Epilogue

ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1838

The epidemic of 1837–38 stands with the epidemic of 1781 as one of the greatest catastrophes ever to strike the peoples of the northern plains. It virtually destroyed the Mandans at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, and although those at Ruptare managed to hang on to their town after the pestilence, their numbers were few. Observers in later years counted anywhere from eight to twenty-one lodges. When Rudolph Kurz visited Ruptare in 1851, he found “fourteen huts, most of them empty.” The residents, he said, were a “poor remnant of a tribe.”1

Two things enabled Ruptare to survive: The inhabitants maintained good relations with the Arikaras nearby, and they cultivated ties with the Yankton Sioux. The mother of the Yankton chief Medicine Bear was a Ruptare Mandan, captured by the Sioux in the Painted Woods after the 1781 epidemic. The Sioux headman professed a firm connection to his Mandan cousins at Ruptare.2

The Nuitadi Mandans of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch never reoccupied their town after they left in September 1837. Some have called the period that followed the “lost years” of these Mandans.3 Like their forebears in 1781, they were refugees.

Over the winter of 1837–38, they made a camp upriver from their old village. Despair settled in. Two lost their lives in a December battle with some Assiniboines. In February, they visited Fort Clark for an uncharacteristic “drunken frolic.”4 (Mandans and Hidatsas had mostly avoided the use of alcohol before this. “Drunks, common [in] the more northern nations, hardly occur here,” Maximilian had noted.)5

On March 20, the Mandans could only watch as the more numerous Arikaras left their own winter camp below Fort Clark and trekked up the embankment to Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, the Mandans’ old town, now virtually empty. “Several Ree lodges arrived,” wrote Chardon; “the rest will be here to morrow—to take possession of the Mandan Village.”6 He did not note the Mandan reaction.

Ten months later, in the early morning hours of January 9, 1839, the shouting of Indians awakened Chardon. He walked outside Fort Clark and saw a shocking scene. The Sioux had attacked the Arikaras living at the old town. “I beheld the Mandan Village all in flames,” he wrote; “the Lodges being all made of dry Wood, and all on fire at the same time, Made a splendid sight.” The fur trader found meaning in the conflagration. “This Must be an end to What was once called the Mandan Village,” he said. “The Small Pox last year, very near annihilated the Whole tribe, and the Sioux has finished the Work of destruction by burning the Village.”7

Yet new earth lodges soon rose from the ashes. The Arikaras, most of whom were at their winter camp, returned in the spring and built the town over again.8

Remnants of the Nuitadi Mandans had meanwhile scattered and sought refuge wherever they could find it. A few had tried to live with the Arikaras at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch that spring, but they quarreled over their hosts’ treatment of Mandan women. By the end of June 1838, well before the Sioux attack and fire, they left to join the Hidatsas.9

Some of their kinfolk took up hunting and foraging, migrating west and southwest. Winter counts put Mandan survivors on the Yellowstone River in Montana during the winter of 1839. A count kept by a Mandan man named Foolish Woman says the Nuitadis split up for the season, one group camping on Rosebud Creek, below the Yellowstone’s confluence with the Bighorn, and the other staying lower down on the Yellowstone. Another count, kept by the Mandan named Butterfly, put a combined band of Mandan and Hidatsa refugees farther up the river, not far from present-day Bozeman. A Sioux winter count indicates that some Mandans also headed southwest; it marks 1845 with the designation “Mandans wintered in Black Hills.”10

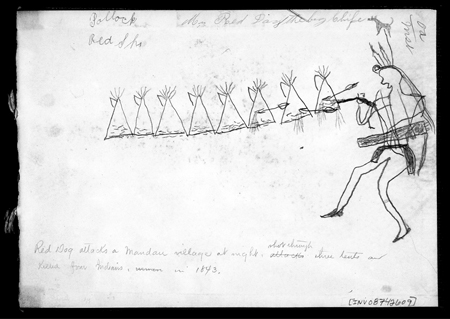

Mandan clashes with the Sioux and Assiniboines continued, on the Missouri as well as in the west. A Lakota ledger drawing from the 1880s portrays an attack on the Mandans in 1843. Four streams of blood flow from the Mandan tipis, indicating the four villagers killed in the battle. The tipis themselves suggest the itinerant life many Mandans had now taken up.11

Figure 15.1. Red Dog Attacks a Mandan Village at Night, Shot through Three Tents and Killed Four Indians, in 1843. This Lakota ledger drawing was probably made in 1880 by Red Dog to portray his attack on the Mandans in 1843. Mandans regularly used tipis on hunting excursions, but in this case the tipis may point to the villagers’ brief adoption of a hunting-and-foraging lifeway after the 1837–38 epidemic.

Even as they wandered, chasing bison, bear, and elk, the survivors clung fiercely to the traits that made them Mandan. According to a Canadian boy adopted into one of the itinerant bands, they even performed the Okipa. “They slit our backs and breasts with knives and passed thongs through under the skin and tied old buffalow heads to us,” he said. He may have been describing a version of the Okipa-related Sun Dance, but the Okipa itself is more likely. Its performance was consistent with the cultural conservatism—a determination to adhere to old ways—that Alfred Bowers observed among descendants of these survivors.12 The Mandans’ material world had unraveled, but their history and identity remained. The Okipa was their essence.

LIKE-A-FISHHOOK VILLAGE, SUMMER 1845

Most of the itinerant Mandans returned to the Missouri River in the summer of 1845. They came at the invitation of the remaining Hidatsas, who had also reorganized after the epidemic. Some had taken to the chase with their Crow kinfolk, but most apparently stayed on the river. Now they invited the Mandans to join them in building a consolidated village on the north side of the Missouri, where the river flows due east in its arcing trajectory, some thirty miles upstream from their former home. In times past, Mandan ancestors had adapted to moments of hardship and dislocation with similar acts of resettlement. The new town’s name was Like-a-Fishhook.

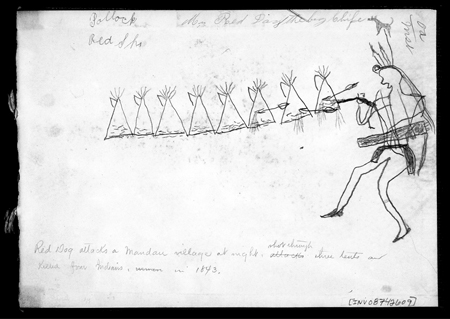

Figure 15.2. The Real Site of FishHook Village, 1834–1886, drawing by Martin Bears Arm.

The creation of Like-a-Fishhook was an act at once diplomatic, spiritual, and physical. The diplomacy involved not just Mandans and Hidatsas but also the American Fur Company, which built a new trading post named Fort Berthold beside the town. Spiritual concerns governed the selection of the site and the design of the settlement. Under the guidance of the esteemed Hidatsa leader Wolf-chief, the villagers drew upon the most powerful bundles and their holders to plan the town’s layout. And the Mandan and Hidatsa Black Mouths—charged with policing and defending village life—supervised its construction.13

The residents of Like-a-Fishhook did not just build earth lodges, palisades, and drying stages. They also established a ceremonial plaza. Since Hidatsa towns typically did not have such areas, the plaza at Like-a-Fishhook existed to fulfill Mandan spiritual needs. At its center stood the sacred cedar. And to one side was the Mandan ceremonial lodge, identifiable by its classic square front.14 Here, for the next forty years, descendants of the Heart River villagers reenacted their story, invoking Lone Man and affirming the ways and events that made them Mandan.

In 1857, after another bout of smallpox, Ruptare’s residents also moved to Like-a-Fishhook. Five years later, the Arikaras joined them. Henceforth, the three tribes made their lives together—an affiliation already made official in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851.15

Like-a-Fishhook was the last earth-lodge village on the upper Missouri River. Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras stayed there until the Bureau of Indian Affairs forced them to take up individual allotments in the 1880s. In 1887, a visitor found the Like-a-Fishhook Okipa lodge “roofless and ruined.” Just a few elderly Indians remained—mostly Mandans, including the Mandan chief Red Buffalo Cow (see figure 15.3) and his wife. “The Mandans,” said the Indian agent Abram Gifford, “are the last to relinquish the hold which tradition has given them to this place.”16

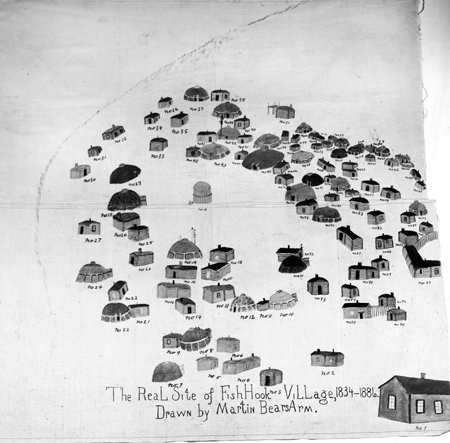

Figure 15.3. Red Buffalo Cow (a.k.a. Red Roan Cow or Red Cow) (right) and Bad Gun (a.k.a. Charging Eagle) (left), first and second chiefs of the Mandans. Photograph by Stanley J. Morrow on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation circa 1870. Bad Gun was the son of Four Bears and Brown Woman, both of whom died in the 1837–38 epidemic.

Mandans continued to perform the Okipa during the 1880s. Then the Ghost Dance and other ritual gatherings organized by various western Indians began to arouse anxieties among U.S. government officials. Bowers reports that the army officer in charge of Fort Berthold banned the Okipa ceremony “about 1890.” According to Mandan tradition, the last Okipa was in 1889.17

FORT STEVENSON, DAKOTA TERRITORY, 1869

In 1865, a U.S. army surgeon-ethnographer named Washington Matthews was posted to the Dakota Territory, serving at Forts Union, Berthold, and Stevenson over the next six years. The Irish-born physician was interested in all things Indian. He got to know the village peoples well, married a Hidatsa woman, and even wrote a Hidatsa ethnography. He also kept one of George Catlin’s tomes with him. When word spread among the villagers that Matthews “had a book containing the ‘faces of their fathers,’” the Indians flocked to his Fort Stevenson quarters. “The women,” he said, “rarely restrained their tears at the sight of these ancestral pictures.”18

Matthews at first thought the men had “less feeling and interest.” But he learned otherwise when he showed Catlin’s portrait of Four Bears to his son, a Mandan chief named Bad Gun. As a boy, Bad Gun had gone with his father to visit with Bodmer and Maximilian. He may have spent time with Catlin too. Now the son of the great chief “showed no emotion” but gazed “long and intently” at the image until Matthews left the room. When the doctor returned, the Mandan was “weeping and addressing an eloquent monologue to the picture of his departed father.” Three years later, the photographer Stanley J. Morrow made an image of Bad Gun himself.19 (See figure 15.3.)

MITUTANKA VILLAGE, JUNE—“MOON OF THE SERVICEBERRIES”—186220

Lewis Henry Morgan is sometimes called the “Father of American Anthropology.” He was a pioneering evolutionary theorist, anthropologist, and ethnographer. Although his specialty was the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, he cast his net broadly, collecting, visiting, and recording everything he could find pertaining to other Native American groups as well.

In the spring of 1862, Morgan traveled up the Missouri River in a steamboat named the Spread Eagle. The vessel, in the words of the historian John Ewers, became Morgan’s “traveling anthropological field station” as he collected artifacts, interviewed Indians and fur traders, and compiled assiduous field notes. On June 3, he reached the site of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch and Fort Clark. After the Sioux had torched the town in January 1839, the Arikaras had rebuilt it to their liking, but it appears that they did not give the settlement a distinctive name of their own. By the time of Morgan’s visit, the place was empty. Fort Clark had burned to the ground, and the Arikaras had left for Like-a-Fishhook just a few months before. The village stood silently on its bluff, still “conspicuous for some miles above and below.”21

While the steamboat crew collected wood from the timber of the abandoned town, Morgan wandered through the ruins. “Here for the first time,” he said, “I have seen the dirt houses of the Upper Missouri, and they far surpass my expectations.” Some lodges had collapsed, but others stood “just as they were left,” with willow mats and strings of dried corn still hanging inside. The anthropologist collected artifacts galore: stone mauls and hammers, an elk-horn skin dresser, a buffalo-horn spoon, an iron war hatchet, a wooden corn mortar, a ladder, and more.22

The ceremonial plaza drew Morgan’s attention as well. There he found the sacred Grandfather Stone and the red cedar Grandmother Tree of the Arikara people. “The rough bark had been removed and the top ornamented with strips of red flannel,” he observed. Mistaking the tree for the sacred cedar of the Mandans, Morgan uprooted it and carried it onto the Spread Eagle. The relic, he believed, bore “silent witness” to the Mandan Okipa. “If it could speak, it would unfold many singular ceremonies illustrative of the religious fervor … of this remarkable people.”23

ON-A-SLANT VILLAGE, JUNE 9–12, 2011

Lewis Henry Morgan was wrong about the cedar he stole from the Mih-tutta-hang-kusch site, but he was right about the “singular ceremonies” at the center of Mandan life. Informants told Alfred Bowers in the 1930s that the Okipa grew with the people themselves. Since the ceremony was so deeply historical, embodying “all things under the sun,” it had to change to stay true to its purpose.24 No two Okipas were exactly alike, and no two Okipa Makers had exactly the same visions. The point remains true, even in the early twenty-first century.

I write these words in the summer of 2011, almost a century and a half after Morgan visited the ruins of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. A hundred and twenty-two years have passed since the last-known Okipa. But the spiritual commitment of Cedric Red Feather, also known as the Red Feather Man, remains unabated. He is a Nueta Waxikena—a Mandan turtle priest. He is also a modern-day Okipa Maker.

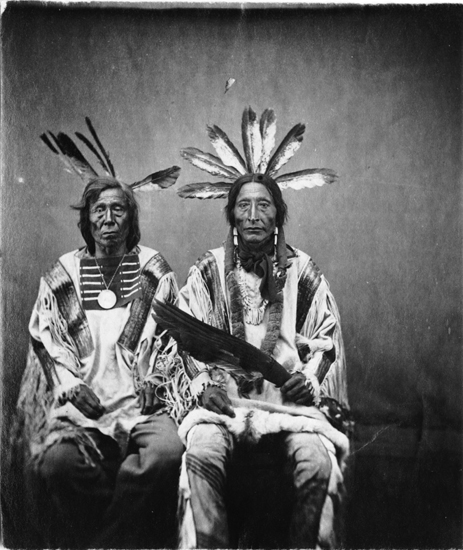

Figure 15.4. Cedric Red Feather, Mandan Okipa Maker, 2011.

The Red Feather Man’s great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather—Red Buffalo Cow (see figure 15.3) and Running Face (see figure 7.4)—might well have participated in the Okipa of 1889. Both were prominent ancestors on his father’s side. Cedric’s mother’s lineage goes back to Sheheke and On-a-Slant Village. His great-grandmother, Calf Woman, was born in the Okipa lodge at Like-a-Fishhook.25

The Red Feather Man’s Okipa—like all such ceremonies—began with a vision. In it, a holy man approached and revealed what was to come. Cedric saw an Okipa lodge with people lining up to go inside. “I saw men and women,” he recalls. “I saw Indians and non-Indians. I saw people from the five races of mankind—Red, Yellow, White, Black, and Brown.” What mattered, the holy man said, was not skin color but “the heart of the individual.” Those with “a good heart” would “enter the Okipa lodge. They must have the genuine love of mankind, and they must have humility. They must be genuine and sincere.”26

Thus it was that some sixty people of all hues gathered at On-a-Slant Village on June 11, 2011, to fulfill Cedric’s Okipa vision. The Black Mouth Soldier Society, the White Buffalo Cow Society, and the Goose Society were all present. So too was the Red Feather Man’s family: his uncle, Tony Mandan; his sister, Victoria Davis, and her husband, Dave; his nephews Daniel Davis and John Beaver; and his niece Janet Mandan, with her son Liam.

The Okipa suited the vision that inspired it. There was no piercing, no dragging of buffalo skulls. But Lone Man made his entry, and all the creatures came back. From morning to midnight, we danced and we danced, pausing to smoke, pray, tell stories, and ponder the Mandan way through the world.