NINE

Hosts: The Mandans Receive Lewis and Clark

HEART RIVER CONFLUENCE, UPPER MISSOURI RIVER, OCTOBER 20, 1804

Working their way up the Missouri River, President Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery entered the old Heart River homeland on October 20, 1804. Here, from their two pirogues and a 55-foot keelboat, they viewed the crumbling Mandan villages that still lined the riverbanks. “I saw … old remains of a villige on the Side of a hill,” wrote Meriwether Lewis of the now-silent site of On-a-Slant. On the other side of the Missouri, just upstream from that once-prosperous location, the men passed a “verry Cold night.” The next day, a quarter-mile of travel brought them to the Heart River itself. William Clark noted in his journal that the stream’s mouth was “about 38 yards wide” and discharged “a good Deel of water.”1

The expedition did not probe this western tributary or the smaller Cannonball River a short distance below it. But someone—perhaps the Arikara chief Toone, who traveled with the Corps to the Mandans—told Clark that an oracle stone could be found upstream. The surface of this stone, reported to be “about 20 feet in Surcumfrance,” bore raised lichen markings that changed over time, and in these patterns, the Mandans read their future. They visited it “every Spring & Sometimes in the Summer” to learn “the piece or war which they are to meet with” and “the Calemites & good fortune” to come.2

A generation after Lewis and Clark, Prince Maximilian also heard about the enigmatic outcropping, which overlooks the Cannonball River in what is today Grant County, North Dakota. Native peoples still use it in the twenty-first century. Maximilian described the way it worked: Visitors made a few small offerings—“small pieces of cloth, and such”—before approaching the venerable stone; then, in the “impressions and figures” on its surface, they found prophecies of events to come. Mandans and Hidatsas both used the site, washing the stone and singing, fasting, and smoking for days as they waited for its revelations to emerge.3

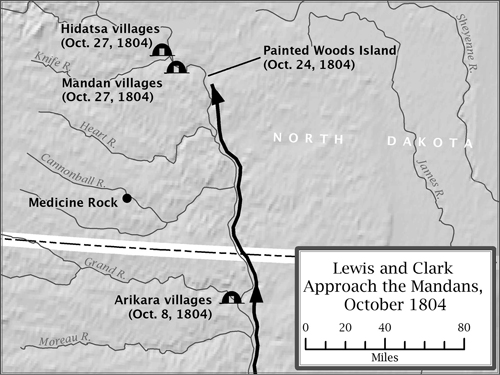

Map 9.1

In June 1794, the lichen on the rock had produced the image of a strange building near a Hidatsa village at the Knife River. The Indians all wondered what it meant. They had their answer four months later, when the fur trader René Jusseaume built his little trading house between the Mandan and Hidatsa towns.4

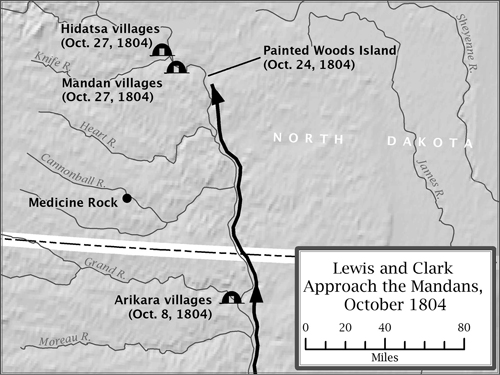

Figure 9.1. The Medicine Rock oracle stone, with a medicine wheel in the foreground. The stone, overlooking the Cannonball River (not the Heart River, as William Clark incorrectly believed), is still used by North Dakota’s native peoples.

Did the Indians also visit the stone in the spring of 1804, as Lewis and Clark set out from St. Louis? It seems likely that they did, but we can only imagine what it told them.

PAINTED WOODS, NORTH DAKOTA, OCTOBER 24, 1804

Prophesies aside, Mandan hunting parties spotted the expedition on October 23 if not before.5 The information networks of the plains may also have spread advance notice of the strangers inching upstream past the Cannonball and Heart rivers. On October 24, the Mandans encountered the visitors face-to-face.

The meeting took place on a large island in the Painted Woods, not far from the first towns the Mandans had built and abandoned after the smallpox of 1781. Several Mandan chiefs and their families were hunting on the island—possibly in anticipation of the expedition’s arrival—when the Corps of Discovery landed. The Indian leaders approached and gave the newcomers and their Arikara fellow traveler a very cordial greeting, Clark reported, and they all “Smoked together.”6

Having pushed upstream for more than a thousand miles—indeed many more, allowing for the river’s circuitous twists and turns—the strangers had a clear sense of the Missouri waterway. The island where they met the Mandans confirmed the river’s awesome power. Eight years earlier, when John Evans wintered among the villagers, an oxbow bend had looped around this same spot of land. It became an island soon thereafter. Landing there in 1804, William Clark deemed it “a butifull Country.”7 His appraisal still rings true today, though the hardworking river has wrought further changes over the years, filling in the ends of the oxbow, merging the island with the Missouri’s east bank, and creating lovely Painted Woods Lake to mark the old streambed.

MITUTANKA, OCTOBER 27, 1804

The company that proceeded upstream and landed at Sheheke’s west-side town of Mitutanka on October 27 was the largest party of non-Indians the Mandans had ever seen. With some three dozen members, the Corps at this point was a far cry from the “ten or twelve chosen men” that President Jefferson had first envisioned in his proposal to Congress. But from the point of view of the Mandans, accustomed as they were to the annual visits of enormous bands of trading Indians, this was still a small group of men, and the villagers could only assume that they too had come to trade. Commerce was the reason most strangers came to their towns, and Lewis and Clark’s vessels appeared well laden—though also well armed.8 The problem, as the Mandans saw it, would be keeping the neighboring Hidatsas, just two miles upstream, from horning in on their good fortune.

To the Mandans’ dismay, they soon learned that the newcomers were intent on continuing upriver. The boats stopped briefly at Mitutanka and Ruptare and then kept going as “great numbers” of Indians flocked to the riverbanks to watch their progress. The vessels eventually stopped and set up camp directly across from the Hidatsa villages. Here, Clark reported, many Indian men came across the river “to view us”; some brought their wives as well.9 Clark and Lewis called a grand council of all the Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs for the next day—Sunday, October 28. But when stiff winds kept Sheheke and other Mitutanka headmen from crossing the river, they delayed the meeting.

In the meantime, the Indians sized up the visitors, and the visitors sized up the Indians. Black Cat, a Mandan chief from Ruptare, spent hours with the captains, advising them about the leading men of each town. Several chiefs asked to see the keelboat, “which was verry Curious to them,” Clark said. Women brought gifts of corn and boiled hominy, and Captain Clark gave Black Cat’s wife a glazed earthen jar that she received “with much pleasure.” The day’s interactions seemed to please the explorers. “Our men verry Chearfull this evening,” Clark wrote.10 Sensing opportunities in the making, the Mandans may have felt the same way.

CORPS OF DISCOVERY CAMPSITE, OCTOBER 29, 1804

Two days later, the expedition captains tried again to have a council, but attendance was spotty once more. Local headmen seemed to do as they pleased, heedless of the captains’ summons. Sheheke and another leader from Mitutanka were gone hunting, as was a Hidatsa chief, while another Hidatsa headman was off on a raid against the Shoshones.

The impatient newcomers proceeded with their convocation anyway. An awning and a windbreak of sailcloth protected the dignitaries from the breeze. The council opened with a formal statement from the cocaptains, delivered by Lewis and translated by René Jusseaume. What we know of the text of this speech comes from Clark, who cryptically described it as “a long Speach Similar to what had been Said to the nations below.”11 But a speech Lewis delivered to the Oto and Missouri peoples in August gives us clues about what he might have said here.

France, Spain, and the United States had held a “great council,” he explained, and had decided that the “great chief” of the United States would henceforth be the Indians’ “only father.” The “old fathers the french and Spaniards” had already “gone beyond the great lake towards the rising Sun,” never to return again.12 The Corps, Lewis said, had come “to clear the road, remove every obstruction, and to make it the road of peace.” The Indians should “live in peace with all the white men, for they are his children.” And they should stop fighting among themselves as well. “The red men your neighbours,” Lewis said, were also the children of the “great chief,” who was “bound to protect” all of them. For the Mandans and Hidatsas, this meant peace with the Arikaras—which explained the presence of Toone, the Arikara chief who had come upstream with the expedition.13

If the Indians opened their ears and heeded their new father’s advice, Lewis said, he would send traders and merchandise up the Missouri River “annually in a regular manner, and in such quantities as will be equal to your necessities.” The Indians would be able to buy goods “on much better terms than you have ever received them heretofore.”14 This future trade would be ample, but he and his men were not traders themselves. They were “on a long journey to the head of the Missouri,” he said, which was why their boats bore provisions, not trade goods. They had few presents for any nation. But they did have several items—flags, medals, and military uniforms—to bestow on selected headmen. Perhaps one or more of them could even visit the U.S. president in Washington, D.C.15

As the speech and translation droned on, an old Hidatsa chief named Caltarcota, or Cherry Grows on a Bush, got restless and nearly left, either because he did not like what he was hearing or because Lewis was going on so long. When he wound down, Lewis and Clark together turned to Toone. It was time, they said, for the Arikaras to make peace with the Mandans and Hidatsas. The Indians present no doubt realized that the long-term likelihood of this was slim, but the men, including Toone, all smoked together anyway.16

Next Lewis and Clark conducted a ceremony they had performed several times among the nations downstream, building on the time-honored European tradition of designating preferred leaders among native peoples. It was a tactic that future generations of colonizers and expansionists were to perpetuate, and for Mandans and Hidatsas, it was one that also paid heed to local, honorific gift-giving traditions. There can be no doubt that all the parties involved viewed it differently. The captains called the procedure “making chiefs.” “The following Chiefs were made in Councel to day,” Clark wrote in his journal, compiling a list of Mandan and Hidatsa names that included Sheheke and Little Crow from Mitutanka—even though they were not present—and Black Cat and Raven Man Chief from Ruptare. With “much Seremony,” the explorers appointed one leader from each village to be “first chief” and gave these men “Coats hats & flags” and medals. The appointed “second chiefs” from each village also got medals. Lastly, the captains appointed Black Cat the “grand chief” of the Mandans.17

In this personal appointment of chiefs, Lewis and Clark were trying to create a mechanism for transmitting U.S. authority and policy to the Mandan and Hidatsa peoples. They seem to have believed they could remake village politics in a single gesture.18 Of course the Indians welcomed the presents, but from their point of view the chief-making ceremony did nothing to alter actual leadership anywhere. Bundle ownership and personal qualities, not outsider proclamations, determined the civil and war chiefs for each town, and holders of both offices needed the support of village elders to retain their stature.19

RUPTARE (BLACK CAT’S VILLAGE), OCTOBER 31, 1804

Two days after the council, Black Cat followed up with William Clark. In a gesture of generosity, friendship, and esteem, the Ruptare chief threw a decorated robe over the redheaded Virginian’s shoulders. Then the two sat with several old men and smoked silently in Black Cat’s lodge; eventually, Black Cat offered his response to Lewis’s speech.20

Peace with the Arikaras would be fine, he said. In fact, the Mandans wanted “peace with all” so they “Could hunt without fear, & ther womin Could work in the fields without looking everry moment for the Enemy.” To make good his intentions, the chief said he would send a company of “brave men” to escort the Arikara chief Toone back “to his village & nation, to Smoke with that people.”21 These reassurances pleased the expedition captains; as Clark saw it, the grand chief they had appointed was on board, and peace was at hand. Soon United States traders might open a prosperous commerce with the upper Missouri River’s allied villagers—Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa alike.

Clark, like his older brother, George Rogers Clark, had ample experience with Native Americans. But he did not comprehend plains diplomacy. He failed to recognize the tit-for-tat nature of tribal altercations and the farmer-nomad vacillation between trading and raiding, amity and discord. And he missed the subtext of what Black Cat said next. The Mandans were not the aggressors, Black Cat continued, and did not “make war on any without Cause.” But if attacked, they would not hesitate to defend themselves or exact revenge.22

Sheheke, the White Coyote, weighed in the next day, speaking for the residents of Mitutanka. “Is it Certain,” he asked, that the Arikaras “intend to make good” with us? The Mandans had recently sent “a Chief and a pipe” to the Arikaras “to smoke” and settle matters, but the Arikaras had murdered the emissary, he claimed. “We do not begin the war,” he asserted; “they allway[s] begin.” And once the fighting started, the Mandans killed Arikaras “like the birds.” Reconciliation would be fine. Indeed, the two tribes would “make a good peace.” But Sheheke’s reservations were clear. Mandan-Arikara violence dated back to the ancestral migrations of the 1300s. He knew the captains’ peace would not last.23

On November 6, Toone set out for home along with five members of the Corps of Discovery who were returning downstream instead of continuing on to the Pacific. If William Clark’s records are correct, Black Cat’s Mandan escort of “brave men” never materialized.24

It took only a few weeks for the concord—if it ever existed—to unravel. In late November, the Mitutanka villagers sent a boy across the river to tell Lewis and Clark the news: A “large party” of Sioux and Arikara warriors had surprised some Mandans out hunting. The attackers had stolen nine horses, wounded two hunters, and killed “a young Chief.” (Three months later, though, talk again turned to peace. In late February, two Arikara messengers came to the Mandans and Hidatsas with a proposal to cease hostilities and join forces against the Sioux. They even requested permission to again “Settle near” the Knife River towns. But when the Corps of Discovery passed through the region on their return trip a year and a half later, Mandan-Arikara hostilities were recurring.)25

FORT MANDAN, NOVEMBER 3, 1804

In early November, the most pressing problem Sheheke and others confronted was not long-term peace proposals but where the visitors would spend the winter. Sheheke watched with concern while the men of the Corps probed upstream and down for a suitable location to build cabins and a stockade. The chief even paid the captains a visit, pressing them to eschew Hidatsa territory upstream and to instead choose a downriver site close to his own people. “We were Sorry when we heard of your going up,” he said, “but now [that] you are going down, we are glad.” In the end, the Corps stayed among the Mandans, naming their little east-bank garrison Fort Mandan after their hosts. Sheheke promised the hospitality for which the villagers were famous. “If we eat you Shall eat,” he told the captains, reminding them gently that they would be dependent on the Indians: “if we Starve you must Starve also.”26

With the explorers close-by, the Mandans could monopolize their trade in the coming season, squeezing out the Hidatsas. Despite Lewis’s labored explanation at the grand council, the villagers still had not fully understood that the visitors were intent on “discovery,” not commerce. For the Mandan people, who knew exactly where they were and who made buying and selling the center of their existence, the whole proposition was absurd.

FORT MANDAN, NOVEMBER 4, 1804

The construction of Fort Mandan got under way quickly. This enterprise—probably supervised by the carpenter Patrick Gass—brought constant interaction with local residents. On November 4, the Canadian-born Toussaint Charbonneau came to see the building in progress. Charbonneau had lived among the Hidatsas for several years, claimed fluency in the Hidatsa language, and “wished to hire as an interpreter” for the journey upstream. The captains agreed.27

Charbonneau’s Hidatsa translations would be handy, but he came with additional assets. The captains anticipated encountering the Shoshone people when they crossed the Rocky Mountains. They hoped to buy food, purchase horses, and obtain directions from them, and for these purposes, they needed a Shoshone translator. The discovery that Charbonneau had not one but two Shoshone wives immediately piqued their interest.

The presence of Sakakawea and Otter Woman in the Knife River villages was testimony to a long-established traffic in human beings—a slave trade—that flowed along the same routes that carried foodstuffs, horses, and other items. This human commerce predated the natives’ contacts with Europeans and intertwined closely with patterns of war. But violence and the slave trade had both been increasing ever since the seventeenth century, when the cry for labor in distant colonial settlements grew louder and when epidemics, horses, guns, and strategic concerns stimulated new modes of interaction.28 European demand expanded the market, and epidemics left Indian families with empty spaces that adopted captives—especially children and women—could fill. Horses made long-distance raiding for slaves possible and appealing. Guns escalated the frequency of raiding and conferred advantages on those who had them. And strategic concerns led various Indian peoples to use slave raids as a wedge to keep enemies from establishing their own alliances with Europeans.29

As early as 1688, the baron Lahontan had used the help of six Essanape slaves—possibly Mandans—in opening relations with their nation. But most of the early written allusions to the northern plains slave trade came from eyewitnesses on the periphery of the Mandan world. In most instances, the farmer-villagers in these early reports were not the captors or brokers of slaves but slaves themselves, prisoners seized in intertribal warfare. The Frenchman Nicolas Jérémie appears to have interviewed such captives, Mandan or Hidatsa, among the Crees and Assiniboines who traded at Hudson Bay from 1697 to 1714. A French priest baptized an Arikara slave in Quebec in 1710. And Pierre de la Vérendrye’s partner La Jemeraye purchased “several” Mandan or Hidatsa children from the Crees and Assiniboines in the early 1730s.30

By the late eighteenth century, as written descriptions of the upper Missouri began to proliferate, we get glimpses of the human commerce that funneled through the villages—commonplace for generations but now growing with the demand for slaves in colonial settlements. Visitors reported that Mandans and Hidatsas purchased many captives from trading peoples who brought them in for sale. In 1806, the North West Company trader Alexander Henry saw a band of Crow Indians bring “great numbers of horses, some skins and Furs and Slaves to barter” at the Knife River towns. The Crows received “guns Ammunition, Tobacco, Axes &c.” in return.31

In other instances, the Mandans and Hidatsas took to the warpath themselves, launching raids that chastened enemies, enhanced warrior prestige, and built wealth in the form of captured horses and slaves that could be bestowed as gifts or sold in the village marketplace. In January 1798, when David Thompson and his companions returned from their terrible, storm-plagued trip to Mitutanka and came back to the Assiniboine River, their entourage included two slaves—“Sieux Indian women which the Mandanes had taken prisoners, and sold to the men, who, when [they] arrived at the Trading House would sell them to some other Canadians.” Hudson’s Bay Company traders visiting the Mandans four years later witnessed the return of a war party from Shoshone country (the villagers’ “war Path” west appears on one of Clark’s maps) bringing “150 horses & 8 Slaves from the Snake Inds.”32

It could have been this very raid that brought Charbonneau’s two Shoshone wives—Sakakawea and Otter Woman—to the Knife River villages. We know the most about Sakakawea because she traveled with Lewis and Clark, appeared in their journals, and became the subject of much historical scrutiny. She rose to fame with the publication in 1902 of a novel about Lewis and Clark by the American suffragist Eva Emory Dye. Ever since, Sakakawea has been a famous member of the Corps of Discovery, commemorated in statues and on coins, and admired and debated in biographies, articles, and public forums.33

By most estimates Sakakawea was born around 1788 and fell into the hands of a Hidatsa war party when she was between ten and twelve years old. Her capture occurred while she camped with her people near Three Forks, the place in what is now southwestern Montana where the Madison, Gallatin, and Jefferson rivers merge to form the Missouri. The Corps of Discovery spent three days at this “prosise Spot” in July 1805. As Meriwether Lewis learned, the Hidatsas ambushed the Shoshones there, “killed 4 men 4 women a number of boys, and mad[e] prisoners of all the females and four boys, Sah-cah-gar-we-ah o[u]r Indian woman was one of the female prisoners taken at that time.”34

Some of Sakakawea’s companions escaped, but the Hidatsas took her, Otter Woman, and another prisoner named Leaping Fish Woman to the Knife River villages. Here Sakakawea and Otter Woman lived with the family of their captor, Red Arrow, who soon bought Leaping Fish Woman too. The arrangement did not last. Leaping Fish Woman made her escape after a year in captivity, and Red Arrow lost Sakakawea and Otter Woman in an all-night gambling match with Toussaint Charbonneau.35

At Fort Mandan, the expedition captains spent hours with these two women, talking, according to Sakakawea, “about our country … [they] got us to make pictures of it and show them where we thought they would be likely to meet our Snake [Shoshone] people.” Sakakawea delivered a son, Jean Baptiste, two months before the Corps of Discovery left for points westward. The young mother was probably around sixteen, as was Otter Woman. But Otter Woman was not so lucky. She was pregnant when the expedition departed, and Clark refused to let her make the journey.36

Thus it was that Sakakawea found herself, baby in tow, once again at Three Forks, where the Hidatsas had captured her five years earlier. We might imagine the thoughts that ran through her mind, but Lewis found her inscrutable. “I cannot discover that she shews any immotion of sorrow in recollecting this events, or of joy in being again restored to her native country,” he wrote.37

Three weeks later, when the expedition encountered a band of Shoshones that included Sakakawea’s brother Cameahwait, she was easier to read. Spotting the Shoshones in the distance, she and Charbonneau “danced for the joyful Sight,” Clark reported. Lewis too was moved. “The meeting of those people was really affecting,” he wrote. So profuse were Sakakawea’s tears that the captains postponed their council with Shoshone leaders until she could compose herself. Cameahwait was not the only person she was happy to see. She was equally thrilled about a Shoshone woman “taken prisoner at the same time with her” who had fled “and rejoined her nation.” Leaping Fish Woman had made it home.38

As the stories of Sakakawea and Leaping Fish Woman suggest, the fates of Mandan and Hidatsa captives varied. Captive children were often incorporated into existing families and thus may have had the easiest time. A Ruptare Mandan named the Coal, who visited Lewis and Clark often, was an adopted Arikara, and a Mitutanka headman named Big Man was an adopted Cheyenne. Their kin ties facilitated commerce with the Arikaras and Cheyennes, and villagers encouraged “strangers” of all backgrounds to live among them for this reason.39

Other outcomes of captivity are harder to characterize. Some enslaved Indians, such as the Sioux women who traveled with David Thompson in 1798, faced sequential owners and probably forced marriages and other forms of abuse. If such women married Mandan men, they garnered some benefits of kinship, but they may have had lower status than other wives, with no claim to gardens, earth lodges, or clan property.40

Redemption was another outcome, though it is impossible to say how often it occurred. The fur trader Charles McKenzie reported that in the fall of 1804, a Hidatsa war party captured a woman and two children of Flathead or Shoshone origin. The woman’s husband, away hunting when the attack occurred, “immediately formed the bold and desperate resolution of pursuing the enemy in hopes of an opportunity for retrieving his loss.” He trailed the war party all the way to the Knife River villages but found no chance to liberate his family.41 Distraught, he climbed a hill beside the town in which his wife and children awaited their fates. Alone and unarmed, “he boldly made his appearance, singing his Death Song.” When the alarmed villagers approached him, he told them there was “no danger.” And he continued: “I came for my wife and my Children whom your young men have carried away captives— If they are your Slaves, make me also your Slave;— if they are not among you, and are no more, let me go with them to the land of Spirits. Here, Enasas [Hidatsas], dispatch me! I cannot live! I am your Enemy.”42

The man’s plea unleashed a wave of emotion from the Hidatsas. They invited him into their town, gave him his wife and children, and beseeched him to stay “as long as he pleased.” He chose not to linger. But the next summer he returned with a party of Crow traders and presented the Hidatsas with “six famous horses and a great quantity of dressed leather.” McKenzie believed the episode pointed to the possibility of “an amicable and lasting intercourse” between the villagers and the Flatheads and Shoshones in the future.43

Other captives—like Leaping Fish Woman—took it upon themselves to escape. One Shoshone woman was captured on three separate occasions, returning to her people twice. The third time, she took “a fine horse” and “two knives” with her when she ran away, a theft that infuriated her villager captors. A group of young men pursued the woman, tracking her route by the holes in the earth where she stopped to dig prairie turnips. Before long they came back “with her head at the end of a pole.” The men of the town ignored it, considering “the head or Scalp of a woman beneath their notice.” But the women were “overjoyed at the Spectacle” and kicked the head about the village, shouting, “There is the Enemy! Take care! Be kind to her!” Finally, boys took the head and used it “as a mark to exercise their arrows.”44

The Hidatsa man who had captured the unlucky Shoshone woman told Charles McKenzie she was “very pretty” and that he was sure “the white men” would have given “a generous price to us for her.”45

BIG HIDATSA WINTER CAMP, NOVEMBER 25, 1804

By November 25, the men of the Corps of Discovery had spent more than a month at the Knife River villages. But the Hidatsa chief Horned Weasel wanted nothing to do with them. Like several other leading Hidatsas, he had missed the grand council in late October, and since then, the Corps had made barely a gesture toward the Hidatsa people. As they saw it, the captains had made their partiality clear by building their winter quarters below the Mandan villages and cultivating their Mandan neighbors exclusively.46

If that was what the strangers wanted, so be it. The Hidatsas remembered John Evans and his unfulfilled promises of a prosperous trade from Spanish St. Louis. Lewis and Clark’s proffer of a similar commerce with U.S. operators was likely a fantasy as well. Besides, the Hidatsas had their own geographic and commercial advantages. They occupied the northernmost towns along the Knife River, and British traders crossing the plains from the Assiniboine River posts reached their villages first; they had close ties to these men.

Since Lewis and Clark seemed determined to ignore them, the Hidatsas relied on the Mandans for information. What they told them, according to William Clark, was this: The Corps of Discovery “intended to join the Seaux to Cut off” the Hidatsas “in the Course of the winter.” Some Hidatsas may have suspected this was Mandan rumor-mongering, intended to keep the more northerly villagers at a distance, but others saw evidence that the story might be true. Why else would “interpreters & their families”—people like Toussaint Charbonneau and Sakakawea—have left the Hidatsa villages and taken shelter at Fort Mandan? And what else could explain the imposing nature of the fort itself?47

For all these reasons, when Meriwether Lewis finally made the short trip upstream to the Hidatsas on November 25, Horned Weasel had no truck with him and refused to play the friendly host. When he learned that Lewis was intending to stay at his lodge, he sent a message that he “did not Chuse to be Seen by the Capt. & left word that he was not at home.”48 The cold reception dismayed Lewis, since hospitality was a defining attribute of Mandans and Hidatsas alike. “This conduct surprised me,” he told a British fur trader, “it being common only among your English Lords not to be at home, when they did not wish to see strangers.”49 But English lords had no lock on the diplomatic snub. Feeling insulted himself, Horned Weasel had responded in kind.

ON THE NORTH DAKOTA PRAIRIE, NEAR THE SITE OF MITUTANKA

The pattern is barely perceptible on the ground. But from the air, when the shadows grow long, you can see it: a series of shallow, linear trenches, roughly parallel, running north-south across the plains. These trenches are marks in a field, now cultivated, eight miles northwest of the Leland Olds Power Station, formerly the site of Mitutanka. The plow and the wind have diminished their visibility, but the little gullies track southward from the field for another mile or so until they run into the Knife River itself. The Knife is a modest waterway; indeed, you can toss a rock from one side to the other. But it does flow year-round, and if you follow its meandering loops downstream, you soon come to the remains of the Knife River villages.

For decades, the linear depressions in the grass left geologists baffled. Similar channels, usually trending northwest to southeast, can be found elsewhere on the northern prairies—in Alberta, Manitoba, Montana, Minnesota, Wyoming, and both Dakotas. Some experts believed these strange lines indicated seams or faults in the underlying bedrock. Others, including a geologist named Lee Clayton, thought the trenches were ancient crevasses, once filled with glacial ice but now filled with debris.50

For a scientist like Clayton, working in North Dakota, this theory made sense. Glaciers had indeed covered most of the state six hundred thousand years ago. Clayton stuck with this hypothesis for nearly two decades, but then, in 1970, he found similar gullies in the southwestern corner of the state, which happens to be the only portion of North Dakota untouched by Pleistocene glaciation.51 Since glacial ice had not existed there, the crevasse theory could not explain the distinctive trenches. Something else had created them. But what?

The answer was bison. For thousands and thousands of years, millions of American bison had ranged over the plains, sometimes thundering in herds, sometimes lumbering single file. What drew them to the Knife River was water. Enticed by its wafting scent, the beasts followed their noses into the wind. Year in and year out, they used the same trails. They walked straight over low-lying hillocks and the snakelike eskers left by glaciers, deviating from their wind- and water-determined path only when confronted by more difficult obstacles. In these locations the gullies turn briefly, where the bison that created them once did, until the terrain flattens and the scent-bearing breeze beckons again. Maximilian, steaming up the Missouri River in the very same area in 1833, had marveled at the way bison had altered the landscape. “Everywhere in the nearby prairie,” he remarked, “were fresh and deeply trodden buffalo trails.”52

Lee Clayton confirmed his new theory by watching cattle on the move. He noted the way dirt stuck to their hooves, the shape of the paths they created, and their tendency to head toward water. Today, few bison survive, but their ancient presence still marks the landscape. Geologists have noted that many tributary prairie streams run parallel to the prevailing winds. Clayton thinks these too might have begun as bison trails, which then, enhanced by erosion, became streambeds in their own right, carrying life-giving water into the larger streams and rivers that cut across the continent.53

MITUTANKA, JANUARY—MOON “OF THE SEVEN COLD DAYS”—180554

Mere miles from Lee Clayton’s bison-trail trenches, the Mitutanka Mandans made their own efforts in early January 1805 to draw the plains behemoths near. For two nights they danced. On the third night, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark sent a man across the river to attend the proceedings. It was he who probably told Clark about the ceremony in which he had participated.

Clark described the proceedings in his diary. It was “a Buffalow Dance”—the same ceremony that George Catlin was later to join on the fourth day of the Okipa he attended. This, however, was a slightly different version, in which the Buffalo Bulls sat in a circle and the young men approached them, beseeching them to have intercourse with their wives. The wives too presented themselves, “necked except a robe.” Not all requests were honored, much to the husbands’ chagrin. But when an old bull did accept, he and his partner left the lodge for “a Convenient place for the business.” Business done, they returned.55

William Clark was accustomed to easy sexual relations between Corps members and their Indian hosts. His men had enjoyed the comparative license of Arikara women as they made their way upstream, and he recorded the details of the January ceremony with bemused indifference. “We Sent a man to this Medisan Dance last night, they gave him 4 Girls,” he wrote; “all this is to cause the buffalow to Come near So that They may kill thim.”56

Clark’s contemporaries back east did not share his comfort with these interactions. Nicholas Biddle, the well-educated Philadelphia diplomat and financier who was the first to edit the Lewis and Clark journals and see them to publication, altered many passages along the way. His changes highlighted a nationalist narrative and made the captains’ language more accessible to readers. But he drew a sharp line at the Walking with the Buffaloes description. Here, instead of clarifying Clark’s prose, he rendered it in Latin: “Effigium solo et superincumbens, senili ardore veneris complexit,” he began, convinced that only the well educated should have access to such material.57

On January 9, just days after the unnamed Corps member’s spirited participation in the buffalo-calling ceremony, bison did indeed appear near Mitutanka. The ceremony, apparently, had worked. “This early success the Mandanes attributed to the captains’ people, who were untiringly zealous in attracting the cow,” wrote the fur trader Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, who had not himself been present but who had witnessed the explorers’ encounter with the Arikara women and thus had some basis for his appraisal. What Euro-Americans perceived as sexual freedom—and what Mandans perceived as the transfer of xo´pini—was part of the attraction of the Missouri River villages. In 1797–98, on his brutally cold trip, David Thompson had been dismayed to find that the “almost total want of chastity” of Mandan women was well known to his men and was “almost their sole motive for their journey hereto.”58

After the bison came in, William Clark watched for four days as “about ½ the Mandan nation passed” by the fort to hunt the animals “on the river below.” Then on January 14 he sent six men to join them. He did so with reservations. “Several men,” he said, were down with “the Venereal cought from the Mandan women.” For all his frankness about frontier sexuality, Clark seemed oblivious to the role his own men may have played in spreading infection.59

KNIFE RIVER VILLAGES, NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 1804

As fall turned to winter, the Mandans tried to fathom the strange men in their midst. Their numbers, demeanor, and deeds distinguished them from the French and British traders who preceded them. Lewis’s speech had invoked the new “great father” of America and had promised plausible things—friendship, happiness, commerce, and abundance—but the actions of the Corps did not bear them out. The villagers thought their guests were stingy. To come with amply loaded boats but tell them they “brought but very few goods as presents” was a flagrant breach of plains protocol. Where was the evidence of the new great father’s love and affection?60

Just two days after the council and speech, Black Cat told the captains of his dismay. The Mandans “expected Great presents,” he said, but “they were disappointed, and Some dissatisfied.” The Indians also complained to the British trader Charles McKenzie, who recorded their words. “Had these Whites come amongst us … with charitable views they would have loaded their Great Boat with necessaries,” they said. The effort to impress and entertain them by firing their air gun was especially annoying. “It is true they have ammunition,” the Indians said, “but they prefer throwing it away idly than sparing a shot of it to a poor Mandane.”61

In November, Black Cat told Lewis and Clark how, a few years earlier, John Evans had also come from the south, wintering among the villagers and talking of great things. He had “promised to return & furnish them with guns & ammunition,” but nothing had materialized. “Mr. Evins had deceived them,” Black Cat told the captains, “& we might also.” It all seemed familiar. The Mandans, after meeting in council to discuss the matter, said they would continue to welcome northern traders from Canada “untill they were Convinced” there was truth in Lewis’s words.62

They also continued their gracious hospitality. Mandan women brought gifts of corn to the explorers almost daily. As Sheheke had intimated, the men of the Corps needed Indian produce to survive. But they had only a paltry supply of merchandise to give in return. The imbalance of reciprocity, expressed in gifts or explicit trade, could not last. Then, in the closing days of 1804, an unexpected solution emerged. On December 27, a windy day with fine snow, the carpenter Patrick Gass and the men at Fort Mandan put the last touches on a smithy they had built beside the post. The expedition blacksmith, John Shields, could now get to work. The men fired up the forge, and the Indians watched with fascination, “much Surprised at the Bellos & method of makeing Sundery articles of Iron.”63

Metal trade goods had reached the Mandans two centuries earlier, around 1600. By the mid-1700s, thanks to the Crees and Assiniboines, the villagers had a regular supply of metal knives, hatchets, axes, kettles, and hoes. And now they also had a growing number of items that needed repair. With a forge in their midst, Indians flocked to exchange foodstuffs for blacksmith work. “A Number of indians here every Day,” wrote Clark on December 31. “Our blckSmitth mending their axes hoes &c. &c. for which the Squars bring Corn for payment.”64 Corn flowed steadily into Fort Mandan, along with broken axes, hoes, bridles, and other metal items.

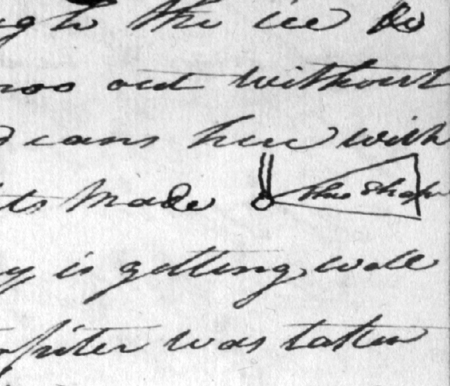

Figure 9.2. A Mandan war hatchet, drawn by William Clark, January 28, 1805.

Then, within a month, something changed. A new item took shape on John Shields’s anvil: “The blacksmith makes war-axes, and other axes to cut wood; which are exchanged with the natives for corn,” Gass wrote on January 26. Two days later, William Clark mentioned “Several Indians here wishing to get war hatchets made.” In their journals, the captains each drew sketches of these varied and coveted items. War hatchets probably had ornamental and ceremonial uses, but they were mostly for battle. The Mandans and Hidatsas were crazy for them, and they were unabashed about their use: “A war Chief of the Me ne tar ras [Hidatsas] Came with Some Corn,” wrote William Clark on February 1. The man “requested to have a War hatchet made, & requested to be allowed to go to war against the Souis & Ricarres who had Killed a mandan Some time past.” The captains would not assent to his plans, though the chief probably got his hatchet anyway.65

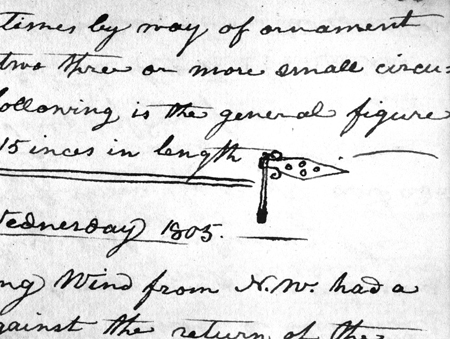

Figure 9.3. A Mandan battle ax, drawn by Meriwether Lewis, February 5, 1805. This ax is obviously different from the one drawn by Clark. Clark found the design of such axes to be “very inconvenient.” The Mandans used different axes for different purposes, and it is conceivable that this one was ornamental or ceremonial.

This demand for tomahawks, which so obviously flew in the face of the captains’ high-minded talk of peace among the peoples of the Missouri, suggests how little stock the Indians put in that talk, even if they paid lip service to it.66 Plains diplomacy was fluid and changeable. Today’s trading partners could be tomorrow’s enemies, and so far the Corps of Discovery had given the villagers little reason to undertake a dramatic, almost inconceivable change on its behalf. And the explorers, undermining their own stated goals, had little choice, since the weapons, as Clark observed, were “the only means by which we procure Corn.” In his view, the war-hatchet trade was a necessary evil. The Mandans, however, were delighted. “There are only two sensible men among them,” the Indians told Charles McKenzie: “the worker of Iron, and the mender of Guns.”67

So the commerce continued, escalating in March as the expedition’s departure drew near and the Mandans realized that the blacksmith would be leaving. “The Savages continue to visit us in Order to git their impliments of War made,” wrote John Ordway on March 2. “Maney Inds. here to day all anxiety for war axes,” added Clark on March 13. “The Smiths have not an hour of Idle time to Spear.”68

Figure 9.4. Mato-Tope Adorned with the Insignia of His Warlike Deeds, hand-colored aquatint print (after Karl Bodmer), 1834. The Mandan chief Mato-Topé, or Four Bears, holds a classic Missouri River war hatchet.

On April 7, 1805, the members of the Corps of Discovery left Fort Mandan to continue their journey west. Sakakawea, Charbonneau, and their baby, Jean Baptiste, accompanied them. The party reached the Pacific seven months later and spent the next winter at Fort Clatsop, near the mouth of the Columbia River. On their homeward-bound trip, when they were spending a night with a Pahmap Nez Perce band in early May 1806 in what is now northern Idaho, at a campsite on the west side of the Rocky Mountains, John Ordway happened to see something that astonished him. The Nez Perces were enjoying a gambling game (he had seen other peoples play it too), and the bettors sat with their stakes piled next to them. Among the items in play were war hatchets made by John Shields during the Fort Mandan winter: The Nez Perces had purchased them from Hidatsas, Ordway learned, who “got them from us at the Mandans.”69

BIG HIDATSA, KNIFE RIVER, JULY 21, 1806

More than a year after the Corps of Discovery left for the Pacific, the dour Nor’Wester Alexander Henry visited the Knife River settlements. He arrived at the town called Big Hidatsa amid a pack of village dogs so annoying that he brandished a club to keep them at bay. If the Jeffersonian adventurers had altered village life, it was hard to see how.

The Hidatsas professed little fondness for the departed expedition. According to Henry, “they were all much disgusted at the high sounding language” the visitors had used. The captains had tried “to impress the Indians with an Idea of their great power as Warriors,” but the Hidatsas found their “manner of proceeding” offensive. Lewis and Clark’s medals and flags were gone. “Those ornaments had conveyed bad Medicine to them and their children,” the Hidatsas said. They thus used them to good effect by giving them to their enemies “in hopes the ill luck would be conveyed to them.”70

The Mandans had sustained better relations with the Corps, and the medals and flags from the chief-making exercise could still be found among them. But they had dismantled a steel grain mill Clark had given them at the big council of October 1804. Wooden mortars and pestles worked fine for pounding maize. The Mandans needed weapons. So they broke apart the mill “to barb their arrows, and other similar uses,” Henry said. One remaining piece of steel from the mill was too thick to rework. It served the women nicely “to pound marrow bones to make grease.”71

MITUTANKA, FEBRUARY 20, 1805

A generation after the catastrophic smallpox of 1781, Lewis and Clark’s reception at the Knife River villages had been a testimony to Mandan resilience. The people seemed lively and prosperous, but their air of security and contentment masked a profound sense of loss. The captains had glimpsed the destitution and upheaval of the recent Mandan past when they traveled through the Heart River homeland, and they caught whispers of it when they listened to Sheheke speak of his youth. For the Mandans at the Knife River, all was not right.

During his months among the villagers, William Clark met a Mandan elder who said he “was 120 winters” in age.72 His name is lost to us, but if he was indeed 120, he would have been alive at the time of Lahontan’s early probes of the Missouri River. Even if he was not quite so old, he had borne witness to a whirlwind of historical change. It is no stretch to imagine that his life encompassed La Vérendrye’s visit, the coming of the horse, the smallpox of 1781, the migration north to the Knife River, and the influx of the non-Indian traders. His final earth lodge was in the village of Mitutanka.

On February 20, or perhaps the night before, this old man died. His last wishes reveal his longing for a bygone era: “he requested his grand Children to Dress him after Death & Set him on a Stone on a hill with his face towards his old Village or Down the river, that he might go Streight to his brother at their old village.”73

The heart of the world still drew him home.