they could not survive the night. But survive they did, “thankful to Providence” and thankful as well to a “hammock of Saplings” that shielded them from the wind.45

By December 11, most of the men had frostbite. December 12 was “a Stormy Evening with Snow,” December 13 “a very stormy Night and Day, with high Drift, wind North.” Three days later, “a most terrible Gale with excessive high Drift” forced the men into a stand of woods, without which they “must have perished.” December 18 dawned clear but then turned into “a most terrible Storm.” As for December 19, “I never saw a worse Day in all my life,” Thompson wrote. “The roar of the wind resembled the noise of the waves of the Ocean when dashed on the Rocks by continuous Storm.” More wintry weather buffeted the travelers the morning of December 21, and a “most terrible Storm” struck December 26. By this time both men and dogs were “next to starving.” Four days later, they reached the Knife River towns.46

The return trip was only slightly less taxing, taking Thompson’s party twenty-four days rather than the full month they spent outbound. They once again endured parching thirst, “having no wood” to “make a Fire to thaw the Snow.” They “lay by” again and again due to “bad stormy snowy” weather. They suffered through a “most terrible Storm” in an open hut. They languished for lack of meat. “Eating Corn” was Thompson’s refrain. And on January 22, they sat through a snowfall so thick it almost suffocated them. “This is beyond Doubt the worst Day I ever saw in all my Life,” Thompson wrote. But he was luckier than the others. The day before he had stumbled across “the Marrow Bone of a Buffaloe which had been pretty well Knawed by a Wolf.” The bone sufficed as his “allowance” through the storm.47

Not all trips from the Canadian trading houses were so difficult. Thompson himself said that in “good weather,” it was “a journey of ten days.” From Fort Pine, according to Peter Pond, it took twelve. The season itself mattered little, but variable seasonal conditions mattered much—winter cold, wind, and snow, and summer heat, mosquitoes, prairie fires, and muddy, low-lying bogs. Winter travel required dogs and sleds; summer travel required horses. But because competition was keen and the winter trade yielded the best furs, there was a special incentive for making the trip in the colder months of the year.48

As an old man, Thompson waxed philosophical about his trip to the Mandans, wondering about “the cause of the violent Storms” that “desolate this country.” The plains were like the open ocean, he believed, with “no Hills to impede” a storm’s course or “confine it’s action.” Treeless terrain, summer grassfires, and winter storms combined to make the country appear unsuited for substantial European habitation. “These great Plains appear to be given by Providence to the Red Men for ever,” he wrote, “as the wilds and sands of Africa are given to the Arabians.”49

KNIFE RIVER VILLAGES, DECEMBER—“MOON OF LITTLE FROST”—179750

David Thompson’s purpose in visiting the upper-Missouri towns had been twofold: to talk the Mandans and Hidatsas into visiting the North West Company’s Manitoba trading posts themselves and to map the country and ascertain the geographical coordinates of the Knife River villages.

Thompson was a surveyor, explorer, and mapmaker extraordinaire, in part because of his respect for Indian knowledge. At one Hidatsa town he drew some maps “before the Natives, who ex[amine]d. & corrected them.” He was also a keen and literate observer, judgmental at times but unshakable in his inquisitiveness about Indian history, knowledge, and life. His voluminous writings offer the fullest account of the Mandans since La Vérendrye’s. “My curiosity was excited,” he said, “by the sight of these Villages containing a native agricultural population; the first I had seen.”51

Since Thompson visited in winter, he found the Mandans in their warmest clothing. The men wore waist-high leggings, long shirts with sleeves, and “always a Bison Robe.” The women “looked well” in their full-length dresses “of Antelope or Deer leather,” cinched with a belt and complemented by “short leggins to the knee.” Both sexes wore bison-skin shoes “with the hair on.” Thompson found the villagers “handsome,” “well limbed,” and “fully equal” in stature to Europeans.52

The villagers housed their guest in an earth lodge, graciously offering him a wood-framed bed, “soft and comfortable,” to use as his own. His men got the same treatment, dispersed among three different towns. Thus Thompson could well describe earth-lodge architecture and the layout of a typical home, with its interior horse stalls, hide-and-wood furnishings, immaculate fireplace, and gentle illumination via the smoke hole.53

Visiting each of the Mandan and Hidatsa towns during his ten days at the Knife River confluence, Thompson thought they looked “like so many large hives clustered together.” As he saw it, there was “no order” to the houses—no parallel streets, no “cross Streets at right angles.”54 But one culture’s chaos is another’s defensive strategy. When he sketched the street plan of a European-style town for the Indians, they “shook their heads” and wondered at the lack of common sense. How could such settlements be defended? “In these straight Streets,” they said, “we see no advantage the inhabitants have over their enemies. The whole of their bodies are exposed.”55

Thompson also counted earth lodges. His tallies are fraught with problems, and he contradicted himself in his journal and his longer Narrative, but some conclusions are possible. The combined population of the five Knife River towns was in the range of 2,850 to 2,946, with the Hidatsas predominating: 1,330 to 1,730 Hidatsas, and 1,216 to 1,520 Mandans.56

The numbers reveal a tragic reality. The Europeans and European Americans who visited the villagers in the 1780s and 1790s found the Mandans to be lively, friendly, and prosperous, but still, they were refugees, and over the previous three centuries they had lost 75–90 percent of their population.57 They had preserved their rituals and their lifeway only through diplomacy, determination, and the inspirational guidance of leaders such as Good Boy.

ARIKARAS AND MANDANS, 1797–98

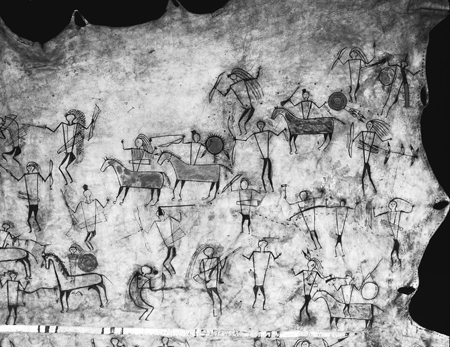

It took several years, but the truce that accompanied the Arikara move to the Painted Woods crumbled and the status quo reasserted itself: in 1798, Thompson reported, the Arikaras were again at odds with their Mandan neighbors. Surviving records say nothing of the reason for the conflict, which occurred in the summer of 1797, but the clash itself was for the ages. One report of it comes from Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian resident trader who had arrived among the Mandans that very year. Decades later he told Prince Maximilian that “1300 or 1400 Sioux, united with 700 Arikkaras, attacked the foremost Mandan village.” A thousand Hidatsas rushed to assist the Mandans, who “repulsed the enemy, killing more than 100 of them.” Traders from the Hudson’s Bay Company posts on the Assiniboine River heard it slightly differently: The battle, they learned, had involved Crees and Assiniboines as Mandan allies, and had led to the death of thirty Arikaras.58

The clash was the last straw for the Arikaras. Soon thereafter, the Europeans learned, they “moved their villages farther downriver” to the Grand River region below the modern North Dakota–South Dakota border.59

This titanic battle became a part of the Mandans’ own historical record too, rendered by an unnamed artist on a bison robe, which Meriwether Lewis and William Clark acquired during their stay with the villagers and which they sent to President Thomas Jefferson in April 1805. It was “painted by a mandan man,” Clark explained, “representing a battle fought 8 years Since by the Sioux & Ricaras against the mandans, menitarras [Hidatsas proper] & Ah wah har ways [Awaxawi Hidatsas].” The Mandans, he added, were “on horseback.”60

Figure 8.4. Detail from the Peabody Museum’s painted bison robe. The origin of this robe is uncertain, but it may be the Mandan robe Lewis and Clark sent to Thomas Jefferson from the Knife River villages in 1805. According to Clark, it depicted a great battle that pitted Mandans and Hidatsas against Sioux and Arikaras in 1797.

If this robe painting is the one currently held at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, it captures both the ferocity of the battle and the stylized, evocative qualities of plains Indian art.61 Broad-shouldered warriors, some with muskets, some with bows and arrows, clash in a frenetic melee. Some have the telltale long hair that designates villagers; some ride horses; and some carry painted shields adorned with feathers. Dashed lines indicate the track of airborne bullets and arrows, which protrude dramatically from the bodies of the wounded. A white-and-yellow band of decorative quills, undoubtedly the work of women and typical of Mandan robes, runs horizontally across the middle of the picture. (The hides painted by women featured elaborate geometric patterns, but it was men who made paintings like this one to commemorate heroic actions and historic events.)* Rendered in a flat two-dimensional plane, without depth of field, the Peabody robe exemplifies early historic plains art. In years to come, Indian artists influenced by painters like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer began to incorporate linear perspective and other characteristics of European realism into their work.62

BRANDON HOUSE, ASSINIBOINE RIVER, APRIL 3, 1796

The men at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Brandon House spent April 3, 1796, a Sunday, “religiously.” A warm, westerly wind was a relief after months of winter. But all was not well. At three o’clock, three tired men returned from a harrowing three-month trip to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages. Fate and the weather had taken their toll. They had “been very Unfortunate this Journey indeed,” wrote the house master, Robert Goodwin, in the post journal.63

The losses were tangible. The Hudson’s Bay men had left Brandon House for the upper Missouri on January 1 together with two other traders headed for the same place. They lost four horses on the way and, in Goodwin’s words, nearly “shared the same fate” themselves. One man lost all his personal items and had to pay a North West Company trader to carry his remaining trade goods on a dogsled. All were badly frozen. James Slater “froze his hands so much that the others in the Company was necessitated to button his Cloaths round him.”64 Once they arrived at the Mandans, the traders had had little choice but to barter their goods for necessities. They bought two horses outright from the Indians and a third on credit from René Jusseaume.

When the hard-luck trio arrived back at Brandon House, they had only 120 “Made Beaver” in tow. (The Hudson’s Bay Company used the “Made Beaver” as a currency unit in calculating its prices and trade.) “Had not these unforeseen accidents happened they would have brot home 3 or 400 MBr: at least,” Goodwin said.65

Bad luck and weather afflicted Hudson’s Bay and North West Company traders alike. It is thus small wonder that one purpose for David Thompson’s trip was to convince the Mandans and Hidatsas to come to the posts rather than the other way around. When he met in council with the chiefs at two separate Hidatsa villages, he urged them to visit the North West Company traders themselves.66

Yet the Indians would have none of it. They appreciated “the advantages of [having] a regular supply of their wants,” Thompson said, but “no hopes could be entertained” of their making the trip. It was too dangerous. The Indians knew what the weather could do, but that was not their main concern. The greater obstacle was hostile tribes. Indeed, Thompson himself had fretted about the Sioux while en route to the villages. So too did the Hudson’s Bay men, who did their best to “keep clear of the Seaux’s” on their trading trips to the upper Missouri.67

The Crees and Assiniboines were also a consideration. The activities of men like Thompson were already disrupting their trade. When Thompson and his companions met a party of Assiniboines, the nomads had received him “with kindness” but told him “they did not approve” of his “journey to the Missisourie.”68 As long-standing go-betweens themselves, the Assiniboines disapproved equally of villagers ferrying their own furs to the trading houses. The Hidatsas told Thompson they had “often attempted” the trip but “jealous” Assiniboines consistently “plundered” them. The Assiniboines understood that if the villagers “had free access to our trading Houses,” they might “become too powerful” and threaten their economic security.

Still, Thompson’s coaxing did convince a few Mandans to attempt the journey. And when he returned to the North West Company’s Assiniboine River station on February 3, 1798, he brought four Indians with him: two Sioux women—enslaved captives the traders had purchased—and two Mandan men.69

The Mandan men did not dally when they got to the Assiniboine River. “Highly pleased” with what they were given there, they turned around and headed home the next day, stopping along the way at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Brandon House. Here the postmaster, John McKay, showed them his storerooms and gave them each “a present of a Sword blade and two fathom of Tobacco with other small trinkets” before they went on to the villages in the company of five North West men with eleven sleds of trade goods.70

The cautious villagers made two other probes northward that year. In October, three “Mandall Inds” visited Brandon House and received “a few triffling Articles as a present.” If they brought furs, corn, or horses to trade, there is no mention of it. A few more Mandans arrived at the Assiniboine River posts in November.71 Thereafter, the Mandans and Hidatsas visited only sporadically and mostly let company men and free traders come to them.

The influx of British traders, along with the tentative villager initiatives, destabilized the Mandans’ long-standing relations with the Crees and Assiniboines.* Traders at Brandon House learned on January 20, 1800, that Hidatsas had attacked some Assiniboines near the Turtle Mountains, where the nomads often sought winter shelter. The survivors fled because the attackers promised “to return again.” In the spring, by contrast, the Crees invited Mandans, Assiniboines, and Ojibwas to join them in an attack on the Sioux. But when they all met at a Mandan town to lay out plans, the Sioux turned the tables and launched their own attack; the four-nation alliance defended the town in a battle that lasted all day. Yet the collaboration was temporary. In the summer of 1801, villagers reportedly killed eleven or more Assiniboines farther west, on Saskatchewan’s Qu’Appelle River.72

Belligerent Assiniboines even threatened to keep Brandon House traders from carrying goods to the upper-Missouri townspeople. When five men and as many horses “started for the Mandans” in October 1801, John McKay warned them “to take every precaution to avoid seeing Inds. as the Assinaboils are determined to rob them.”73

SAN ILDEFONSO, SPAIN, OCTOBER 1, 1800

On October 1, 1800, France and Spain signed a secret treaty at King Charles IV’s royal palace in San Ildefonso, Segovia. Louisiana—an expensive, unwieldy albatross for Spain—again became a French possession. The transfer went into effect in 1801, when France met all the terms that King Charles insisted on.

The agreement was an acknowledgment that Spain had been frustrated in its efforts to administer the northern territories it claimed in America. The treaty also revealed the New World ambitions of Napoleon Bonaparte, first consul and military commander of France. Bonaparte envisioned a new French empire in which the immense Louisiana territory would check U.S. expansionism while providing food and fuel to Haiti and other French sugar islands in the Caribbean. But implementing the treaty was not easy. Bonaparte first needed to crush the revolutionary insurgency in Haiti headed by the brilliant former slave Toussaint Louverture.74

The scheme unraveled with astonishing speed. The Haiti slave rebellion had been gaining force for a decade when Bonaparte sent twenty thousand soldiers to take on Louverture’s army in late 1801. They arrested the Haitian leader and shipped him to France, but his black forces rallied, and soon it was the French who were dying in droves, first at the hands of the freedom fighters and then by the tiny, swordlike proboscis of the disease-bearing Aedes aegypti mosquito. Thousands of French soldiers—jaundiced, ravaged by fever, and puking black vomit—succumbed to the yellow fever virus. Napoleon’s vision died with them.75

Now he too needed to get rid of Louisiana.

WASHINGTON, D.C., MARCH 4, 1801

Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration as president of the United States was a famously modest affair. The president-elect walked from his boardinghouse to the newly constructed Capitol as his predecessor, John Adams, slipped out of town. But the occasion was nevertheless momentous: power transferred peacefully from one political party to another for the first time in the history of the young United States.

Jefferson had work to do. He was committed to cutting taxes, trimming the military, and scaling down government, but even as he favored a contraction of federal power, he was also committed to expanding opportunities for the country’s independent farmers. This required land and—in an era when hauling goods overland was costly and slow—some guarantee that U.S. citizens west of the Appalachian Mountains could ship their produce down the Mississippi River and through New Orleans to destinations far and wide.

What would the United States do if France closed New Orleans to American commerce, as Spain had done in 1794? It happened again in 1802, when the Spanish intendant still in charge there refused to let U.S. citizens offload their produce at city docks. Jefferson asked his ministers to France, James Monroe and Robert Livingston, to explore the possibility of purchasing New Orleans for the United States. Livingston made inquiries, and on April 11, 1803, the French foreign minister responded by offering not just New Orleans but all of Louisiana to the Americans.

Jefferson’s ministers scooped it up. They closed the deal on April 30, 1803. In so doing, they vastly exceeded both their authority and their budget. And the end result was that the territory claimed by the United States doubled in size. The Mandan villages had found their way into the successive embraces of three imperial powers in three years. Now they drew the attention of a new cast of characters.

International diplomacy was not the only aspect of these events that had consequences for the people living on the upper Missouri. Robert Livingston, one of the negotiators, was a longtime proponent of steam-powered navigation who had financed the construction of an experimental steamboat. When it went for a test run on the Hudson River in 1798, the engine shook so fiercely that the boiler nearly came apart, and the design was abandoned. But Livingston’s vision remained alive. At some point during his sojourn in Paris, he met the peripatetic artist-inventor-engineer Robert Fulton. On October 10, 1802, they became partners in a new steamboat enterprise. In 1807, it produced a vessel called the North River, which churned its way up the Hudson at five miles per hour. The North River was not the first steamboat to ply American waters, but it was the first to achieve real success.76 Like horses before them, steamboats transformed transportation across the continent.

BRANDON HOUSE, DECEMBER 21, 1801

The violence was implacable. At Brandon House, John McKay learned the details from five employees who had just come in from the Knife River towns, where the villagers were so preoccupied, the men said, that they “cannot hunt on account of their wars.” The traders brought back only three hundred Made Beaver as a consequence.77 The men had spent less than three weeks on the upper Missouri, but they had borne witness to carnage. One war party returned with 150 horses and eight Shoshone slaves: “They destroy’d 18 Tents of them in a battle close to the Mandan Village.” In another encounter, thirty-eight Sioux had died. A trader named James Slater went “to the spot where the battle was fought & counted 19 heads the rest were taken away by the Wolves.” And, the day before the men set out to return, “the Mandans killd 11 Assinaboils within half a mile of their Village.” The Mandans, it was said, brought home the heads and “several other parts” of the victims’ bodies to be eaten “by the dogs.”78

It is no surprise, perhaps, that when McKay tried to get his men to return to the upper Missouri a month later, they initially refused. “I must own the Journey is dangerous,” he admitted, since the villagers and the Assiniboines “are at war.” After three days of coaxing, the men relented. Loaded with goods, they started across the prairies on January 18, 1802. But the weather turned bad—and the men turned back—that very day. Spooked by the elements and enemies alike, they dug in their heels. This time there was no persuading them. “This has put a stop to the Mandan trade this year,” McKay noted.79

Direct trade with the Mandans eventually resumed.80 So too did peaceful relations between villagers and Assiniboines. By the time Lewis and Clark reached the upper Missouri in 1804, the Assiniboines were welcome visitors and trading partners once again. The villagers, it appears, had abandoned their tentative treks to the northern posts.

As for the procession of white interlopers horning in on the carrying trade, the Assiniboines may have concluded that the British operators were too few to jeopardize their own position, and they may also have adapted as the demand for firearms at the Mandan-Hidatsa distribution centers grew.

David Thompson had observed in 1798 that “Guns were few in proportion to the number of Men” among Mandan and Hidatsa villagers. But the Assiniboines played their markets adeptly. By 1805, they had begun to get weapons from new trading houses on the Red River as well as the older establishments along the Assiniboine. A report reached Brandon House in February 1805 that the Mandans and Hidatsas had “132 new Guns, all from Red River.” The Brandon House postmaster complained that the Crees and Assiniboines who came to trade were “always in want” of guns. “As fast as they take them in debt they give them away to the Mandals or Big Bellies [Hidatsas]. they get nothing in return but Indian Corn and Buffalo Robes.”81

The villagers in turn became gun dealers in their own right, arming the Crows, Cheyennes, Arapahos, and other western peoples who came to their towns. The fur trader Alexander Henry reported that a band of Crow Indians visited the upper Missouri in the summer of 1806 with “great numbers of horses, some skins and Furs and Slaves” to exchange for “guns Ammunition, Tobacco, Axes &c.” They had, he said, “no other means of procureing European articles than by getting them from those Villages.”82

Henry’s description makes the commerce between villagers and Crows seem one-sided, but it was not. The British trader François-Antoine Larocque, who traveled to the Yellowstone country and Big Horn Mountains with a band of Crow Indians in the summer of 1805, saw that the Crows bought horses “very cheap” from the western Indians, then sold them “to the Big Bellies [Hidatsas] and Mandans at duble the price. He is reckoned a poor man that has not 10 horses in the spring before the trade at the Missouri takes place, and many have 30 or 40.” At that point, the Crows “had as yet given no Guns or Ammunition to the Flathead Indians in exchange for horses.” But thanks to the weapons flowing through the Knife River towns, the Crows were themselves well armed. “This year as they have plenty they intend giving them some,” Larocque said.83

The Mandans, in fact, had objected to Larocque’s journey west. The guns that the Crows sold to the Flatheads, Shoshones, and other nations of the Rockies were purchased from the Mandans, after all, and Larocque’s trip raised the possibility that British traders would bypass the villagers entirely, undermining their Crow trade and directly arming their Shoshone enemies. “They asserted that if the white people would extend their dealings to the Rocky Mountains, the Mandanes would thereby become great sufferers,” Charles McKenzie wrote. Not only would they lose out on direct and indirect commerce with the distant tribes, “but in measure as these tribes obtained arms they would become independent and insolent in the extreme.”84

WASHINGTON, D.C., JANUARY 18, 1803

With no knowledge of the spectacular acquisition the French were about to offer his ministers in Paris, President Jefferson submitted a confidential proposal to Congress on January 18, 1803. It had to be kept secret since it involved Louisiana. “The river Missouri, & the Indians inhabiting it, are not as well known as is rendered desirable,” he wrote. It was known, though, that these Indians already had a prosperous trade with the British, themselves encroaching on French-claimed land. Shouldn’t the United States get in on the action? The Missouri River might even provide access by “a single portage” to the “Western Ocean.”85

What Jefferson had in mind was an expedition. He believed “an intelligent officer, with ten or twelve chosen men” might open U.S. trade and a Northwest Passage all at once. The cost would be “two thousand five hundred dollars.”86 It seemed a bargain, and Congress approved.

Jefferson had already picked his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead the undertaking. As preparations moved forward, Lewis invited a fellow Virginian, William Clark, to join him as cocaptain. “I will chearfully join you,” Clark replied on July 18.87 Ten months later, after venturing down the Ohio River, the expedition set out from St. Louis on the muddy Missouri.