Six _____________________________________________________________

Candidate Strategy in the 2004 Campaign

IN HIS NOMINATION ACCEPTANCE SPEECH at the 1988 Republican National Convention in New Orleans, President George H. W. Bush made his now famous pledge:

I’m the one who will not raise taxes. My opponent now says he’ll raise them as a last resort, or a third resort. But when a politician talks like that, you know that’s one resort he’ll be checking into. My opponent, my opponent won’t rule out raising taxes. But I will. The Congress will push me to raise taxes and I’ll say no. And they’ll push, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push again, and I’ll say, to them, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” (italics added)1

Bush would later find it impossible to make good on that promise. Facing an economic recession, a congressional mandate to reduce the deficit, and a Democratic Congress that opposed cuts to entitlement programs, Bush had little room to maneuver. In a press release in June 1990, Bush explained, “It is clear to me that both the size of the deficit problem and the need for a package that can be enacted require all of the following: entitlement and mandatory program reform, tax revenue increases, growth incentives, discretionary spending reductions, orderly reductions in defense expenditures, and budget process reform.” Bush broke his campaign promise.

Many argued that Bush’s reversal on taxes contributed to his electoral defeat in 1992. Pat Buchanan threw his hat into the Republican primary, explaining, “We Republicans can no longer say it is all the liberals’ fault. It was not some liberal Democrat who said ’Read my lips: no new taxes,’ then broke his word to cut a seedy backroom budget deal with the big spenders on Capitol Hill.”2 Democratic television ads replayed a clip of Bush’s pledge, labeling him untrustworthy and unprincipled. Although a number of other prominent Republicans agreed that a tax increase was necessary, Bush was criticized because he reneged on a campaign promise. Republican pollster Richard Wirthlin called Bush’s pledge “the six most destructive words in the history of presidential politics.”3 Political consultant Ed Rollins called it “the most serious violation of any political pledge anybody has ever made.”4

As Bush’s experience so clearly illustrates, there are appreciable risks associated with staking out a position on a political issue. Once in office, the policy stance can tie the hands of an elected official, limiting policy-making options. Candidates who later change their position are labeled “flip-floppers” or “wafflers.” Concerned about such negative consequences, it is understandable why politicians work aggressively to carry out their campaign agendas after winning office. In general, scholars find a strong relationship between campaign policy promises and government policy agendas after an election.5

But it is also risky to take a stand on a policy issue because of the potential for alienating voters who disagree. Richard Nixon, for instance, recognized that opposing civil rights policies might win votes among white southerners, but that it would also cost votes among blacks. Candidates must consider both the gains and losses that come with staking a position on a divisive policy issue. For these reasons, it has long been thought that rational candidates will avoid taking stances on policy issues in a political campaign.6

Yet, despite the incentives to avoid controversial issues, presidential candidates do make policy promises. Candidates routinely outline their policy agendas in their nomination acceptance speeches, detail their positions on campaign Web sites, and highlight issue priorities in their campaign communications, stump speeches, and media appearances. In every campaign, candidates make choices about which issues to discuss and which to avoid. But political scientists do not have a clear understanding of why candidates emphasize some issues while ignoring or downplaying others. There is broad recognition that candidates try to frame salient issues in a way that advantages their candidacy, but it is less clear why candidates choose particular policy agendas and priorities.7 Charles Franklin laments that “the political nature of elections lies in the choices candidates make about strategy. … As we have become adept at studying voters, it is ironic that we have virtually ignored the study of candidates. Yet it is in candidate behavior that politics intrudes into voting behavior. Without the candidates, there is only the psychology of vote choice and none of the politics.”8 To be sure, there exist a number of rich, descriptive accounts of individual campaigns, but what is lacking is an underlying theory of candidate strategy about issue agendas. And the limited existing research is largely silent about why a candidate might emphasize positional issues in particular.

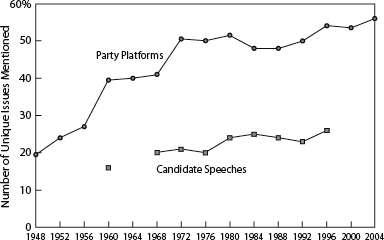

In this chapter, we look more closely at the implications of our arguments for candidate behavior in contemporary presidential campaigns. In particular, we focus on the link between the information environment and campaign strategy. While the Republican southern strategy offered an illustration of the long-standing incentive to use wedge issues, in this chapter we turn to an examination of why and how contemporary candidates narrowly target a wide range of wedge issues. Certainly, candidates today are taking stances on more issues and more divisive issues than ever before. Figure 6.1 traces over time the average number of unique issue positions taken in party platforms and candidate speeches.9 More striking is the fact that presidential candidates in 2004 took positions on more than seventy-five different political issues in their direct-mail communications. Just the sheer number of different issues discussed raises questions about the reasons for such diverse and fragmented issue agendas and about the implications for issue dialogue in the campaign. By examining the volume, content, and targeting of television and direct mail advertising in the 2004 presidential campaign, we are able to evaluate the candidates’ issue strategies. Our findings suggest that information and communication technologies have changed not only how candidates communicate with voters, but also who they communicate with and what they are willing to say, with potentially troublesome implications for political inequality.

Conventional Wisdom about Candidates’ Issue Strategies

Why and how do candidates choose particular campaign issues? To some extent, the issue content of a political campaign is constrained by conditions outside the candidates’ control. When an issue of over-arching national interest is in the limelight, like an economic or foreign-policy crisis, candidates cannot ignore it. Journalists will cover it, debate moderators will press candidates to discuss it, and voters will expect to hear how the candidates will handle it. Candidates are also compelled to address any issues Americans consider to be among the most pressing problems of the day, issues like health care, education, and other valence issues—policies that everyone considers important and laudable, even if they disagree on the means for improvement.10 It is hard to imagine that a credible presidential candidate could campaign without addressing the issues the public identifies as the “most important problems” facing the country.11 But beyond the issues that candidates must discuss, there are those that they choose to emphasize. In addition to responding to the exogenous environment, candidates try to control the issue context of the campaign. Among the topics candidates put on the agenda are “positional” issues—those about which people take different sides—minimum wage, school prayer, and stem cell research.12 But why would rational candidates take stands on such divisive political issues?

Figure 6.1: Growth in the Policy Position Taking of Presidential Candidates, 1948–2004

Note: Figure shows an increase in the unique number of policy positions taken by presidential candidates. Data sources are the U.S. Party Platforms and the Annenberg/Pew Archive of Presidential Campaign Discourse.

The conventional wisdom has been that rational office-seeking candidates will avoid controversial issues or will at least be ambiguous on such issues to avoid offending someone who might disagree. Yet this expectation does not seem to hold up to the empirical reality of contemporary presidential campaigns. More recently, political observers and scholars have suggested that candidates might be willing to take positions on controversial issues as a way of appealing to their core partisan supporters. From this perspective, candidates must invigorate their base with policy promises in order to generate financial contributions, sustain volunteer efforts, and motivate citizens to turn out. For instance, Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson argue that Republican politicians have recently moved away from the center because they are kowtowing to party activists: “What is the great force that pulls Republican politicians to the right? In a word, the ‘base.’ … The base has always had power, but never the kind of power it has today. With money more important in campaigns than ever, the base has money. With the political and organizational resources of ordinary voters in decline, the base is mobilized and well organized.”13 The underlying assumption of this line of reasoning is often that candidates will generally ignore nonbase voters either because they are unlikely to vote or they can be swayed with nonideological campaign appeals.14

In contrast, we suggest that the use of these issues logically follows from the preferences and behaviors of the voters—specifically the cross-pressured partisans who might be receptive to campaign appeals. To reiterate our now familiar empirical and theoretical conclusions thus far, a candidate can win over a persuadable voter by increasing the salience of a cross-cutting issue that provides an advantage over the opponent. In order to make the wedge issue salient, the candidate must stake out a position on the issue that is clearly distinguishable from the positions of the opposition party. And the relative distinctiveness of the two candidates is often clearest on divisive positional issues. The particular policy disagreements that have the potential to be exploited will depend on the broader political environment as well as the characteristics of the opposing candidates, but we expect that vote-seeking candidates will look for strategic opportunities to emphasize wedge issues.

Our expectation that candidates develop their campaign strategy with an eye toward Independents and policy-conflicted partisans fits nicely with some existing political science research about legislative voting behavior. In a study about U.S. Senators, for example, Gerald Wright found that senators’ policy votes more closely reflected the preferences of Independents than the full electorate or even partisan identifiers.15 He concluded that “senators balance their appeals between their own party’s activists and the ideological leanings of the Independents of their states. In this view, the opposition party adherents—at least those that are ideologically in tune with the out-party—are not heeded.”16 Another study concluded that Republican senators lost control of the chamber following the 1986 midterm elections because their policy voting primarily reflected the preferences of their base supporters and was not sufficiently responsive to the policy concerns of Independents and dissident Democrats who had helped elect Ronald Reagan in the previous presidential election.17 Our analysis builds on this research by linking the incentives of presidential candidates to their campaign agendas.

Information Technology and the Microtargeting of Wedge Issues

Presidential candidates have always had incentives to use wedge issues, but today’s information environment has enabled greater use of divisive political issues in presidential campaigns. A candidate’s willingness to use a wedge strategy is influenced by the information available about the electorate and the tactics available to disseminate campaign messages. As illustrated by Bush’s campaign promise on taxes, taking a stand on an issue—even one that enjoys widespread support—carries political risk. The more information candidates have about the preferences of individual voters, the better they can calculate the costs and benefits of emphasizing a particular position. Critically, politicians today have more detailed information about citizen preferences than ever before. As Matthew Dowd, Ron Fournier, and Douglas Sosnick recently observed in Applebee’s America, “If you’re a voter living in one of the 16 states that determined the 2004 election, the Bush team had your name on a spreadsheet with your hobbies and habits, vices and virtues, favorite foods, sports, and vacation venues, and many other facts of your life.”18

This information is combined with communication technologies that allow candidates to microtarget campaign messages; that is, candidates can send a tailored message to a narrow subgroup of the electorate on the basis of information about that subgroup. Microtargeting allows candidates to surgically deliver different messages to different constituencies, thus expanding the arsenal of potential wedge issues that can be used in the campaign. With direct mail, email, telephone calls, text messaging, Web advertising, and the like, candidates can narrowcast issue messages to some voters even if others in their coalition might disagree or consider the issue less important. Microtargeting enables candidates to use double-edged issues. Thus, the campaign tactics that contemporary candidates rely on to communicate with voters ultimately shape the substance of the messages that are communicated. So whatever the impact of microtargeted messages on the voters, this tactic has the potential to influence campaign dynamics by changing the behavior of candidates.

Certainly, there are numerous examples of candidates emphasizing wedge issues even before contemporary communication technologies. In the 1948 presidential election, Harry Truman complained that the Republican strategy was intended to “divide the farmer and the industrial worker—to get them squabbling with each other—so that big business can grasp the balance of power, and take the country over lock, stock and barrel.”19 In previous political eras, however, wedge strategies were more often used when the cleavages within a party coalition were readily apparent and when the issue not only divided the opposition but also created consensus among the candidates’ own supporters. When campaign messages are communicated to a broader audience, candidates have to carefully consider the consequences of taking a stand on a divisive issue. In the 1976 campaign, for instance, President Ford’s strategists acknowledged the difficulty of narrowly targeting strategically important voters. In recommending that the president tailor his campaign activity to different groups, President Ford was advised that “actions to get target constituency groups … should be rifle shots aimed at the specific group involved. These efforts should not be undertaken with the objective of getting national press coverage (although we must keep in mind that this will happen if any mistakes are made).”20

Because of the link between the information environment and the use of wedge issues, our expectations are consistent with candidate polarization trends over time. One of the key puzzles in political science stems from the empirical reality that candidates’ campaign agendas are increasingly divergent from academic predictions that candidates will moderate their policies to appeal to the pivotal voter in the electorate. Considerable research has documented the fact that political elites have grown more polarized across policy issues in recent decades, with candidates taking decidedly distinctive policy positions. Morris Fiorina poses the question, “Whatever happened to the median voter? Rather than attempt to move her ‘off the fence’ or ‘swing’ her from one party to another, today’s campaigners seem to be ignoring her.”21 Previous research has offered a number of different explanations for the recent increase in political polarization, including the realignment of the South, partisan gerrymandering, the greater numbers and influence of interest groups, and growing income inequalities in the electorate.22 We leave to other scholars the important (and difficult) task of sorting through and testing all the proposed catalysts of party polarization. We simply add another potential explanation to the list: information about individual voters.

With the explosion of information about individual voters political communication has become more diverse, fragmented and complex. This changing context influences not only how candidates communicate with citizens, but also who they are contacting and what they are willing to say. Our information-centric perspective on the relationship between candidates and voters in presidential campaigns recognizes that just as changing the information available about the candidates can change the behavior of the voters, so too can changes in the amount, type, or accessibility of information about the voters shape the behavior of the candidates. The information environment helps determine a candidate’s ability and willingness to use a wedge strategy. Candidates should be less willing to stake a position on an issue if they are uncertain about the preferences of voters or if the issue message will be disseminated to voters who disagree with the position. In a game theoretic model, Ed Glaeser, Giacomo Ponzetto, and Jesse Shapiro show that the ability to microtarget messages produces more extreme party platforms.23

We are by no means the first to call attention to the importance of information technology for campaign politics. Political scholars have long recognized that information and communication technologies fundamentally affect how candidates run campaigns. Communication scholars David Swanson and Paolo Mancini observe that

electronic wizardry elongates the campaign day by affording opportunities for candidates, freed from the six o’clock imperative, to make news anytime; it elongates the campaign season and proliferates its cycles by enhancing chances for candidates to build name recognition, establish a voter support base, and raise funds at a campaigner’s pace, not in conformity with short-or long-term media scheduling.24

Scholars have also documented how Web sites, online fund-raising, and email communication have become integral to political campaigns.25 As one report lamented following the 2000 presidential election,

Eighty years ago, radio allowed people to hear candidates by their firesides for the first time. Thirty years later, television added pictures, which transformed even party conventions into events arranged for people to absorb in their living rooms. Videotapes, computers, and direct mail added to the precision. This year, the Internet, with its personal “cookie” technology, joined automated celebrity phone calls, push-poll proselytizing, issue Web sites, and political e-mails to drive politics even further into a personalized, invisible space.“26

Often, however, these new technologies are viewed as a supplemental communication tool for conducting “politics as usual”—presumed to change the style of political campaigns, but not the basic structure of political interaction.27 As one study summarized, the Internet is “nothing more than a new medium in which old patterns of political behavior and information flows are played out anew.”28 In contrast, we argue that information and communication technologies have changed not just how candidates communicate with voters, but also the substance of their communication.

History offers us several examples of this link between the information environment and campaign strategy. For instance, the first mass political party, the Jacksonian Democrats in 1828, could be built from a “patchwork of conflicting interest groups, classes, and factions” because of changes in transportation and communication technologies that allowed Jackson to communicate with and mobilize a far-flung population.29 Likewise, the introduction of radio broadcasting in presidential campaigns changed the style and substance of candidate speeches. In discussing the introduction of radio in the 1924 presidential election, journalist Don Moore observed, “While before candidates spoke mainly to the party faithful, they now had to tailor their speeches more for the undecided, and even the opposition. … Because radio audiences did not feel as if they had to show signs of support for the speaker, the audience became not only bigger, but more heterogeneous. Undecided and opposing voters, who might not be comfortable attending a rally, could easily tune in at home.”30 Whereas the introduction of previous communication technologies, especially television, was used to expand and broaden the audience receiving a campaign message, technologies today are used to more narrowly communicate individualized messages to smaller and more segmented audiences.

In many ways, microtargeting revives the campaign strategy of the late nineteenth century, where whistle-stop campaigns and segmented news markets allowed candidates to communicate different messages to different voters. Based on information about various constituencies from local party leaders, candidates would modify their stump speeches in order to maximize their appeal to whatever group they were currently addressing. In the 1948 presidential campaign, for instance, Harry Truman criticized the Taft-Hartley Act, calling it “a termite, undermining and eating away your legal protection to organize and bargain collectively,” when speaking to a group made up largely of union members in Scranton, Pennsylvania. In contrast, his stump-speech outline for Queens, New York, was marked with the note (in all capital letters), “DO NOT MENTION LABOR OR TAFT-HARTLEY ACT.” Meanwhile, in Dexter, Iowa, Truman declared, “The Democratic Party is fighting the farmer’s battle.”31

Before we analyze the candidates’ strategies on wedge issues in the 2004 presidential election, we first provide a brief history of the campaign tactic of microtargeting. To be sure, the notion that candidates should target specific messages to individual voters is as old as American political campaigns. A Whig-committee campaign memo in 1840 advised that it was the duty of a party subcommittee to “keep a constant watch on the doubtful voters, and have them talked to by those in whom they have the most confidence, and also to place in their hands such documents as will enlighten and influence them.”32

More recently, advisors to President Ford recommended targeting Hispanic voters with special messages by creating “a direct mail program to be developed to special interest groups that are predominantly Spanish-oriented with specific issues (expressed in layman’s language) that would appeal to the particular special interest group (e.g.—day care centers for working mothers to residents residing in low-income housing developments).”33 Although microtargeting as a tactic is not new, changes in the information environment and lessons from commercial marketing, grassroots mobilization, and direct-mail fundraising have made contemporary microtargeting more precise, efficient, and individualized. As we discuss in the conclusion, it remains unclear whether these messages are also more effective. But whatever the influence on voter behavior, we argue that these campaign tactics have had a profound influence on candidate behavior.

In the commercial world, companies began using microtargeted direct marketing in the 1980s as the mass media fragmented and diversified. The proliferation of cable channels, radio, the Internet, and other communication alternatives made it more difficult to reach and influence consumers with television advertising. With the emergence of database-management and data-mining capabilities, advertisers were better able to identify the likes and dislikes of potential customers and could then tailor ads to the individual consumer. Thus, the credit-card offers, catalogs, and other junk mail that clog our mailboxes every day have been personalized, based on our purchasing and lifestyle habits to maximize the likelihood that they catch our attention and interest.

Political candidates observed similar inefficiencies in reaching their intended audiences. As suffrage in the United States expanded and overall voter turnout declined, candidates and parties realized that they needed to more efficiently and strategically use their resources. Candidates have long concentrated resources in those states thought to be most critical to an election outcome. In the first presidential campaign to use television advertising, Dwight Eisenhower purchased spot buys in thirty-nine states, but saturated the airwaves (four to five spots heard by voters each day) in eleven states.34 Later, candidates used precinct voting history and census information about the income or racial composition of a neighborhood for geotargeting, the targeting of efforts to specific precincts and geographic areas in a state that might have a cluster of supporters. For instance, Democratic candidates would concentrate their canvassing in urban precincts where mobilization efforts would be more likely to increase the number of votes for the Democratic candidate. Focusing campaign efforts in a limited number of neighborhoods was more efficient than blanketing an entire state, but it still wasted resources on opposition supporters living in the canvassed neighborhoods and missed potential supporters in other areas. Talking about his experience campaigning for governor of Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis quipped that if he walked up a flight of stairs, he was going to knock on every door—he wasn’t going to skip over an apartment just because a Republican lived there.35

Generally, these geotargeting appeals were more frequently GOTV (get-out-the-vote) messages or broad-based persuasive appeals. Even a demographically homogeneous neighborhood does not guarantee homogeneity in political preferences. Political polling was used to collect information about the preferences of the voters, but given the cost of polling, sample sizes typically allowed for only crude breakdowns by demographic or geographic characteristics. It was risky to talk about divisive issues in geotargeted communications. A campaign strategist for George H. W. Bush explained the geotargeting strategy in the 1988 presidential campaign, “There are some areas where we can play hardball. … Abortion and gun control and going heavy on crime plays in most of the South and most of the West. Where it gets trickier is when we try to go after groups like ethnic Catholics in the North, where the roots to the national Democratic Party are stronger and there are neighborhoods where you mix ethnics with yuppies and every kind of group, so you have to be much more careful.”36 Rather than targeting just state by state, or even neighborhood by neighborhood, candidates today can target household by household. Candidates now know which households to target in a neighborhood and which ones to skip, and candidates can surgically locate the one sympathetic supporter in an otherwise unsympathetic neighborhood.

When available, presidential candidates have always used information about individual voters, but historically such information was available for only a limited subset of voters, such as contributors or volunteers. Using target lists donated, bought, or rented from like-minded candidates or causes, direct-mail fund-raising has been a hallmark of political campaigns since the 1980s. Direct-mail fund-raising was pioneered by Richard Viguerie, the self-proclaimed “funding father” of the conservative movement. In 1965 Viguerie hand-copied the list of twelve thousand individuals who contributed fifty dollars or more to Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. In the forty-plus years since, Viguerie estimates he has mailed out more than 2 billion letters, raising billions of dollars for conservative causes and helping to raise awareness of front-burner conservative issues.37 A candidate’s Rolodex of potential contributors remains one of the most critical elements of a political campaign. Robin Parker, former Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee political director, explained that the very first question asked of a Senate candidate was “who has your lists?”38 She recalled that these limited target lists were often kept on index cards in shoe boxes before the advent of electronic databases. Today, candidates have information not just about contributors but about every voter.

Political parties have created enormous databases that include information about nearly every one of the roughly 168 million registered voters in the United States. With the growth in computing power and information technology, parties and candidates now collect, store, and analyze an overwhelming range of information about individual voters.39 These databases start with voter registration files. Voters’ registration records—including name, home address, voting history, and in many states, party affiliation, phone number, date of birth, and other information—are available to political parties and candidates (twenty-two states have no restrictions on who can access these files).40 The statewide database of 15 million voters in California is available for just thirty-five dollars, for example.41 Several states have put individual voter records online, giving free and open public access. A quick last-name search on the North Carolina State Board of Elections Web site, for instance, pulled up the name, home address, race, gender, party affiliation, polling place, and vote history since 1992 of a colleague at Duke University.

Candidates have been using voter registration rolls, where available, for many years. But until recently there was incredible variability across states in regard to the information collected and the accessibility of that information.42 A few states created electronic files as early as the 1980s, but more often the data were available only as hard copy from the county registrar or municipal jurisdictions, and often included the names of voters long since moved or dead. To build a statewide voter list in Michigan, for instance, candidates had to contact and acquire the voter list from 1,800 different jurisdictions. One consultant noted that these voter registration lists were “barely an improvement over the phone book.”43 States slowly began moving toward computerized registration files following the 1993 National Voter Registration Act. Often called “motor voter,” this legislation required states to allow residents to register to vote when they applied for a driver’s license. In many cases this new law called attention to the poor quality of the registration record systems kept in most states and sparked movement toward electronic files. An additional push in the quality and accessibility of voter information came with the 2002 Help America Vote Act, which mandated states to develop a single, uniform, centralized, interactive voter registration database that would be updated regularly. The majority of states now have easily accessible electronic information on every registered voter.

Although databases start with voter registration files, statistical and computing power have made it possible to match consumer data to individual voter records. Data-management companies such as Equifax, Axciom, Experian, HomeData, D&B, Advo, and ChoicePoint compile individual-level information from myriad sources, both public records and material purchased from other companies. Such databases include names, addresses, address histories, driving record, criminal records, consumer purchases, and a variety of other personal information that allows campaigns access to more information about individual voters than ever before. Increases in computing power and data-storage capabilities, coupled with consumers’ desires for conveniences and discounts, led to a data revolution starting in the 1990s. As explained in a recent account,

Nearly every time a person takes out a loan, uses a credit card, makes an Internet transaction, books a flight, or conducts any of hundreds of other business transactions, he or she leaves a data trail. The average consumer travels through life trailed by thousands of clues to future buying and voting habits, a veritable gold mine for any organization with the money and motivation to solve the mysteries of his or her political attitudes.44

As new information technologies were developing, it became apparent that traditional television campaigning was less effective. In the 1998 congressional races, after years of pouring money into television ads that were increasingly expensive yet less effective, labor unions recommitted money to “ground war” activities—telephone calls, direct mail, and personal canvassing. The decision rested in large part on internal studies of the 1997 New Jersey gubernatorial race that found an 8 percentage-point increase in support for the labor-backed gubernatorial candidate among those contacted compared to those not contacted.45 Such an influence far exceeded any estimates of television advertising effects. Democrats ended up gaining seats in the House in the 1998 election, the first time since 1934 that a president’s party had gained seats in a midterm election. In the 2000 presidential and congressional elections, Democratic candidates once again performed better on Election Day than predicted by preelection polls, which political observers attributed to superior grassroots campaigning.46

In response, Republicans developed a plan to improve their own ground-war efforts, borrowing tactics from the commercial world. Bolstered by academic studies suggesting that nonpartisan GOTV efforts were effective at increasing turnout, as well as changes in campaign finance laws that cracked down on television advertising but left ground-war activities unregulated and undisclosed to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), political will and technological capabilities fully came together for the 2004 presidential campaign. A recent study reports that Kerry campaign staff and volunteers knocked on 8 million doors and made 23.5 million phone calls, while the Bush campaign estimated that their party faithful knocked on 9.1 million doors and made 27.2 million phone calls.47 Importantly, while limited information available about voters once encouraged campaigns to concentrate on GOTV and other mobilization efforts, the expansion of information about voters now allows grassroots efforts to use persuasive appeals.

How has this information influenced campaign strategy and candidates’ issue agendas? With great precision, contemporary candidates are now able to predict the probability that an individual is going to vote, the probability that she is going to vote for a particular candidate, as well as her issue priorities. Ken Mehlman explained, “Basically, what it is, is spending a lot more time IDing people, spending a lot more time figuring out what issues people care about and contacting them on the basis of those issues.”48 Thus, a letter or email highlighting a candidate’s position on the second amendment will be sent to a registered Independent who owns a gun, while a message focused on gay marriage will be sent to a registered Republican who is a member of an evangelical church but has voted sporadically in recent elections. As one political consultant explained, “You don’t have to shotgun anymore. You can now bullet.”49

Alex Gage, Republican consultant and head of TargetPoint consulting, explained step by step how the Republican National Committee translated voter information into campaign strategy.50 First, they obtained the voter registration file from the state with whatever information was included. Second, they appended to the voter file any proprietary data available from the RNC, including previous contributions or membership in like-minded organizations. Third, they merged in consumer data, including magazine subscriptions, mortgage information, credit-card purchases, gun ownership, and the like. Fourth, from this master list, they conducted a survey of roughly 5,500 respondents in the state, asking a variety of questions about political attitudes and behavior including the particular issues that angered or excited the respondents. Based on the survey data, the RNC conducted extensive data-mining studies in order to find out which characteristics predicted a Republican vote. Voters were then segmented into about thirty different groups based on the type of issues that were likely to drive them to vote for Bush, groups like “tax and terrorism moderates” or “religious weak Republicans.” The full database of registered voters was then assigned to one of the segments “based on the lifestyle and political habits he or she shared with those surveyed and already placed in groups.”51

Bush strategist Sara Taylor further explained that individuals in each of these segments were evaluated and ranked based both on their probability of voting and their probability of voting for Bush. The campaign then made strategic decisions about where campaign resources should be spent and what messages should be sent to different individuals. This information was then used to microtarget messages through direct mail, email, telephone calls, and personal visits. Sara Taylor summed it up: “We could identify exactly who should be mailed, on what issues, and who should be ignored completely.”52

These campaign tactics have created incentives for candidates to make explicitly ideological and issue-based appeals to narrower portions of the public. As one consultant explained, “In previous campaigns Republicans would call potential voters with a tape-recorded message from Ronald Reagan or a similar personage on the generic importance of voting. In 2004, a voter concerned about abortion would hear ‘if you don’t come out and vote, the number of abortions next year is going to go up.’”53 This campaign tactic is used to communicate with both base supporters and persuadable voters, but we suggest that microtargeting is particularly significant because it enables the use of wedge issues to appeal to persuadable partisans.

Evaluating Campaign Strategies in 2004

Our analysis will evaluate candidate strategy by comparing the volume and content of messages across mode, source, and recipients. The alternative explanations for candidates’ use of divisive issues—a partisan base versus persuadable voter appeal—have very different observable implications for the patterns of issue content in targeted messages. If candidates are primarily concerned with mobilizing a partisan base, we expect candidate efforts to be focused on targeting campaign communications to partisan identifiers. Candidates should emphasize their shared party affiliation to these core supporters and should use wedge issues to raise funds or recruit volunteers. In contrast, if candidates are primarily concerned with persuading “swing voters,” we should find that candidates focus on persuasive rather than mobilization appeals. Further, we expect candidates to target campaign communications to Independents and cross-pressured partisans and to use wedge issues in their appeals to persuadable voters rather than core supporters. It is of course a simplification to suppose that any candidate will use a pure strategy of either type, but we can observe which group received more resources and attention, on balance, in direct mail from the 2004 presidential campaign.

Our analysis of campaign strategy primarily looks at direct mail sponsored by either the candidate’s campaign or the political parties (interest group mailings are excluded). There are several reasons to focus attention on direct mail instead of just television advertising. First, both Republicans and Democrats spent unprecedented amounts on the ground-war activities in the 2004 campaign.54 Second, campaign strategy, especially on wedge issues, should be more apparent in the candidates’ “ground war” communications since they are narrowly targeted. In contrast, television commercials will be viewed by partisans and Independents alike, making it difficult to sort out the intended target audience. To be sure, candidates try to target television advertising where possible—in 1984, for instance, Ronald Reagan advertised on 60 Minutes (a “prestige” market), local news, Hill Street Blues (a “high-income male” market), Love Boat (an “older women with high participation rate” market)—but these audiences are still sufficiently heterogeneous to demand broader themes compared to the narrow message possible with direct mail.55 Finally, there already exist several rich studies of television advertising strategy. Two of the most comprehensive studies come from the last two election cycles—Daron Shaw’s, The Race to 270 and The 2000 Presidential Election and the Foundations of Party Politics by Richard Johnston, Michael Hagen, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. These works offer compelling evidence that candidates strategically targeted their television advertising to the most competitive states and media markets. While we offer a cursory analysis of the 2004 candidate strategy through television advertising, we focus our attention on the microtargeted messages sent through direct mail.

In the analysis and discussion that follows, we have omitted campaign communications from interest groups so that we are able to more cleanly outline and test candidates’ motivations. Throughout the book, our focus has been on the relationship between voters and candidates, but this unfortunately minimizes the role and influence of other political actors on campaign dynamics. Interest groups undoubtedly shape campaign discourse, both directly through television advertising or communications with their members and indirectly by pressuring candidates to take positions on their preferred policies. Almost by definition, interest groups will focus their efforts on narrow policy objectives. Thus, the NRA sends gun owners direct mail about the candidates’ positions on gun control policy, and the Sierra Club sends its members messages about environmental policy. It is likely the case, then, that we actually underestimate the extent to which divisive issues were prevalent in the 2004 presidential election.

In focusing on direct mail, we also overlook other means of microtargeting issue messages, since candidates often use telephone calls, personal visits, Web advertising, text messaging, and the like to communicate with narrow audiences. Candidates have long used targeted messages in advertising on African American and Hispanic radio stations, for instance.56 Because radio audiences do not usually overlap, candidates can send issue messages that will generally not be received by other groups. Like direct mail, radio targeting is also difficult to track. As one New York Times journalist reported, “Candidates keep careful track of their opponents’ television advertisements, but just as low-flying planes avoid radar, radio commercials are often able to escape detection.”57 In 1988 Michael Dukakis used radio advertisements to send explicitly contradictory messages on gun control. In television advertisements playing in Texas, the Dukakis message asserted, “[O]ne candidate for President has voted for Federal gun control. Only one. George Bush.” At the same time, radio advertisements playing to predominantly black listening audiences proclaimed, “[I]n George Bush’s Washington, they just say ’no’ to gun control.”58 Private meetings and rallies closed to the press also provide a venue for tailored appeals. For example, in an invitation-only “Family, Faith and Freedom Rally” with Christian evangelicals at the 2004 Republican National Convention, speakers used apocalyptic language to rally the participants on issues like gay marriage, abortion, activist judges, and policy in Israel. According to one account, “The rally struck a very different tone from the speakers behind the lectern inside the Republican convention, where talk of national unity and cultural inclusiveness has been the rule.”59 Although these examples highlight other ways in which candidates are able to microtarget messages, the ability to collect direct mail from a random sample of respondents allows us to concretely evaluate candidate strategies.

Geographical Targeting

We first turn to a cursory comparison of campaign strategy pursued through television advertising compared to direct mail in the 2004 presidential campaign. The first point worth making is that the presidential candidates in 2004 prioritized their direct mail to battleground states, as they did with their other resources and efforts. Reported in table 6.1 are the average campaign efforts in battleground versus non-battleground states. Candidates’ strategies for both direct-mail and television advertising highlight the prioritization that candidates gave to some geographic localities over others. Daron Shaw calculates that candidates spent an average of $8.7 million (14.8 gross point ratings) in the sixteen states that were labeled “battleground” by either of the candidates.60 Although reported at the state level, candidates’ television-advertising strategy is actually conducted at the media-market level.61 Since Bill Clinton, candidates have ranked media markets according to their “cost per persuadable vote” in an effort to more efficiently spend advertising dollars.62 The decision rule of thumb for the Clinton campaign was to “buy ads in markets that had a low price per swing voter. In markets where the price was too high … President Clinton would travel there to exploit the power of the bully pulpit.”63 In his recent account of candidates’ Electoral College strategies, Daron Shaw notes that George Bush used this same strategy, although campaign advisors would sometimes amend it in order to ensure that top-priority states were not missed. Within media markets, television advertising then tends to be concentrated on programs that are more likely to reach a target demographic. For instance, careful analysis of television-viewing data found, somewhat ironically, that Will and Grace was a favorite program of young Republican women, so the campaign aired campaign spots on this gay-friendly program at the same time as they campaigned against gay marriage in direct-mail communications.

Looking at direct mail, we find similar gaps in the amount of campaign material received by individuals living in competitive and non-competitive states—respondents in battleground states received an average of 7.1 pieces of direct mail compared to less than 3 pieces for participants living in safe states. Direct-mail spending is difficult to calculate, but consultants from both sides agree that spending on “ground war” activities had dramatically increased from previous elections. Republican officials estimated that they spent $125 million on “ground war” activities, including a $3.25 million contract with the firm TargetPoint Consulting.64

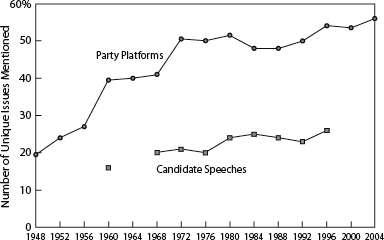

For direct mail, however, candidates take it one step further. Rather than simply targeting individuals living in competitive states, candidates target only those likely to vote. In the CCS data, we find that inactive voters in safe states received less than one direct mail piece on average, compared to more than seven direct-mail pieces received by active voters in battleground states. We see a similar gap in self-reported party contact in the 2004 NES, shown in figure 6.2. Just 14 percent of those not registered to vote reported being contacted by the political parties compared to 68 percent of those registered to vote and living in a battleground state. We can also clearly see this link between information and campaign strategy by looking at errors in the information that candidates have about individual voters. Individuals registered to vote outside the country in which they live (students, individuals who recently moved, snowbirds, etc.) were nearly as unlikely to be contacted as those not registered at all, presumably because candidates lacked the correct contact information. Only 23 percent of these individuals reported being contacted during the campaign. Although nearly 70 percent of these voters indicated that they voted in the election, they were virtually ignored by the political parties.

TABLE 6.1 Campaign Communication by State Competitiveness | |||

Direct Mail Received |

Advertising Dollars (Millions) |

Candidate Visits | |

Battleground States |

7.2 |

8.7 |

11.8 |

Nonbattleground States |

2.9 |

0.0 |

1.2 |

Note: Table shows campaign efforts were concentrated in battleground states. Advertising spending and candidate visits estimated with data provided by Daron Shaw. Mail estimates calculated using 2004 Campaign Communication Study.

Campaign Dialogue on Issues

We turn next to the issue content of direct mail in the 2004 presidential election. Coupled with information about the voters, we have argued that direct mail enables candidates to emphasize more issues and more divisive issues than other forms of political communication. The implication is that candidates often will be talking past each other in the ground-war campaign, even as they might be engaging on broader issues in their television advertising. For instance, recent research has found more than two-thirds of issue attention in presidential campaigns is devoted to the same issues.65 As previously noted, we identified more than seventy-five issues discussed in the direct mail, and have reported the most prominent issues in table 6.2.

The first two columns present the percentage of unique direct-mail pieces containing messages related to a particular policy area. There are several notable findings presented in this table. First, we see that, even in direct mail, the key issues of the campaign—war, the economy, health care, and education—were also featured prominently in the mailings from both candidates.66 Thus, although candidates were indeed discussing more issues through direct mail compared to other forms of campaign communication, in many ways, the mailings were also used to reinforce more general campaign themes. There are, however, notable gaps in issue attention between the Bush and Kerry campaigns, and many of the discrepancies are consistent with the theory of issue ownership. The pro-Bush mail was more likely to emphasize the war on terrorism, while the pro-Kerry mail was more likely to emphasize health care and education. Even more notable in terms of our expectations about wedge issues is the gap in campaign attention on the most divisive political issues. The pro-Kerry mail included mention of the environment, stem cell research, minimum wage, social security, the national debt, and outsourcing, while the pro-Bush mail was much more likely to mention abortion, gay marriage, and tort reform. So, although the campaigns talked about a few of the same major issues of the day, the candidates emphasized different wedge policies.

Figure 6.2: Voter Information and Party Contact in 2004

Note: Figure shows party contact is related to registration status and information. Data source is the 2004 American National Election Study.

TABLE 6.2 Issue Dialogue in 2004 Presidential Campaign Mail | |||

Percentage of Mail Pieces Mentioning Each Issue |

Percentage of Individuals Receiving Mail from Both Candidates | ||

Pro-Kerry Mail |

Pro-Bush Mail |

||

Social Issues |

|||

Environment |

10 |

2 |

2 |

Abortion |

2 |

10 |

2 |

Gay Issues |

1 |

9 |

1 |

Stem Cell Research |

9 |

1 |

0 |

Gun Policy |

1 |

5 |

0 |

Economic Issues |

|||

Taxes |

24 |

29 |

31 |

Health Care |

42 |

13 |

30 |

Education |

27 |

11 |

25 |

Prescription Drugs |

30 |

8 |

24 |

Jobs |

33 |

13 |

23 |

Social Security |

16 |

7 |

14 |

Outsourcing/Trade |

14 |

1 |

9 |

National Debt |

14 |

1 |

0 |

Minimum Wage |

9 |

0 |

0 |

Tort Reform |

0 |

5 |

0 |

Corporate Reform |

5 |

0 |

0 |

Foreign Policy |

|||

Terrorism |

13 |

21 |

30 |

Iraq |

23 |

10 |

28 |

Defense |

9 |

10 |

19 |

Note: Reported in first columns are the percentage of mail pieces mentioning each issue. In last column is the percentage of individuals receiving mail from both candidates calculated for those who received the issue message from either side. Table shows that even when the candidates talked about the same issues, it was rarely to the same individuals. Data source is the 2004 Campaign Communication Study.

The power of the CCS data is that we know who actually received the direct mail, so we can assess whether individuals actually received the same issue messages from one or both candidates. Reported in the final column of table 6.2 is the percentage of respondents who received an issue message from both candidates out of those respondents receiving a piece of mail with the particular issue from either candidate. For example, 31 percent of respondents who received an issue message about taxes received a message from both the Republican and Democratic candidates. What is striking about this comparison is that even though the candidates talked about some of the same issues, they typically talked about them to different individuals.

TABLE 6.3 Wedge-issue Content of Direct Mail and Television Advertising | ||||

Direct Mail |

Television Advertising | |||

Percent General Wedge Issue |

Percent Moral Wedge Issue |

Percent General Wedge Issue |

Percent Moral Wedge Issue | |

Candidate Funded |

30 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

Party Funded |

23 |

7 |

3 |

3 |

Both |

25 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

Note: Table indicates that divisive issues were more prominent in direct mail than television advertising. Direct mail estimates calculated using Campaign Communication Study; television ad estimates provided by Joel Rivlin of Wisconsin Advertising Project based on data from the Campaign Media Analysis Group.

Given the wide range of different issues not covered in table 6.2 above, we created a general wedge issues category that includes all policies on which the candidates took opposing positions about the policy goal (in contrast to opposing positions about the means of accomplishing a shared goal), like abortion, immigration, minimum wage, school prayer, and so on. Capturing three of the most prominent wedge issues of the campaign—abortion, stem cell research, and gay marriage—is our moral wedge issues measure. A full description of our classification is reported in appendix 2.

Comparing the content of television advertising and direct mail allows us to identify message variation based on the message audience. As reported in table 6.3, direct mail was significantly more likely than television advertising to reference a candidate’s position on issues like abortion, stem cell research, and gay marriage. Indeed, there was not a single reference to a wedge issue in any candidate-sponsored ad airing in the 2004 presidential election. There were just a few party-sponsored ads including a reference to one of the wedge issues. Interestingly, the only pro-Bush television advertisements to mention abortion were Spanish-language ads televised on Spanish-language television, itself a rather narrow audience.

This comparison suggests candidates focused on consensual policy issues when communicating with a broad-based audience in television ads, but were willing to make wedge appeals in narrowly targeted campaign messages. If candidates had been purely policy motivated, there would have been less reason to communicate different messages to different audiences, but the evidence suggests that candidates did just this in the 2004 campaign. Clearly, television advertising offers only a limited picture of candidates’ overall campaign policy agendas.

To be sure, candidates continue to spend vast amounts on television advertising—and considerably more than they spend on direct mail and other forms of political communication. And campaigns still do more “macrotargeting” than “microtargeting.” Our key point is simply that these two forms of communication produce very different campaign dialogue, and to the extent that microtargeting continues to grow, scholars must be aware of the potential consequences for campaign dialogue.

Content of Direct Mail

To evaluate whether candidates’ campaign agendas were primarily used to mobilize the base or win over the persuadable voters, we turn to a more detailed analysis of the focus and content of direct mail. Table 6.4 summarizes direct-mail communication, separated by candidate and party sponsorship.

As shown in the first column, almost none of the direct mail could be classified as pure GOTV appeals. Just 5 percent of direct mail funded by the candidates or parties was limited to simply urging the recipient to vote without also suggesting which candidate they should support. Despite the fact that political parties have generally opposed campaign finance restrictions because of the alleged impact on GOTV or party-building efforts, these data make clear that mobilization appeals are almost always accompanied by persuasive appeals.67 It seems clear that there is a blurry line between mobilization and persuasive appeals. Political science research on campaign effects is generally divided between those studying mobilization effects on the one hand and those studying persuasion effects on the other, but the findings here suggest that this may well be a false dichotomy. Candidates rarely, if ever, send out campaign messages that tell people to vote without explicitly telling them who to vote for and why they should vote that way. These findings highlight the disconnect between much of the existing academic research about the campaign “ground war” efforts and actual campaign behavior. Most of the existing research focuses on the mobilizing effect of nonpartisan GOTV campaign messages, but it appears that such messages were rare in the heat of the 2004 presidential contest.68

|

Campaign Appeals in 2004 Presidential Direct Mail | ||||||

Percent Pure Mobilization Appeal |

Percent Volunteer Appeal |

Percent Fund-raising Appeal |

Percent Both Party Labels |

Percent Own Party Label |

Percent Issue Appeal | |

Candidate Funded |

0 |

14 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

70 |

Party Funded |

5 |

4 |

10 |

11 |

50 |

69 |

Both |

5 |

5 |

10 |

10 |

48 |

70 |

Note: Table indicates that direct mail in the 2004 election emphasized issue appeals more than turnout reminders, fundraising or volunteer requests, or partisan appeals. Data source is the 2004 Campaign Communication Study.

Although it is difficult (perhaps even impossible) to distinguish mobilization versus persuasive appeals, we are able to identify whether pieces of direct mail included explicit appeals for money or time. Despite the fact that this is one of the key explanations for why candidates have been polarized in recent years, comparatively few of the 2004 direct-mail campaign pieces included appeals for resources or for volunteer efforts. At least in direct-mail communication, our findings suggest that candidates were primarily concerned with raising money or soliciting volunteers, as we might expect if the party-activist hypothesis was correct. The lack of fund-raising and volunteer appeals is especially notable because for many decades political direct mail was primarily a tool for political fund-raising. Today, however, candidates have information about nearly every voter, not just the activists, so direct mail is more commonly used as an alternate form of political communication and advertising.

Perhaps more telling of candidate strategy is the fact that just 9 percent of candidate-sponsored direct-mail pieces mentioned the candidate’s political party, and just half of the pieces sponsored specifically by the political party did so. Despite some expectations that candidates would try to activate the partisan base by reinforcing and highlighting partisan attachments, the majority of mail advertising did not mention a candidate’s party affiliation. Although candidates may very well have been trying to activate their partisan base by motivating them with an issue appeal, they were not simply reminding their supporters of their partisan identities. Yet the vast majority (70 percent) of direct-mail pieces included issue-based appeals. Looking at the overlap of partisan and issue content highlights even further that partisan activation did not appear to be the foremost motivation of the direct mail. We find that mail omitting the party affiliation of the favored candidate included an average of 5.2 issue positions compared to just 2.4 positions in the mail that included the candidate’s party affiliation. Moreover, mail without party labels was twice as likely to mention a wedge issue (34 percent versus 16 percent) and three times as likely to mention a moral issue (4 percent versus 12 percent).69 If candidates were following a coalitional strategy in which they were using issues to appeal across party lines to those who might be amenable on the issue, we would expect just this pattern—candidates downplaying their party attachments and highlighting issues in an effort to make the issue salient in the minds of persuadable voters. As one Bush advisor explained, core supporters were not ignored; they just received fewer “touches” than swing voters.70

Recipients of Direct Mail

Examining who actually receives direct-mail advertising also helps clarify what strategies candidates were pursuing. We again focus not only on the amount of mail received, but also on the content. Table 6.5 reports the percentage of mail pieces received containing divisive issue appeals received by Democrats, Republicans, and Independents.71 We look not only at the “moral wedge issues” and “general wedge issues” classifications previously used, but also at a category we call “targeted issues.” This final category is an even more encompassing classification including any policy area of concern to a particular voting constituency—these include all moral and general wedge issues as well as issue topics such as senior health care, agricultural issues, and local issues. The specific issues included are listed in appendix 2. As reported in table 6.5, we see that political Independents received more mail on average and were more likely to receive advertising with targeted, wedge, and moral issue appeals. This finding is notable because the expectation of a base mobilization strategy would be that partisans should have been more likely than Independents to receive direct mail about divisive issues. And it stands in contrast to research concluding that core party supporters are more likely to be targeted with campaign information.72 This table also highlights that candidates are often going after the same voters, even if they are targeting them with different messages. At the same time that candidates try to peel away voters from the opposition coalition, they are also attempting to hold on to their own cross-pressured partisans.

Unfortunately, the CCS survey does not include questions about an individual’s policy preferences, so we are unable to precisely identify cross-pressured partisans as we have in previous chapters. Although it is a less ideal measure, the American National Election Study asks respondents if they were contacted by each of the political parties. Using our earlier measure of cross-pressured partisans, we found that 53 percent of cross-pressured partisans reported being contacted by the opposing party in the 2004 presidential election, compared to just 29 percent of consistent partisans.73 This gap in contact rates suggests that candidates are concentrating their efforts on the individuals who are most likely to be responsive.

|

Direct Mail Received by Partisan Identification | |||||

All Presidential Mail |

Party & Candidate Mail |

Percent Received Moral Appeal |

Percent Received Wedge Appeal |

Percent Received Targeted Appeal | |

Democrat |

6.4 |

3.2 |

19 |

29 |

36 |

Independent |

8.5 |

5.5 |

24 |

32 |

41 |

Republican |

6.5 |

4.6 |

18 |

31 |

39 |

Note: Table indicates that Independents received more mail on average than partisans, and mail received was more likely to contain divisive issue content. Data source is the 2004 Campaign Communication Study.

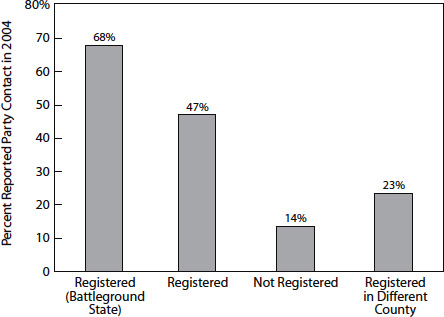

Although we cannot precisely distinguish between the persuadable partisans and the consistent core supporters in the CCS survey, we can use strength of party identification as a proxy. Although a blunt classification, particularly given our findings in chapter 2 showing that cross-pressures exist even among strong partisans, this proxy allows us to compare the content of direct mail received by core supporters (strong partisans) to that received by persuadable voters (weak partisans and Independents). Are we more likely to find wedge appeals used in mail received by the partisan base or in the mail received by persuadable voters? Figure 6.3 reports the percentage of pro-Kerry and pro-Bush mail containing wedge, moral, or targeted appeals received by strong Democrats, weak/leaning Democrats, Independents, weak/leaning Republicans, and strong Republicans.

Despite the conventional wisdom that the 2004 presidential candidates used divisive issues to mobilize and motivate their base, we find compelling evidence that mail sent to persuadable voters was more likely to contain wedge issues than that received by the partisan base. Wedge, moral, or targeted appeals were actually less prevalent in the direct mail received by a candidate’s own strong partisans. Looking at each type of wedge appeal, we find a nonmonotonic relationship over the partisan scale, with a candidate’s own base supporters and his opponent’s base supporters receiving the lowest percentage of direct-mail advertising with divisive content. Persuadable voters—Independents and weak partisans—received the highest percentage of divisive-issue content. For instance, roughly 8 percent of pro-Bush direct-mail pieces received by strong Republicans included messages about abortion, homosexuality, or stem cell research, compared to 11 percent of pro-Bush ads received by Independents, and 16 percent of those received by weak Democrats. Similarly, 40 percent of pro-Kerry ads received by strong Democrats included targeted issues, compared to 44 percent of pro-Kerry ads received by weak Democrats, 61 percent received by Independents, and 63 percent received by weak Republicans. Put simply, if a candidate sent a message to someone from the other side in the 2004 election, the campaign appeal was quite likely to give the recipient an explicit policy reason to abandon her affiliated party.

Figure 6.3: Targeted Issues as a Percentage of Mail Received

Note: Graph indicates that direct-mail advertising sent to weak partisans and Independents was more likely to contain divisive issue content than direct-mail advertising sent to a candidate’s own strong partisans. Data source is the 2004 Campaign Communication Survey.

Figure 6.3 does hint at an interesting difference between the two political parties. It appears that both campaigns were more likely to use wedge appeals to target wavering Democrats than wavering Republicans. In other words, the Bush campaign appeared more likely to engage in an offensive strategy—looking to pick off Democrats who agreed with the president on some divisive issues—while the Kerry campaign appeared to be more defensive in their strategy—attempting to hang on to wavering Democrats. It appears that Kerry was using divisive issues to “microshield” his own cross-pressured partisans. This pattern may also be consistent with common interpretations in the media and among pundits that the Republicans did a better job of taking advantage of the information databases to target campaign messages. According to one journalistic account, “Both parties engaged in this microtargeting. … But strategists on both sides agreed that the depth of the Republican files grew far greater, included more information, and were put to smarter use in the field, thus increasing the data’s predictive power.”74

Overall, our analysis here suggests that candidates do not use wedge issues solely, or even primarily, to motivate their base. Media accounts following the 2004 presidential election seemed to have interpreted the candidates’ focus on divisive issues as evidence that candidates were engaging in a base mobilization strategy, but this interpretation appears incomplete. Consultants and party leaders, in contrast, were more likely to acknowledge that the campaigns were also focused on winning Independents and opposing partisans. Bush’s campaign manager, Ken Mehlman, explained, “The press, unfortunately for them, believes that it’s zero-sum, that it’s either a base or a swing strategy. And the fact is, we appeal to both.”

Why did the media get it wrong? In part, it may be an issue of semantics. When Republican advisors talked about “expanding the base,” they were indicating that they were appealing to Independents and Democrats who agreed with Bush on a particular policy dimension. Brent Seaborn, vice president of TargetPoint Consulting, explained:

We wanted to most effectively allocate the resources we have. Some of those resources need to go to mobilization, some of them need to go to persuasion. That was all built around this idea that Rove always talked about mobilizing and expanding the base. Most people tended to focus on that mobilizing the base as [sic] what the campaign was supposed to be about. But there was also this very heavy element on expanding the base and finding what these people had in common with the president already and treating them as if they were in the base. Traditionally we would ignore these people because they don’t have an R next to their name. But being able to say, “These people might have a D or an I next to their name, but there are three issues that [they] are right with the president on.” This wasn’t about going out and persuading people, “You don’t agree with the president on any issues, but you should vote for him anyway.“75

More importantly, the persuadable voters were not viewed as a homogeneous group of unsophisticated, ideologically moderate, political Independents who would make up their minds based on candidate personality and charisma. Instead, candidates looked for persuadable voters who might be receptive on an issue about which they disagreed with their own party’s nominee. Bush strategist Matthew Dowd explained that the campaign made the assumption that “voters are smart. They’re not dumb. They can’t be spun. We can’t put up a television spot to convince them of something that they don’t believe. … We assumed voters were able to take information, factor it in, factor it out, and come to the conclusion in a very smart, intelligent way.”76

In today’s political context in which the elections are razor close and the political parties are more evenly divided than ever before, candidates look for every possible angle that might make a difference in the election outcome. The candidates did not try to change the policy preferences of voters; rather, they tried to raise the salience of a policy preference that was consistent with the preferences of their partisan base. Consultant Hal Malchow explained,” Once I can get them on that one issue, then I can get them to take action and get them to be involved politically and ideologically. … You don’t have to change 50 percent of Americans, you don’t have to change 30 percent. You move 2 percent or 3 percent in New Mexico or Missouri or Wisconsin on one issue, then you’ve done a whole lot.”77 With detailed information about the preferences of the electorate, candidates look for any possible issue—no matter how small or inconsequential to others in the electorate—that could be exploited for electoral gain.

Implications of Campaign Strategy for Political Inequality

What are the implications of this persuadable-voter strategy? On the one hand, some might view these findings in a positive light. After all, candidates are not simply catering to their base supporters and ignoring the general electorate as some have decried. It has been argued that a base mobilization strategy has either contributed to or resulted from the polarization in the electorate and holds detrimental consequences for American democracy. Political reporter Thomas Edsall argues that a “collapse of the middle” has allowed President Bush to “discard centrist strategies” and to promote “polarizing policies designed explicitly to appeal to the conservative Republican core.”78 The tactic of microtargeting has been credited with engaging people because it connects with them on their interests. Political scientist David Dulio argues that microtargeting should be good for democracy because it at least “focuses attention on the issues that are important to voters … [and] strengthens debate between two candidates.”79 Consultant Alex Gage similarly concluded that “from an institutional standpoint we think it’s beneficial. It’s going to the voter, and indeed talking to them about what is important to them.”80

Our analysis provides evidence that candidates focus on swing voters, but the findings are hardly reassuring from a normative standpoint. In today’s hyperinformation environment, the campaign tactics for winning over persuadable voters have changed, with potentially negative consequences. In the conclusion of this book, we consider in more detail the potential implications of microtargeting for democratic accountability and governance. For now, we point out the clearly observable implications that these campaign tactics have for political inequality.

As candidates become more efficient in targeting their resources, some people in the electorate are increasingly marginalized and ignored. Republican consultant David Hill explained, “There is a practical reason that we don’t focus on those unlikely to vote. … [It] comes down to a budgeting issue.”81 With the explosion in the amount, type, and quality of information about individual voters, candidates can more efficiently allocate their political and financial resources, exacerbating political inequalities in party contact. More than ever before, presidential candidates can now ignore large portions of the public—nonvoters, those committed to the opposition, and those living in uncompetitive states. The preferences of these individuals are not unknown, rather they are deliberately disregarded.

Scholars have long been concerned about inequalities in party contact, primarily because it is thought to be an important determinant of political participation, and participation, in turn, is consequential for the policies that our representatives pursue.82 Sidney Verba, Kay Schlozman, and Henry Brady argue that “[d]emocracy rests on the notion of the equal worth of each citizen. The needs and preferences of no individual should rank higher than those of any other. This principle undergirds the concept of one person one vote as well as its corollary, equality of political voice among individuals.”83 Our work extends this important political inequality literature by suggesting that microtargeting influences the policy promises that candidates make even before they are elected. In today’s information environment, candidates are surgically targeting issue appeals to persuadable voters, while ignoring those individuals inconsequential to a winning coalition. In a recent study, Markus Prior attributed changes in the composition of the electorate over time to changes in voluntary media consumption—in today’s media environment those not interested in politics can avoid it altogether.84 To this explanation, we would add that the candidates’ decision to ignore these citizens also shapes their involvement in the political process. Candidates today more precisely target their campaign efforts to those individuals likely to vote thereby reinforcing and exacerbating the participation gap between those politically unengaged and those politically engaged. There is a perverse trend that increasing information about the American public makes it less likely that our political system offers equal representation for all citizens. As it becomes easier to differentiate the less politically motivated from the engaged citizens in the electorate, it becomes less likely that the views of the former are reflected in election outcomes.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we examined the implications of our arguments for candidate strategy and behavior. Because persuadable voters can be won over if a policy cross-pressure is activated, candidates have an incentive to prime wedge issues in their campaign appeals. Given the complexity and diversity of voter belief systems—and a data-rich information environment that has informed the candidates of those belief systems—candidates attempt to microtarget different campaign messages to different persuadable voters. One consequence of this campaign strategy is that candidates are taking positions on more issues, and more divisive issues, than ever before.

Although our data help explain how the information environment today provides the conditions for divergent policy platforms, we must acknowledge the limits of our analysis. There are a great number of issues—many of which may be the most important to voter decision making—on which the candidates still have an incentive to take a centrist opinion. On the issues that most voters believe are pressing—typically consensual issues like education and health care—candidates will likely take widely supported policy positions. Nearly every candidate promises to be the “education” president. For example, referring to George W. Bush’s campaign strategy in 2000, Mark McKinnon, director of media for the Bush campaign, explained their strategy on important consensual domestic issues,