Conversation

Sometimes referred to as talking, chatting, visiting, jawing, small talk, or repartee, conversation involves the oral exchange of ideas, opinions, and sentiments. Loosely structured, it often flows along according to whims and inclinations with little purpose beyond visiting or “passing the time of day.” Allen Tate, in an essay titled “A Southern Mode of the Imagination,” argued that northern conversation was about ideas, whereas “the typical southern conversation is not going anywhere; it is not about anything. It is about the people who are talking.” An aspect of regional manners, Tate wrote, southern conversation is a way “to make everybody happy.” Ellen Glasgow in The Woman Within insisted that in the South “conversation, not literature, is the pursuit of all classes.” In the frontier South with dwellings miles apart and life lonely and often harsh, lengthy visits were common, and hospitality was extended even to strangers. Church meetings, court days, political rallies, funerals, and even hangings became occasions to socialize, to hear the news, and to discuss mutual concerns. At the country store loafers congregated, and in cold weather they clustered around the warm stove to play checkers or cards and swap yarns.

Southerners have long taken pride in being, and listening to, great talkers, making folk heroes of preachers, lawyers, politicians, and storytellers. Whether conversing in a lowly cabin, a white framed house, or a mansion, they reveled in loquaciousness. Young ladies mastered the art of “small talk”; matrons loved to gossip about household matters, child rearing, and sensational happenings. Thomas Nelson Page commends “the master of the plantation” as a “wonderful talker” who “discoursed of philosophy, politics, and religion.” When discussing hospitality Page reports, “The conversation was surprising: it was of crops, the roads, politics, mutual friends, including the entire field of neighborhood matters, related not as gossip, but as affairs of common interest which everyone knew or was expected and entitled to know.” In Charleston, New Orleans, Natchez, and other cities planters and professionals met in their social and literary clubs, welcomed distinguished guests, and engaged in enlightened repartee, sometimes over dinner or while sipping old wines.

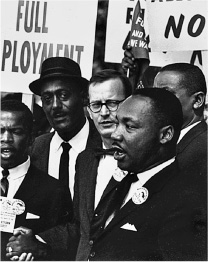

Swapping stories, Vicksburg, Miss. (William R. Ferris Collection, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Blacks, meanwhile, developed distinctive conversational skills. Zora Neale Hurston in Mules and Men (1935) recalled from her childhood in Eatonville, Fla., the men who gathered at the country store or on the front porch to exchange tales, and her works are filled with examples of black conversation, including the “lying” sessions when stories were swapped. Writers such as Ralph Ellison and Alice Walker structure their works around conversational lore.

In more recent times, for both blacks and whites, the front porch (the “gallerie” to Cajuns) attracted the family and their friends. Shaded perhaps by tall trees and equipped with rocking chairs and sometimes palm-leaf fans or ceiling fans, it was a place to relax, to watch passersby, and to welcome relatives, neighbors, the postman, a salesman, the minister—whoever happened to stop and “sit a spell.” In French Louisiana the visitor might be offered dark-roast coffee; in other areas, iced tea or lemonade. The mint julep sometimes encouraged joviality on plantation verandas. With the advent of radio, television, and air-conditioning, the front porches were enclosed or gave way to cooler interiors out of the heat and dust, and no longer were people as likely to pass the time with simple conversation.

WALDO W. BRADEN

Louisiana State University

Roger D. Abrahams, Southern Folklore Quarterly (vol. 33, 1968); Waldo W. Braden, The Oral Tradition in the South (1983); Merrill G. Christophersen, Southern Speech Journal (vol. 19, 1954); Everett Dick, The Dixie Frontier: A Comprehensive Picture of Southern Frontier Life before the Civil War (1948); Frank L. Owsley, Plain Folk of the Old South (1949); Allen Tate, Essays of Four Decades (1968).

Creolization

The earliest African slaves in the Lowcountry and on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia spoke various African languages that were often mutually unintelligible. The common language that they acquired was an English-based pidgin. An analogous situation occurred in southeastern Louisiana, where a French-based pidgin arose. Pidgin languages develop as a means by which speakers of diverse languages may communicate with one another. A pidgin has no native speakers: it is a second language by definition. But it became a native tongue when it was passed on to the American-born children of those enslaved Africans. Once a pidgin acquires native speakers, it is said to be a creole language. As a native tongue it must serve not merely the restricted functions of a pidgin but all the functions of a language. Gullah is a creole language developed by the descendants of enslaved Africans in South Carolina and Georgia. In Louisiana a French creole usually called Louisiana Creole developed.

The process of linguistic change in which two or more languages converge to form a new native tongue is called by students of linguistic change “creolization.” The creole language Gullah continued to evolve—both in inner form and extended use—in a situation of language contact. There was reciprocal influence of African and English features upon both the creole and the regional standard. The English contribution was principally lexical; the African contribution was principally grammatical.

The process of linguistic change provides a model for explaining other aspects of the transformation from African to African American culture. What might be called the “creolization of black culture” involves the unconscious “grammatical” principles of culture, the “deep structure” that generates specific cultural patterns. Such “grammatical” principles survived the Middle Passage and governed the selective adaptation of elements of both African and European culture. Herded together with others with whom they shared a common condition of servitude and some degree of cultural overlap, enslaved Africans were compelled to create a new language, a new religion, and indeed a new culture.

Not only was the structure of the new language a result of the creolization process, but the structure of language use was as well. The African preference for using indirect and highly ambiguous speech—for speaking in parables—was adapted by Americanborn slaves to a new natural, social, and linguistic environment. This aspect of the creolization process is strikingly evident in their proverbs. By employing the grammar of African proverb usage and the largely English vocabulary of the new creole language, African Americans were able to transform older African proverbs into metaphors of their collective experience in the New World. Some African proverbs were simply translated into the new vocabulary; others underwent minor changes. Still others retained the semantics of the African proverbs but completely transmuted the rhetoric into metaphors more meaningful to the new environment.

Naming patterns exemplify another way in which Gullah-speaking slaves preserved their African linguistic heritage while also combining aspects of it with English. The traditional African custom of “basket naming,” or bestowing of private names, continued into the 20th century. As late as the Civil War, all seven West African day names, as well as other African basket names, appeared on slave lists in the South Carolina Lowcountry. But African continuities were not manifested solely in the static retentions of easily recognized African names. On the contrary, behind many of the apparently English names of the slaves were African naming patterns. In many cases African meanings were retained with direct translation of names into English. Day names, in particular, were frequently translated into their English equivalents (e.g., Monday). But the creolization process, by which African means of using language were applied to a new tongue, produced such fresh seasonal basket names as Christmas. Similarly, black names revealed the adaptation to new places of the African pattern of naming after localities.

The creolization process was vividly exemplified in black storytelling. The folk narrative tradition of African Americans, like that of their African ancestors, was eclectic and creative. They took their sources where they found them, remembered what they found memorable, used what they found usable, and forgot the forgettable. Both inherited aesthetic grammars, and the realities of the new environment played mediating roles in that process. Animal trickster tales constituted the most numerous type of folk narrative among African Americans, as among Africans, but African Americans did not merely retain African trickster tales unchanged. On the contrary, the African narrative tradition was itself creative and innovative both in Africa and in America, where it encountered a strikingly different social and natural environment. The African American trickster tales indicate the black response to that new environment and efforts to manipulate it verbally and symbolically. In addition to animal trickster tales, the slaves narrated a cycle of human trickster tales in which the trickster role was not played by a surrogate slave—the rabbit—but by a real slave, John. Both animal and human trickster tales manifested continuities with African themes and with African traditions of indirect speech.

The study of linguistic creolization is a relatively recent phenomenon; the application of creolization theory to the study of African American culture represents a promising approach to understanding the transformation of diverse African cultures into African American culture.

CHARLES JOYNER

Coastal Carolina University

Melville J. Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (1941); Charles Joyner, Down by the Riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community (1984); Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (1978); Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (1982); Lorenzo Dow Turner, Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (1949, 2002); Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (1974).

Dictionary of American Regional English

The Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) seeks not to prescribe how Americans should speak or even to describe how people across the country do speak in formal or standard contexts. Instead, it documents the varieties of English that are not found throughout the country—those words, phrases, pronunciations, and grammatical features that vary from one region to another, that are learned at home rather than at school, or that are part of oral rather than written culture. The plan for the dictionary was devised by Frederic G. Cassidy and Audrey R. Duckert. It was carried out by Cassidy, Joan Houston Hall, and others. A unique feature of DARE is the use of maps in the text (with state sizes adjusted to reflect population density rather than geographic area) to show where particular words were collected during interviews with 2,000 people across the country. Whenever possible, editors assign regional labels that describe where the word or phrase is used. The DARE fieldwork, local newspapers, memoirs, and oral evidence provide good indications of both regional and social distributions.

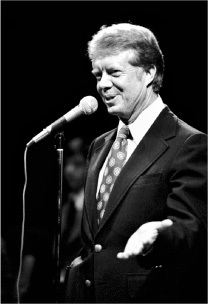

Frederic G. Cassidy, original editor and co-conceiver of the Dictionary of American Regional English (George E. Hall, photographer)

Analysis of the maps and of the regional labels used in DARE entries makes it clear that the South (by which DARE means southern and eastern Maryland, eastern Virginia, eastern and central North and South Carolina, southern and central Georgia, Florida, central and southern parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, as well as east Texas) still retains thousands of language features that reflect its distinctive cultural background and history. The region known as the South Midland, extending from the South as far west as Missouri, Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma, and northward into the southern parts of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, is the next most frequent regional label in DARE. And when labels referring to subregions such as the Southeast, South Atlantic, and Gulf states are also included, there is no question that the “South,” as defined in this Encyclopedia, is easily the most distinctive region of the country in its words, phrases, pronunciations, and grammatical constructions.

A very few examples are included here to illustrate some of the distinctively southern terms found in DARE: battercake, corn dodger, hopping John, hush puppy, and red-eye gravy for foods; cooter, hoppergrass, mosquito hawk, peckerwood, and piney-woods rooter for animals; cup towel, flying jenny, mourners’ bench, play-pretty, and rawhead and bloodybones for aspects of material culture; fixin’ to, for to, hisn/hern, might could, and y’all for grammatical and syntactic features; and co’cola, hep, janders, nekkid, and sallet for pronunciation variants. The index to the published volumes of DARE allows readers to go from the lists of entries labeled “South,” “South Midland,” and so forth directly to the dictionary’s entries.

Based on face-to-face interviews carried out in all 50 states between 1965 and 1970 and on an extensive collection of other materials (diaries, letters, novels, histories, biographies, newspapers, government documents, ephemeral notes, and in recent years, digital resources), DARE provides historical documentation for every headword and sense (there are approximately 50,000 senses in the first four volumes), and it dates every quotation used. Quotations from such prominent southern writers as William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, and Joel Chandler Harris, as well as from many lesser-known southerners, are used to provide illustrations of usage. This excerpt from Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust, for instance, is used at the entry for cup towel (a dish towel): “The sheriff stood over a sputtering skillet ... a battercake turner in one hand and a cuptowel in the other.”

Four volumes have been published to date: A–C (1985), D–H (1991), I–O (1996), and P–Sk (2002). The fifth volume of text (Sl–Z) is expected in 2009, to be followed by a volume of ancillary materials (including fieldwork data, contrastive maps, a cumulative index, and the bibliography) and an electronic edition.

JOAN HOUSTON HALL

University of Wisconsin

An Index by Region, Usage, and Etymology to the Dictionary of American Regional English, vols. 1 and 2 (1993) and 3 (1999); Frederic G. Cassidy and Joan Houston Hall, eds., Dictionary of American Regional English (1985– ); Joan Houston Hall, in Language in the USA: Themes for the Twenty-first Century (2004); Allan Metcalf, in Language Variety in the South Revisited, ed. Cynthia Bernstein, Thomas Nunnally, and Robin Sabino (1997).

Fixin’ to

Fixin’ to has developed in Southern American English as a phrase having numerous pronunciations, a complex origin, and a variety of meanings, the most familiar one indicating the immediate futurity of a proposed action. Thus, in I am fixin’ to go and She is fixin’ to fix supper the going and the fixing supper are soon to occur. In grammatical nomenclature fixin’ to is a phrasal auxiliary verb (it has also been called a “quasimodal,” “almost modal,” or “semiauxiliary” verb) that precedes and modifies a main verb. It has been well known in southern lore and everyday speech for almost two centuries, its first recorded usage being in 1829, in the Virginia Literary Museum (I’m fixing to go).

Fixin’ to has evolved new forms, functions, and meanings from existing words, following a universal tendency in languages. Its pronunciation often changes to fixin ta and may also be heard in the South as fikin ta, fisin ta, fikin na, or fix ta. During the Great Migrations of the early 20th century, fixin’ to moved out of the South with African American speakers who developed new forms and new pronunciations, such as fixin na, fin na, fit’n ta, fin ta, fit na, fi’in, and fin.

Fix maintains its original meaning, “to make firm, stable, or hold steady,” as well as meanings that later developed from this (“to fasten or attach,” then “to repair,” and then “to prepare”). Since preparing points toward a future occurrence, the meaning of futurity is applied to fix in the South. Sheisfixin’ to fix supper thus illustrates two distinct meanings: “She is getting ready to prepare supper.”

As a phrasal auxiliary fixin’ to precedes the main verb in a clause to influence the meaning of the time relationship. For instance, I’m fixin’ to leave (“I’m about to/getting ready to leave”) or I was fixin’ to leave when she arrived (“I was about to/getting ready to leave when she arrived”) signifies an imminent event intended to happen in the immediate future, indicating a psychological readiness as well as a physical one. I’m fixin’ to go home (“I’m going to go home”) gives a sense of future determination and immediate action, but when not intending immediate action, a speaker can use fixin’ to to convey a false promise or the subtle implication that an action is being (or has been) delayed. A speaker who says I was just fixin’ to do that may have been only procrastinating or perhaps did not intend to perform the action at all. Then the use of fixin’ to approaches irony.

Thus, fixin’ to may express futurity, immediacy, priority, definiteness, certainty, preparatory activity (psychological or physical), procrastination, or ironic contradiction. A speaker can manipulate these notions, and the interpretation of any given instance is determined by the context of the speaker and audience. Fixin’ to is therefore a highly complex form unique to the English language, one that cannot always be simply replaced by getting ready to, about to, or another phrase. Because of its great usefulness, southerners will probably resist any effort to replace it in their speech.

MARY ZEIGLER

Georgia State University

Frederic G. Cassidy, ed., Dictionary of American Regional English, vol. 2 (1991); Marvin K. L. Ching, American Speech (vol. 62, 1987); Mary B. Zeigler, Southern Journal of Linguistics (vol. 26, 2002).

Folk Speech

Folk speech has two distinct senses. The first refers to popular, vernacular, often local speech that differs from the standard, formal, textbook, and usually more widespread variety of a language. Although some writers have used the label to identify largely nonurban, uneducated speech, and some folklorists have incorporated this definition into their work, even the best-educated and highest-status speakers of a region may use this first sort of folk speech. It includes variation in pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary.

For pronunciation, linguistic geography profusely documents regional differences in individual words (e.g., greazy is more common in the South than greasy) as well as in general trends (e.g., the fact that southerners pronounce e before n or m like i, so that ten and hem are identical to tin and him). There are extensive differences in grammar, as in the past tense of verbs (Iseen him yesterday), and linguistic studies have also verified the popular perception that southerners’ vocabulary often differs from that of other Americans. The southerner’s use of y’all is perhaps the best example. Even the meanings of words shared with other regions are often distinct. A southerner who offers to carry you somewhere means to “give you a lift,” not hoist you up in his or her arms and transport you.

The American Dialect Society, which was founded in 1889, has been an institutional focus for the study of this first type of folk speech, and its publications American Speech (1925– ), Dialect Notes (1890–1939), and Publication of the American Dialect Society (1944– ) are among the most important. The study of folk speech in the South has often focused on the legacy of, or deviations from, British speech patterns in Appalachia or other rural areas. The nature of African American English, the influence of other languages, and the relationship between speech and social class have also been central concerns. Projects such as the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States and the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States show the broad distribution of speechways across the region. The specific vocabulary of the South is being richly documented in the Dictionary of American Regional English, and many items there qualify as folk speech in either the first or both of the senses here. Smoky Mountain vocabulary and grammar are thoroughly treated in the Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English.

The second type of folk speech is more in keeping with modern folklorists’ definition of folklore in general—that it has artistic expression. It is not highfalutin, in the most common sense of “artistic,” but it is something beyond the ordinary, something that calls attention to itself, making the listener think that the speaker is being playful or creative. While many examples of such speech may be innovative, it is still deeply rooted in the traditions of an area, and the South is perhaps the best-known and best-studied region for such folk expressions, proverbs, euphemisms, similes, metaphors, and the like. For example, raining like an old cow pissing on a flat rock in Arkansas gets much more immediate notice than It’s raining very hard. In short, the first is artistic expression, or folk speech of the second type.

Many expressions, proverbs, and the like are in fact folk speech in both senses of the term. They often differ from more widely distributed language (sense 1), but they also call attention to themselves through audacity, cleverness, subtlety, or other devices associated with folk linguistic artistry (sense 2). Speech that is based in and is uniquely valued by its own community is folk speech; however, that which is regional but is everyday talk is not, in the second sense of the term.

Thus, a southerner who says He’s so high he couldn’t hit the floor with his hat (that is, “drunk”) is using folk speech, but one who says I’m fixin’ to leave ‘getting ready’ or I might could go ‘might be able to’ is not, since the latter usages are ordinary in most southern speech communities. Nonsoutherners, however, who often take a romantic and/or prejudicial view of everything southern, tend to perceive any talk by the region’s natives as artistic folk speech. Many have similar attitudes toward African American English or some foreign-accented speech, varieties that outsiders view as performances rather than the ordinary usage of some speech communities. Such varieties are often the target of imitations, another indication that speakers who believe they use more mainstream varieties often assign folk value to the ordinary usage of others. In short, according to sense 2, well nigh anything a southerner says might be folk speech to a nonsoutherner.

Folk speech can be a word, a phrase, a style of speaking, or even less than a word. “Folk noises” have hardly been studied, though chants, calls, and imitations have figured in a few works, and the “rebel yell” is a famous folk cry. The elongated vowel in shiiiiit is clearly an extension of the so-called southern drawl into a specific word, one known and imitated even outside the South, particularly in situations in which the word expresses disbelief.

Also little studied, until recently, is folk speech having to do with stylistic tendencies. For example, the classical tradition in southern education left behind both place-names (Sparta, Athens) and personal names (Cato, Cicero). This, combined with a traditional knowledge of the Bible and a desire for “big words,” produced a genre known as “fancy talk” in African American speech and influenced southern pulpit styles in general, some examples of which combined learned words with rhythmic cadences and even rhyme:

!Never before had the universe received this annunciation, and never before had any man or woman received the salutation.

In the area of phrases and proverbial phrases, southern folk speech (and the study of it) shines. Vance Randolph, George P. Wilson, Archer Taylor, and Bartlett J. Whiting have compiled noteworthy collections, although not all of these deal only with southern speech. Among proverbial comparisons there is the pattern as X as a Y (or X-er than a Y and other obviously related forms), as in busy as a one-armed paperhanger, and so X that Y, asin so tight [that] he wouldn’t give a dime to see the Statue of Liberty piss across New York Bay. Most collections combine the grammatical forms cited above with the others—X enough to Y and too X to Y (both related to so X that Y), and to X like a Y (often interchangeable with some forms of as X as a Y). There are other minor comparative forms: look like a sheepkilling dog, run around like a chicken with it shead cut off, make more noise than 99 cows and a bobtailed bull.

Though comparisons dominate, a few other forms based on nouns (thestraw that broke the camel’s back), verbs (come a cropper), and prepositional phrases (in hot water) are included in most studies, along with other expressions not so easily classified grammatically. Some might be identified as threats (I’m going to jerk a knot in your tail); wisecracks and comebacks (Your feet don’t fit no limb, saidtoone who asks who?); exclamations and warnings (Katy bar the door!); insults (You don’t amount to a hill of beans); taunts (Redhead, cabbage-head, 10 cents a pound, directed to a red-haired person); boasts (Hooo-eee! I’m half horse and half alligator!); and miscellaneous sentential items (Hope in one hand and shit in the other and see which fills up first!). Such a classification is practical rather than theoretically exhaustive, and many of these items, although collected in southern venues, are surely more widespread.

Although the content of southern folk speech reveals a preoccupation with rural, traditional matters, newer items display changing attitudes and concerns. Growing evidence suggests that southerners more than any other Americans may assign particular importance to folk speech, in response perhaps to the negative image some outsiders have of southern speech in general. Nevertheless, southern folk speech is important to the region, usually has a distinct local flavor, and will likely be around as long as the culture exists.

DENNIS PRESTON

Michigan State University

Cynthia Bernstein, Thomas Nunnally, and Robin Sabino, eds., Language Variety in the South Revisited (1997); Frederic G. Cassidy et al., Dictionary of American Regional English (1985– ); James B. McMillan and Michael B. Montgomery, Annotated Bibliography of Southern American English (1989); Michael B. Montgomery and Guy Bailey, Language Variety in the South: Perspectives in Black and White (1986); Michael B. Montgomery and Joseph S. Hall, eds., Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English (2004); Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders, English in the Southern United States (2003); Vance Randolph and George P. Wilson, Down in the Holler: A Gallery of Ozark Folk Speech (1953).

Grammar, Changes in

The grammar of English in the American South has been evolving since the early 17th century, when the region began to be colonized by immigrants from southern and western England. Some grammatical features of Southern English can be traced to the language of these early settlers; others were introduced by English speakers arriving later from northern England, Scotland, and northern Ireland. Although American English in its early stages had the reputation of being relatively uniform (compared with British English), dialects began to emerge as settlement patterns developed; contact between European immigrants, African slaves, and Native Americans affected the language of different regions; and new grammatical features arose. In the South, distinctive variations became especially evident in such urban focal speech areas as Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans; in the mountains of the Appalachians and Ozarks; and in isolated coastal areas of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Chesapeake Islands of Virginia and Maryland, and Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia. All these regional varieties have continued to evolve, so that, contrary to popular belief, not even isolated coastal regions or the most remote mountain communities retain intact the English originally brought to them.

Southern English has also been subject to social forces, some of which have reinforced speech differences. Among the consequences of the slave trade and plantation culture were the emergence and the evolution of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as a means of maintaining black identity. The Civil War and Reconstruction reinforced distinct southern speech varieties. Other forces favored the sharing of linguistic features. Industrialization in the late 19th century led to urbanization and migration from the countryside. World War I and especially World War II brought many southerners out of comparative isolation. The advent of air-conditioning has more recently encouraged migration to the South. The civil rights movement led to greater integration and increased levels of education. As a result of these and other social forces, some stereotypically southern features are expanding, while others are declining or becoming associated with social or ethnic varieties.

Expanding Grammatical Features.

Some of the most salient grammatical features of Southern English remain strong and may even be spreading.

Second-person-plural pronouns. No feature is more closely identified with southern speech than you all (with the accent on the first syllable) and y’all to refer to more than one person, as in Are y’all coming over tonight? Some evidence suggests that y’all is being used increasingly by young southerners and by people of all ages in other parts of the United States. At the same time, you guys, once restricted to the North, is gaining favor among some southerners as an informal form of addressing multiple listeners. You’uns, a form having the same meaning and once common in Appalachian parts of the South, is disappearing rapidly.

Double (or multiple) modal verbs. English generally does not permit two modal auxiliary verbs (may, might, can, could, shall, should, will, would) to occur together, but southerners frequently combine them, as in I might could do it, to express a degree of tentativeness, indirectness, or politeness. Double modals are holding strong in the South and sometimes show up outside the region as well, especially among African Americans, whose linguistic roots are in the region.

Fixin’ to. The expression fixin’ to means something like about to or preparing to, asin I was just fixin’ to leave. Its use is widespread among all regional and social groups in the South, and it is often acquired by nonsoutherners who move to the region.

Declining and Restricted Features.

Some features that are evident in records from earlier centuries have become less common or are now associated with certain ethnic or social varieties in the southern United States.

Invariant be. In Southern English the uninflected form be (occasionally bes) may be used as a main verb or an auxiliary, where general usage requires am, are, is, was, or were. It was common in colonial America, but in modern Southern English its use has declined among whites. In AAVE, where it signifies habitual action, it may be used with singular or plural subjects, especially in the construction be plus a verb plus -ing, asin They [or he] be working in Texas. Along similar lines, omitting the main verb be, asin You ugly, is declining in usage among whites in the South, though use of the feature is still evident in AAVE.

Third-person zero suffix. English generally requires an -s ending for verbs in the present tense when they have a third-person singular subject. In Southern English, the suffix may be omitted, somewhat more often if the subject is a pronoun, as in She stay in Texas. Evidence of this feature has been found in written records from 16th-century England and the 19th-century American South. It is now more common in AAVE than in general southern speech.

Zero plural. The English plural is generally formed by adding an -s to nouns. When certain nouns are preceded by a number, Southern English allows the -s to be deleted, as in I walked six mile to school every day. The Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States (LAGS) showed that in the 1970s this feature was more than four times more likely to be used by the oldest speakers than by the youngest speakers in its survey, suggesting that it is disappearing.

Zero possessive. English generally uses -’s on nouns to signal possession. Southern English occasionally omits the -s suffix, as in The man hat is on the floor. Today this is commonly associated with AAVE.

Third-person-plural -s and plural was. General English has no ending for verbs in the present tense when the subject is you or a plural noun or pronoun. Southern English sometimes adds an -s to the verb if the subject is a noun, as in My brothers works at night (but not They works at night). The feature was present in the English of Ulster Scots settlers. In addition, past-tense were may be replaced by was, asin We was all at home. Research shows these usages are declining today and are associated with working-class speech.

Liketa or liked to. Southern English uses liketa preceding a past participle verb to mean nearly, asin I liketa died. Associated now with rural working-class speech, liketa has been declining among younger generations.

A-prefixing. The structure a- plus a verb plus -ing, asin He come a-runnin’, was once common in both British and American dialects, but it is declining in general southern speech. LAGS found the feature to be associated with older, less-educated speakers. It may still be heard in the Appalachian region and in other relatively isolated communities, such as the islands of the Outer Banks in North Carolina.

Irregular relative pronouns. Whereas English generally requires a relative pronoun in such expressions as thepeople who/that live in the South, Southern English may omit the who or that. In addition, what is occasionally used as a relative, as in the people what live in the South. These features are now declining.

Nonstandard preterits and past participles. Many varieties of English have nonstandard irregular verb forms, as in I seen him do it, or I’ve knowed them for years. Verb forms were in flux in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, and some British relic forms, such as clum ‘climbed,’ holp ‘helped,’ knowed ‘knew/known,’ and riz ‘rose/risen,’ may be heard in the South, though their use is declining. LAGS reveals that younger people and those of higher socioeconomic status are less likely to use such past-tense and past-participle forms as come ‘came,’ growed ‘grew/grown,’ eat ‘ate/eaten,’ drownded ‘drowned,’ or run ‘ran.’Incontrast, dove ‘dive,’ is used more often by younger, better-educated speakers, even though it was once considered a nonstandard form.

Perfective done. In Southern English done sometimes replaces have as an auxiliary verb, as in I done forgot what he wanted. Documented in early 19th-century usage, this feature is declining. Like nonstandard preterits, it characterizes the speech of older, working-class southerners.

Other Grammatical Features of Southern English.

Some grammatical features are limited to regions within the South; Appalachian English, for example, has possessive forms ending in -n at the end of a phrase, as in Is this yourn? Some are limited to AAVE; for example, remote-time been (stressed) connotes distant past, as in She been write the letter (i.e., a long time ago). Some, such as ain’t, double negatives (It ain’t gonna do no good), or them in place of those (How do you like them apples?), are common not only in the South but in other regions as well. In spite of the varieties of ways in which southern grammar is changing, there is no evidence that it is disappearing as a distinguishing attribute of southern speech.

CYNTHIA BERNSTEIN

University of Memphis

E. Bagby Atwood, A Survey of Verb Forms in the Eastern United States (1953); Cynthia Bernstein, in English in the Southern United States, ed. Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders (2003); Patricia Cukor-Avila, in English in the Southern United States (2003), ed. Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders; Crawford Feagin, Variation and Change in Alabama English: A Sociolinguistic Study of the White Community (1979); Michael Montgomery, in From the Gulf States and Beyond: The Legacy of Lee Pederson and LAGS, ed. Michael B. Montgomery and Thomas E. Nunnally (1998); Lee Pederson et al., eds., The Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, 7 vols. (1986–92); Edgar W. Schneider, in English in the Southern United States, ed. Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders (2003); Jan Tillery, in Language Variety in the South: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Michael Picone and Catherine Evans Davies (forthcoming); Jan Tillery and Guy Bailey, in English in the Southern United States, ed. Stephen J. Nagle and Sara L. Sanders (2003).

Illiteracy

Inability to read and write in any language has been the conventional definition of illiteracy and the basis of most illiteracy statistics. The concept of “functional” illiteracy was advanced during World War II as a result of the U.S. Army experience with soldiers who “could not understand written instructions about basic military tasks.” The South has exceeded the rest of the nation in illiteracy, whether defined in functional terms or as the inability to read and write in any language. Information from the U.S. census of 1870 illustrated the South’s heritage of illiteracy. No area of the region had less than 12 percent illiteracy. The cotton-culture regions, particularly the river valley and delta areas and the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, were 40 percent or more illiterate. The South was agricultural, and agriculture then depended not on science but on traditional practice—learning by doing rather than by reading. The 1870 census found 4.53 million persons 10 years of age and older unable to read in the nation; 73.7 percent of them resided in the South. Four-fifths of blacks were illiterate at that time.

The agricultural economy rested upon a sparsely distributed population, the use of child labor that discouraged school attendance, and a prejudiced and often fatalistic people who lacked the means for upward mobility in the expanding industrial system of the nation. The church was more important as a social institution than the school; word of mouth, song, and story were prominent means of cultural transmission. Under these conditions illiteracy served to conserve tradition and retard cultural change, whereas a more general literacy would have accelerated adaptation and change. Said a Jasper County, Miss., man, “My grandfather—he raised me—figured going to school wouldn’t help me pick cotton any better.”

When the education of a generation of children is neglected, the deficiency persists throughout a lifetime. Teaching adults to read has not been as effective in eliminating illiteracy as have mortality and out-migration from the South. The neglect of a generation of schoolchildren during the Civil War (those 5 to 14 years of age in 1860) resulted in higher illiteracy rates for the native white population in 1900 (who then were 45 to 54 years of age) than for either the preceding or succeeding generation.

A decline in illiteracy has occurred in the South and the nation. As educational benefits were extended to blacks through both public and private schools (including schools sponsored by religious groups, such as the Congregational Church, and by private foundations, such as the Rosenwald Fund), illiteracy rates dropped.

The change in illiteracy in Georgia from 1960 to 1970 illustrates the source of gains and losses of illiterates in a state. The number of Georgia illiterates in 1960 was reduced by 45 percent by 1970. Some 22,530 were estimated to have died during the decade, and 23,840 were lost through out-migration. The Adult Basic Education Program of the state taught 14,380 to read during the period. However, 6,290 new illiterates, aged 14 to 24 years in 1970, entered the category. This new group testifies to the failure of the family and the school to inculcate literacy skills. The National Center for Education Statistics in 1992 showed that the South still scored lower than any other region on literacy measures.

The 2000 census showed that 9 of the 11 states with less than 78 percent high school graduates are in the South. In 1980 the South had approximately 398,000 illiterates, according to estimates based on the 1980 census and the November 1979 Current Population Survey. The distribution by color was white, 44.9 percent; black, 51.4 percent; other nonwhite, 3.7 percent. By age, illiterates were distributed as follows: 14–24 years, 9.2 percent; 25–44 years, 17.0 percent; 45–64 years, 32.2 percent; and 65 years and older, 41.6 percent. These are individuals unable to read and write, according to census definitions; functional illiterates are more numerous.

In general, illiterates have lower learning capacity, are more likely to be welfare recipients, and have higher rejection rates for military service. If female, they have higher fertility rates, and instances of infant mortality among illiterates are always higher. There is more illiteracy in rural than in urban areas.

ABBOTT L. FERRISS

Emory University

Sterling G. Brinkley, Journal of Experimental Education (September 1957); John K.

Folger and Charles B. Nam, Education of the American Population (1967); Eli Ginzberg and Douglas W. Bray, The Un-educated (1953); Historical Statistics of the United States to 1970 (1975); Carman St. John Hunter with David Harman, Adult Illiteracy in the United States: A Report to the Ford Foundation (1979); U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports; Sanford Winston, Illiteracy in the United States (1930).

Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States

Directed by Lee Pederson of Emory University, the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States (LAGS) is a constituent of the American Linguistic Atlas or Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada project. It reports the results of an extensive survey of regional and social dialects of English in eight southern states: Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas (as far west as the Balcones Escarpment). It is the most comprehensive source of information available on the English of the South. Fieldwork for LAGS was begun in 1968, and the last of seven interpretive volumes that describe the research and summarize its results was published in 1992. The LAGS basic materials provide primary texts (in the form of responses to questionnaire items) for the study of English in the region and a description of the sociohistorical and sociolinguistic contexts necessary for their interpretation. The LAGS interpretive volumes inventory dominant and recessive patterns of linguistic usage in the Gulf states, identify and characterize the primary regional and social varieties of the region, and identify areas of linguistic complexity that require further study. More generally, LAGS provides a historical baseline for Southern English against which future linguistic developments can be measured and from which earlier varieties can be reconstructed. That baseline encompasses roughly the period between 1880 and 1940, the decades during which most LAGS informants were born (note, however, that the oldest informant was born in 1870 and the youngest in 1965). Both the design and the implementation of LAGS reflect its historical focus.

Tape-recorded interviews (or field records) with 1,121 informants in 699 localities in 451 counties comprise the basic data for LAGS. The informants include 594 men and 527 women, and 239 are African American (blacks were interviewed in all areas where they exceeded 20 percent of the population in 1930, before the effects of the Great Migration were fully realized). Both the average age (62.24) of informants and the overrepresentation of the less-educated (38.62 percent have an eighth-grade education or less) reflect the historical orientation of LAGS.

A series of analogs reduces the 5,300 hours of tape-recorded speech in the LAGS field records to graphic formats at various levels of abstraction. The protocols are the primary and most concrete analog of the field records. Containing phonetic transcriptions both of target items that were elicited by an 800-item questionnaire and of other useful phonological, grammatical, and lexical data that occurred during interviews, the protocols serve as comprehensive guides to the field records; their 121,000 pages of phonetic transcriptions are a major source of evidence on Southern English as well. Each protocol is conveniently summarized in an idiolect synopsis, a one-page abstract of its phonological, lexical, and grammatical substance, and the entire contents of all of the protocols are captured in the concordance, an alphabetical listing in normal orthography of every phonetically transcribed item and its place of occurrence in the LAGS protocols. University Microfilms published the protocols and idiolect synopses, along with the LAGS questionnaire and guide to phonetics and protocol composition, as LAGS: The Basic Materials on microfiche and microfilm in 1981; The Concordance of Basic Materials followed in 1986.

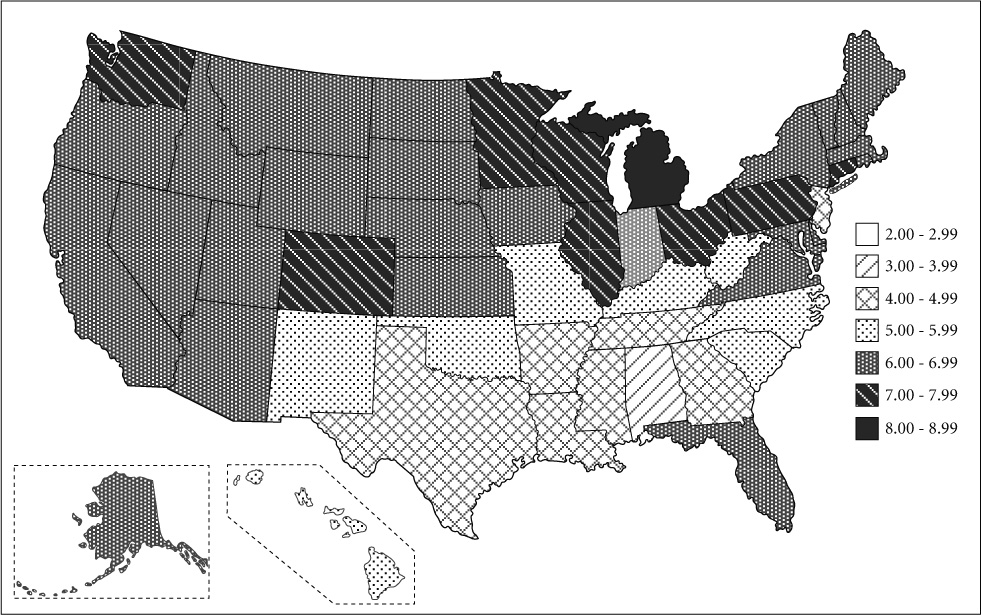

These microform texts serve as the input to still another analog, a set of computer files that rewrite LAGS data in ASCII format. When the computer files are combined with a series of mapping programs (both available from the Linguistic Atlas Project at the University of Georgia), they allow users to create their own maps and provide a kind of automatic linguistic atlas in electronic form. These files also form the basis of the seven interpretive volumes published by the University of Georgia Press. Those volumes include a handbook, which summarizes the LAGS methodology, informants, and communities; a general index, which summarizes the contents of the concordance; and a technical index, which summarizes the contents of the computer files. The other four volumes, the Regional Matrix and the Regional Pattern (vols. 4 and 5) and the Social Matrix and the Social Pattern (vols. 6 and 7) summarize many of the substantive results of LAGS and provide a useful overview of regional and social variation in the English of the Gulf states. The LAGS interpretive volumes (4–7) include information both on the distribution of individual linguistic features and on those combinations of features that produce regional patterns. Map 3, for instance, shows the regional distribution of chigger and red bug, two synonyms for a tiny bug in the grass that burrows into the skin and causes itching. Map 5 shows how LAGS uses the distribution of chigger in combination with three other features (red worm [a worm for fishing], an intrusive uh between the b and r in umbrella, and a strong r pronunciation in March) to help identify and delimit a Highlands pattern in the English of the Gulf states, a pattern that is also characterized by the use of such terms as French harp ‘harmonica,’ tow sack ‘burlap bag,’ barn lot ‘barnyard,’ and green beans (as opposed to snap beans). Using quantitative distributions of similar combinations of lexical, phonological, and grammatical features, LAGS identifies 20 subregional patterns that comprise two basic regional configurations, Interior and Coastal. The Eastern Highlands serves as a focal area (i.e., core or cultural hearth) for the former, and the Central Gulf Coast/Lower Delta serves as the focal area for the latter.

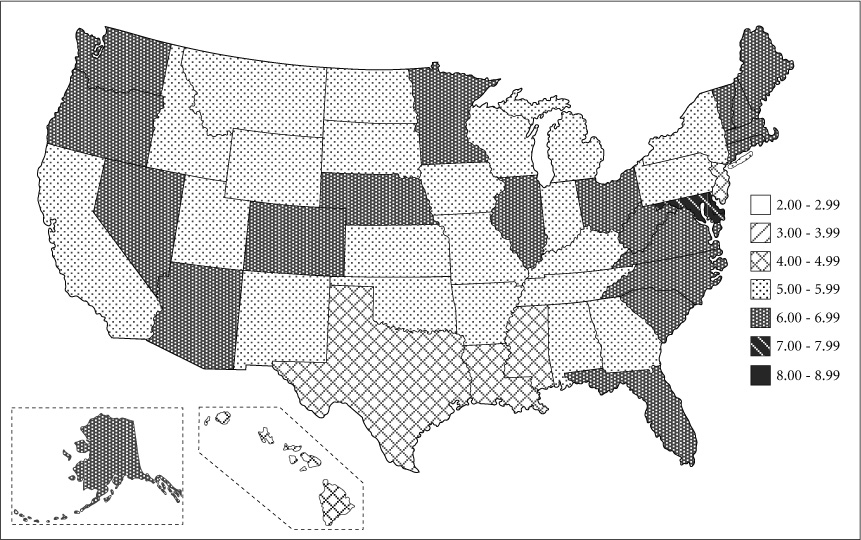

LAGS also identifies 20 types of social markers in the English of the Gulf states; these often interact with regional patterns in complex ways. The social markers reflect categories of race (black and white), sex, age, and education either in isolation or in combination. For example, LAGS identifies 31 features as characteristic of African American speech, with about half of these further subcategorized by age and education; 35 features are identified as primarily white. The occurrence of monophthongal or flat /ai/ in right (pronounced something like raht), a white social marker, illustrates the complex relationship between social markers and regional patterns. While the vast majority of the LAGS informants who have this feature are white (91.66 percent), as Map 6 shows, flat /ai/ also has a complex regional distribution, occurring primarily in the Eastern Highlands and the Ozarks; in the Piney Woods of south Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana; and in Texas. This kind of interaction between social markers and regional patterns gives southern speech much of its richness and complexity. Among the many virtues of LAGS is its capacity for capturing those interactions. LAGS thus maps and provides the raw material for researchers to chart the almost infinite detail of Southern English, and its data on the social patterning deepens our understanding of language change and variation in the region’s speech.

GUY H. BAILEY

University of Missouri–Kansas City

Guy Bailey and Jan Tillery, American Speech (vol. 74, 1999); Michael Montgomery, American Speech (vol. 68, 1993); Lee Pederson, in American Dialect Research, ed. Dennis Preston (1993); Lee Pederson et al., eds., Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, 7 vols. (1986–92).

Map 5. Highlands Pattern 4 (Source: Lee Pederson, Susan McDaniel, and Carol Adams, Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, vol. 5, Regional Pattern [1991], p. 73; cartography by Borden D. Dent)

Map 6. Map 50 (Source: Lee Pederson, Susan McDaniel, Guy Bailey, and Marvin Bassett, eds., Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, vol. 7, Social Pattern [1992], p. 151; cartography by Borden D. Dent)

Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States

The Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (LAMSAS) is the largest segment of the American Linguistic Atlas or Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada project, which was designed to survey the regional and social differences in spoken American English. LAMSAS covers the region from New York state south to Georgia and northeastern Florida, and from the eastern coastline as far west as the borders of Ohio and Kentucky. Along with Hans Kurath’s Linguistic Atlas of New England (conducted in the early 1930s and published 1939–43), LAMSAS treats the primary settlement areas of the earliest states of the United States. LAMSAS consists of interviews, the transcriptions from which are in fine phonetic notation, with 1,162 selected, native informants from 483 communities (usually counties) within the region. Interviews often required six to eight hours to complete; they were conducted with a questionnaire of 104 pages, averaging seven items per page, designed to reveal regional and social differences in everyday vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. Field-workers often avoided asking questions directly, in favor of more conversational interviews rich in local lore. In the days when the primitive machines that were available could record only short segments, phonetically trained field-workers wrote down in fine phonetic notation words and phrases that matched the intentions of the questionnaires. Initial fieldwork was conducted by Guy Lowman, aveteran of the New England survey, beginning in 1933. After Lowman’s death in a car crash in 1941, Raven McDavid largely completed the remaining interviews in upstate New York, Georgia, and South Carolina by 1949.

The speakers selected for LAMSAS and other atlas interviews were longtime residents of their communities, generally of middle age through the oldest living generation. They came from three different social strata: folk speakers (with little education or social involvement), common speakers (with a high school education and more social activity), and in about one-fifth of the communities, cultivated speakers (with a college education or its equivalent in experience and with wide exposure to high culture). Forty-one African American speakers were interviewed in the South Atlantic area, which represented forward thinking at the time, though not yet equal representation in numbers. LAMSAS thus records the English spoken along the Atlantic Coast in the second quarter of the 20th century among people of different social positions and degrees of education. It provides a benchmark for varying forms of the English language for a particular region at a particular time, with special reference to the development of the language in the late 1800s, when most of the interviewees were born and grew up. The significance of LAMSAS is thus principally historical. Along with the New England atlas, LAMSAS is also the key to making the best use of all the other regional atlas projects, which document the English spoken in secondary and tertiary American settlement areas (such as the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States). The Handbook of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States describes the methods, speakers, and communities of the project. LAMSAS, therefore, occupies a place beside other major projects in the history of the English language, and its survey data provided the basis for the first truly detailed delineation of southern speech. Unlike the Dictionary of American Regional English, a complementary project that seeks to record all identifiable “dialect” forms, LAMSAS seeks to define the typical, everyday language of Americans as that speech differed among the speakers of its region.

Even before LAMSAS interviews were complete, Hans Kurath published his Word Geography of the Eastern United States (1949) on the basis of New England and existing LAMSAS data (for the South, this included Virginia, West Virginia, and North Carolina). This volume described the basic pattern of American English dialects in three largely east-to-west bands, Northern, Midland, and Southern, which largely correlated with 18th-century settlement patterns. These dialect regions were confirmed in Kurath and McDavid’s Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States (also based on atlas data). Southern dialects were further subdivided into Upland Southern (also known as South Midland or Upper Southern) and Coastal Southern (also known as Plantation Southern or Lower Southern). Coastal/Plantation Southern was found across the survey area in places where the land could support plantation agriculture, while Upland Southern/South Midland speech was found in areas that generally could not, whether because the land was mountainous or too poor in quality to support large-scale agriculture. Raven McDavid wrote numerous articles using LAMSAS evidence, for example, showing the complex interrelations between the pronunciation of /r/ and South Carolina society and defending the speech of African Americans against popular stereotypes while demonstrating its status as a dialect of American English.

LAMSAS data is now becoming available online, along with information and data from other surveys of the American Linguistic Atlas Project, at <http://www.lap.uga.edu>. Speakers’ responses, in standard spelling (for some items also in Atlas phonetic transcriptions), are recorded in separate data tables for each question. Each response is accompanied by coding to identify the speaker, comments by speakers and field-workers, and information when necessary on the special status of a response (i.e., if it was suggested, heard, collected from an auxiliary informant, or otherwise doubtful or noteworthy). It is possible to browse the responses given for different questions, to search for words and phrases across all of the questions so far entered into the database, and to make maps online of where LAMSAS speakers said particular words and phrases. The size and detail of the LAMSAS digital database has enabled new kinds of linguistic analyses, for example, complex statistical processing and implementation of geographical information systems. Both the paper records and digital presence of LAMSAS and the American Linguistic Atlas Project are maintained at the University of Georgia, under the direction of William A. Kretzschmar Jr.

WILLIAM A. KRETZSCHMAR JR.

University of Georgia

William A. Kretzschmar Jr., American Speech (vol. 78, 2003); William A. Kretzschmar Jr., ed., Dialects in Culture: Essays in General Dialectology by Raven I. McDavid Jr. (1979); William A. Kretzschmar Jr. and Edgar W. Schneider, Introduction to Quantitative Analysis of Linguistic Survey Data: An Atlas by the Numbers (1996); William A. Kretzschmar Jr., Virginia McDavid, Theodore Lerud, and Ellen Johnson, eds., Handbook of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (1993); Hans Kurath, A Word Geography of the Eastern United States (1949); Hans Kurath and Raven I. McDavid Jr., The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States (1961).

Linguists and Linguistics

The formal study of language in the South has flourished for three-quarters of a century, led by linguists, academic institutions, projects, and conferences that have documented, analyzed, and mapped the region’s languages. In 1989 a book-length bibliography listed nearly 4,000 published books, articles, reviews, and notes on the history, vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, place-names, personal names, and other aspects of the region’s English; the number of items approaches 5,000 today. This literature reveals the English of the American South to have a multiplicity of varieties unmatched by any other region of the country, a far cry from outside perceptions and portrayals of Southern English as uniform.

Shortly after fieldwork for the Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada commenced in 1928, the project began work in the South Atlantic states of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina interviewing mainly older, less-educated, and less-traveled speakers in an effort to document thousands of individual usages and to employ these both to map regional variations and to outline dialect areas, especially as these reflected settlement history. Fieldwork for the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States lasted from 1933 to 1974, under the direction of Hans Kurath, first of Brown University and then the University of Michigan, and later of Raven I. McDavid Jr. of the University of Chicago. The Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, directed by Lee Pederson of Emory University from 1968 to 1992, encompassed eight states from Florida and Georgia to Texas and completed atlas work in the southern states.

Among the more eminent scholars of language of an earlier generation working at southern institutions and making major contributions to scholarship on the region’s language have been James B. McMillan (University of Alabama), Norman Eliason (University of North Carolina), Claude Merton Wise (Louisiana State University), Lee Pederson (Emory University), Archibald Hill (University of Texas), and Juanita Williamson (LeMoyne-Owen College). The most prolific and influential linguist to write on the region’s English was the South Carolinian Raven I. McDavid Jr. of the University of Chicago. A number of the contributors to this volume are linguists well known for their more recent research into southern language(s). Until very recently nearly all academics studying the South’s English have been natives, but this is increasingly less so today. Indeed one of the earliest to document local variations in African American speech (in the 1830s) was the German Francis Lieber, professor of political economy at South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) and founding editor of the Encyclopedia Americana. While these and other academics have made major scholarly contributions, it is noteworthy that the region’s language has always fascinated a wide spectrum of lay-people, who have engaged for decades in collecting, debating, exploring, and speculating about the meanings and origins of words and other usages, both in print and elsewhere.

The earliest universities to offer doctoral-level study in the field were the University of North Carolina and the University of Alabama, both of which established departments of linguistics in the 1940s. They were followed by the University of Texas, Georgetown University, the University of Florida, the University of South Carolina, the University of Georgia, and Louisiana State University. These and other institutions provide advanced training in the complete range of linguistic specialties, theoretical and applied.

A major advance in the region was the creation in 1969 of the Southeastern Conference on Linguistics (SECOL), whose object is the scholarly study of language in all its aspects. SECOL, which for many years held semiannual meetings (now annual), is currently headquartered at Auburn University and publishes a scholarly journal, Southern Journal of Linguistics, through the University of Mississippi. The Linguistic Association of the Southwest, whose territory overlaps with that of SECOL, was founded in 1972 and publishes Southwest Journal of Linguistics. Three major conferences in the Language Variety in the South series have gathered a wide array of scholars to present current research at the University of South Carolina (1981), Auburn University (1993), and the University of Alabama (2004).

MICHAEL MONTGOMERY

University of South Carolina

William A. Kretzschmar Jr. et al., Handbook of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (1993); James B. McMillan and Michael B. Montgomery, Annotated Bibliography of Southern American English (1989); Michael B. Montgomery and Guy Bailey, eds., Language Variety in the South: Perspectives in Black and White (1986); Lee Pederson et al., Handbook of the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States (1986).

Literary Dialect

Serving as comic device, signifier of social status or regional background, and component of literary realism, the tradition of representing dialectal speech in American literature came into its own in the second quarter of the 19th century. Early works drew on several regionally associated varieties of American English but are most strongly and most often connected to depictions of southern speech, black and white. These representations, beginning with the American humor tradition, often functioned as comic tropes or as attempts at realistic speech. Some of them, however, reinforced social distance between the dialect speakers and the presumed standard-speaking author and audience, as a way of poking fun at or condescending to less-educated, lower-class, rural speakers, particularly African Americans and southerners of all races.

The decline of the southern frontier, already taking place a generation before the Civil War, and the resulting nostalgia for disappearing ways of life led to the “old southwestern” humor tradition, with Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri comprising the “southwest” or southern frontier. With this came the first major wave of American dialect writing. Augustus Baldwin Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes (1835) was among the first and most influential of this genre. The frontier settings and themes of its sketches were supported by the speech of uneducated frontier characters, with characterizations and descriptions that were well received by audiences and critics. One Longstreet character, Billy Curlew, exemplifies the colorful speech used in these frontier characterizations: “Well dang my buttons, if you an’t the very boy my daddy used to tell me about,” exclaims Billy upon meeting the narrator of “The Shooting Match.” Other writers soon contributed to the genre, including George Washington Harris of Tennessee, William Tappan Thompson of Georgia, Charles F. M. Nolan of Arkansas, William Gilmore Simms of South Carolina, Henry Clay Lewis and Thomas Bangs Thorpe of Louisiana, and Hardin E. Taliaferro and Johnson Jones Hooper of North Carolina, all best known for works that appeared in the 1840s or 1850s. They represented southern frontier characters speaking a nonstandard dialect, which emphasized these characters’ lack of sophistication, social status, and education. For example, Thompson’s Major Jones character, who appears in many sketches, often finds himself in urban settings where the country-bred Jones stands out in part because of his speech. In one sketch, he visits the “opery,” but he “couldn’t hardly make out hed nor tail to it, though [he] listened at ’em with all [his] ears, eyes, mouth, and nose.” Jones concludes that “a body what never seed a opery before would swar they was evry one either drunk or crazy as loons, if they was to see ’em in one of ther grand lung-tearin, ear-bustin blowouts.” The lack of sophistication was further highlighted by the contrast between the dialectal speech of the characters and the standard speech of the narrator. This popular convention of the prewar humor genre highlighted the social distance between the authors, who were generally educated, upper-class members of their communities—Longstreet was a superior court judge, for example, while Thorpe was a newspaper editor and politician—and the “folk” characters who peopled the stories. That distance was echoed within the audience of the literature, who, unlike many featured characters, had access to literacy and reading materials.

After the Civil War, southern speech continued to be well represented in American dialect writing. “Local color” writers focused on the idiosyncrasies, including speech, of particular regions and their inhabitants, contributing to the development of dialect writing as well as to the rise of realism in American fiction, in part through local color writers’ attempts to reproduce realistic scenes and speech. The popularity of writers such as George Washington Cable and Kate Chopin of Louisiana, Mary Murfree of Tennessee, Martha Strudwick Young of Alabama, Ruth McEnery Stuart of Arkansas, and Joel Chandler Harris of Georgia (whose Uncle Remus stories were known worldwide) resulted in the increasing use of dialect as a mimetic device (a literary device used to imitate reality). For example, Cable’s characters speak a variety of English steeped in Louisiana French Creole, as exemplified in the speech of the title character of his 1883 novella Madame Delphine, who asks a friend to care for her daughter should any harm befall Madame Delphine: “I wand you teg kyah my lill’ girl.”

Toward the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th, the American realistic short story and novel evolved, as did the use of literary dialect, with characters and situations that lent themselves to portrayals of realistic speech. Writers associated with the local color movement and the rise of realism, including Cable, Chopin, Charles W. Chesnutt of North Carolina, and Mark Twain, whose native Missouri was part of the “old Southwest,” led the late-century use of dialect to enhance realism in fiction, perhaps best exemplified by Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). In the 20th century the work of Jesse Stuart of Kentucky, Lexie Dean Robertson of Texas, and William Faulkner and Eudora Welty (both of Mississippi), among many others, featured realism in southern literary dialect.

Realism was not the only goal of literary dialect in late 19th- and early 20th-century fiction. Some authors used dialect to mark characters as nonstandard or inferior in relation to narrator, author, or audience. One device, “eye dialect,” involved the use of alternative spellings that look different on the page but do not represent alternative pronunciations (for example, wuz for was or whut for what), which sometimes contributed to negative characterizations. While some writers have used eye dialect in ways that do not necessarily stigmatize the speaker, the device can also function simply to mark a speaker as “other,” particularly as a less-educated or socially or racially inferior person, without providing any real information about that person’s dialectal pronunciations.

Both black and white authors have frequently represented the speech of southern blacks. The portrayal by whites sometimes had less to do with realism in characterization than with the reaction of white writers and audiences to changes in the social order during and after Reconstruction. This is seen especially in works of the plantation tradition, an offshoot of the local color movement. In this tradition, which capitalized on white nostalgia for an idealized version of the antebellum South, white authors such as Thomas Nelson Page of Virginia and Thomas Dixon of North Carolina used black dialect primarily to differentiate African Americans from whites in the service of glorifying slavery and rationalizing continuing racial inequality. The “frame narration” in such work re-creates and reinforces the distance between a white speaker who introduces, or frames, the tale and the African American narrator who tells it, as well as the distance between the African American narrator and the predominantly white audience. Almost invariably, tales in the plantation tradition portray former slaves as longing for the old plantation days and characterize them as submissive and childlike. The use of black dialect that was endemic to stories of the plantation tradition and in minstrel shows became in many white minds inextricable from reality and accepted as symptomatic of black inferiority. This powerful and persistent image has resulted in serious critiques of African American literary dialect as depicted by white authors, including Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, Ambrose Gonzales of South Carolina, and Faulkner, with some scholars charging these authors with resorting to stereotype to portray black speech, while others defend the authenticity of their dialectal representations.

Associations with minstrelsy and the plantation tradition led many black writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to avoid representations of dialectal speech in their work, with Chesnutt being a notable exception. His “conjure tales” of the 1880s and 1890s mimic the formal conventions of the plantation tradition while subverting its goals and themes by indirectly condemning slavery and criticizing southern racial relations, all in the guise of the plantation tradition. Chesnutt’s narrator, Julius McAdoo, a former slave, recounts tragic tales of slavery days in a dialect designed to disguise or otherwise make palatable the subversive nature of the stories to their white audience. For example, when Julius’s white employer, John, responds skeptically to a story by Julius highlighting the need for white “masters” to be tolerant and fair and asks if he has made it up, Julius responds, “No, suh, I heared dat tale befo’ you er Mis’ Annie [John’s wife] dere wuz bawn, suh. My mammy tol’ me dat tale w’en I wa’n’t mo’d’n knee-high ter a hopper-grass.” A similar exception was Zora Neale Hurston, who re-created the speech and rich oral traditions of close-knit African American communities in Florida in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). However, several of Hurston’s African American contemporaries, most famously Richard Wright, railed against her representations, arguing that her work perpetuated the stereotypes established and maintained by the plantation tradition and minstrelsy.

The tradition of representing southern speech in literature continues into the 21st century. Contemporary writers of fiction and poetry, including Alice Walker of Georgia, Pat Conroy of South Carolina, Lee Smith of Virginia and North Carolina, Sonia Sanchez of Alabama, Denise Giardina of West Virginia, and James Alan McPherson of Georgia, draw from the rich linguistic traditions of their home regions, while playwrights such as Suzan-Lori Parks of Kentucky and Shay Young-blood of Georgia bring contemporary southern speech to the stage and to new audiences. Literary dialect remains important to students of southern language and culture because the attempts by authors, whether to reproduce realistic speech or to differentiate characters by means of their dialect, offer meaningful information about southern life and the artistic representations of it. It can reveal how older forms of speech and language, as well as popularly held attitudes toward southern varieties of American speech, change over time, as reflected in the literary dialect of texts and in how audiences and critics respond to it.

LISA COHEN MINNICK

Western Michigan University

Cynthia Goldin Bernstein, ed., The Text and Beyond: Essays in Literary Linguistics (1994); Walter Blair and Raven I. McDavid Jr., eds., The Mirth of a Nation: America’s Great Dialect Humor (1983); Hennig Cohen and William B. Dillingham, eds., Humor of the Old Southwest (3d ed., 1994); Sumner Ives, in Tulane Studies in English (1950); Gavin Jones, Strange Talk: The Politics of Dialect Literature in Gilded Age America (1999); Lisa Cohen Minnick, Dialect and Dichotomy: Literary Representations of African American Speech (2004); Michael North, The Dialect of Modernism: Race, Language, and Twentieth-Century Literature (1994).

McDavid, Raven I., Jr.

(1911–1984) LINGUIST.

Raven Ioor McDavid Jr. was born and raised in Greenville, S.C. He graduated from Furman University in 1931 and received his Ph.D. in English in 1935 from Duke University, with a dissertation on the political thought of John Milton. In 1937 he attended a summer linguistic institute at the urging of his commandant at the Citadel military academy, his first teaching position.(The commandant thought that McDavid, because of his heavy southern accent, needed remedial training in elocution.) He was selected as a model informant for a dialectology class at the institute, was intrigued with what he heard there, and proceeded to become the foremost student of southern speech—and of American English more generally—of his time.

McDavid entered the field of linguistics just at the point of its rapid development as a modern academic discipline. After his initial spark and further institute training, he embarked on a survey of South Carolina for Hans Kurath’s American Linguistic Atlas Project. World War II intervened, but after working in the Army Language Section during the war, McDavid became Kurath’s chief field-worker. During the next 15 years he spent a great deal of his time in the field with informants from Ontario to Florida; he eventually completed more than 500 interviews (averaging six to eight hours each), a record unmatched by any other American dialectologist. At the same time McDavid wrote prolifically, including landmark articles, his abridgement of H. L. Mencken’s The American Language (1963), and, with Hans Kurath, a volume that still serves as a standard reference, The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States (1961).

Raven I. McDavid Jr., a groundbreaking dialectologist who believed that contemporary speech was a product of the cultural circumstances of its speakers, of their social and economic life, and of the historical development of that life (Bill Kretzschmar, photographer, archive of the Linguistic Atlas Project, University of Georgia)

His first major academic appointment was at Case Western Reserve University in 1952. In 1957 he moved to the University of Chicago, the institution with which he was most closely identified. In 1964 McDavid succeeded Kurath as editor in chief of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States, and in 1975 he accepted responsibility for the Linguistic Atlas of the North-Central States. He directed editorial work on both projects until his death in 1984. Recognition came late for McDavid, but in time he won major funding for his atlas projects from the National Endowment for the Humanities and received honorary degrees from Furman, Duke, and the Sorbonne. The Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States began appearing in print in 1980 from the University of Chicago Press. The university’s Joseph Regenstein Library produced microfilm copies of the Basic Materials volumes from the North-Central and Middle and South Atlantic atlas projects.

McDavid’s experience in the field shaped his thought. He always insisted on the importance for linguistics of primary data, of real speech by real people, as opposed to rarefied theory. He believed that contemporary speech was a product of the cultural circumstances of its speakers, of their social and economic life, and of the historical development of that life, and that an accurate understanding of our speech-ways could have a positive effect on the well-being of all members of society.

These ideas made McDavid a primary force in the development of socio-linguistics. His first landmark article, “Postvocalic /-r/ in South Carolina: A Social Analysis” (1948), shows a mature handling of the complex correlations between South Carolina culture and speakers’ pronunciation of /r/ after vowels. Another benchmark, “The Relationship of the Speech of American Negroes to the Speech of Whites” (1951; written with Virginia G. McDavid), provided a corrective to common misapprehensions about the speech of African Americans long before Black English became a popular research area in sociolinguistics. McDavid was in the vanguard of those examining the effects of population movements and urbanization upon our speech, and, in an effort to carry benefits from dialectology to a wide audience, McDavid also promoted applications of his research, especially for the public schools. McDavid studied the speech of all regions of the United States but never forgot his roots in the South: his extensive bibliography is studded with both technical and popular essays such as “The Position of the Charleston Dialect” (1955), “Changing Patterns of Southern Dialects” (1970), and “Prejudice and Pride: Linguistic Acceptability in South Carolina” (1977; written with Raymond K. O’Cain).

WILLIAM A. KRETZSCHMAR JR.

University of Georgia

Anwar Dil, ed., Varieties of American English: Essays by Raven I. McDavid Jr. (1980); William A. Kretzschmar Jr., ed., Dialects in Culture: Essays in General Dialectology by Raven I. McDavid Jr. (1979); Raven I. McDavid et al., eds., Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States, fascicles 1 and 2 (1980, 1982); H. L. Mencken, The American Language, ed. R. McDavid (1963).

Narrative