PREFACE

The climate of North Dakota hardly ranks among North America’s most hospitable. Plains winters are long, windy, and bitterly cold. Rainfall is fickle, and summer temperatures fluctuate wildly. Yet for the Mandan people, this landscape is home. They have lived here, at the heart of the continent, for centuries, forging a compelling presence and an enduring lifeway in the face of serious obstacles. Many of their challenges have been military, diplomatic, or commercial in nature. But others, indeed the most daunting, have been ecological. Long before the arrival of Europeans and Africans from the so-called Old World, the Mandans and their forebears had learned to accommodate the vicissitudes of drought, climate change, and competition with others for coveted resources.

These challenges persist to the present day, but the arrival of strange peoples and species after 1492 added formidable new pressures to the mix. Among the foreign species, many of the most deadly were too small to be seen. These microscopic newcomers included the viruses that convey smallpox and measles, the bacterium that causes whooping cough, and possibly the bacterium that causes cholera. Other invisible pathogens, unidentified or unmentioned in the documentary record, may likewise have reached the Mandans in these years.

While the pathogens were invisible, their effects were not. People got sick, often with horrific symptoms, and died in large numbers. Indeed, the tragic effects of those pathogens can still be glimpsed near Bismarck and Mandan, North Dakota, where the outlines of ancient Mandan settlements mark the landscape even today. Some of these town sites—once vibrant social and commercial hubs—were abandoned after epidemics had struck. Some likewise reveal a sequence of defensive ditches that contracted as populations diminished.

The visible species that remade the Mandan world included powerful horses and scurrying Norway rats. European horses arrived first, spreading north from Spanish New Mexico and the southern plains and reaching the Mandans in the early to mid-1700s. But horses did not alter the basics of Mandan existence as they did for itinerant peoples like the Sioux, Crows, Arapahos, Blackfeet, and Assiniboines. By the second half of the eighteenth century, the Mandans had simply, and profitably, added horses to the marketable goods they bartered with others. Norway rats arrived later, aboard U.S. army keelboats in 1825. The animals feasted on the great stores of maize that Mandans kept in underground caches. Multiplying rapidly, they demolished the villagers’ prodigious corn supplies in a matter of years.

None of these diverse species arrived in isolation, and the consequences of Old World intrusions were mixed, numerous, and unpredictable. Horses, for example, invigorated travel across the continent’s interior grasslands and increased interactions among plains peoples. But this also meant they helped to spread infectious diseases, since their riders sometimes carried microbial infections. Meanwhile, rats depleted Mandan corn supplies at the very time when other pressures—related to diverse factors including horses and steamboats—reduced the number of bison that grazed near Mandan towns. The result was a nutritional scarcity that may have made the villagers more vulnerable when pathogens struck.

By 1838, the Mandan situation was dire: Their numbers had plummeted from twelve thousand or more to three hundred at most. That they survived is testimony to their resilience and flexibility on the one hand and their traditionalism on the other.

* * *

I am concerned in this book with encounters at “the heart of the world”—the Mandan name for their homeland—in modern North Dakota, where the Heart River joins the Missouri River. The encounters include my own. For me, the first came during research I did some years ago on the continent-wide smallpox epidemic of 1775–82, which afflicted the Mandans as it did so many others. Reports of smallpox in the upper-Missouri villages had intrigued me. How could it be, I wondered, that I knew almost nothing about this once-teeming hub of life on the plains? Why do the Mandans appear in the broad history of North America only when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent the winter with them in 1804–1805? The accounts I read confirmed my suspicion that significant holes persisted in our knowledge of early America. Places we knew remarkably little about had once cradled prosperous human settlements. The more I learned, the more I sensed that the Mandan story provided an alternative view of American life both before and after the arrival of Europeans.

It nevertheless took a trip to North Dakota to convince me. How could I write about a place I had not yet seen? Geography, landscape, and natural history have always appealed to me; they creep inexorably into my thinking and writing. So in August 2002 I went to North Dakota for the first time, just to see if it felt right.

In a grime-covered red Pontiac, I crisscrossed the western half of the state, where I was captivated by the rolling plains, the crumpled badlands, and the reassuring presence of the Missouri River, the geographic reference point to which I always returned. At Lake Sakakawea, formed by the completion of the Garrison Dam in 1953, I followed the Missouri’s shoreline southeast across the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. “Fort B,” as the locals call it, is the modern-day home of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples, officially designated the Three Affiliated Tribes. The center of tribal life is New Town, a sprawling community of wide streets, modest homes, and motley storefronts on the east shore of the lake. Here I filled my gas tank at the Cenex station and stocked up on groceries at the Super Valu market.

New Town was dusty and quiet on that first visit in 2002. Little did I know then that the community was about to face a twenty-first-century upheaval. Just a few years later, the steady rumble of tanker trucks along Main Street marked New Town’s transformation into an edgy boomtown, with resources strained to the limit. Fracking—the extraction of underground oil by hydraulic fracturing—had come to Fort Berthold. But in 2002, there were few visible signs of this impending turn of fortune.

From New Town, I drove two miles west on Highway 23, past Crow Flies High Butte and across the rickety Four Bears Bridge, soon to be replaced by a more accommodating span of the same name. Bridge and butte alike honor the memory of notable Indian leaders. On the far bank of the Missouri, really of Lake Sakakawea, I eyed the beige-and-brown tribal administration building from afar. Who was I to waltz in and announce I had come to write Mandan history? I wandered through the dim, boxy sprawl of the 4 Bears Casino, eerily animated by a cacophony of flashing lights and electronic sounds. I stayed longer at the nearby Three Affiliated Tribes Museum, where I studied an array of exhibits that as yet made only partial sense to me. I also met the museum’s director, Marilyn Hudson, a steadfast guardian of her people’s past and a font of living history.

My North Dakota travels took me off the reservation as well, to locations now designated state or national parks. Near the Montana–North Dakota border, I stopped at the Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center. Its view of the convergence of two great rivers prompted ruminations about the peoples who met at that site in times past: Assiniboines, Blackfeet, Crees, Crows, Lakotas, Hidatsas, Mandans, and an assortment of fur traders, not to mention the nomads who traversed the northern plains thousands of years before them. Small wonder that in 1828, just three miles away, the American Fur Company built Fort Union, a post that became a hub of commercial life as the fur trade rushed past the Mandans and toward the Rocky Mountains. Its reconstructed, whitewashed walls still beckon to travelers crossing the plains.

Back in the heart of Mandan country, below the Fort Berthold Reservation, I drove southeast through the little town of Hensler and nosed my rented car into Cross Ranch State Park. Here I hiked through wooded bottomlands, glimpsed flourishing native prairie, and spent a marvelous, breezy night camped beside the Missouri River. But not all of my explorations were so idyllic. I later pitched my tent at Bismarck’s General Sibley Park and passed a sweltering night listening to beer-infused merrymakers a few campsites away.

I also visited the great Mandan archaeological sites along the Missouri. I went to Huff Indian Village, where one can see the remains of a fifteenth-century settlement first occupied and fortified a few decades before Columbus sailed. I went to On-a-Slant Village, Chief Looking’s Village, and Double Ditch Village, three sites that date roughly to the years between 1500 and 1782, when the Mandans reached their apogee. For all their earlier trials and adaptations, it was here that they really saw their world transformed.

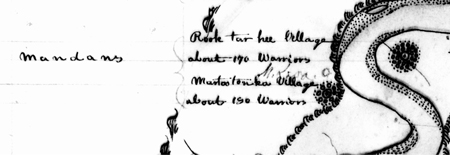

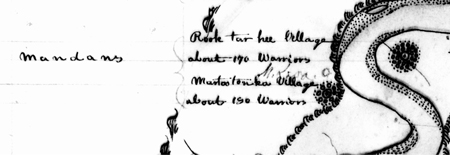

There were some important locations I could not visit. Among these were the sites of Ruptare* and Mitutanka, towns where Mandans were living when Lewis and Clark passed through. Ruptare now lies beneath the Missouri River’s shifting currents, which long ago carried its remains downstream. Mitutanka suffered an even more prosaic fate. Gravel-pit operators obliterated most remains of the town in the 1950s while selling off pulverized rock. Soon thereafter, the erection of an electrical power plant completed the destruction.1

Unlike the Mandan settlements of Mitutanka and Ruptare, the remains of several neighboring towns inhabited by Hidatsas still survive just a few miles to the north. At the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, visitors can wander over the grass-covered remnants of three great settlements marked by large circular depressions in the soil. These shallow basins—thirty, forty, even sixty feet in diameter—were once earth lodges, stout wood-and-turf homes built and maintained by Mandan and Hidatsa women. Today the town sites are silent. How different it must have been when thousands of Native Americans welcomed Lewis and Clark to their villages.

My 2002 trip to North Dakota clinched it: I wanted to write the Mandan story. Unfortunately, desire and execution do not always converge. My eye-opening journey to the heart of the world also included encounters with the very sparse documentary record pertaining to the Mandans before 1800. The dearth of material was daunting, but it led me to explore alternative approaches to research and narrative. I found myself learning and writing about archaeology, anthropology, geology, climatology, epidemiology, and nutritional science—any area of research that could give renewed substance to the Mandan past. The result is a mosaic I have pieced together out of stones from many quarries. Of course, such work of digging, weighing, and arranging is never complete; gaps remain for others to fill, using sharper eyes, fresh techniques, and different perspectives.

Given the obvious difficulties and limitations of the task I set myself, I decided from the start that it was far better to entertain possibilities than to ignore or dismiss them. Important pieces of the Mandan past continue to be elusive or downright inaccessible. But for me, the exploration of possibilities is an aspect of the historian’s task that kindles thoughtfulness, wonder, and apprehension alike. I hope this book, cobbled from such diverse materials, nonetheless has a feel of continuity and completeness, that there is a discernible design to the rocks and fragments I have assembled here. I realize, as I hope you will, that the writing of history is neither certain nor sanitary. It remains for scholars in the future to sort out what we misunderstand or cannot imagine today. I only hope that those scholars find the pursuit of Mandan history as affecting as I have. The creation of this book has influenced me every bit as much as I have influenced it.

Figure 0.1. Ruptare (“Rook tar hee”) and Mitutanka (“Muntootonka”) shown on a detail from William Clark’s route map of 1804 (Maximilian copy). Ruptare is the circular configuration on the east (right) side of the river, Mitutanka the similar configuration on the west (left) side.

Figure 0.2. The site of Mitutanka as it appeared in 2002, with the Basin Electric Power Cooperative’s Leland Olds Station. In 1822, the Mandans themselves moved Mitutanka downstream, where it became known as Mih-tutta-hang-kusch.