Five _____________________________________________________________

The Republican Southern Strategy: A Case Study of the Reciprocal Campaign

DURING THE SECOND televised debate in the 1960 presidential election, moderator Alvin Spivlak asked Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon, “Mr. Vice President, you have accused Senator Kennedy of avoiding the civil rights issue when he has been in the South, and he has accused you of the same thing. With both North and South listening and watching, would you sum up your intentions in the field of civil rights if you become president.” Nixon responded with a lengthy defense of civil rights, including his support of government action to ensure fair treatment in employment and education and offering his support for lunch-counter sit-ins:

I have talked to Negro mothers, I’ve heard them explain—try to explain—how they tell their children how they can go into a store and buy a loaf of bread but then can’t go into that store and sit at the counter and get a Coca Cola. This is wrong and we have to do something about it. … Why do I talk every time I’m in the South on civil rights? Not because I’m preaching to the people of the South because this isn’t just a Southern problem. It’s a Northern problem and a Western problem. It’s a problem for all of us.1

Nixon’s pro–civil rights response is especially notable because he is more frequently remembered for promising to slow the pace of civil rights as part of the Republican “southern strategy” to recruit southern white Democrats to the Republican Party. In a 1968 televised interview in the South, for instance, Nixon argued that federal efforts to enforce school desegregation “are going too far. … and in many cases … should be rescinded.”2 Did Nixon change his rhetoric on racial issues as a deliberate campaign strategy aimed at driving a wedge in the traditional Democratic coalition? Moreover, did this change in campaign rhetoric influence voter decision making?

In this chapter, we examine the Republican southern strategy as a case study of our expectations about the interaction of candidates, voters, and campaign dynamics. The Republican use of racial issues to appeal to conservative white Democrats is perhaps the most widely recognized example of a wedge campaign tactic, thus making it a natural case for closer examination of our theoretical arguments. With qualitative analysis of candidate strategy, we are able to explore the link between the preferences of swing voters and the candidates’ decision to use wedge issues. In addition, a quantitative analysis of voter behavior allows us to evaluate the role of the campaign in shaping when and if persuadable partisans were willing to defect to the opposing candidate at the ballot box.

This chapter also offers a careful look at the use of wedge issues prior to the contemporary hyperinformation environment examined in the next chapter. Compared to the information available to campaign strategists today, candidates in the 1960s and 1970s largely had to infer the policy preferences of voters based on region, race, or other broad characteristics, so that strategic policy decisions were made on this rather imprecise information. Likewise, candidates’ campaign messages were primarily communicated through broadcast television or stump speeches, so that message targeting was much less precise than we see today. And stump speeches were often covered by the national press, making it more difficult to communicate unique messages to different audiences and inevitably making wedge issues part of the national campaign dialogue. Thus, given the blunt nature of campaign targeting during this era, candidates faced clear electoral tradeoffs in staking a particular position on a divisive policy, and such tradeoffs were often explicitly discussed as part of the candidates’ strategic planning during the campaign.

A great deal has been written about the Republican southern strategy and we make no attempt to provide a complete chronology here.3 We begin this chapter with a brief historical examination of the origins of and motivations behind the southern strategy, but then focus our attention on empirically evaluating how changes in GOP campaign rhetoric influenced white Democratic voters, and particularly white Democrats who embraced issue positions at odds with their national party. Thus, we analyze both the extent to which Republican campaign strategies were based on reaching cross-pressured Democratic voters and the effect of emphasizing wedge issues on their voting behavior.

By most accounts, the Republican southern strategy was successful. After losing nearly all of the southern states to the Democrats in 1960, Richard Nixon returned to carry five of eleven southern states in 1968 and won each and every Confederate state in his lopsided 1972 presidential victory. The Republicans’ improved showing across the South is often taken as evidence that the southern strategy was effective at winning over southern Democrats. For many observers, the twelve years between Nixon’s loss in 1960 and his landslide victory in 1972 represented the beginning and end of the transformation of the once solidly Democratic South to the current GOP stronghold.4 Much of the rich literature on southern politics focuses on the partisan realignment of the South during this time period, as the conservative South switched allegiances from the Democratic to the Republican Party.5 But even as the South gradually realigned partisan loyalties, Republican candidates still encountered many yellow-dog Democrats (voters who would rather vote for an old yellow dog than a Republican). And many of these otherwise strong Democratic supporters held positions on issues of race that were inconsistent with the policy positions of the Democratic Party. Our analysis leverages changes in campaign content across election years to examine how these inconsistencies between party affiliation and issue attitudes interacted with the campaign environment to shape voter decision making.

We also consider changes in candidate strategy over time. One of the perverse realities of American politics is that once a group’s vote becomes predictable, candidates have less incentive to offer policy rewards to win them over.6 The policy interests of groups fully aligned with one party are more likely to be taken for granted as candidates focus attention on the persuadable voters. Once racially conservative Democrats realigned to the Republican Party, the Republicans shifted their focus to a new group of potential swing voters: socially conservative Democrats.7 Thus, we also trace this transition in the changing rhetoric of the Republican presidential campaigns as well as in the behavior of the electorate.

At the outset, we want to recognize some of the limitations of our analysis. While our interest is in tracing the relative effect of racial and cultural issues over time, racial issues were not the only, or even the most important, issue in the presidential elections covered by our analysis. General economic-and foreign-policy issues, in particular, are almost always the centerpiece of presidential campaigns. By focusing on the patterns and trends over time, we necessarily lose a more complete picture of each individual presidential contest. Also, because our analysis is focused on the attitudes and behaviors of white Democrats, we give only cursory attention to the vote decisions of Republicans and Independents (the results for these groups are mentioned briefly in footnotes). Our analysis also does not touch on the rich public opinion literature examining the nuances of racial attitudes. For instance, we measure the extent to which white Democrats are cross-pressured on racial policies, but do not consider whether those policy conflicts are rooted in antiblack prejudices, group identities, or conservative ideologies.8 In addition, when we examine the ability of presidential campaigns to prime racial cross-pressures, we do not consider the possible difference in the effects of implicit and explicit racial campaign messages.9 During this time period, the line between implicit and explicit messages is especially blurry. While many scholars argue that campaign communications about crime and welfare contain implicit racial messages, we focus here on explicitly racial policies, such as segregation, busing, affirmative action, and the like.

Finally, our analysis in this chapter is not meant to suggest that Republicans alone use wedge issues. Democrats have a long history of emphasizing issues for strategic reasons as well. In our view, all candidates are rational actors seeking electoral victory, so the policy promises of candidates of both parties are shaped by the preferences of voters considered pivotal in building a winning electoral coalition. Indeed, a brief historical look challenges any notion that Democrats took a pro–civil rights position by dint of moral superiority; rather, their position taking on civil rights is also traceable to electoral considerations.

Democrats Set the Stage on Civil Rights

After the end of Reconstruction, southern white hostility toward the Republican Party translated into a cohesive and consistent Democratic voting pattern that continued for nearly a century. In 1928 Herbert Hoover was the first Republican presidential candidate to make inroads in the South, winning Florida, Texas, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee by campaigning on prohibition and anti-Catholic sentiment.10 Looking to expand the Republican presence in the South, Hoover pushed to make a “lily-white” GOP by replacing black patronage hires with white Protestants, but these expansion efforts were derailed by the Great Depression.11 The Great Depression solidified the Democratic stronghold among southern whites, but it also brought northern enfranchised African Americans into Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, breaking their long-standing loyalty to the “Party of Lincoln.” Before the 1936 election, Pittsburgh publisher Robert Vann advised fellow black voters, “My friends, go turn Lincoln’s picture to the wall. That debt has been paid in full.”12

Yet, as the 1948 election approached, it was unclear if Truman could hold together this uneasy Democratic coalition. Truman’s approval ratings were at an all-time low and Republicans had captured control of both houses of Congress in the midterm election. As Truman developed his campaign strategy, his advisors concluded that black voters could prove pivotal in the election. One of Truman’s advisors, special counsel Clark Clifford, argued forcefully that the African American vote would be crucial to the ultimate success of the Truman campaign:

A theory of many professional politicians is that the northern Negro voter today holds the balance of power in Presidential elections for the simple arithmetical reason that the Negroes not only vote in a bloc but are geographically concentrated in the pivotal, large and closely contested electoral states such as New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan. … [The Negro] is just about convinced today that he can better his present economic lot by swinging his vote in a solid bloc to the Republicans. … To counteract this trend, the Democratic Party can point only to the obvious—that the really great improvement in the economic lot of the Negro of the North has come in the last sixteen years only because of the sympathy and policies of a Democratic Administration. The trouble is that this has worn a bit thin with the passage of the years. … Unless there are new and real efforts … the Negro bloc, which, certainly in Illinois and probably in New York and Ohio, does hold the balance of power, will go Republican.13

The campaign strategy memo went on to predict that Republicans would use legislation to appeal to the black swing voters,

In all probability, Republican strategy at the next session will be to offer a [Fair Employment Practices Commission], an anti-poll tax bill, and an anti-lynching bill. This will be accompanied by a flourish of oratory devoted to the Civil Rights of various groups of our citizens. The Administration would make a grave error if we permitted the Republicans to get away with this. It would appear to be sound strategy to have the President go as far as he feels he must possibly go in recommending measures to protect the rights of minority groups. This course of action would obviously cause difficulty with our Southern friends but that is the lesser of two evils.14

It seems that a clear strategic calculation was made on the basis of electoral interests to stake a pro–civil rights stance. Truman’s advisors assumed that southern whites would remain loyal to the Democratic Party even if their presidential candidate appealed to black voters. The strategy memo bluntly declared, “As always, the South can be considered safely Democratic. And in formulating national policy, it can be safely ignored.”

President Truman appeared to follow the strategy laid out by his advisor. On February 2, 1948, Truman sent a message to Congress asking for civil rights legislation and outlined a specific list of policy objectives. On July 26 he issued two executive orders. One instituted fair employment practices in the civilian agencies of the federal government; the other provided for “equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”

In hindsight, it was a political miscalculation to take the South for granted. In protest of the pro–civil rights agenda, Strom Thurmond walked out of the 1948 Democratic convention and ran for the presidency as a segregationist. Truman narrowly won the White House, but he laid bare the deep fractures in the Democratic Party coalition over the issue of civil rights. Many years later, presidential advisor Clark Clifford acknowledged this miscalculation, “We did not realize how quickly Southern whites would abandon the President if he supported equal civil rights for all Americans.”15

Truman’s campaign strategy for the 1948 presidential election highlights the importance of pivotal voters in shaping the policy agenda of presidential candidates. His decision also placed the national Democratic Party squarely in the pro–civil rights camp. In making the first move on this divisive issue, Democrats placed the ball in the Republicans’ court. They now had the choice either to exacerbate the fracture in the Democratic Party by taking the polar position of the Democrats, or to neutralize the issue by taking the same position.

Republican Position Taking on Civil Rights

As the minority party, Republicans had little choice but to appeal to traditional Democratic voters if they wanted to capture the White House. Since the New Deal, the majority of the American public has affiliated with the Democratic Party. Measures of party identification from the NES cumulative file finds as few as 29 percent of the public identified themselves as Republicans during the mid-twentieth century. The Eisenhower victories of the 1950s, however, demonstrated that it was possible for a Republican candidate to pull voters away from the New Deal coalition, and Republican Party leaders openly debated how they could best attract voters from the Democratic camp. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, northeastern Republicans, led by Nelson Rockefeller, pushed for a “city strategy” that included appealing to northern blacks and the growing numbers of registered black voters in the South. Opposing this strategy were western Republicans who argued that gains could be made among white southern Democrats.16

Throughout the 1950s, candidates from both parties battled for the black vote. Before the 1956 election, Democrat Hubert Humphrey warned, “Unless we do something constructive and take a firm forward step [on civil rights] our party is going to suffer at the ballot boxes. … Our Republican friends know they are not going to get votes in the South, so they’re pushing hard for [black] voters in the North.”17 Eisenhower attracted 39 percent of the black vote in 1956, and there were projections that Republicans could improve on that share in the 1960 election. It was, after all, a Republican Supreme Court that struck down the separate-but-equal doctrine and a Republican president who mobilized federal troops against a Democratic governor in Little Rock. Republicans had also routinely cosponsored pro–civil rights legislation in Congress.

Thus, in the run-up to the 1960 presidential election, two things were clear. First, there was a divisive racial cleavage between northern and southern Democrats that was ripe for exploiting. Second, the number and political importance of enfranchised blacks had increased. As Journalist Theodore White explained, “Since the northward migration of the Negro from the south, the Negro vote, in any close election, has become critical in carrying six of the eight most populous states of the union. To ignore the Negro vote and Negro insistence on civil rights must either be an act of absolute folly—or one of absolute calculation.”18

Some scholars have argued that Republicans’ decision to take a conservative position on civil rights in the 1960s was driven not by electoral concerns, but rather, by an ideological struggle between conservative and liberal party leaders.19 After all, there had long been clashes between northeastern liberal Republicans like Nelson Rockefeller and western conservative Republicans like Barry Goldwater across a number of policy domains. Since Richard Nixon was the Republican nominee in 1960, 1968, and 1972, we have the opportunity to look for changes in campaign strategy and rhetoric used by the same individual, reducing the likelihood that any changes were due to pure ideological considerations. We thus compare the party platforms, campaign speeches, and campaign strategy memos across these election years to determine if Nixon’s position taking on racial issues was grounded in electoral or ideological considerations.

Nixon’s Strategy in the 1960 Election

With the Democratic Party wedded to a pro–civil rights position, the question facing Richard Nixon was whether his campaign strategy would appeal to southern whites or northern blacks. In The Making of the President 1960, Theodore White concludes that “it lay in Nixon’s power to reorient the Republican Party toward an axis of Northern-Southern conservatives. His alone was the choice. … Nixon made his choice, I believe, more out of conscience than out of strategy.”20 Although it is of course difficult to directly assess the motivations behind a candidate’s decision making on policy issues, there were also indications that Nixon believed the civil rights actions of the late 1950s would lead to higher levels of black enfranchisement that would benefit the Republican Party.21 In a letter to Richard Nixon, Martin Luther King Jr. estimated that the Civil Rights Act of 1957 would create 2 million new black voters who would vote Republican if the GOP continued to support civil rights.22 The 1960 Republican Party platform made reference to this expected growth in black voters in the South, stating, “The new law will soon make it possible for thousands and thousands of Negroes previously disenfranchised to vote.” Incidentally, the 1960 election also corresponded to the decennial population census, which had documented a tremendous growth in the number of northern blacks.

Nixon’s pro–civil rights rhetoric was particularly pronounced early in the campaign. During the 1960 Republican National Convention, it was Nixon who personally pushed hard to court northern blacks by being indistinguishable from the Democratic Party on civil rights policies. According to Theodore White’s firsthand account,

The original draft plank prepared by the platform committee was a moderate one: it avoided any outright declaration of support for Negro sit-in strikes and Southern lunch counters and omitted any promise of federal intervention to secure Negroes full job equality—both of which the Democrats, at Los Angeles had promised. … On Monday, July 25th, it is almost certain, it lay in Nixon’s power to reorient the Republican Party toward an axis of Northern-Southern conservatives. Nixon insisted that the platform committee substitute for the moderate position on civil rights (which probably would have won him the election) the advanced Rockefeller position on civil rights.23

In his nomination acceptance speech, Nixon went further, proclaiming that “for those millions of Americans who are still denied equality of rights and opportunity, I say there shall be the greatest progress in human rights since the days of Lincoln, 100 years ago.” As he campaigned in the South, Nixon began his stump speeches with a defense of his civil rights position, “I have my convictions, you have yours, but together, we must move forward to solve it. … We must not continue to have a situation exist where Mr. Khrushchev … is able to point the finger at us and say that we are denying rights to our people.”24

Nixon had credibility on civil rights issues—he was a member of the NAACP and as vice-president had been the administration spokesperson on civil rights.25 One journalist commented that Nixon was the “spearhead of the Republican efforts to capture a larger share of the Negro vote in 1958 and 1960.”26 Indeed, Nixon’s pro–civil rights background was not lost on the Kennedy campaign, which in its Counterattack Sourcebook, a confidential campaign strategy book, listed Nixon’s NAACP membership as a point for attacking Nixon in the South.27

Nixon’s policy agenda on civil rights appeared to reflect those votes Nixon considered pivotal to the election outcome and in 1960, those votes included northern blacks. Theodore White reports that both candidates decided that the “swing states” were California, New York, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Michigan (with Kennedy also considering Massachusetts and New Jersey pivotal states). In each case, these swing states had sizable black populations.28 Nixon’s campaign strategy was also reflected in his vice-presidential selection of Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., a former Massachusetts senator with a liberal record on civil rights. The first African American to serve in a White House administration, E. Frederick Morrow, was among a select group of advisors who attended a secret midnight caucus at the Republican National Convention in 1960 to discuss Nixon’s vice-presidential selection. When asked his choice, Morrow recommended Lodge because he felt “not even the NAACP can be against his superb liberal record.”29

To be sure, Nixon still tried to appeal to southern voters on other issues, especially later in the campaign when he realized Kennedy did not have a lock on the South, but Nixon’s campaign agenda on civil rights in 1960 appeared to be particularly concerned with appealing to (or at least retaining support of) black voters.30

Nixon lost the 1960 election in one of the closest presidential contests in American history. Moreover, despite Nixon’s efforts to reach African American voters, he received less support from the black community than Eisenhower only four years earlier.31 With this loss, many Republicans, including Nixon, appeared to reassess their electoral strategy. In a 1961 speech to southern GOP leaders in Atlanta, Republican Senator Barry Goldwater verbalized what would come to be known as the “southern strategy”—“We’re not going to get the Negro vote as a bloc in 1964 and 1968, so we ought to go hunting where the ducks are.” Theodore White summed up this perspective: “[L]et us give the Northern Negro vote to the Democrats, and we shall take the Old South for ourselves.”32

The Republican National Committee initiated “Operation Dixie” in 1957 to build on Eisenhower’s gains in the South, but they stepped up those efforts after Nixon’s loss. Conservative journalist Robert Novak reported his observations from a conference of state party chairmen in 1963, “A good many, perhaps a majority of the party’s leaders, envisioned substantial political gold to be mined in the racial crisis by becoming in fact, though not in name, the White Man’s Party. ‘Remember,’ one astute party worker said quietly over the breakfast table one morning, ‘this isn’t South Africa. The white man outnumbers the Negro 9 to 1 in this country.’”33

Goldwater’s extreme conservatism and states’ rights platform in 1964 contributed to a thumping at the polls, but it also highlighted the fact that southern whites were willing not only to abstain from voting for the Democratic candidate (as they did in 1948), but were also willing to vote Republican. The 1964 election made clear that southern whites would go to the Republicans if the candidate offered a conservative policy position on civil rights. In South Carolina, political strategist Harry S. Dent, then political advisor to Senator Strom Thurmond, reportedly rejoiced following Goldwater’s defeat in 1964, “In the next two years, the seeds of the Republican southern strategy began to sprout and grow. … The Tree was bearing fruit. … We South Carolina Republicans were now getting ready for the big coup—the White House—with this new Southern Strategy.”34 It wasn’t just the Republicans who foresaw the electoral playing field shifting. President Johnson lamented to one of his aides that the Civil Rights Act had probably “delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.”35

In the run-up to the 1968 election, debate continued about the Republican Party position on civil rights. The Ripon Society, founded in 1962 and named after Ripon, Wisconsin, the birthplace of the Republican Party, continued to push for a pro–civil rights position. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the Ripon Society produced several strategy reports outlining how they believed the GOP could become the majority party by reaching out to minority voters. For example, a 1968 report argued that the GOP should explicitly denounce policy positions that might alienate moderates and minority voters: “This is the direction the party must take if it is to win the confidence of the ‘new Americans’ who are not at home in the politics of another generation … [like] the moderate of the new South—who represent the hope for peaceful racial adjustment and who are insulted by a racist appeal more fitting another generation. These [policies] and others like them hold the key to the future of our politics.”36

In 1968 Nixon would once again win the Republican presidential nomination. Given his previous pro–civil rights platform, it was initially unclear how Nixon would position himself on racial issues. A Time magazine article predicted that “Ronald Reagan is probably the only Republican capable of consolidating his party’s arduous—and still tenuous—risorgimento in Dixie.”37 Yet, as soon became clear, Nixon shifted his electoral strategy from a northern, urban focus to one concentrated on the South (especially the rim South). In his memoirs, Nixon writes,

I would not concede the Carolinas, Florida, Virginia, or any of the states of the rim of the South. These states became the foundation of my strategy; added to the states that I expected to win in the Midwest, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Far West, they would put me over the top and into the White House. My polls showed that Wallace’s vote was over-whelmingly Democratic but that when his name was not included in the poll sampling, his votes came to me on more than a two-to-one basis, especially in the South. … A major theme that we used very effectively in key states such as Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia was that Wallace couldn’t win.38

And the calculation was that the southern voters were particularly concerned about racial policies. A memo from advisor Harry Dent to the newly elected Nixon made clear, “So far as Southern politics is concerned, the Nixon administration will be judged from the beginning on the manner in which the school desegregation guidelines problem is handled. Other issues are important in the South but are dwarfed somewhat by comparison.”39

Some historians have traced Nixon’s decision to switch from courting northern blacks to southern whites to a meeting with Strom Thurmond in an Atlanta hotel room in early 1968. According to Reg Murphy and Hal Guliver, authors of The Southern Strategy, Nixon made a deal:

The essential Nixon bargain was simply this: If I’m president of the United States, I’ll find a way to ease up on the federal pressures forcing school desegregation—or any other kind of desegregation. Whatever the exact words or phrasing, this was how the Nixon commitment was understood by Thurmond and other southern GOP strategists. In 1968 Strom Thurmond, once the darling of the third-party Dixiecrat movement of two decades before, would campaign for Nixon in the Deep South, doing all he could to undercut the third-party movement of former Alabama Governor George Corley Wallace, the most successful third-party presidential drive in more than half a century. Wallace simply could not win, Thurmond insisted, as attractive as Wallace’s segregationist views might seem. But Nixon—that was something else again. Nixon, Thurmond suggested, really held views much closer to Wallace than it might appear.40

The seeds of change for Nixon’s 1968 position shift on racial issues, however, were planted during his failed 1960 presidential bid. In a December 15, 1960, meeting following his narrow defeat, Vice President Nixon, outgoing President Dwight Eisenhower, and GOP chairman Thruston Morton discussed the lessons of the 1960 presidential election. Hinting at the southern strategy to come, Nixon commented that Lodge’s campaign promise to appoint a Negro to a Nixon cabinet “just killed us in the South.” On the subject at hand, Eisenhower pointed out that “we have made civil rights a main part of our effort these past eight years but have lost Negro support instead of increasing it.” Nixon responded that “we discovered as far as this particular vote is concerned it is a bought vote, and it isn’t bought by civil rights.” To this, Senator Morton offers his full agreement “and, as far as he was concerned, ‘the hell with them.’” 41 In 1968 and 1972 we see this strategic shift in civil rights position taking in Nixon’s campaign rhetoric.

Nixon Strategy in 1968 and 1972

With Nixon’s shift in perspective from viewing northern blacks as the critical swing voters to viewing southern whites as necessary for victory, Nixon’s rhetoric on civil rights also underwent a substantial transformation.

In 1960 Nixon had fought to insert a 1,250-word civil rights plank in the party platform declaring that “civil rights is a responsibility not only of states and localities; it is a national problem and a national responsibility. … We favor the enactment and just enforcement of such Federal legislation as may be necessary to maintain this right at all times in every part of this Republic.” Such language directly addressed the “states’ rights” argument of civil rights opponents. In contrast, the 1968 platform made little reference to civil rights and promised “decisive action to quell civil disorder, relying primarily on state and local governments to deal with these conditions.” In contrast to the explicit support expressed for counter sit-ins and the “vigorous support of court orders for school desegregation” found in the 1960 Republican Party platform, the 1968 platform asserted that “America has adequate peaceful and lawful means for achieving even fundamental social change if the people wish it.” Whereas Nixon’s 1960 platform pledged “vigorous support of court orders for school desegregation,” in the 1968 (and 1972) campaign Nixon made clear his opposition to “forced integration,” school busing, and affirmative action.

As was also the case in 1960, Nixon’s electoral calculation about the strategically important persuadable voters was reflected in his selection of a vice-presidential running mate. In 1968 Nixon selected Maryland governor Spiro Agnew, who was recognized for his appeal to Democrats. Nixon explained that “Agnew fit the bill perfectly with the strategy we had devised for the November election. With George Wallace in the race, I could not hope to sweep the South. It was absolutely necessary, therefore, to win the entire rimland of the South.”42 Journalists called Agnew the “chief agent of the President’s Southern Strategy” in the 1968 campaign. At an event in Mississippi, for instance, Agnew declared, “The principles of most of the people of Mississippi are the principles of the Republican Party.”43

Nixon’s change in campaign rhetoric from 1960 to 1968 is also apparent in his stump speeches in the South. Not only did Nixon spend more of his time campaigning in the South and border states, he also now emphasized his affection for and allegiance to the region:

[M]ore than any recent American presidents I perhaps have a closer affinity to the South because of my education. I took my law degree at Duke University. … I learned a lot about law and I learned also a lot about this nation’s background, and the differences, and I learned some of the things I had thought were right when I got there might not be right. … [W]hen I went to Duke University in 1934, after a very good college education at Whittier in California, I was utterly convinced that Ulysses S. Grant was the best general produced on either side in the Civil War. After rooming for years with Bill Perdue of Macon, Georgia, I found, and was almost convinced by Bill Perdue’s constant hammering on it, that Ulysses S. Grant would be lucky to be about fourth behind Robert E. Lee, Joseph Johnston, and Stonewall Jackson.44

Nixon’s switch on racial policies is also apparent in the reactions of political elites to his candidacy and campaign promises. In 1960 Nixon garnered the praise of Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP, for his “good record on civil rights.”45 By 1972 Nixon’s campaign positions earned the scorn of the very same NAACP leader. The New York Times reported, “In some of the strongest language he has ever used in referring to any President, Roy Wilkins yesterday condemned Richard Nixon as one who is ‘with the enemies of little black children’ … Mr. Wilkins accused President Nixon of turning back the clock on integration.”46

These changes in Nixon’s rhetoric on issues related to race and his change in targeted voters, suggest that his campaign strategy reflected a switch from viewing blacks as an important electoral voting bloc in 1960 to viewing racially conservative white Democrats as the more critical swing vote in 1968 and 1972. Nixon presidential advisor Kevin Phillips argued in The Emerging Republican Majority, a book that Newsweek called the “political bible of the Nixon era,” that GOP efforts to reach minority voters were not reaping rewards and greater benefits would be secured by reaching out to persuadable Democrats. According to Phillips, “for all their advocacy of programs aimed at the Negro vote, liberal establishment Republicans, like Nelson Rockefeller, Jacob Javitts, and John Lindsay proved unable to induce sizable numbers of Negros to vote for them.”47 The Republican’s electoral fortunes rested on “turning [the South] into an important presidential base of the Republican Party.”48

Thus, rather than focusing Republican campaign efforts heavily in northeastern states, as they did in 1960, Nixon and the GOP shifted efforts South. In notes from a meeting with the president, Nixon chief of staff H. R. Haldeman makes clear the new focus on the South: “South terribly important … look at whole spectrum of So[uth] gains [in] ’60 vs. ’70, that’s where the ducks are. Sh[ou]ld give NO credence to Ripon Society bull. … Ducks are in the mountains and the So[uth]” (emphasis in original).49 Similarly, in a memo titled “The President’s Developing Image in the South” sent from Harry Dent shortly after the 1968 election, Dent referenced Nixon’s efforts in the South stating,

I digested every word the president said in the [1968] campaign. This was used, after editing by the New York office, to effectively assist in carrying five crucial states—Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Virginia—in addition to countering the Wallace vote in other states. … I also believe we must look to the South politically to further develop the two-party system, get new Congressmen and Congressional control, win Southern Congressional support for the Nixon program, and to insure re-election in 1972.

Nixon’s handwriting on the memo requested that it be circulated to John Mitchell, Nixon’s campaign manager.50

Critically, Nixon was targeting not the hard-core Republicans, but the persuadable Democrats and Independents—those who disagreed with the Democratic Party’s position on racial policies. In 1972 campaign advisor Patrick Buchanan argued in a memo sent to President Nixon and other campaign advisors:

[W]e should schedule RN into the “undecided” arenas, union halls, Columbus Day activities, Knights of Columbus meetings, etc. We should keep in mind that there is only—at most—20 percent of the electorate that will decide this, not who wins, but whether or not it is a landslide, and quite frankly, that 20 percent is not a principally Republican vote. Perhaps RN has to make appearances at GOP rallies—but when he does, he is not going where the ducks are.51

Referencing southern Democrats, in particular, Harry Dent sent news of the Nixon administration’s policy goals and its potential impact on the persuadable Democrats, “The administration is moving toward reform, decentralization, and reorganization as per the campaign statements of 1968. … The President’s new welfare reform program should prove to be quite a political boon to the South. … If this is handled properly, you ought to be able to get some traditional Democrat votes loosened up.”52

In 1972 the Nixon campaign actively sought the support of Democratic voters who had supported segregationist George Wallace. While working on plans to publicize the number of “Democrats for Nixon,” GOP campaign worker Mickey Gardner wrote to Pat Buchanan on July 17, 1972, about an important development in their plans for courting southern Democrats:

Bill Franz, President of NASCAR, and a key Wallace supporter … feels that the time is right for a nearly “complete” defection of the Wallace Campaign structure to the re-election effort of Richard Nixon. This defection would be, in fact, simply a shift from Wallace to Nixon. … [P]rompt action could result in a pro-Nixon re-election resolution coming out of the Independent Party convention in a few weeks.53

By no means are we the first to observe that Nixon’s campaign agenda reflected a strategic decision to appeal to policy-conflicted Democrats. An impressive historical analysis by Paul Frymer and John David Skrentny similarly concludes that “the decision making process [of the Nixon administration] was … directly shaped by the ability of various groups to claim themselves as potential swing-voters and for the party to find these groups compatible with both important elements of the existing electoral coalition and with other crucial swing groups in national elections.”54 Historian James Reichley writes

To what extent was Nixon motivated by conviction in his handling of the busing issue, and to what extent by political expediency? … Nixon dug in hard against any remedy that would cause even mild concern among the southern, suburban and white working class constituencies that he aimed to win by large majorities in 1972. It would be hard not to conclude that his judgment was heavily influenced by his immediate political interests.55

It seems clear that Nixon’s position taking on racial policy issues reflected strategic considerations about the potentially persuadable voters in the electorate rather than his ideological convictions alone. The remaining question is whether or not these campaign efforts to prime racial issues influenced voter decision making.

The Influence of the Southern Strategy on Voters

While Nixon clearly changed his racial campaign rhetoric from 1960 to 1968, it is not clear if such changes were successful in attracting southern white Democrats. Certainly, aggregate vote returns suggest that Nixon’s southern strategy was successful. In 1960 Nixon won only Florida and the border states of Tennessee, Virginia, and Kentucky. In 1972 he won every southern state and in most cases he won by over-whelming margins—exceeding the victory margins of nearly any other state in the country. Of course, aggregate voting returns do not conclusively demonstrate that Nixon was successful at priming racial policy preferences among the targeted voters. To gain a better view of the individual-level dynamics of the southern strategy, we turn to an evaluation of racial priming efforts on the decision-making process of individual voters, especially those cross-pressured Democrats who were the target of Nixon’s racially conservative appeals.

In order to compare the effects of this wedge strategy, we examine the influence of racial policy incongruence on the presidential vote choice of white Democrats across different campaign contexts.56 We expect that Democrats who were incongruent on racial issues would be more likely to defect when the campaign emphasized the racial policy differences between the candidates. We first compare individual-level behavior in 1960 and 1968—years in which the Republican candidate was constant but campaign rhetoric on racial issues was quite different—using the open-ended likes/dislikes questions from the American National Election Studies. We then take advantage of the NES 1972–76 panel study to evaluate changes in decision making among the same respondents in two very different campaign contexts. Finally, we use the NES cumulative file to trace the evolution and influence of changing GOP electoral strategies from 1964 through 2004, as they transitioned from a focus on racial policies to the contemporary emphasis on “moral” wedge issues.

A content analysis of New York Times campaign coverage shows that racial issues constituted roughly 16 percent of news coverage of domestic policy issues in 1960 and 22 percent in 1968.57 Similarly, a content analysis of Nixon’s campaign speeches in 1960 reveals that just over 10.3 percent of his stump speeches referenced racial issues compared to 22.4 percent of his speeches in 1968.58 More importantly, the candidates not only increased attention to racial policies, they offered distinct alternatives in 1968 compared to 1960. A wedge strategy can work only to the extent that the candidates take different policy positions. When the campaign highlights the key differences between the candidates, the voters are able to vote on the basis of those differences.59 To be sure, things on the ground were also changing during this time period. In 1960 the civil rights movement was relatively new; by 1968 Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated, urban riots had erupted across the country, and tensions were high both within the black community and between whites and blacks. Nixon’s change in rhetoric on racial issues between 1960 and 1968 reflected a change in the group of voters he viewed as persuadable, a calculation that no doubt was influenced by this changing political environment.

In order to evaluate whether there was a corresponding change in the effect of racial cross-pressures on voting behavior, we rely on the NES open-ended questions that asked respondents if there was anything they liked/disliked about the political parties and candidates.60 The advantage of this measure is that a volunteered response is more likely to capture an important issue preference and, therefore, a meaningful tension between party affiliation and issue preference.61 The disadvantage is that there are somewhat higher levels of nonresponse, so that the sample sizes for some subgroups (especially white southerners) are quite small. Even more regrettably, the open-ended questions were asked of only half of the NES sample in 1972, preventing a comparable analysis of the open-ended questions in the 1972 presidential election.

Looking first at the extent of racial policy incongruence in these two election years, we see in table 5.1 that the majority of surveyed Democrats volunteered that they disliked something about the Democratic Party (or the candidate), although relatively few mentioned racial policy issues. As a percentage of the policy issues mentioned, however, racial policies accounted for more than one-third of the issue-based disagreements volunteered.62 Interestingly, in the South, the percentage of white Democrats mentioning a racial cross-pressure was actually higher in 1960 than in 1968. At the 1960 Democratic convention, southern Democrats had strongly opposed the national Democratic Party’s platform on civil and voting rights. Critically, though, we do not expect that this opposition should influence defection because Nixon matched the Democrat’s position in 1960. In her diary about the Democratic National Convention in 1960, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the South’s opposition to the civil rights plank: “As usual, the Southern people threatened that the Democratic Party would lose their states in the November election. One wonders where these states will go if they leave the Democratic Party.”63 Indeed, in Mississippi and Alabama, fourteen unpledged Democratic electors won election from the voters. By 1968 it became clear that those unhappy southern Democrats would go to the Republican camp if the candidate took a more favorable position on the issue. The proportion of Democrats in the South had also declined from 66 percent of the southern populace in 1960 to 58 percent by 1968, suggesting some of those racially cross-pressured Democrats may have changed their partisan affiliation by 1968.

TABLE 5.1 Volunteered Racial Cross-pressures among White Democrats in 1960 and 1968 | |||||||

Percent All |

Percent Non-South |

Percent South | |||||

1960 |

1968 |

1960 |

1968 |

1960 |

1968 | ||

Any Cross-pressure |

67.4 |

75.1 |

62.6 |

74.0 |

78.9 |

77.8 | |

Racial Cross-pressure |

5.4 |

5.4 |

1.0 |

4.3 |

15.6 |

8.4 | |

Note: Table shows that southern white Democrats were more likely to volunteer a racial policy dislike about their party than northern white Democrats. Data source is the American National Election Study cumulative file.

The key question, however, is whether or not there is a relationship between racial policy incongruence and an individual’s decision to defect. We estimate the effect of racial cross-pressures on a white Democrat’s decision to vote for the Republican nominee, controlling for other factors that may influence the likelihood of defection, including age, education, gender, and strength of party identification.64 The model results, including coefficients, standard errors, model fit, and Wald estimates for the cross-pressure variable are reported in appendix 3.

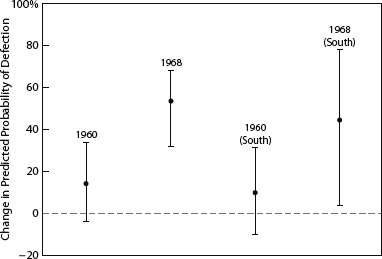

To evaluate the priming effects, we compare the effect of racial cross-pressures across years. In figure 5.1, we see that racial cross-pressures among white Democrats predicted support for Nixon in 1968, but not 1960. In 1960 Democrats who disagreed with the national party position on civil rights and other racial issues were no more likely to support Nixon than those not cross-pressured. In 1968, in contrast, these cross-pressured Democrats had a 58 percent probability of defecting to Nixon. In other words, racially conservative Democrats were more likely to vote Republican than Democratic.65 These findings are supportive of our expectation that the decision for a persuadable partisan to defect depends on the issue content of the campaign. When candidates offered distinct issue positions on racial issues in 1968 and the issue was emphasized in the campaign, racial policy conflicts weighed more heavily in the vote decisions of incongruent Democrats. This is true even though the extent of policy incongruence remained stable or even declined (among southern Democrats) from 1960 to 1968.

Figure 5.1: Effect of Racial Cross-pressures on Predicted Probability of Defection, 1960 and 1968

Note: Figure shows racial cross-pressures were related to Democratic defections to Nixon in 1968, but not 1960. Shown is the difference in the predicted probability of defection for a racially cross-pressured white Democrat compared to a racially consistent, white Democrat, holding constant other variables in the model. A Wald test rejects the null hypothesis of equal coefficients across elections for the national sample. Data source is the American National Election Study cumulative file.

Without considering variation in candidate positions and campaign dialogue across elections, existing research may provide an incomplete picture of the relationships between campaigns, issues, and voting behavior. For instance, pooling elections into a single decade, Byron Shafer and Richard Johnston find very little change in the relationship between racial attitudes and presidential voting between the 1950s and 1960s.66 Yet, our analysis suggests that this relationship varies across different election years depending on the extent to which racial attitudes were central to the campaign. By ignoring the fact that voters’ conflicting predispositions shape responsiveness to political campaigns, studies of campaign influence miss the ways in which campaigns affect the decision to defect. If elites take divergent positions on issues and emphasize those issues in their campaigns, cross-pressured partisans are likely to weigh these inconsistent positions more heavily in their vote choice.

A potential alternative explanation for our conclusion is that the direction of causality is reversed. That is, support for a candidate, in this case for Nixon in 1968, influenced the policy position that voters adopted, rather than the other way around. As discussed in the previous chapter, some scholars have argued that voters may bring their policy preferences in line with those held by their preferred political candidate.67 The standard argument is that policy preferences are fleeting reflections of candidate preference and that candidate choice is determined by more long-standing party attachments. But our focus on policy preferences that conflict with party attachments belies this logic—clearly, party identification was not the determinant of vote choice among those who voted for the opposition party candidate. In addition, the use of volunteered policy disagreements makes it more likely that we have captured genuine policy attitudes that are in disagreement with voters’ preferred political party.

Moreover, by most indications conservative preferences of racial policies predated elite campaign efforts, especially in the South.68 In the 1956 NES, 19 percent of white southerners volunteered a racial issue as something they disliked about one of the two major parties in contrast to just 3 percent of white northerners. In 1958, 33 percent of white southerners disagreed with the statement, “If Negroes are not getting fair treatment in jobs and housing, the government should see to it that they do” (compared to 16 percent of white northerners). These conservative racial preferences came at a time when the parties were not taking appreciably different positions on racial issues, suggesting that these preferences were more likely to be the determinant of, not the result of, candidate preferences. To more directly address this potential concern, we turn to an additional test of our hypothesis using the National Election Study’s 1972–1976 panel study. With repeated inter-views of the same individuals in two distinct campaign contexts, we are able to examine the extent to which racial attitudes—in this case, opinions on school busing—remain stable during this four-year time period. We can then evaluate the influence of being incongruent on this issue in an election in which the issue was a source of considerable debate in the campaign, compared to one in which it was not.

Comparing the Effects of the Busing Issue in 1972 and 1976

In contrast to his 1960 campaign efforts, Nixon attempted to prime racially conservative attitudes among white Democrats during the 1968 and 1972 campaigns. In 1972 his rhetoric was particularly focused on the issue of busing to achieve racial integration of public schools. According to Joseph Aistrup, Nixon’s “plans were to structure his appeal around support for the idea of civil rights, but opposition to its active enforcement. … Nixon’s metaphor symbolizing this struggle over the intermediate color line was the battle over busing.”69 In developing his campaign strategy for the 1972 campaign, his advisors viewed busing as a potential wedge issue because Democrat George McGovern was supportive of busing, while many rank-and-file Democrats were opposed. In a campaign strategy memo titled the “Assault Book,” Nixon advisor Patrick Buchanan wrote, “It can be stated, flatly, that George McGovern supports both ‘forced busing’ and the concept of racial balance (a statistical quota system) in every public school in the United States. … This entire albatross, either as a whole or independently, can be publicly hung around the neck of the Democratic candidate.”70

To establish his opposition to busing, early in the 1972 campaign season—corresponding with George Wallace’s announcement that he would seek the Democratic nomination—Nixon placed the issue center stage by requesting that Congress place a moratorium on busing. The Republican platform also emphasized the issue, stating that “we are irrevocably opposed to busing. … [W]e regard it as unnecessary, counter productive and wrong.” Reinforcing our contention that candidate position taking is shaped by information about the preferences of the public, Nixon referenced his efforts to gauge public opinion on the issue during the 1972 election. Campaigning in the South, Nixon noted,

I was looking at some polls recently. … [D]id you know that busing is a much hotter issue in Michigan today than it is in Alabama? Now, what does that mean? It does not mean that the majority of the people in Michigan are racist, any more than the majority of the people of Alabama, because they happen to be opposed to busing. It simply means this: it means parents in Michigan, like parents in Alabama and parents in Georgia and parents all over this country, want better education for their children, and that better education is going to come in the schools that are closer to home and not those clear across town.71

In contrast, four years later presidential candidate Gerald Ford mentioned busing only once in his stump speeches.72 Following President Nixon’s resignation in 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal, the 1976 presidential campaign focused on issues of government reform rather than racial policies. Indeed, racial issues were mentioned in less than 4 percent of Ford’s campaign speeches compared to more than 10 percent of Nixon’s speeches in 1972.73 A comparison of New York Times campaign coverage indicates that there were 610 articles referencing the busing debate from January 1 through Election Day in 1972 compared to just 244 articles during the same time period in 1976. Compared to Nixon’s presidential campaign rhetoric in 1972, Ford did very little to appeal to racially cross-pressured Democrats in 1976.

Why did the issue of busing drop out of campaign rhetoric from 1972 to 1976? Some scholars have attributed the change to Ford’s lack of “southern political acumen.” From this perspective, Ford was simply unwilling to exploit racial issues for electoral gain. Joseph Aistrup concludes that “Gerald Ford, whose Republican roots were firmly within the Rockefeller-Scranton wing of the party, did not possess the political will to politicize racial issues in the 1976 presidential contest. … Rather, Ford ran a campaign against federal spending and reminded voters that he had restored integrity to the White House.”74

Although we cannot speak to Ford’s personal convictions on racial issues, we would expect the change in his campaign agenda if the candidate determined a different group of voters would be pivotal. Internal memos from Ford’s campaign suggest that Ford made a strategic decision to try to build a winning coalition outside the South. After a lunch with conservative journalist George Will, a staff assistant sent a note to President Ford mentioning that “Will suggested that Ford might write-off the South and capitalize on the anti-Carter feeling [in] the West and Northeast.”75 Similarly, in a lengthy memo from campaign advisor Michael Duval, the Ford campaign reached the same conclusion, recommending that Ford target “maximum” resources to the large swing states in the northern industrial belt. According to the report, “The first decision is whether to concentrate total effort on the northern industrial states from New Jersey to Wisconsin, plus California, or to devote some effort to peripheral southern states, plus California. … We recommend concentration on the northern industrial states” (italics added).76 These calculations were no doubt made based on the strengths and weaknesses of both Ford and Carter and the broader political environment. Either way, they had implications for Ford’s issue agenda.

Although the particular policy messages were different, Ford’s strategy continued to appeal to cross-pressured partisans and Independents on wedge issues. Duval’s memo offers a clear link between the preferences of persuadable Democrats and Independents and the campaign agenda:

To build a winning coalition in the swing states, the president must build on his base of rural and small town majorities with suburban independents and ticket splitters. … In very general terms, the target constituency in the suburbs for the President is the upper blue collar and white collar workers. … These are independent minded voters, many of whom are Catholic. In addition, there is a weakness in Carter’s support among Catholics and also among Jews. … Jewish skepticism of Carter as a Southern fundamentalist provides an opportunity to strip away part of the traditional Democratic coalition.

The memo goes on to recommend a specific policy agenda designed to appeal to these persuadable voters (italicized phrases are those President Ford highlighted with marks in the margin):

The swing constituency is concerned about the following issues: 1. National Defense—This group favors national defense. … The president is well positioned on these issues, but the articulation of his policies has been insufficient. … 2. Morality … This group also wants to feel that the country is moving again, after Vietnam, Watergate, and the recession. … 3. Economy and Taxes—These issues are of major concern and the President’s record is excellent. But public awareness of the President’s policy on tax reduction and the effect on the taxpayer of the Democrat’s economic policy need more effective communication. … 4. Crime … the President must come down hard on the issue. His programs will work and they make sense. (However, we must be careful not to turn the gun lobby against us. …) 5. Education … The President must show awareness and concern on this issue above and beyond the busing question. … 6. Quality of life—The vast majority of the swing voters who live in the suburbs are conservationists and strongly supportive of a responsible environmental policy. In this issue area, the President is perceived by many as a pro-business, anti-environment candidate. To correct this situation, we must become actively involved in the energy and recreation areas.77

In nearly two hundred pages of campaign strategy documents, busing received only a cursory mention—other issues were clearly believed to be more critical for winning over persuadable voters in targeted states. Once the campaign decided to focus on swing voters in northeastern states, the media strategy presented by Bailey, Deardourff, and Eyre, Inc., made a similar recommendation about the campaign issue agenda:

In many of the target States, where Democrats and Independents are needed to win, the most serious problem a Republican candidate has is the perception of Republicans in general as hard-nosed, big-business types—against the working people, against the poor people, against minorities. President Ford has to break the Republican stereotype. … One way to show compassion is in his treatment of the issues. … [I]t is important that he express strong feelings, and take a leadership position, on such matters as the Equal Rights Amendment, black opportunity, the plight of the Indians, and the hardships of older people. In the northern industrial States, Republicans are seldom successful unless their words and a few strong “people” stands make them more popular than their Party.78

Late in the campaign, after polling found that Ford might have a shot at picking up states in the South, Ford added some southern stops on the campaign trail. But advisors David Gergen and Jerry Jones reminded Ford that his appeals in the South must still keep his target constituency in mind, “You do not want to appear to be kowtowing to the South and especially to perceived Southern prejudices. If your supporters in Philadelphia find you stressing very conservative Southern themes, they could easily be alienated. Instead of identifying yourself with strictly Southern interests, what you want to do is identify interests of the South with the interests of the entire nation—interests that you deeply share.”79 The memo continued on to recommend that Ford focus on holding down government spending, the size of government, taxes, costs of living, and maintaining a strong national defense.

So, whereas President Nixon strategically chose to emphasize the issue of busing to appeal to incongruent Democrats in the South in 1972, President Ford focused on other issues in appealing to a different subset of incongruent Democrats in the Northeast in 1976. The positions of the candidates were also somewhat less distinct in 1976 than in 1972. Although the 1976 Republican Party platform affirmed that “we oppose forced busing” and the Democratic Party platform endorsed “mandatory transportation,” Jimmy Carter generally tried to avoid talking about the issue. The contrasting campaign agendas in the two election years allow us again to compare the effects of racial cross-pressures in 1972 when the issue was highlighted and in 1976 when the issue was not emphasized.80

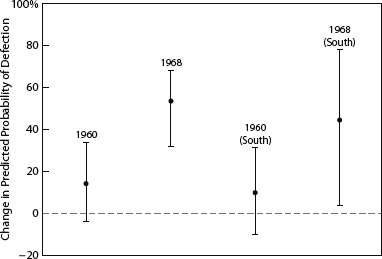

Despite the variation in attention to racial issues during these campaigns, it is important to note that the extent of policy incongruence among white Democrats did not dramatically change during this time. Polls found that, in the aggregate, the majority of white Democrats were opposed to busing in both 1972 and in 1976. More importantly, individual-level attitudes on the issue were quite stable. Looking at respondent opinions in the NES panel, we find that 85 percent of white Democrats had consistent attitudes on busing—either supportive of busing or opposed to busing in both waves of the study.81 As shown in figure 5.2, 57 percent of white Democrats and 70 percent of southern white Democrats indicated that they preferred to “keep children in neighborhood schools,” rather than support busing in both waves of the 1972–76 panel study.82 On the other side of the aisle, Republicans in the electorate also opposed busing, so it was a particularly attractive wedge issue: 67 percent of Republicans and 56 percent of Independents indicated that they preferred to “keep children in neighborhood schools” in both waves of the survey. Clearly, Nixon could emphasize his opposition to busing among Democrats without fear of generating substantial opposition among his own party members or among Independents.

Figure 5.2: Attitudes toward School Busing in 1972 and 1976

Note: Figure shows that the majority of white respondents held stable, conservative attitudes on the issue of busing in both 1972 and 1976. Data source is the American National Election Study 1972–1976 panel.

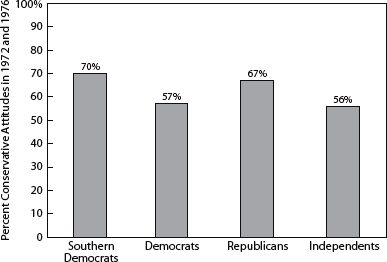

Restricting our analysis to only those individuals with stable opinions (and stable partisan identification) allows us to compare the influence of these attitudes on presidential vote choice in 1972 and 1976 with less concern that the observed relationship reflects projection or learning effects. Reported in figure 5.3 are the substantive effects of being conflicted about the busing issue on the probability of defecting to the Republican candidate in 1972 and in 1976. Reported is the difference in the predicted probability of defecting to the Republican president between cross-pressured Democrats and those congruent on the busing issue.83 In 1972 a cross-pressured Democrat was 35 percentage points more likely to defect than a congruent Democrat, but in 1976 there was no difference in the probability of defection between these two groups. These results suggest that racial cross-pressures played a much greater role in voters’ decision making in 1972 when it was a focus of the campaign discourse, compared to 1976 when, although the candidates’ positions and the public attitudes had not changed, the campaign no longer made the issue salient.84

So, whether we use open-ended responses from 1960 and 1968, or closed-ended questions and panel respondents from 1972 and 1976, we find that the effect of racial cross-pressures on voter decision making depends on campaign context. Although we cannot conclusively state that results are attributable directly or exclusively to campaign messages alone, the evidence is supportive of our hypothesis that the effect of cross-pressures on vote choice very much depends on the candidates’ campaign agendas.

Of course, our analysis cannot untangle the candidates’ efforts from the broader political context and media dialogue. There is little doubt that the external environment shapes both the campaign strategy of the candidates, and the voters’ priorities, and that it shapes the extent to which a campaign message will resonate or not.85 Even still, the historical evidence suggests that both Nixon and Ford were responsive to the attitudes of targeted voters in developing their issue agendas.

Racial and Moral Issues in the Evolution of the “Southern Strategy”

Next we turn to a broader longitudinal analysis that considers the evolution of the original GOP “southern strategy,” as it moved to incorporate cultural or moral issues. Using the closed-ended questions from the NES cumulative file, we estimate the relative effects of racial and moral cross-pressures across election years.

Figure 5.3: Effect of Racial Cross-pressures on Predicted Probability of Defection, 1972 and 1976

Note: Figure indicates that the effect of being cross-pressured on the issue of busing is statistically significant in 1972, but not 1976. Shown is the difference in the predicted probability of defection for cross-pressured Democrats compared to consistent Democrats, holding constant other variables in the model. A Wald test rejects the null hypothesis of equal coefficients across elections. Data source is the American National Election Study 1972–1976 panel.

Why would the original southern strategy need to change? Perhaps because of its success. The GOP’s emphasis on racial conservatism appealed to many white Democrats, but gradually some of those racially conservative Democrats realigned to the Republican Party.86 While scholars disagree over the exact causes of the transformation of the once solidly Democratic South to the current stronghold of the GOP, the result was that by the end of the 1980s, Republican presidential candidates could reliably count on substantial support among southern voters.87 As the party coalitions changed, so too did the potential cleavages available to Republican candidates. Explicitly emphasizing racial issues during campaigns also increasingly risked violating the American norm of equality, and was earning the Republican Party the reputation of racial insensitivity. Many scholars and journalists have argued that Ronald Reagan strategically moved away from explicit racial appeals and instead implicitly primed negative racial predispositions among white voters by emphasizing issues like welfare and crime.88 In The Race Card, Tali Mendelberg argues that “racial appeals did not disappear; they were transformed, often consciously and strategically.”89 In a much-quoted interview about the use of racial campaign appeals, Reagan’s political advisor Lee Atwater, explained the evolution of the Republican southern strategy,

As to the whole Southern strategy that Harry Dent and others put together in 1968, opposition to the Voting Rights Act would have been a central part of keeping the South. Now [a candidate] doesn’t have to do that. All you have to do to keep the South is for Reagan to run in place on the issues he’s campaigned on since 1964 … and that’s fiscal conservatism, balancing the budget, cut taxes, you know, the whole cluster. … You start out in 1954 by saying “nigger, nigger, nigger.” By 1968 you can’t say “nigger”—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, “we want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “nigger, nigger.”90

Certainly by the 1990s, following reactions to the infamous “Willie Horton” ad during the 1988 presidential election, many Republicans worried about a backlash among new groups of swing voters they were hoping to court, especially women.91 The national Republican Party, for instance, quickly distanced itself from former KKK member David Duke when he ran for governor on the Republican ticket, and Republican Senator Trent Lott was forced to step down as majority leader after saying that the country would have been better off had Strom Thurmond won the 1948 election.92 In 2005 Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman apologized to the NAACP for the GOP’s southern strategy saying, “Some Republicans gave up on winning the African American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarization. I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong.”93

To be sure, many white Americans continue to hold conservative racial policy preferences. The 2004 NES indicates that most white Democrats support the Republican Party position on affirmative action.94 Likewise, state-level ballot initiatives banning affirmative action in employment, education, and public-contracting decisions have easily won electoral support. But with the realignment of many racially conservative Democrats to the Republican Party, and with the increased potential for a backlash, Republicans have turned their attention to other potentially persuadable voters. Discussing the 1984 Reagan electoral strategy, Atwater explained that “we must remember the fundamentals of Southern politics with an electorate divided into three groups: country clubbers (Republican), populists (‘usually Democratic: will swing to the GOP under the right circumstances’), and blacks (Democratic). … We must assemble coalitions in every Southern state largely based on the country clubbers and the populists.”95 In his memoirs, Richard Nixon explained that “the Republican counterstrategy was clear. … We should aim our strategy primarily at disaffected Democrats, and blue-collar workers, and at working-class white ethnics. We should set out to capture the vote of the forty-seven-year-old Dayton housewife.”96

GOP strategists decided that cultural issues could potentially bridge the country clubbers and populists. The abortion debate, the quickly rising divorce rate, and other societal problems brought attention to issues that continue to split Democrats in the contemporary American electorate. Attempting to reach socially conservative Democrats, Republican candidates began to emphasize social issues like school prayer, flag burning, pornography, and gay rights. The motivation behind a campaign emphasis on such issues was confirmed by Chris Henick, the RNC’s southern political director during the late 1980s, who explained that linking Dukakis and the Democrats to “opposition to certain anti-pornography laws and to prayer in the schools provide ideal ‘wedge issues’ to encourage moderate-to-conservative Democrats to abandon their party.”97 In his 1988 nomination speech, George H. W. Bush ran through a litany of wedge issues that might divide the traditional Democratic coalition:

Should public school teachers be required to lead our children in the pledge of allegiance? My opponent says no—and I say yes. Should society be allowed to impose the death penalty on those who commit crimes of extraordinary cruelty and violence? My opponent says no—but I say yes. And should our children have the right to say a voluntary prayer, or even observe a moment of silence in the schools? My opponent says no—but I say yes. And should, should free men and women have the right to own a gun to protect their home? My opponent says no—but I say yes. And is it right to believe in the sanctity of life and protect the lives of innocent children? My opponent says no—but I say yes.98

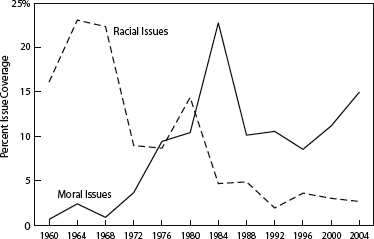

A content analysis of campaign news coverage by the New York Times, shown in figure 5.4, indicates the increasing focus on moral issues in presidential elections as news coverage of racial issues declined.99 Beginning in 1984 the percentage of articles discussing morality outnumbered the percentage of articles addressing race—and the focus on moral issues continued through the 2004 presidential contest.

Perhaps ironically, cultural issues are now the primary issues on which Republican candidates attempt to appeal to minority voters. For example, in the 2000 election, candidate George W. Bush emphasized policies like faith-based initiatives and school vouchers when he spoke to African American audiences. At a conference held by the National Urban League during the 2004 presidential contest, President Bush encouraged the predominantly black audience to consider voting Republican: “If you believe the institutions of marriage and family are worth defending and need defending today, [then] take a look at my agenda.” Following a round of applause, President Bush continued, “If you believe in building a culture of life in America, take a look at my agenda.”100

Figure 5.4: Racial and Moral Issues as Percentage of Campaign News Coverage

Note: Figure shows the percent of New York Times general election campaign coverage devoted to racial and moral issues, 1960–2004. Data provided by Lee Sigelman and Emmett Buell.

The Effects of Racial and Moral Cross-pressures over Time

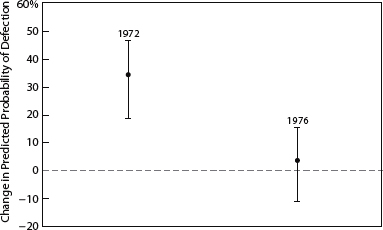

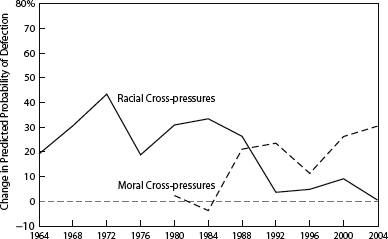

To examine the role of racial and moral cross-pressures over time, we rely on the closed-ended policy questions in the NES cumulative file. We again estimate the substantive effect of racial and moral cross-pressures on the probability that a Democrat voted for the Republican presidential candidate in each of the last eleven presidential campaigns, reported in figure 5.5.101 These results follow the general pattern that we would expect given the strategic campaign decisions we have discussed throughout this chapter. Those who are highly cross-pressured on racial issues were much more likely to defect in the 1960s–1980s, compared to those not cross-pressured, while racial policy incongruence has little impact in recent years. In contrast, Democrats highly cross-pressured on social issues, like abortion, were more likely to defect in recent years compared to the 1980s (when questions were first asked). It was with the 1992 presidential election that the effect of moral cross-pressures exceeded the effect of racial cross-pressures, perhaps reflecting the prominence of moral criticisms of then-candidate Bill Clinton.

Figure 5.5: Effect of Racial and Moral Cross-pressures on the Predicted Probability of Defection, 1964–2004

Note: Figure indicates that the impact of racial cross-pressures has declined in recent years, while the impact of moral cross-pressures has increased. Reported is the change in the predicted probability of defection between highly cross-pressured white Democrats and congruent Democrats, holding constant all other variables in the model. Data source is the American National Election Study cumulative file.

There is little doubt that race was central to the early transformation of the South, but the importance of race in American attitudes and behavior in the later part of the twentieth century has been a topic of considerable debate. Some scholars have argued that racial issues no longer explain voting behavior by the 1970s, while others contend it remains an important predictor of vote choice.102 Alan Abramowitz concludes, for instance, that “attitudes toward racial issues had a negligible impact on voting decisions” by the late 1980s.103 Our findings suggest that the extent to which voters weighed racial policies in their vote decisions has depended on the particular campaign context. When presidential candidates took divergent positions on questions of race and were willing to emphasize those differences in their campaigns, voters’ racial attitudes played a stronger role in their decision-making processes. In recent elections, Republican candidates have been more likely to focus their strategic efforts on winning over culturally conservative Democrats, and we see those efforts reflected in the behavior of Democrats who face inconsistent policy positions on social and moral issues.

Conclusion: Civil Rights and the Reciprocal Campaign

To win a presidential election, candidates must build a coalition between their base supporters and persuadable voters. Throughout this book, we have argued that candidates look for wedge issues that will divide the potential winning coalition of the opposition party and will appeal to groups of swing voters. The Republican southern strategy is a classic example. We have made the case that Richard Nixon strategically emphasized conservative racial policies in his 1968 and 1972 presidential campaigns because he perceived the persuadable voters to be racially conservative Democrats, especially in the South. In contrast, Nixon in 1960 and Ford in 1976 viewed other groups as swing voters and adjusted their issue agendas accordingly.